This blog was co-authored by Martin Lee and Jaeson Schultz with contributions from Warren Mercer.

The recent discovery of Wekby and Point of Sale malware using DNS requests as a command and control channel highlights the need to consider DNS as a potentially malicious channel. Although a skilled analyst may be able to quickly spot unusual activity because they are familiar with their organisation’s normal DNS activity, manually reviewing DNS logs is typically time consuming and tedious. In an environment where it might be unclear what malicious DNS traffic looks like, how can we identify malicious DNS requests?

We all have subconscious mental models that shape our perceptions of the environment and help us to identify the unusual. An outlandish or unusual happening in the local neighbourhood piques our curiosity and make us want to find out what is going on. We compare our expectations of normality with our observations, if the two don’t match we want to know why. A similar approach can be applied to DNS logs. If we can construct a baseline or model of ‘normality’ we can compare our observations to the model and spot if reality as we see it, is wildly different from that which we would expect.

We are familiar with common DNS requests such as requesting the IP address of ‘www.cisco.com’, but what kind of request would be so unusual as to require investigation? Malware could encode stolen data as the subdomain part of a DNS lookup for a domain where the nameserver is under control of an attacker. A DNS lookup for ‘long-string-of-exfiltrated-data.example.com’ would be forwarded to the nameserver of example.com, which would record ‘long-string-of-exfiltrated-data’ and reply back to the malware with a coded response.

Naively, we would expect the subdomain part of such requests to be much longer than usual requests. We can use the distribution of the lengths of subdomains within DNS requests to construct a mathematical model that describes normality, and use this to compare our observations to identify the outlandish.

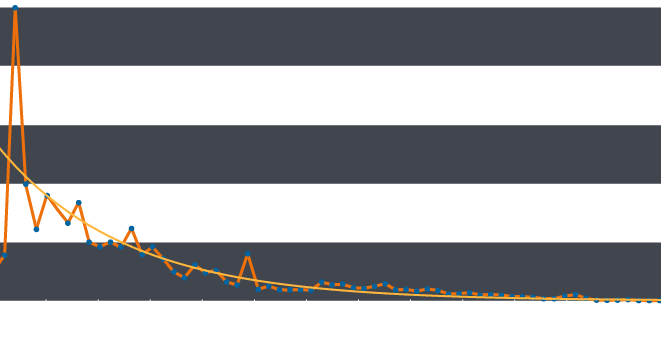

Calculating the frequency of occurrence of subdomain length by removing the domain name and domain extension of a sample of DNS requests gives the following graph:

The orange line shows the distribution of subdomain lengths from single up to sixty five characters. Although it is obviously not an exact fit, this distribution approximates to the smooth exponential curve shown in yellow. We can use this curve as our model of normality and compare our observed values to this curve in order to spot anomalies.

Immediately we can see that subdomains of three characters in length are far more common than we would expect. Understandably, this corresponds to the length ‘www’, a very common subdomain string. To measure how more frequent this observation is than we would expect, we can divide the observed value by that predicted from our curve in order to calculate a metric of how unusual this observation is.

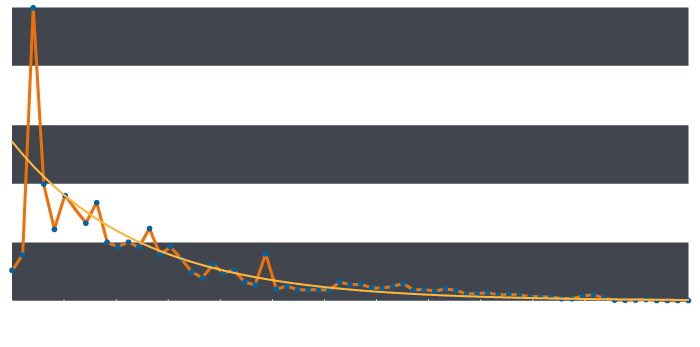

Continuing this calculation for all the length values and plotting this gives a graph showing how much reality diverges from our expectations of normality for each subdomain length:

Clearly, a handful of subdomain lengths are occurring at much higher frequencies than we would expect. Indeed, so great is the divergence from that expected that a few values had to be truncated at 1000.

Concentrating on these outlandish values reduces the manual work necessary to review the set of logs. Many of these particularly long subdomains turn out to be legitimate cloud services or content distribution networks. However, a handful of domains with subdomains of 231 and 233 characters in length seemed particularly interesting.

log.nu6timjqgq4dimbuhe.3ikfsb---redacted---cg3.7s3bnxqmavqy7sec.dojfgj.com

log.nu6timjqgq4dimbuhe.otlz5y---redacted---ivc.v55pgwcschs3cbee.dojfgj.com

lll.nu6toobygq3dsnjrgm.snksjg---redacted---dth.ejitjtk4g4lwvbos.amouc.com

lll.nu6timrshe4timrxhe4a.7vmq---redacted---hit.w6nwon3hnifbe4hy.amouc.com

ooo.nu6tcnbug4ytkobxhe4q.zrk2---redacted---hxw.tdl2jg64pl5roeek.beevish.com

ooo.nu6tgnzvgm2tmmbzgq4a.rkgo---redacted---tw5.5z5i6fjnugmxfowy.beevish.com

Despite the name server for each domain being hosted on different networks, the domains share a number of unusual features. There are hundreds of subdomains for each domain, but each unique subdomain is only ever accessed once. Although, not necessarily uncommon, each DNS lookup resulted in ‘192.168.0.1’ being returned.

Dojfgj.com is a known malicious domain by which the Multigrain malware exfiltrates stolen credit card numbers. The clear similarities between the three domains suggest that the previously unknown amouc.com and beevish.com domains are related to that of dojfgj.com.

The Multigrain malware uses base32 encoding to exfiltrate data from infected machines. Although less space efficient than the more commonly known base64 encoding technique, base32 encoding uses an alphabet consisting of the characters a-z and the digits 2-7. The digits '0' and '1' are omitted from the base32 alphabet due to their similarity to the letters 'O' and 'I'. The encoding has the advantage that there are no characters which cannot be used in a DNS lookup, and that capitalisation does not need to be maintained.

The major part of the multigrain DNS request is encrypted, but the first section encoding an identifier of the infected machine is readable. For example, the section beginning nu6t in the following:

ooo.nu6tgnzvgm2tmmbzgq4a.rkgo---redacted---tw5.5z5i6fjnugmxfowy.beevish.comdecodes to: m=3753560948

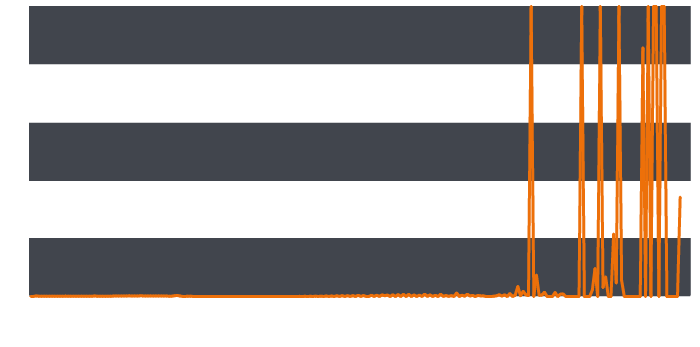

Any feature of DNS requests such as the length of the domain name, the number of subdomains etc. can all be used to construct models of expected behaviour to which observed values can be compared.

These identify domains with similar patterns such as:

4-9-8-2-2-3-8-5-4-6-2-9-2-3-8-8---redacted---7-.0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-49-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0.info

5-2-4-6-3-2-2-7-4-8-3-6-7-1-2-3---redacted---0-.0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-49-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0.info

6-t-y-s-8-l-l-p-6-6-x-q-2-l-2-9-x-7---redacted---a-.0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-45-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0.info

7-8-5-4-1-2-7-2-7-8-4-5-1-5-0-7---redacted---0-.0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-28-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0-0.infowhich are known to be associated with the W32/AutoRun worm. And the hilarious:

77newyourcomputerhaveaseriousproblemcallon18883142770tollfree.yourcomputerhaveaseriousproblempleasecallon18883142770tollfree.yourcomputerhaveaseriousproblempleasecallon18883142770.windows-has-detected-some-suspicious-activity-fromyourcomputer.comassociated with phishing scams.

Monitoring logs, and DNS logs in particular, is an excellent technique for spotting attacks. When you have more data than you can eyeball, using simple techniques to model the data can help identify those entries that require a second glance. Its these second glances that often make the difference between well defended and compromised networks.