Note: The blog post is part 3 of 3. The first two blog posts can be found:

Decoding Domain Generation Algorithms (DGAs): Part I

Decoding Domain Generation Algorithms (DGAs) Part II - Catching ZeusBot Injection into Explorer.exe

At this point, you can go ahead and close the two parent processes (since we are not interested in their functionality, for the sake of simply finding the DGA). So we know that we are interested in discovering how this traffic is generated. So let’s try to find out where it originates.

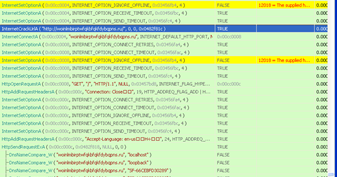

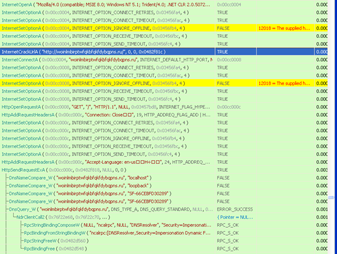

Earlier, using API Monitor, we saw that explorer was using several functions within WinINet.dll:

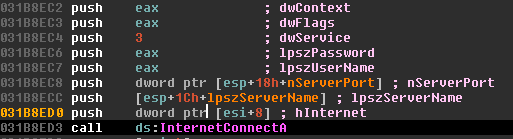

So let’s set a breakpoint (F2) on a function that deals with Internet traffic in WinINet.dll. For example, InternetConnect():

HINTERNET InternetConnect(

_In_HINTERNET hInternet,

_In_LPCTSTR lpszServerName,

_In_INTERNET_PORT nServerPort,

_In_LPCTSTR lpszUsername,

_In_LPCTSTR lpszPassword,

_In_DWORD dwService,

_In_DWORD dwFlags,

_In_DWORD_PTR dwContext

);

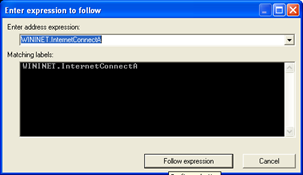

Hit ctrl+g to get this handy search window. Then type InternetConnectA (A for ANSI as opposed to Wide) to find the matching function and its address:

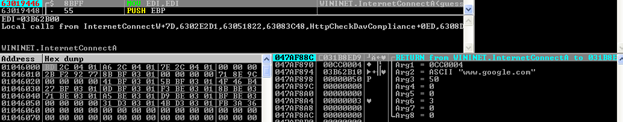

Click "Follow expression" and breakpoint, hit play and see what happens in Wireshark until your breakpoint is hit.

We see several attempts to send UDP traffic (again, outside of the scope of this post), but just wait about 45 seconds until you hit your breakpoint. It looks like it is querying Google. This is a common thing for malware to do in order to test connectivity before functioning.

Hit CTRL+F9 to return to the caller in our main executable.

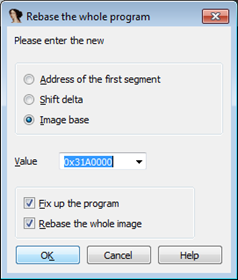

Look at this address in IDA to figure out what’s going on around this function. Also you may want to rebase your program in IDA to the offset injected into Explorer:

Note that this offset will be different each time this program is injected. Let’s examine the calling function address to see what’s going on.

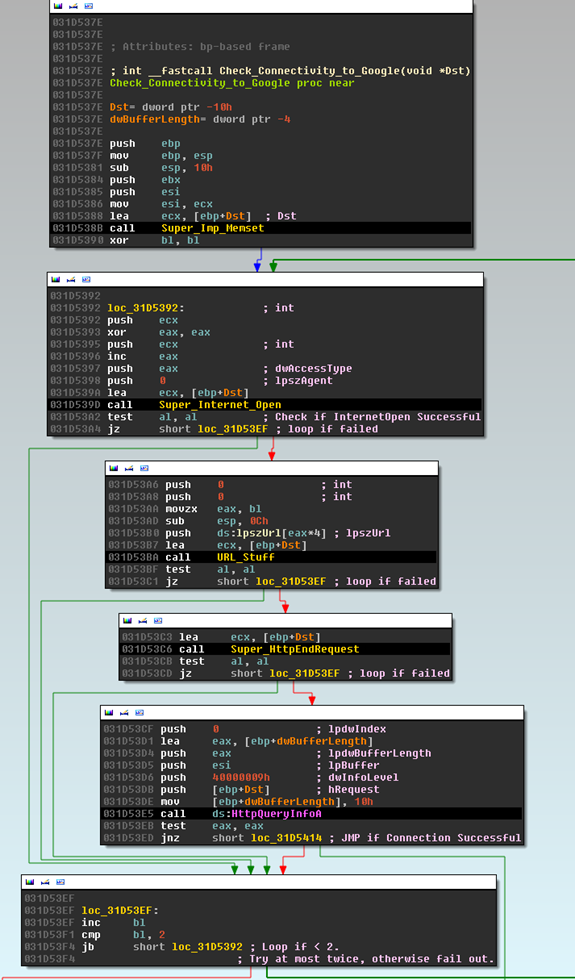

In order to see what called this function, hit ‘x’ on the function name to bring up a list of callers. Hit Enter on the first function and again on this function. I am doing this for the sake of some brevity, but this segment really just calls InternetConnect() and the HttpOpenandSendRequest() function, so move on up to the caller. I named this function Check_Connectivity_to_Google because that’s exactly what it does (Note: I’ve also seen it query Bing.com, the whole point is that it is a connectivity check). It actually will try twice before failing out:

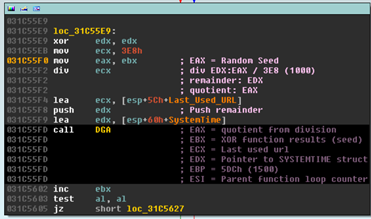

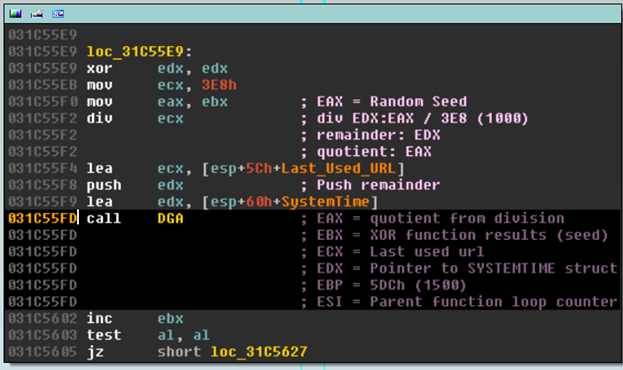

Following that function, another function that is immediately following references a SystemTime structure, this is indicative of a DGA function. It actually is our DGA function, hence the name I gave it (DGA in Yellow below):

I annotated the register values and some instructions above the call to help shorten the post. Note the push of a value I named “remainder”. This value is very important and it is used throughout the DGA function. Let’s go ahead and see how that value is generated.

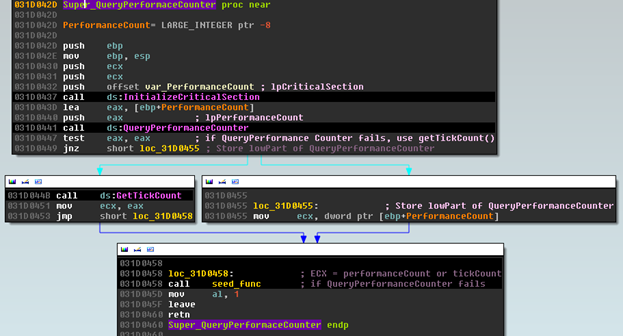

The instruction ‘div’ (executes EDX:EAX/ECX. EAX) in this function is “randomly” generated by a function that uses QueryPerformanceCounter() or GetTickCount() as a value passed to a function that performs a few shift and xor calls of its own:

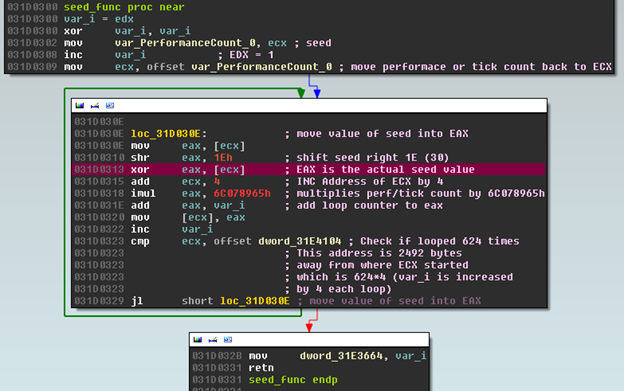

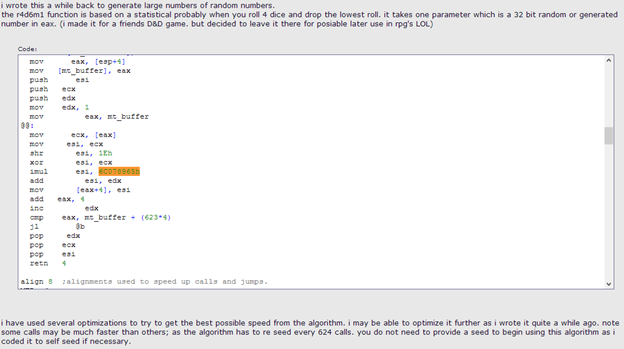

Interestingly enough, if we Google the hex value 6C078965h, we come across a post where someone describes a “random” number generator they wrote that is very similar (just different registers) to this function, used to generate dice rolls for a DND game. (Notice in the loop above how var_PerformanceCount is at 31E3748. The DWORD 31E4104 is used as a maximum value for the loop counter. It is exactly 9BCh or 2492 (623*4) bytes off). Which aligns with this post as well:

I also see similar algorithms used for various other functionalities in other programs. Just Google it if you are curious.

public static functioninitializeRandGenerator(seed:uint):void{

//the seed can be any positive integer

MT = newArray();

indexMT = 624;

MT[0] = seed;

var i:int;

for(i = 1; i < 624;i++){

MT[i] = uint(0xFFFFFFFF &(0x6C078965 *(MT[i-1] ^(MT[i-1] >>>30)) +i));

}

}

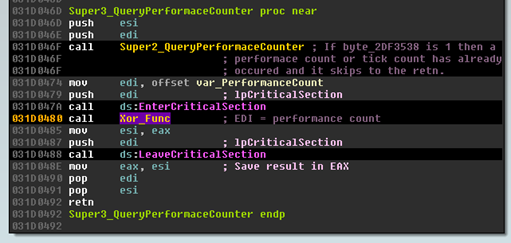

Either way, that value is reasonably unpredictable if you aren’t on the machine that is generating the number. This value is then sent through an XOR function:

In which the result is divided by 1000 (or mod 1000, eventually meaning 1000 possible seed values) and stored in EDX as we call the main DGA function:

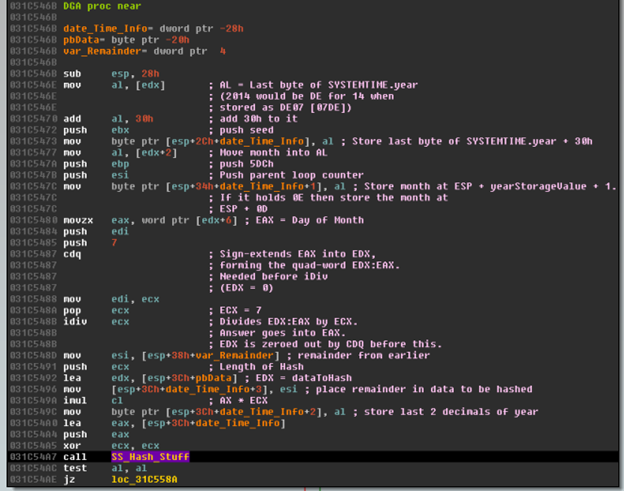

There are two parts to this DGA, one where the domain name is generated and another where the Top Level Domain or TLD (for short) is generated. Before any of this occurs though, 7 bytes of data are generated to be passed to an MD5 function. The division by 1000 earlier is really just mod 1000, leaving 1000 possible domains.

These 7 bytes are stored as follows:

Last byte of year + 30h | Month | Day/7 *7 | First Random Byte | Second Random Byte | 00 | 00 |

For Example:

byte_array[]{0x0E,0x01,0x0E,0xAC,0x00,0x00,0x00};

First_Byte: Last Byte of year +30h

2014=07DE-> DE +30h=0E

Second_Byte: Month

January =01

Third_Byte:( Day / 7)*7

([17 / 7]*7=14->0E)

Fourth_Byte and Fifth_Byte: “Random” seed (0-1000) that is incremented by one

The low byte value is used for the TLD as well

Sixth_Byte and Seventh_Byte:0000 C Version:

int genDate(unsignedchar*dateData){

unsignedchar year;

unsignedchar month;

unsignedchar day;

time_t currTime = time(NULL);

struct tm *localTime;

localTime = localtime(&currTime);

year =((localTime->tm_year +1900)&0xff)+0x30;// Add 30h to last byte of year

month = localTime->tm_mon +1;// Just plain month - Number of months since January + 1

day =(localTime->tm_mday /7)*7;

unsignedchar combined[]={ year, month, day };

memcpy(dateData,&combined,4);

return1;

}

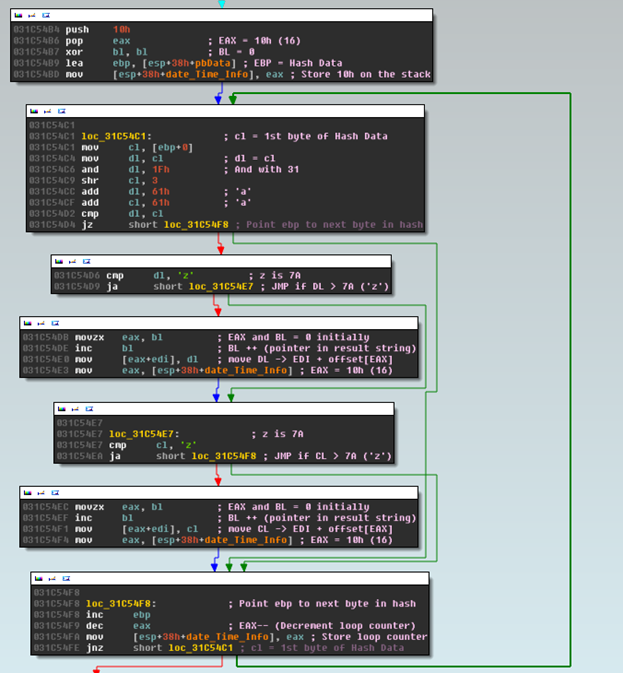

That data is then sent to an MD5 function at 0x31C54A7. That result is used to generate the domain name and the lower byte of the random number is used to generate the TLD:

I have annotated the instructions and written it in C:

#define HASHLEN 16

int genURL(unsignedchar*hashValue,char*URL){

// Grab each byte of hash

unsignedint j;

unsignedint currentIndex =0;// Pointer to current index in URL array

for(j =0; j < HASHLEN ; j++){

unsignedchar cl = hashValue[j];

unsignedchar dl = cl;

dl =(dl &0x1F)+0x61;

cl =(cl >>3)+0x61;

if(cl != dl){

if(dl <=0x7A){

URL[currentIndex]= dl;

currentIndex++;

}

if(cl <=0x7A){

URL[currentIndex]= cl;

currentIndex++;

}

}

}

return1;

}

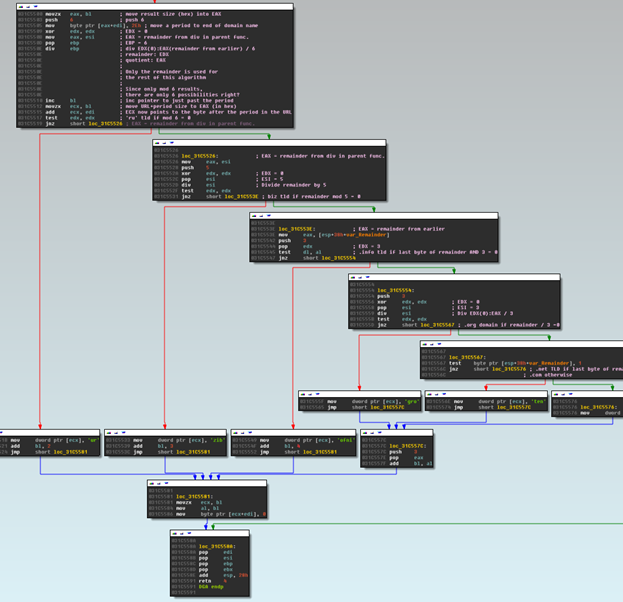

So now that we have the domain name, it’s time to grab the TLD, if we look just below the domain-name code, we can see the TLD-generation section. It is really simple actually, it just checks if the last byte of the random number against a few math functions. Depending on the result, we get one of six possible TLDs. Note the “shape” of the the overall function, this is usually indicative of a case statement or if/then sections:

C Version:

int genTLD (unsignedshort rand,char*TLD){

unsignedchar lobyte =(rand &0xff);

if((rand %6)==0){

strncpy(TLD,".ru",4);

}

elseif((rand %5)==0){

strncpy(TLD,".biz",5);

}

elseif((lobyte &3)==00){

strncpy(TLD,".info",6);

}

elseif((rand %3)==0){

strncpy(TLD,".org",5);

}

elseif((lobyte &1)==0){

strncpy(TLD,".net",5);

}

else{

strncpy(TLD,".com",5);

}

return1;

}

All of this is done over and over again, generating 1000 possible domains. That “random” seed value is really just a starting point and all of the URLs are called eventually at a rate of just about 1 per second.

Putting it all together

After figuring out how this DGA is assembled, it is clear that it only changes once every 7 days or the beginning of a new year or month. There are still 1000 possible URLs over this period since two bytes are unknown and incremented/used one-by-one. That’s not bad if you are the attacker. If we do the math at just 1 domain per second, it takes roughly 16 minutes to call each domain. This means that the attacker needs to generate a list of 1000 domains for a particular day and pick one, then the attacker has to wait at most 17 minutes for a call out back to his/her server. Not bad.

In the end, a list can be generated in C for any date we want pretty easily:

/*

gcc -Wall dga.c -o dga -lcrypto -lssl

Use without args for todays date.

To generate domains for another date, simply run with:

./dga mmddyyyy

*/

#include <stdio.h>

#include <stdlib.h>

#include <time.h>

#include <string.h>

#include <openssl/md5.h>

#define HASHLEN 16

int GetMD5Hash (unsignedchar*pbData,int size,unsignedchar*hashValue);

int genURL (unsignedchar*hashValue,char*URL);

int genTLD (unsignedshort rand,char*TLD);

int genDate(unsignedchar*dateData);

intgenSuppliedDate(char*argv[],unsignedchar*dateData){

int year;

unsignedchar month;

unsignedchar day;

longint a =strtol(argv[1],NULL,10);// grab int without atoi

month = a /1000000;

day = a /10000%100;

year = a %10000;

year =(year &0xff)+0x30;// Add 30h to last byte of year

day =(day /7)*7;

unsignedchar combined[]={ year, month, day };

memcpy(dateData,&combined,4);

return1;

}

intgenDate(unsignedchar*dateData){

unsignedchar year;

unsignedchar month;

unsignedchar day;

time_t currTime = time(NULL);

struct tm *localTime;

localTime = localtime(&currTime);

year =((localTime->tm_year +1900)&0xff)+0x30;// Add 30h to last byte of year

month = localTime->tm_mon +1;// Just plain ol' month - Number of months since January + 1

day =(localTime->tm_mday /7)*7;

unsignedchar combined[]={ year, month, day };

memcpy(dateData,&combined,4);

return1;

}

// Generate TLD based on random seed based on low-byte

// of random seed

int genTLD (unsignedshort rand,char*TLD){

unsignedchar lobyte =(rand &0xff);

if((rand %6)==0){

strncpy(TLD,".ru",4);

}

elseif((rand %5)==0){

strncpy(TLD,".biz",5);

}

elseif((lobyte &3)==00){

strncpy(TLD,".info",6);

}

elseif((rand %3)==0){

strncpy(TLD,".org",5);

}

elseif((lobyte &1)==0){

strncpy(TLD,".net",5);

}

else{

strncpy(TLD,".com",5);

}

return1;

}

// Generate URL based on MD5 hash

int genURL(unsignedchar*hashValue,char*URL){

// Grab each byte of hash

unsignedint j;

unsignedint currentIndex =0;// Pointer to current index in URL array

for(j =0; j < HASHLEN ; j++){

unsignedchar cl = hashValue[j];

unsignedchar dl = cl;

dl =(dl &0x1F)+0x61;

cl =(cl >>3)+0x61;

if(cl != dl){

if(dl <=0x7A){

URL[currentIndex]= dl;

currentIndex++;

}

if(cl <=0x7A){

URL[currentIndex]= cl;

currentIndex++;

}

}

}

return1;

}

//Compute the MD5 checksum for generated bytes

intGetMD5Hash(unsignedchar*pbData,int size,unsignedchar*hashValue){

unsignedchar digest[HASHLEN];

MD5_CTX ctx;

MD5_Init(&ctx);

MD5_Update(&ctx, pbData,7);

MD5_Final(digest,&ctx);

memcpy(hashValue, digest, HASHLEN);

return1;

}

int main(int argc,char*argv[])

{

unsignedchar dateData[3];// Store Date data after modification

char URL[33]={};// Store resulting generated URL, 32 bytes is max possible length + \0

char TLD[6];// Store generated TLD

if( argc ==2){

if(!(genSuppliedDate(argv, dateData))){

return0;// if the date fails, error out

}

}

// Generate first 3 bytes for hash

elseif(!(genDate(dateData))){// if the date fails, error out

printf("Failed to generate date hash data, exiting");

return0;

// Failure

}

unsignedshort i;

for(i =0; i <1000; i++){// need to +1 because it ranges from 0000-1000

unsignedchar hashValue[HASHLEN];// MD5 Hash of given bytes

memset(URL,0,sizeof(URL));// clear arrays

memset(TLD,0,sizeof(TLD));// clear arrays

// Reverse order of bytes when generating URLs,

// This will match the order in how it URLs are

// incremented in the malware itself

unsignedchar hibyte =(i >>8)&0xff;

unsignedchar lobyte =(i &0xff);

// unsigned short combined = lobyte << 8 | hibyte;

unsignedchar pbData[7]={ dateData[0], dateData[1], dateData[2], lobyte, hibyte,0x00,0x00};// Given Bytes

if(GetMD5Hash(pbData,sizeof(pbData), hashValue)){// If MD5 Successful

if(genURL(hashValue, URL)){

unsignedshort k;

// Print URL

for(k =0; k <strlen(URL); k++){

printf("%c", URL[k]);

}

if(genTLD(i, TLD)){// random value (Before flipping it around for the hash)

// Print TLD

for(k =0; k <strlen(TLD); k++){

printf("%c", TLD[k]);

}

printf("\n");

}

}

}

}// count loop

return0;

}