Cisco Talos recently covered the basics of NIS2, a new set of requirements for cybersecurity and security incident disclosures set to take effect next year in the European Union.

As part of these new guidelines, organizations with operations in the EU must have up-to-date “incident handling” procedures and “policies on risk analysis and information system security”

To comply, Talos IR recommends creating or updating your organization’s incident response (IR) plan, along with the Information Security Policy, Business Continuity and Crisis Management Plan. The IR plan is a crucial document for each organization’s cybersecurity practice and should be among the first documents to be updated to comply with NIS2.

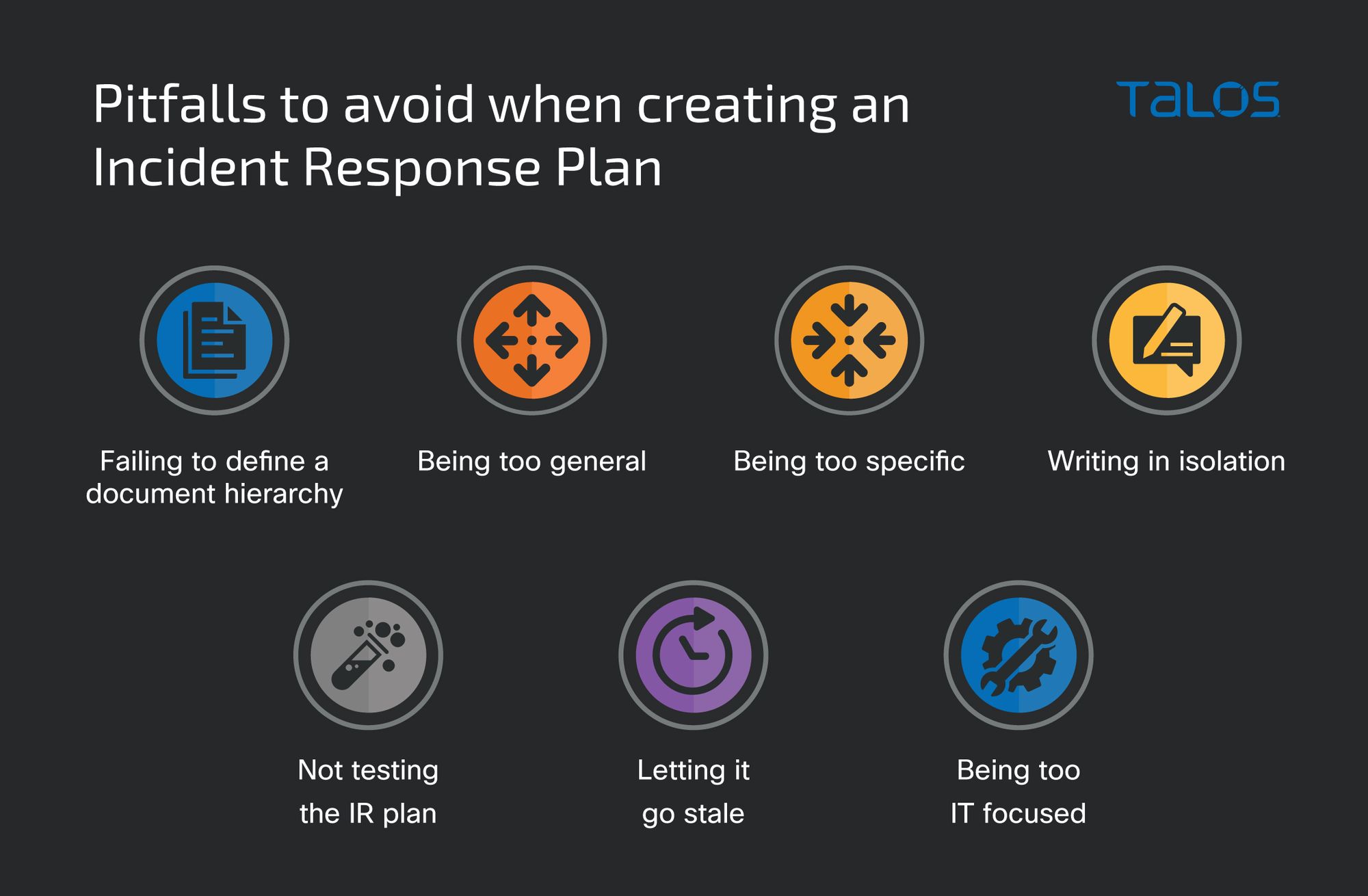

Below, we’ll outline seven common pitfalls that organizations make when creating or updating an incident response plan. Avoiding some of these common mistakes ensures your organization’s plan will be updated faster and is more thorough, so you are ready to act when, not if, an incident happens.

Part II: Pitfalls to avoid when creating an incident response plan

Failing to define a document hierarchy

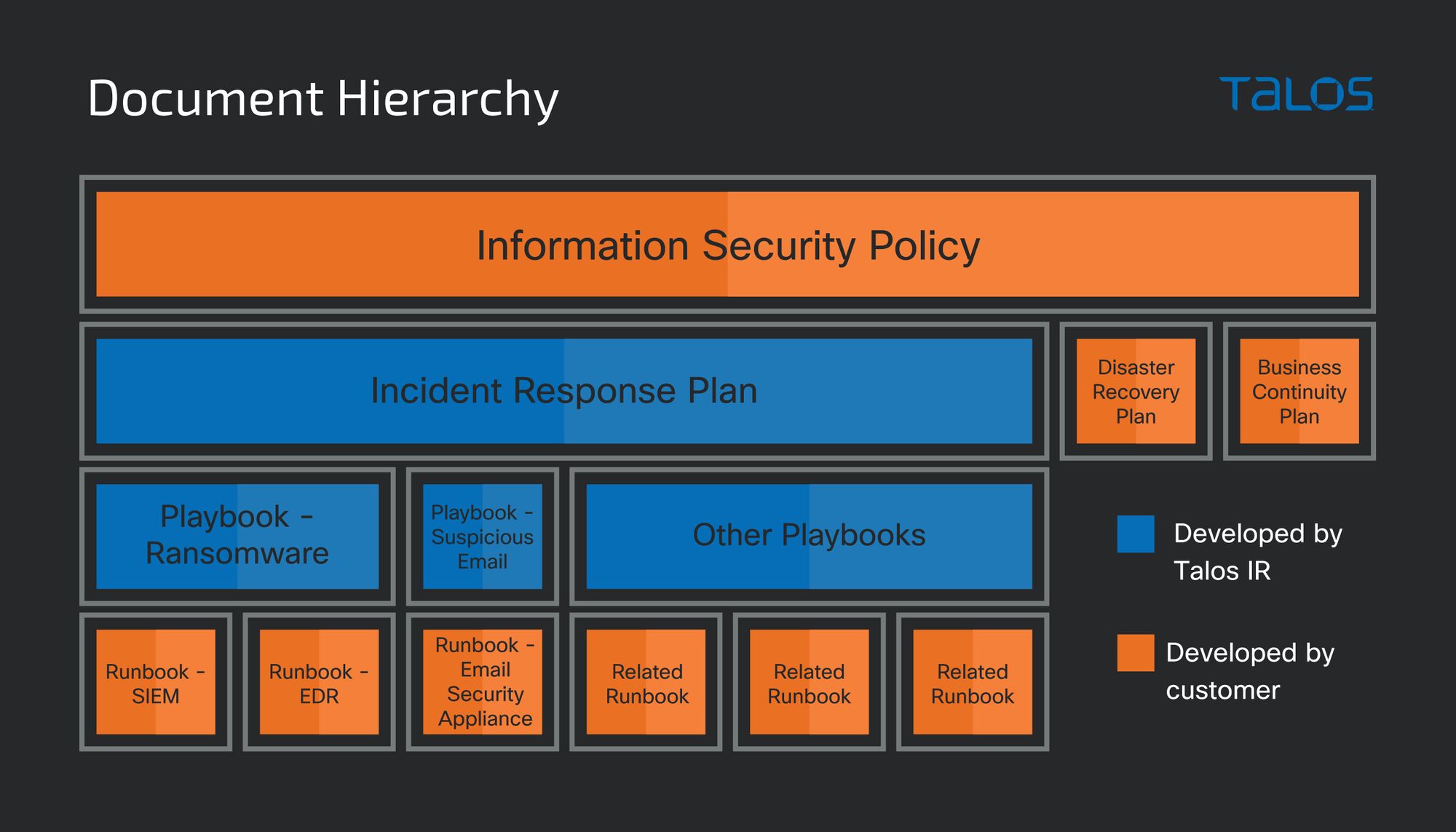

A common mistake when starting to work on a new or updated IR plan is to look at the plan in isolation, without consideration for all the cybersecurity documents that exist in your organization.

The term “document hierarchy" might sound complicated and foreign, but it describes exactly this simple concept: All documents within an organization should have a specific scope, purpose and intended audience — A bit like LEGO blocks that build upon each other.

Document B can deepen the information presented in Document A by providing more details on a specific part of the process without the need to repeat what was already presented in Document A. Having a clear overview on how the individual documents fit within the overall document hierarchy helps avoid duplication of information, thus keeping documents only as long as they really need to be. A shorter document with a clear focus is more likely to be read and effectively used by its intended audience.

In the context of cybersecurity, Talos IR recommends a document hierarchy consisting of the following building blocks:

The incident response plan focuses on the incident handling process. It is a second- or third-level document that builds on the higher-level information in the security policy or the security principal statement. In the plan, which has a narrower audience than the previous two documents, one can find details on the formation and operations of the incident response team, actions and available resources in each phase of the incident response process, escalation procedures and communication flows. The information in the incident response plan is applicable to all cybersecurity incidents and serves as a basis for the development of the next level of documentation, which is more procedural and scenario-based.

By failing to define and adhere to a clear document hierarchy you run the risk of overloading the IR plan with specific checklist type of information, which would be more fitting for a playbook. Playbooks usually build upon the incident response plan to provide step-by-step guidance for responding to a specific incident type, such as ransomware, suspicious emails, and unusual network traffic. Another risk is the plan is too broad, borrowing content from the policy and listing general cyber hygiene advice and end-user training topics. This makes it hard for the responders, who are the main audience of the plan, to find the vital information for their needs.

Being too general

An Incident Response Plan should at the very least answer the “Who, What, When and How?” of a cybersecurity incident.

If you break it down:

- Who – What are the roles that are part of the IR process, what skillsets or capabilities are required for the members of the role (technical and in terms of crisis management and coordination), and what other supporting roles are involved during the different IR phases.

- What – What activities are performed at each stage of the incident response process? Remember, an IRP is not a playbook, so you do not need to describe the details of, for example, investigating suspicious executable files on a host. Instead, the plan should have a description of the general triage process, available data sources within the organization and possible playbooks to follow once the incident has been narrowed down.

- When – Time is precious during an incident, so it is good to have an order of actions that is pre-determined to take place whenever an incident occurs. For example, based on the priority classification of the incident (which is something that should also be in the plan) an escalation process might be started. Would a high-priority event occurring on the weekend necessitate calling immediately the manager immediately? Is such an escalation point available outside of normal working hours? Each action should also have a role owner identified.

- How – An incident response plan should contain high-level information about the tools that would typically be used during an incident for the technical response (including data capturing, detection capabilities and analysis tools) and the incident communication (e.g., what alternative infrastructure can be used if the network is suspected to be compromised). Yet, the plan should offer only an overview of the capabilities of the tools, the toolkit at the team’s disposal, rather than procedural details on using them. The latter should be added to the organization’s playbooks.

Being too specific

An IRP is not a playbook. The information in the plan is the foundation that doesn’t need to be repeated in the other playbooks. For example, ensure that the plan does not include procedural information that is only applicable to one type of attack, such as ransomware or distributed denial-of-service (DDoS), because this will water down the scope of the document.

Writing in isolation

In all fairness, few technical personnel are truly enthusiastic about writing process documentation. This makes it even more important to ensure that whoever works on the IR plan is supported by the broader team.

One of the most successful ways to create a meaningful IR plan is to involve the company stakeholders, such as the primary business application owners, so they can have an understanding and make sure their needs and expectations are being met with the plan.

The initial plan draft should be reviewed by at least two team members who have process knowledge and will be responsible for the IR process implementation. Then, the next level of review should be done by teams outside of the core IR team, such as Networking and Storage Management, which play a key role during recovery. Supporting non-technical teams such as legal, communications and HR, should be provided with a final draft for review. The input of the latter is just as valuable as the technical ones, because some regulations, such as NIS2, will require incident notification within 24 hours. For example, it would be up to the legal team to confirm if, and who will be available on the weekend to contact law enforcement for an incident that started on a Friday afternoon and by Sunday needs to be reported.

Not testing the IR plan

We all know that testing processes are essential, but not all processes are created equal. How often do you test your backup recovery procedure? And how often do you test your incident response process?

An Incident Response Plan typically contains several sub-process descriptions, such as an escalation process, triage process, alternative communication channels activation process, etc. The plan is only as good as its use during a real incident, and the best way to identify any gaps in any of those sub-processes is to put them to a test.

How can you test the IR Plan? Start by breaking it down into key processes which are part of the overall incident handling. Then rank those processes according to their criticality for the overall response and their level of effort to test. Start with the sub-processes on top and work your way down.

For example, look at the recovery action, “the incident lead contacts the backup management team to get the status of the backups.” Here are some of the questions that you might need to check:

- How does the incident commander contact the backup management team? Is that communication channel available offline if the company’s communications tools are down or compromised?

- Will the backup management team be available at this time of the day? What if the incident happens on the weekend or during a public holiday?

- Where will the backup management team find the latest test date of the backups? Does the backup management team have a procedure to follow during the verification of the backup’s integrity? How quickly such an overview be created?

- If backups have been isolated, could they be checked for integrity?

- In case of a suspicion of compromise, does the backup management team have a list of all accounts that have access to the backups?

- How will the incident commander keep track of all information sent to them during the incident and make them available to the larger team?

To test the tools, people and processes involved in this situation, Talos IR recommends conducting tabletop exercises at least once a year. A tabletop is a dry run through a scenario customized to your organization, the attack being only on paper without environmental impact, to see how responsible teams will react. It might seem harmless but if done properly, the tabletop can empower teams to see their IR plan with new eyes, discovering both the power of a well-written document with up-to-date information and the areas that need improvement.

Letting it get stale

An IRP should be renewed and updated at least once a year, and additionally, whenever you have major software or hardware changes in your environment. Changes in the organization's legal structure, such as mergers and acquisitions, also necessitate a review. At the conclusion of any major incidents, it is also recommended to review the IR Plan and adjust based on the incident. Regular reviews also help ensure that in case of personnel changes — e.g., members rotating outside the team or the organization, or IT landscape changes — the plan is still effective.

Being too IT-focused

An IR plan should be created in consultation with other non-technical teams, starting with legal, compliance, HR and communications. Specific examples of when you will need to work closely with those teams are cases when the personal data of employees has been affected, when you have regulatory requirements to notify authorities about an incident, or when you need to publish a public statement about a major incident.

Another team that is often overlooked but should be part of the IR plan development is the service desk team. Are agents able to route a cybersecurity incident properly and get it quickly escalated to the IR team? Have they been trained to recognize, even with fewer affected users, high-confidence signs of common attacks such as ransomware, wipers and social engineering?

If you remain too focused on the technical aspects of handling an incident, you run the risk of creating an incomplete document. Supporting teams should be part of the development process, the distribution list of the final document, and the testing and training exercises. Raising a child takes a village, and so does protecting an organization.

Talos IR can support customers in preparing to meet the requirements of NIS2. The following services address one or more of the requirements of the directive:

- Preparing: IR Plan, IR Playbooks, IR Readiness Assessment, Log Architecture Assessment

- Simulating: Purple Team

- Training: Tabletop , Cyber Range

- Hunting: Compromise Assessment, Threat Hunting

- Core: Emergency Response, Intel on Demand

The implementation of technical and procedural measures, which would support you in achieving compliance with NIS2, is a process that might require creating new processes and updating your technology stack. Time flies when you are having fun so we recommend that you start by reviewing the requirements you will need to comply with and putting together an actionable plan for how to achieve this in the course of the upcoming year.