This post was written by Martin Lee and Vanja Svajcer.

2017 was an eventful year for cyber security with high profile vulnerabilities that allowed self-replicating worm attacks such as WannaCry and BadRabbit to impact organizations throughout the world. In 2017, Talos researchers discovered many new attacks including backdoors in legitimate software such as CCleaner, designed to target high tech companies as well as M.E.Doc, responsible for initial spread of Nyetya. Despite all those, headline making attacks are only a small part of the day to day protection provided by security systems.

In this post we review some of the findings created by investigating the most frequently triggered Snort rules as reported by Cisco Meraki systems and included in the Snort default policy set.

Top 5 Rules

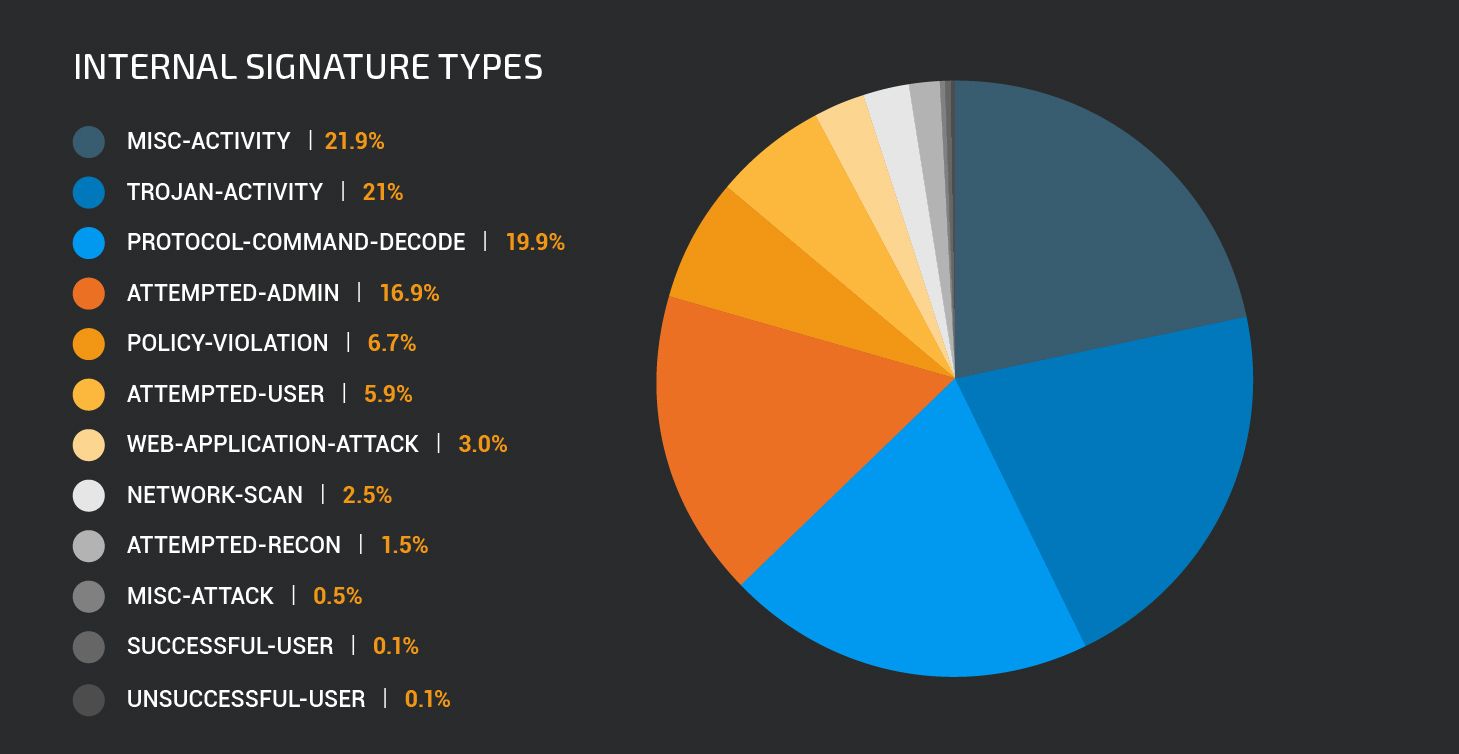

Snort rules are classified into different classes based on the type of activity detected with the most commonly reported class type being “Trojan-activity” followed by “Policy-violation” and “Misc-activity”. Some less frequently reported class types such as “Attempted-admin” and “Web-application-attack” are particularly interesting in the context of detecting malicious inbound and outbound network traffic.

Snort rules are identified from three parts. The Generator ID (GID), the rule ID (SID) and revision number. The GID identifies what part of Snort generates the event; ‘1’ indicates an event has been generated from the text rules subsystem. The SID uniquely identifies the rule itself. You can search for information on SIDs via the search box on the Snort website. The revision number is the version of the rule; be sure to use the latest revision of any rule.

Without a further ado, here are the top 5 triggered rules within policy in reverse order, just as you would expect from a yearly Top of the Snort alerts chart.

#5 - 1:39867:3 “Suspicious .tk dns query”

The .tk top level domain is owned by the South Pacific territory of Tokelau. The domain registry allows for the registration of domains without payment, which leads to the .tk top level domain being one of the prolific in terms of number of domain names registered. However, this free registration leads to .tk domains frequently being abused by attackers.

This rule triggers on DNS lookups for .tk domains. Such a case doesn’t necessarily mean that such a lookup is malicious in nature, but it can be a useful indicator for suspicious activity on a network. A sharp increase in this rule triggering on a network should be investigated as to the cause, especially if a single device is responsible for a large proportion of these triggers.

Other, similar rules detecting DNS lookups to other rarely used top level domains such as .bit, .pw and .top also made into our list of top 20 most triggered rules.

#4 - 1:23493:6 “Win.Trojan.ZeroAccess outbound connection”

ZeroAccess is a trojan that infects Windows systems, installing a rootkit to hide its presence on the affected machine and serves as a platform for conducting click fraud campaigns. This rule detects UDP packets sent by an infected system to so called super nodes, which participate in the network of command and control servers. The rule can be used to block outbound communication from the malware.

ZeroAccess is a state of the art rootkit and is able to hide from the basic detection techniques on the infected machine. However, network detection using IPS such as Snort can quickly pinpoint a source of the malicious ZeroAccess traffic as it generates a fairly noisy and regular communication pattern.

The malware sends a UDP packet to check with a super node once every second, so a single affected organization is expected to have many alerts. This may be one of the reasons why the ZeroAccess detection rule is placed high on our list.

#3 - 1:41083:1 “suspicious .bit dns query”

The .bit top level domain extension is relatively obscure, but is occasionally used for hosting malware C2 systems with Necurs being one of the families using it as a part of the botnet communication. The .bit TLD is managed using Namecoin, a distributed ledger with no central authority that is one of the first forks of the Bitcoin cryptocurrency. The decentralised nature of .bit domains means that few DNS servers resolve the domains, but equally the domains are resistant to take down.

The rule triggers on DNS lookups for .bit domains. As with .tk lookups, if the rule triggers, this doesn’t necessarily mean that such a lookup is malicious in nature. However, a sharp increase in the rule triggering may warrant investigation.

#2 - 1:42079:1 “Win.Trojan.Jenxcus outbound connection attempt with unique User-Agent”

Jenxcus is more of a worm than a trojan, despite the naming used in the human readable description of the rule. It spreads by copying itself to removable and shared drives and allows the attacker to remotely access and control the infected system. Like many trojans, once a system is infected, Jenxcus seeks to establish contact with its’ C2 infrastructure. This contact is made with a HTTP POST request using a specific user-agent string. The user-agent string itself is specific to this trojan and its many variants, and can be detected and blocked using this rule.

#1 - 1:40522:3 “Unix.Trojan.Mirai variant post compromise fingerprinting”

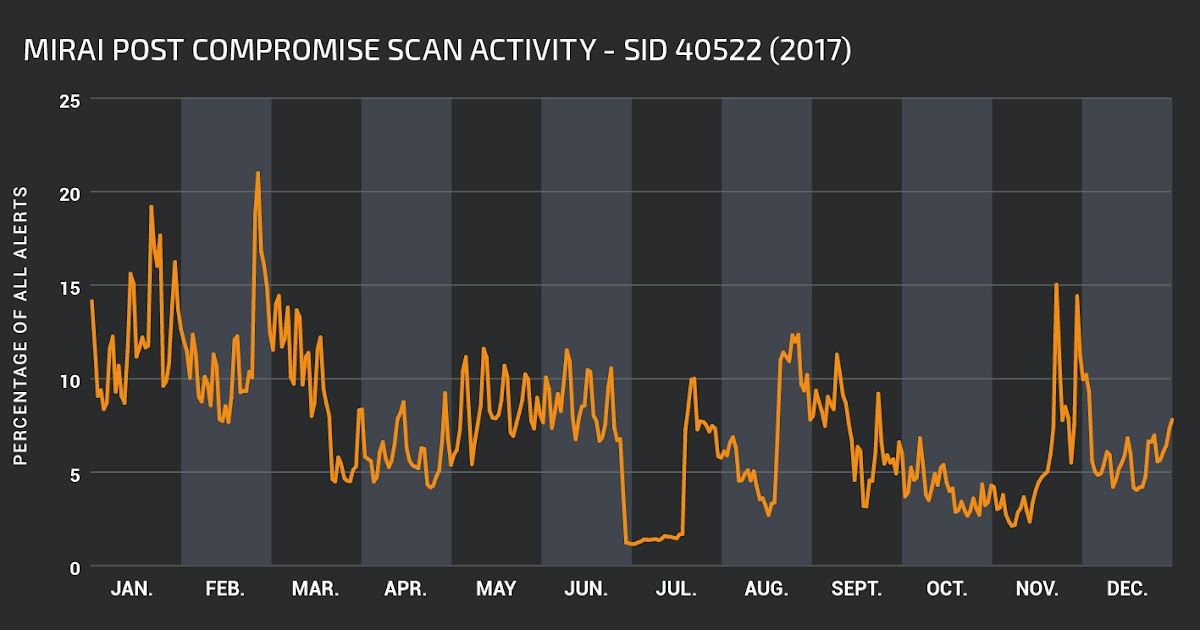

Internet of Things (IoT) security is something which we have written about extensively. The Mirai botnet, and variants, continue to try and infect IoT devices through attempting to login with default usernames and passwords. Once the malware successfully accesses a device, it will check that the device behaves as expected and not like a honeypot. It is this check which is detected by this rule. This post compromise activity has been constantly present throughout the year and at the peak of its activity in February accounted for over 20% of all alerts reported daily.

Inbound, Outbound or Internal

Network traffic can cross an IDS from external to internal (inbound) from the internal to external (outbound) or pass the sensor without traversing it, as internal traffic. An alert may be triggered and logged for any of these scenarios.

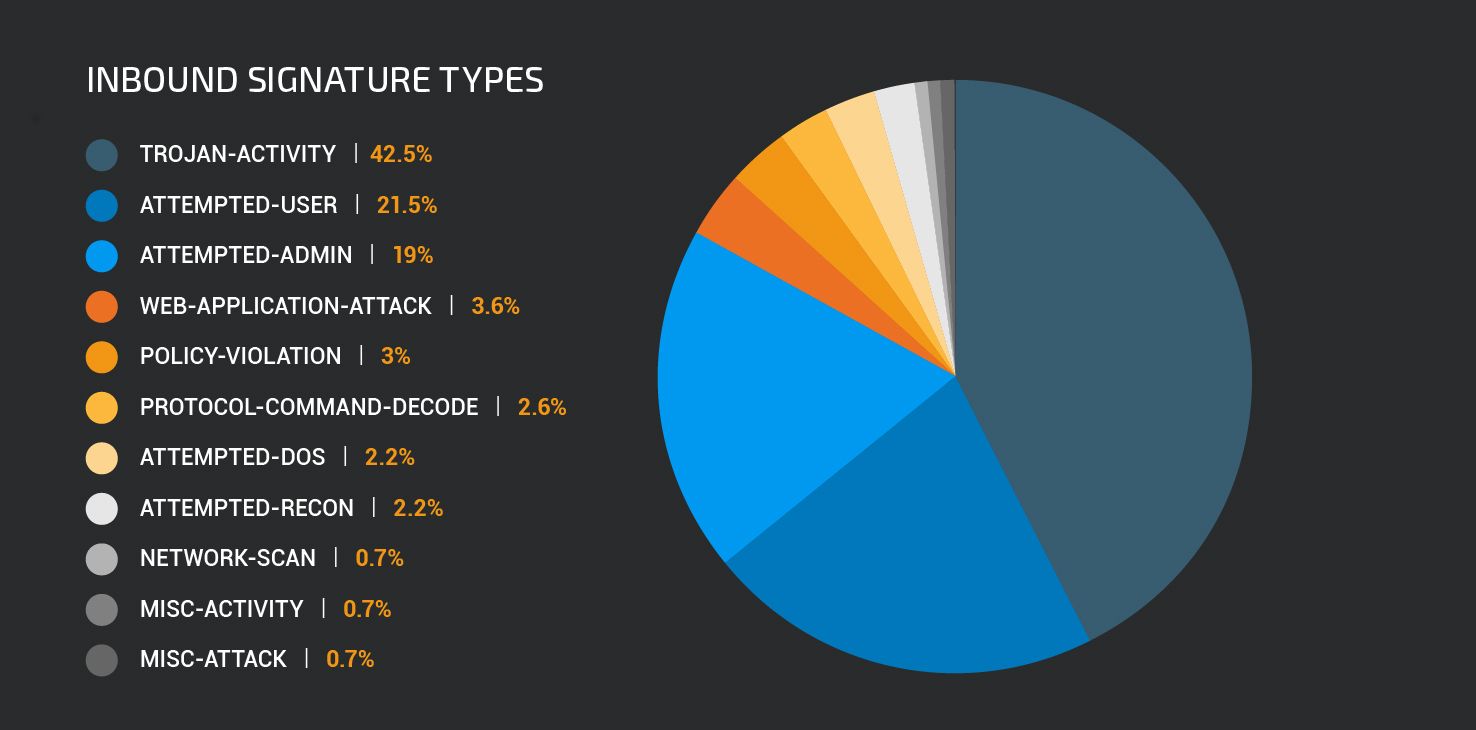

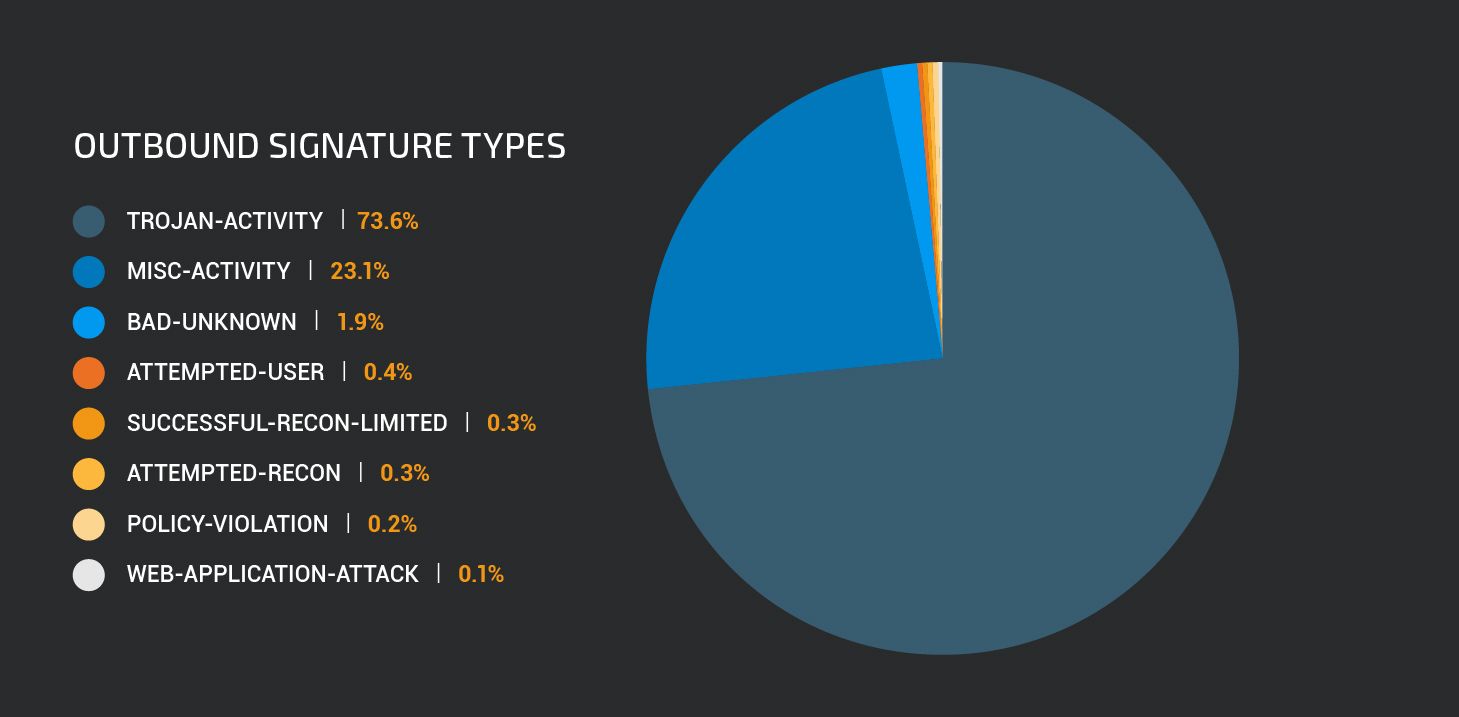

Outbound rules were triggered during 2017 much more frequently than internal, which in turn were more frequent than inbound with ratios of approximately 9:6:5. The profile of the alerts are different for each direction. Inbound alerts are likely to detect traffic that can be attributed to attacks on various server-side applications such as web applications or databases. Outbound alerts are more likely to contain detection of outgoing traffic caused by malware infected endpoints. Internal alerts are most likely to be due to trojan or miscellaneous activity.

Looking at these data sets in more detail gives us the following:

“Trojan-activity” class type alerts were dominated by the Mirai post compromise fingerprinting attempts, but this category also contains blocked attempts to download executable files disguised as plain text, and traffic associated with Zeus, Swabfex, Soaphrish, Glupteba malware.

The “Attempted-user” class type covers attempts to exploit user level vulnerabilities. The majority of the most frequently triggered rules in this set were detected attempts to exploit Internet Explorer vulnerabilities.

Outbound rules most frequently reported class types of detections triggering on internal network traffic belong to the “Misc-activity” and “Trojan-activity” classes.

The most frequently triggered rule within the “Trojan-activity” rule class are the Jenxcus and .bit dns activity rules discussed above. Other prevalent trojan activity is related to ZeroAccess, Cidox, Zeus and Ramnit trojans.

Internal traffic rule types most frequently reported detection class types belong to the “Misc-activity” and “Trojan-activity” classes.

Misc activity rules include detections for various traffic patterns which do not easily fit into any other specific class types. This includes detection of DNS requests to less common top level domains like .top, .win, .trade, detection of traffic to domains known to be used by adware and other potentially unwanted applications (PUAs) as well as detection of suspicious HTTP user-agent strings.

Peaks and Troughs

Attacks are happening continuously. Every hour of the day, every day of the year rules are being triggered by the constant background noise of the attackers’ activity. However, some rules are clearly triggered by malicious activity being conducted during a particular period.

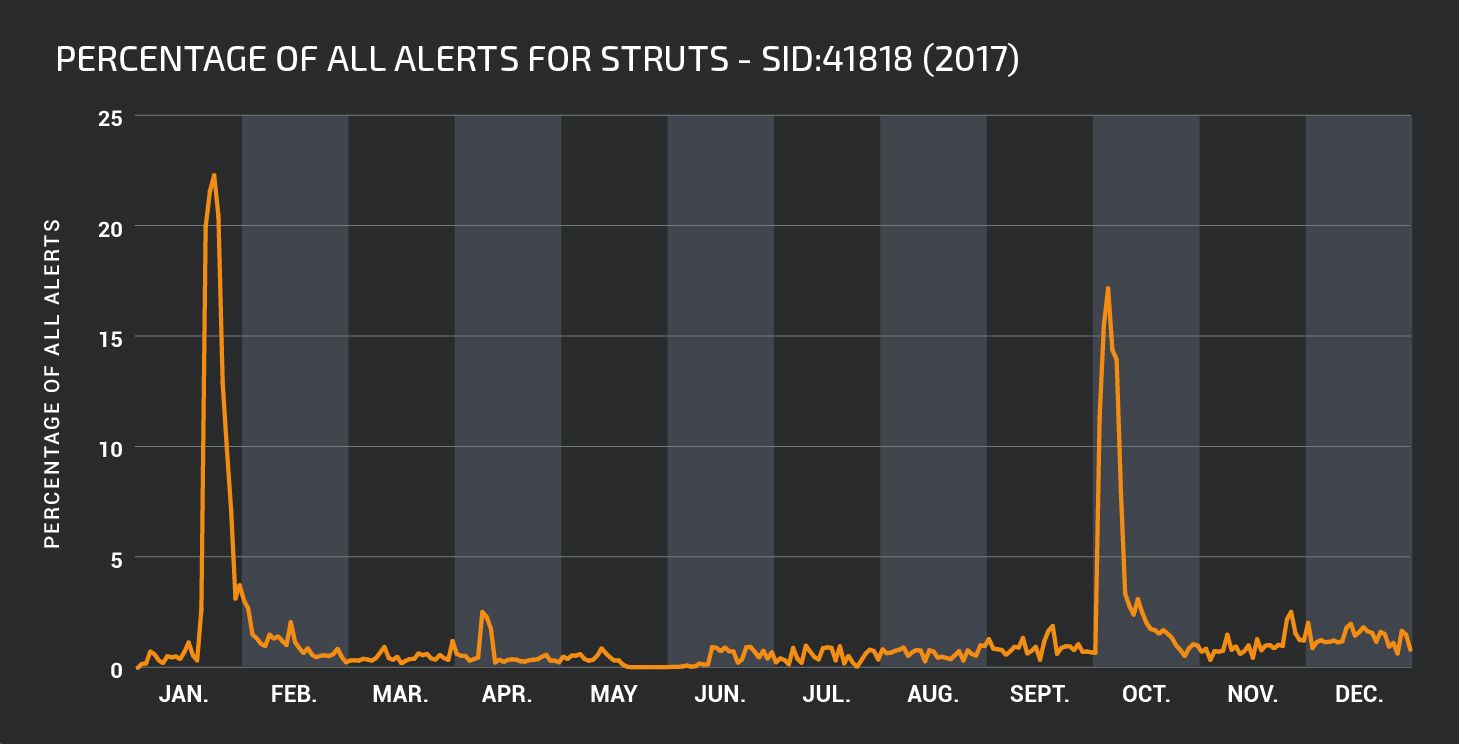

On March 6th, Apache disclosed an Apache Struts command injection vulnerability CVE-2017-5638. Talos released rule 1:41818 to detect and block exploitation of the vulnerability. Within a couple of days, attackers were conducting widespread campaigns to identify and compromise vulnerable systems.

As shown in the graph below, attempts to exploit CVE-2017-5638 comprised more than 20% of all triggering rules at the peak of the malicious activity. This campaign soon abated, but never ceased completely, until a second large peak in activity occurred over 6 days at the end of October.

This graph neatly illustrates the importance of patching as well as installing and enabling rules for new vulnerabilities as soon as possible. There may be a very short period of time between the disclosure of a vulnerability and the widespread attempted exploitation of the vulnerability by threat actors.

Similarly, once an initial attempt to compromise is over, the same attack may recommence some time later, so defences need to be maintained in order to ensure that systems are kept protected.

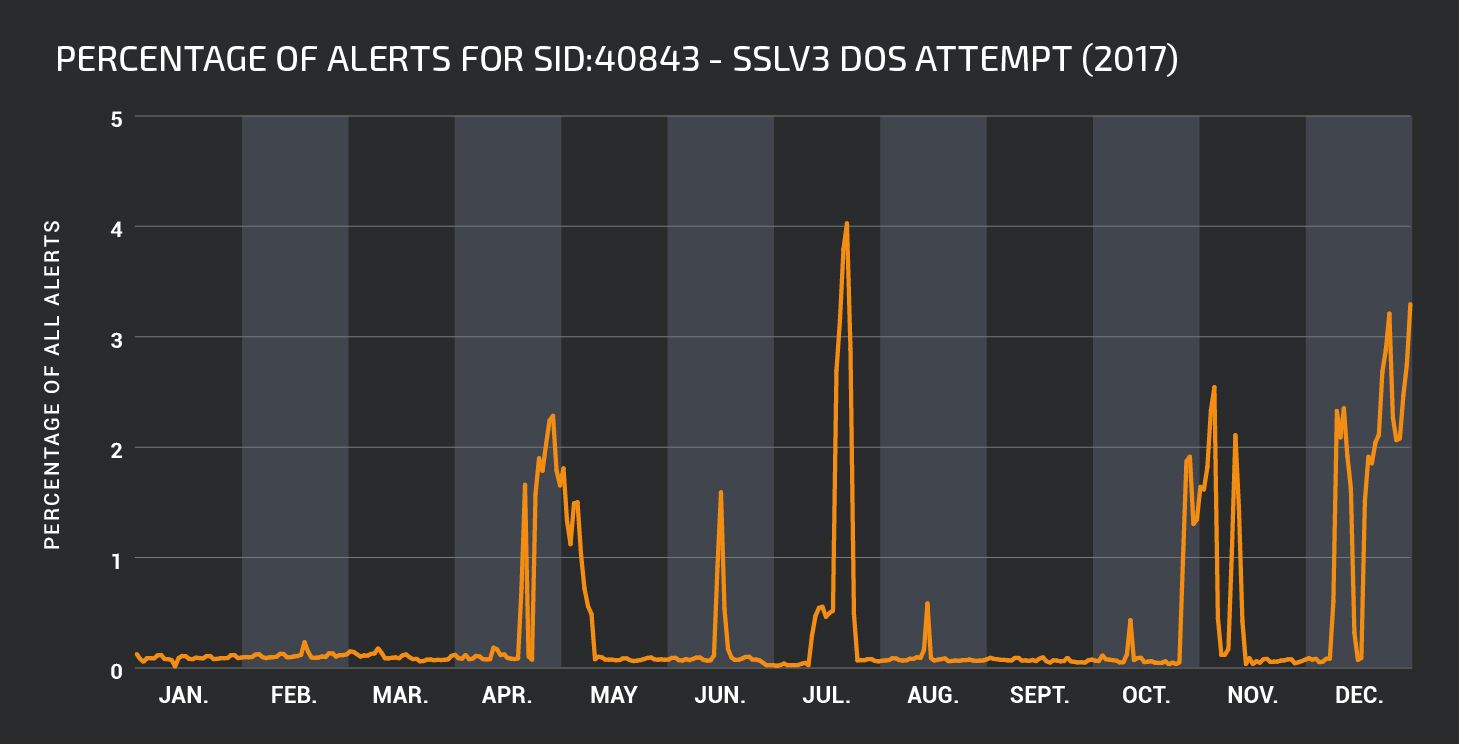

Another interesting pattern showing several periods of increased activity can be seen in the timeline for rule 1:40843. This rule detects and blocks the so called SSL Death Alert Denial of Service vulnerability in OpenSSL (CVE-2016-8610). An attacker can exploit vulnerable systems over the network to consume 100% CPU, preventing the system from responding to legitimate requests.

For extended periods during 2017, this vulnerability was not heavily targeted by attackers. However there are very clear periods when attackers were conducting campaigns to exploit this vulnerability.

Our primary advice is to install patches as soon as possible. However, patched versions of some software packages are not being released for this vulnerability. In this case, upgrading to a non-vulnerable version would be the preferred option, but this may not be possible in every case. Ensuring that vulnerable systems are protected by IPS with the relevant rules installed and enabled, helps keep malicious traffic from impacting unpatched vulnerable systems.

Discussion

Snort rules detect potentially malicious network activity. Understanding why particular rules are triggered and how they can protect systems is a key part of network security. Snort rules can detect and block attempts at exploiting vulnerable systems, indicate when a system is under attack, when a system has been compromised, and help keep users safe from interacting with malicious systems. They can also be used to detect reconnaissance and pre-exploitation activity, indicating that an attacker is attempting to identify weaknesses in an organization’s security posture. These can be used to indicate when an organization should be in a heightened state of awareness about the activity occurring within their environment and more suspicious of security alerts being generated.

As the threat environment changes, it is necessary to ensure that the correct rules are in place protecting systems. Usually, this means ensuring that the most recent rule set has been promptly downloaded and installed. As shown in the Apache Struts vulnerability data, the time between a vulnerability being discovered and exploited may be short.

Our most commonly triggered rule in 2017: 1:40522:3 “Unix.Trojan.Mirai variant post compromise fingerprinting” highlights the necessity of protecting IoT devices from attack. Malware such as Mirai seeks to compromise these systems to use them as part of a botnet to put to use for further malicious behaviour. Network architectures need to take these attacks into consideration and ensure that all networked devices no matter how small are protected.

Security teams need to understand their network architectures and understand the significance of rules triggering in their environment. For full understanding of the meaning of triggered detections it is important for the rules to be open source. Knowing what network content caused a rule to trigger tells you about your network and allows you to keep abreast of the threat environment as well as the available protection.

At Talos, we are proud to maintain a set of open source Snort rules and support the thriving community of researchers contributing to Snort and helping to keep networks secure against attack. We’re also proud to contribute to the training and education of network engineers through the Cisco Networking Academy, as well through the release of additional open-source tools and the detailing of attacks on our blog.

There is no doubt that 2018 will bring its own security challenges and it will be interesting to follow how reported detections are evolving over the year together with new threats. We will make sure to keep you up to date with events relevant to your organizations and networks.