Summary

Absent contributions from traditional intelligence capacities, the available evidence linking the Olympic Destroyer malware to a specific threat actor group is contradictory, and does not allow for unambiguous attribution. The threat actor responsible for the attack has purposefully included evidence to frustrate analysts and lead researchers to false attribution flags. This false attribution could embolden an adversary to deny an accusation, publicly citing evidence based upon false claims by unwitting third parties. Attribution, while headline grabbing, is difficult and not an exact science. This must force one to question purely software-based attribution going forward.

Introduction

The Olympic Games in Pyeongchang, South Korea were disrupted by a cyber attack earlier this month. Reportedly, the attack resulted in the Olympic website being knocked offline, meaning individuals could not print their tickets. Reporting on the opening ceremony was also degraded due to WiFi failing for reporters on site. On Feb. 12, Talos published a blog detailing the functionality of the malware Olympic Destroyer that we have identified with moderate confidence as having been used in the attack.

Example press quotes suggesting attribution for Olympic Destroyer.

The malware did not write itself, the incident did not happen by accident, but who was responsible? Attributing attacks to specific malware writers or threat actor groups is not a simple or exact science. Many parameters must be considered, analysed and compared with previous attacks in order to identify similarities. As with any crime, criminals have preferred techniques, and tend to leave behind traces, akin to digital fingerprints, which can be found and linked to other crimes.

In terms of cyber security incidents, analysts would look for similarities for attributes such as:

- Tactics, Techniques and Procedures (TTPs) (how the attacker conducted the attack)

- Victimology (the profile of the victim)

- Infrastructure (the platforms used as part of the attack)

- Indicators of Compromise (IOCs) (identifiable artifacts left during an attack)

- Malware samples (the malware used as part of the attack)

One of the strengths of software engineering is the ability to share code, to build applications on top of libraries written by others, and to learn from the success and failures of other software engineers. The same is true for threat actors. Two different threat actors may use code from the same source in their attacks, which means that their attacks would display similarities, despite being conducted by different groups. Sometimes threat actors may choose to include features from another group in order to frustrate analysts and try to lead to making a false attribution.

In the case of Olympic Destroyer, what is the evidence, and what conclusions regarding attribution can we make?

Olympic Destroyer Lineup of Suspects

The Lazarus Group

The Lazarus Group, also referred to as Group 77, is a sophisticated threat actor that has been associated with a number of attacks. Notably, a spinoff of Lazarus, referred to as the Bluenoroff group, conducted attacks against the SWIFT infrastructure in a bank located in Bangladesh.

The filename convention used in the SWIFT malware, as described by BAE Systems, was: evtdiag.exe, evtsys.exe and evtchk.bat.

The Olympic Destroyer malware checks for the existence of the following file: %programdata%\evtchk.txt.

There is a clear similarity in the two cases. This is nowhere near proof, but it is a clue, albeit weak.

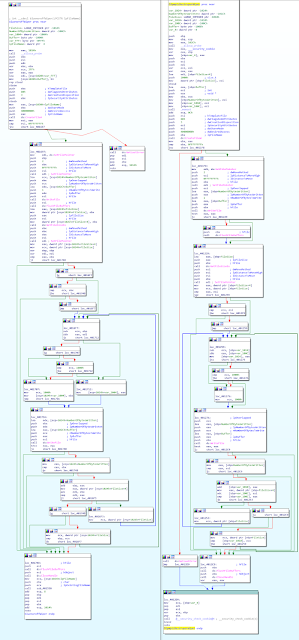

Further evidence is found in similarities between Olympic Destroyer and the wiper malware associated with Bluenoroff, again described by BAE Systems. In this example, the Bluenoroff wiper is on the left, and the Olympic Destroyer wiper function on the right:

Clearly, the code is not identical, but the very specific logic, of wiping only the first 0x1000 bytes of large files is identical and unique to both cases. This is another clue, and stronger evidence than the file name check.

However, both the file names used by Bluenoroff and the wiper function are documented and available to anyone. Our actual culprits could have added the file name check, and mimicked the wiper function simply in order to implicate the Lazarus group and potentially distract from their true identity.

Olympic Destroyer sample: 23e5bb2369080a47df8284e666cac7cafc207f3472474a9149f88c1a4fd7a9b0

Bluenoroff sample #1: ae086350239380f56470c19d6a200f7d251c7422c7bc5ce74730ee8bab8e6283

Bluenoroff sample #2: 5b7c970fee7ebe08d50665f278d47d0e34c04acc19a91838de6a3fc63a8e5630

APT3 & APT10

Intezer Labs spotted code sharing between Olympic Destroyer and malware used in attacks attributed to APT3 and APT10.

Intezer Labs identified that Olympic Destroyer shares 18.5 percent of its code with a tool used by APT3 to steal credentials from memory. Potentially, this is a very strong clue. However, the APT3 tool is, in turn, based on the open-source tool, Mimikatz. Since Mimikatz is available for download by anyone, it is entirely possible that the author of Olympic Destroyer used code derived from Mimikatz in their malware, knowing that it had been used by other malware writers.

Intezer Labs also spotted similarities in the function used to generate AES keys between Olympic Destroyer and APT10. According to Intezer Labs, this particular function has only ever been used by APT10. Maybe the malware writer has let slip a possible vital clue to their identity.

Nyetya

The use of code derived from Mimikatz to steal credentials was also seen in the Nyetya (NotPetya) malware of June 2017. Additionally, like Nyetya, Olympic Destroyer spread laterally via abusing legitimate functions of PsExec and WMI. Like Nyetya, Olympic Destroyer uses a named pipe to send stolen credentials to the main module.

Unlike Nyetya, Olympic Destroyer didn't use the exploits EternalBlue and EternalRomance for propagation. But, the perpetrator has left artifacts within the Olympic Destroyer source code to insinuate the presence of SMB exploits.

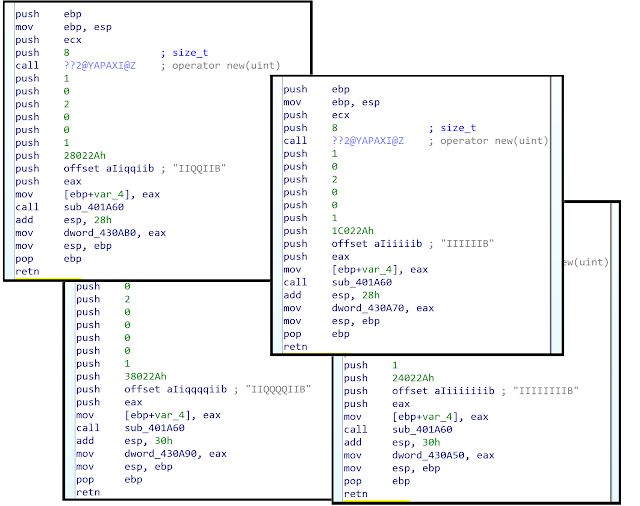

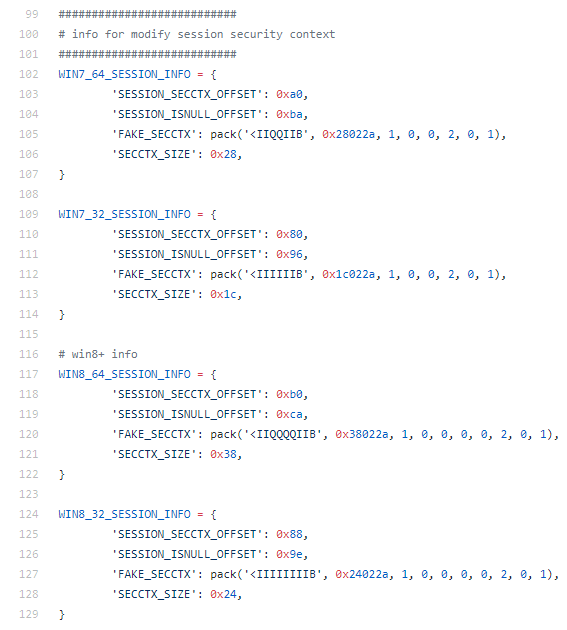

Olympic Destroyer includes the definition of these four structures:

These four structures can also be found in the public EternalBlue proof of concept:

These structures are loaded during runtime, when the Olympic Destroyer is executed, but remain unused. Clearly, the author knew of the EternalBlue PoC, but the reason why these structures are present is obscure. It's likely the author wanted to lay a trap for security analysts to provoke a false positive attribution. Alternatively, we could be seeing the traces of functionality, which never made it into the final malware.

Conclusion

Attribution is hard. Rarely do analysts reach the level of evidence that would lead to a conviction in a courtroom. Many were quick to jump to conclusions, and to attribute Olympic Destroyer to specific groups. However, the basis for such accusations are frequently weak. Now that we are potentially seeing malware authors placing multiple false flags, attribution based off malware samples alone has become even more difficult.

For the threat actors considered, there is no clear smoking gun indicating a guilty party with the evidence which we have available. Other security analysts and investigative bodies may have further evidence to which we do not have access. Organisations with additional evidence, such as signal intelligence or human intelligence sources which may provide significant clues to attribution, may be the least likely to share their insights so as not to betray the nature of their intelligence-gathering operation.

The attack which we believe Olympic Destroyer to have been associated with was clearly an audacious attack, almost certainly conducted by a threat actor with a certain level of sophistication who did not believe that they would be easily identified and held accountable.

Code sharing between threat actors is to be expected. Open-source tools are a useful source of functionality, and adopting techniques from successful attacks conducted by other groups are likely to be sources of misleading evidence leading to false attribution.

Equally, we can expect sophisticated threat actors to take advantage of this, and to integrate evidence designed to fool analysts, to lead to attribution of their attacks to other groups. Potentially, threat actors take pleasure in reading incorrect information being published by security analysts. This could even be taken to the extreme of a country denying an attack based upon evidence presented by an unwitting third party due to false attribution. Every time there is misattribution it gives adversaries something to hide behind. In this heightened era of fake news attribution is a highly sensitive issue.

As threat actors evolve their skills and techniques, it is likely that we see threat actors further adopting ruses to complicate and confuse attribution. Attribution is already difficult. It is unlikely to become easier.