Executive summary

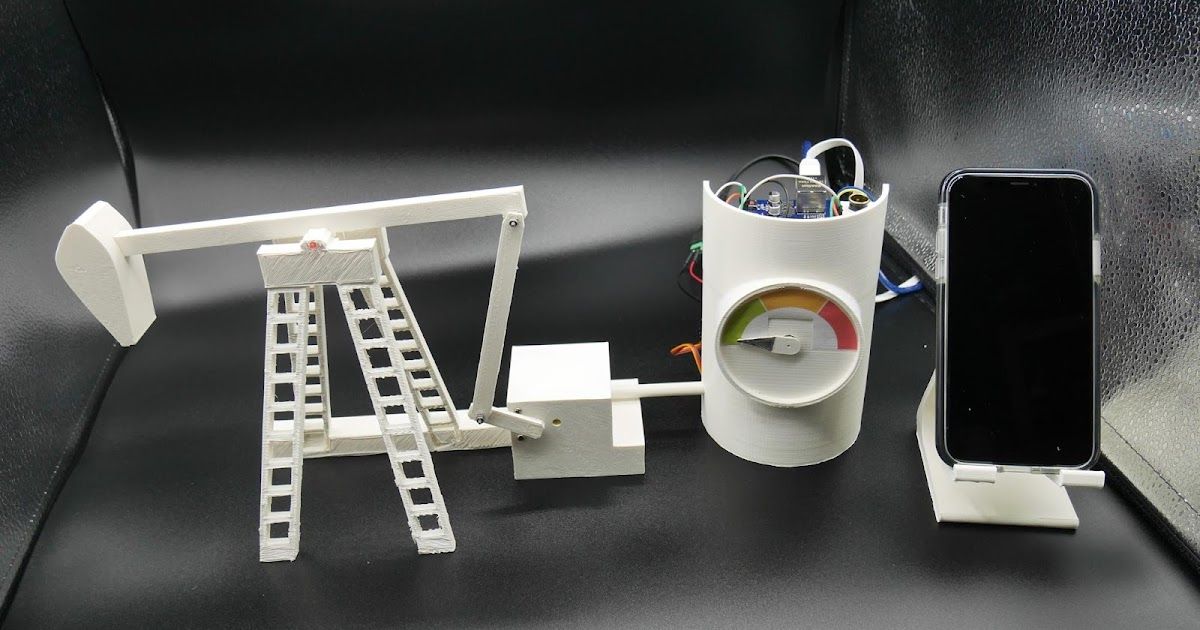

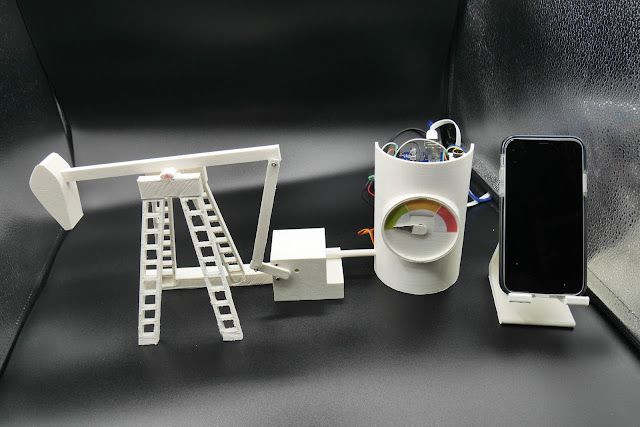

Every day, more industrial control systems (ICS) become vulnerable to cyber attacks. As these massive, critical machines become more interconnected to networks, it increases the ways in which attackers could disrupt their operations and makes it tougher for those who protect organizations' networks to cover all possible attack vectors. To demonstrate how these ICSs interact with a network, we are releasing a model of a 3-D printed oil pumpjack connected to a simulated programmable logic controller (PLC) supporting two industrial protocols. Throughout the year, Talos will have this model at several workshops where attendees can try it out for themselves. For convenience, we are also providing the blueprints and code to even test this out for yourself at home.

We are releasing the 3-D printed model of the pumpjack, the Arduino source code (including the Modbus over TCP and the EtherNet/IP protocols), as well as the code for the human-machine interface (HMI) to control the pump over a network.

To show how serious of a problem it could be if an attacker were to gain control of this device in the real world, here's a GIF that shows how the pump reacts when the motor speed is increased beyond its natural pace.

Hardware description

Global architecture

The project is divided into seven parts:

- The 3-D printed parts.

- The pump, which is controlled by a motor.

- A gauge to show the speed of the motor, activated by a servo-motor.

- An Arduino UNO board, which is the brain of the pump and simulates a PLC.

- An Ethernet Arduino shield for Ethernet support.

- A motor shield to manage the motors and the smoke generator.

- An HMI developed in Python with Flask to monitor and control the pump remotely.

Here are some additional details on these components.

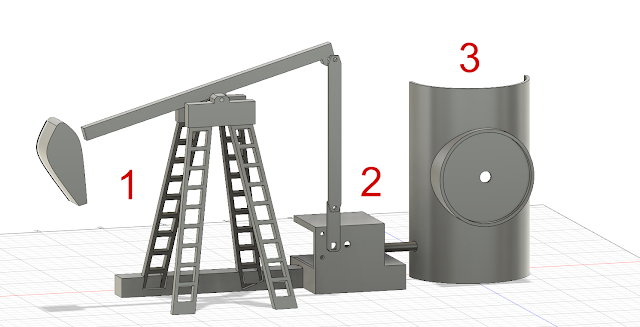

Oil pumpjack 3-D objects

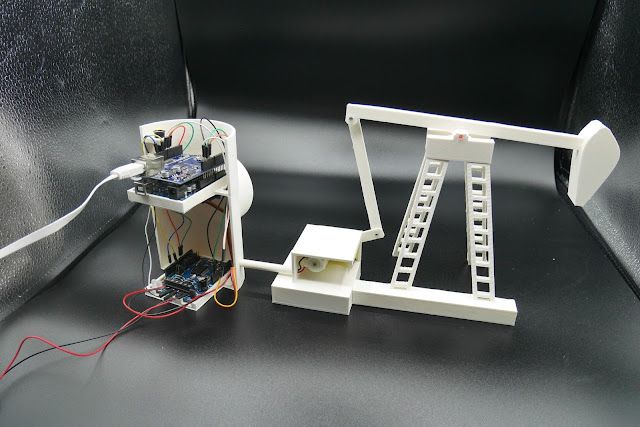

Here is the model of the pump:

- Object 1 is the pump.

- Object 2 is the motor, which activates the pump.

- Object 3 is where the three boards are located. It also contains the gauge that shows the speed level.

The .stl files can be downloaded on our GitHub.

Electronic components

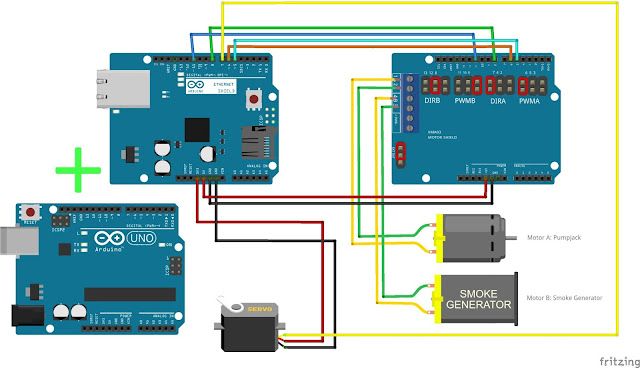

The electronic components, which function as the systems controller, is composed by one Arduino board (Arduino UNO), two shields (Ethernet and Motor), one servo motor, one motor and a smoke generator.

The Arduino UNO and the Ethernet shield (on the left) will be connected directly together. The VMA03 shield (of the right) could be directly connected to. However, during our test, we identified that this component generates a lot of electromagnetic noise. This noise impacted the Ethernet signal. So we decided to separate them:

The Arduino and the Ethernet shield are powered via a USB port. The VM03 shield is powered externally by a 12-volt adapter.

Software

Arduino

The Arduino source code can be downloaded on our GitHub. You can find two projects: The first project supports Modbus over TCP protocol and the second is the EtherNet/IP protocol. For each project, we used Python scripts to test the communication, an HMI, protocol scanner or PCAP of the communication.

Here is an explanation of the Arduino's GPIO pins:

- Motor A (main pump motor) is controlled by the PIN 6 (PWM) and 7 (direction).

- Motor B (the smoke generator) is controlled by the PIN 9 (PWM) and 12 (direction).

- PIN 8 is used by the speed gauge.

- The speed of the motor is defined by arbitrary values between 5,000 and 15,000 — it's set to 8,000 by default. Be careful with this. If the speed gets too high, it can destroy the pump.

- The IP of the pump controller is statically set to 10.10.10.1, you can easily change it in the setup() function.

- In the Modbus over TCP protocol, the speed is located in the register 6 and the gauge value in the register 7. A register is a 16 bits object in the Modbus protocol.

- In the Ethernet/IP protocol, the speed is located in B1:1 and the gauge in B1:7. The Bx:y are tags used by Ethernet/IP to store values.

You can use the serial port in the Arduino IDE to get the debug while the pump is running.

Implemented protocols

Modbus over TCP/IP

The first protocol we implemented is in the Modbus protocol. It was implemented in 1979 by Modicon (now Schneider Electric). It often communicates between controllers and other systems or devices on a TCP network. We recommend reading this page to understand it. We based our implementation of Mudbus library, which supports the following commands:

- Read coil 0x01

- Read register 0x03

- Write coil 0x05

- Write register 0x06

- Write multiple coils, 0x0f

- Write multiple registers 0x10

- Get device information 0x43

The Coils values are stored in the C[] arrays and the values of the register in the R[]. The pump only uses the Register to store the speed of the pump motor and the gauge value.

The device can be queried by using the PyModbus API. Here is an example of the output:

from pymodbus.client.sync import ModbusTcpClient

import sys

client = ModbusTcpClient("10.10.10.1")

result = client.read_holding_registers(6, 1)

print(result.registers)

result2 = client.read_holding_registers(7, 1)

print(result2.registers)

from pymodbus import mei_message

rq = mei_message.ReadDeviceInformationRequest()

result3=client.execute(rq)

print(result3.information)

client.close()

user@lab:~/pumpjack_project/arduino_modbus/python$ ./test.py

[8000]

[73]

{0: 'Talos PLC', 1: 'pumpjack', 2: '0.1'}

Ethernet/IP

We implemented a second protocol used in industrialinfrastructure: EtherNet/IP. This protocol is the adaptation of the Common Industrial Protocol (CIP) to Ethernet. We did not fully implement the protocol; we only support read and write tags. We support the Micrologix or SLC PLCs protocol. The protocol is pretty similar to the Modbus protocol but also includes the notion of the session ID. The session is included in our implementation.

The current version supports Bx:x and Nx:x tags, where x is between 0 and 9.

The device can be queried by using the pycomm API. Here's an example:

from pycomm.ab_comm.slc import Driver as SlcDriver

import logging

c = SlcDriver()

def read_val(num):

print c.read_tag('B1:%d' % num)[3]

if c.open('10.10.10.1'):

read_val(1)

user@lab:~/pumpjack_project/arduino_ENIPCIP/python$ ./test.py

8000

Human-machine interface (HMI)

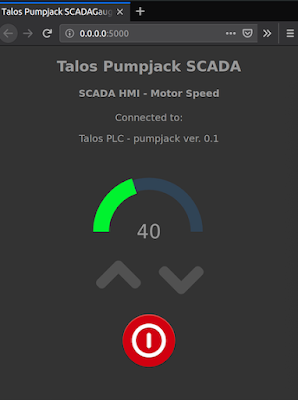

Finally, we provide an HMI to manage the pump. It is developed in Python by using Flask to create the web server and PyModbus to communicate with the pump. Here is a screenshot of the interface:

The web server will first retrieve the pump device name and version via the Modbus over TCP protocol using the "get device information" (0x43) command. It will then retrieve the value of the motor speed and the gauge. The value will determine the gauge level on the web page. By clicking on the increase or decrease button, the motor speed will be increased or decreased by using the Modbus protocol and changing the register 6 value.

Examples of workshop

There are a lot of ways in which researchers could utilize this system to research potential attack vectors on an oil pumpjack. For example, it could be used to understand the two ICS protocols, which are not encountered in traditional IT networks. We can create a packet capture of network traffic on the HMI to perform additional analysis in Wireshark. The built-in Wireshark dissector perfectly parses the Modbus over TCP. The EtherNet/IP protocol dissector is less robust but is able to be partially decoded manually, which is a great exercise. Jared Rittle from Cisco Talos has some of his previous work with the Wireshark dissector available here.

Another scenario could be to scan the local network to identify the Modbus systems and try to modify the pump behaviour by enumerating and then modifying the values stored in the coils and registers. If you are interested in ICS attacks such as Stuxnet — a malicious worm that attacks SCADA systems — you can see the impact of compromising the HMI system and modifying the information provided by the HMI to the operator.

All the scenarios are offensive. We recommend playing the defensive part. For example, SNORT® provides Modbus over TCP support, which you can read the details of here. With this module, you can monitor the traffic, block requests from unauthorized IPs, identify large scans or avoid putting larger values in the registers/coils — and avoid breaking your pumpjack.

Conclusion

We hope these materials help researchers better understand industrial protocols, more particularly Modbus over TCP and EtherNet/IP. These two protocols are unauthenticated protocols always used in production. In the examples, we saw how to modify the internal value of a PLC (simulated by the Arduino UNO). But the PLC programming is performed by this protocol, too. On a real PLC, we can use the same protocol to program it, replace the original code, or patch it. For more information about a real-life PLC attack, we recommend our whitepaper "Process Control through counterfeit comms: Using and abusing built-in functionality to own a PLC," which is available here.

We decided to publicly release our project to make it accessible to the largest audience possible. Do not hesitate to contribute to this project by adding features to the implemented protocols or adding new ones. We would be happy to handle pull requests on our GitHub.