Emotet is still evolving, five years after its debut as a banking trojan. It is one of the world's most dangerous botnets and malware droppers-for-hire. The malware payloads dropped by Emotet serve to more fully monetize their attacks, and often include additional banking trojans, information stealers, email harvesters, self-propagation mechanisms and even ransomware.

At the beginning of June 2019, Emotet's operators decided to take an extended summer vacation. Even the command and control (C2) activities saw a major pause in activity. However, as summer begins drawing to a close, Talos and other researchers started to see increased activity in Emotet's C2 infrastructure. And as of Sept. 16, 2019, the Emotet botnet has fully reawakened, and has resumed spamming operations once again. While this reemergence may have many users scared, Talos' traditional Emotet coverage and protection remains the same. We have a slew of new IOCs to help protect users from this latest push, but past Snort coverage will still block this malware, as well traditional best security practices such as avoiding opening suspicious email attachments and using strong passwords.

Emotet's email propagation

One of Emotet's most devious methods of self-propagation centers around its use of socially engineered spam emails. Emotet's reuse of stolen email content is extremely effective. Once they have swiped a victim's email, Emotet constructs new attack messages in reply to some of that victim's unread email messages, quoting the bodies of real messages in the threads.

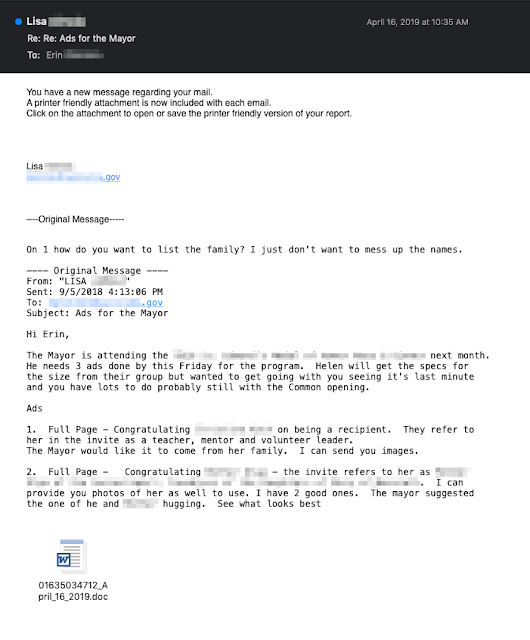

The email above illustrates Emotet's social engineering. In this example, we have a malicious email from Emotet, and contained inside the body of the email we can see a previous conversation between two aides to the mayor of a U.S. city.

- Initially, Lisa sent an email to Erin about placing advertisements to promote an upcoming ceremony where the mayor would be in attendance.

- Erin replied to Lisa inquiring about some of the specifics of the request.

- Lisa became infected with Emotet. Emotet then stole the contents of Lisa's email inbox, including this message from Erin.

- Emotet composed an attack message in reply to Erin, posing as Lisa. An infected Word document is attached at the bottom. It's easy to see how someone expecting an email as part of an ongoing conversation could fall for something like this, and it is part of the reason that Emotet has been so effective at spreading itself via email. By taking over existing email conversations, and including real Subject headers and email contents, the messages become that much more randomized, and more difficult for anti-spam systems to filter.

Emotet's email sending infrastructure

This message wasn't sent using Lisa's own Emotet-infected computer through her configured outbound mail server. Instead, this email was transmitted from an Emotet infection in a completely different location, utilizing a completely unrelated outbound SMTP server.

It turns out that in addition to stealing the contents of victims' inboxes, Emotet also swipes victims' credentials for sending outbound email. Emotet then distributes these stolen email credentials to other bots in its network, who then utilize these stolen credentials to transmit Emotet attack messages.

In the process of analyzing Emotet, Cisco Talos has detonated hundreds of thousands of copies of the Emotet malware inside of our malware sandbox, Threat Grid. Over the past 10 months, Emotet has attempted to use Threat Grid infections as outbound spam emitters nearly 19,000 times.

When Emotet's C2 designates one of its infections as a spam emitter, the bot will receive a list of outbound email credentials containing usernames, passwords and mail server IP addresses. Over the past 10 months, Cisco Talos collected 349,636 unique username/password/IP combos. Of course, many larger networks deploy multiple mail server IP addresses, and in the data we saw a fair amount of repeat usernames and passwords using different, but related mail server IPs. Eliminating the server IP data, and looking strictly at usernames and passwords, Talos found 202,675 unique username-password combinations.

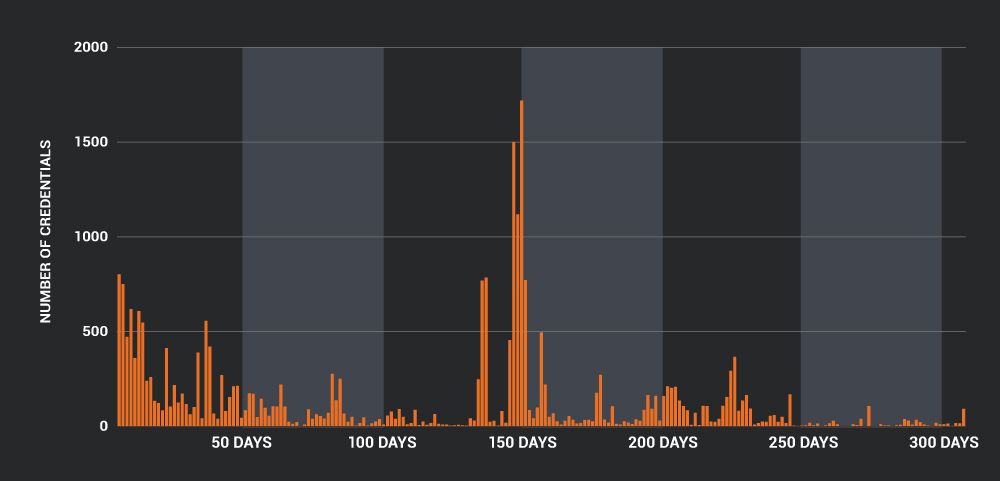

Since Talos was observing infections over a monthslong timeframe, we were able to make an assessment regarding the average lifespan of the credentials we saw Emotet distributing. In all, the average lifespan of a single set of stolen outbound email credentials was 6.91 days. However, when we looked more closely at the distribution, 75 percent of the credentials stolen and used by Emotet lasted under one day. Ninety-two percent of the credentials stolen by Emotet disappeared within one week. The remaining 8 percent of Emotet's outbound email infrastructure had a much longer lifespan.

In fact, we found some outbound credentials that were utilized by Emotet for the entire duration of our sample data. Below is a graph illustrating the volume of credentials having a longer lifespan with days along the X-axis vs. the number of stolen SMTP credentials along the Y-axis. There are quite a few stolen outbound email credentials that Emotet has been using over a period of many months. Talos is reaching out to the affected networks in an attempt to remediate some of the current worst offenders.

Emotet's recipients

As opposed to simply drafting new attack messages, stealing old email messages and jumping into the middle of an existing email conversation is a fairly expensive thing to do. Looking at all the email Emotet attempted to send during the month of April 2019, we found Emotet included stolen email conversations only approximately 8.5 percent of the time. Since Emotet has reemerged, however, we have seen an increase in this tactic with stolen email threads appearing in almost one quarter of Emotet's outbound emails.

Emotet also apparently has a considerable database of potential recipients to draw from. Looking at all of the intended recipients of Emotet's attack messages in April 2019, we found that 97.5 percent of Emotet's recipients received only a single message. There was however, one victim, who managed to receive ten Emotet attack messages during that same period. Either Emotet has something against that guy in particular, or more likely, it is simply an artifact about the method Emotet uses to distribute victim email addresses to its outbound spam emitters.

A word about passwords

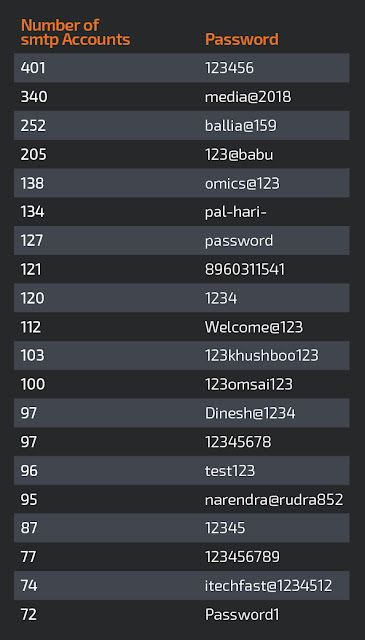

Emotet's stolen outbound email credentials contained over 176,000 unique passwords, so we decided to have a look at the passwords by themselves, without regard to the username or mail server IP. Below is a list of the most common passwords, and on the left hand side is the number of unique outbound SMTP credentials found utilizing that particular password.

It comes as no surprise that perennially problematic passwords such as "123456" and "password" (along with numerous variations of those) appear with a significant degree of prominence. However, there are other passwords in the set that are much more unique in terms of "Why would so many different accounts use that same strange password?" Most likely these are victims of Emotet who themselves controlled a large number of distinct email boxes while also committing the cybersecurity cardinal sin of reusing the same password across many different accounts.

Conclusion

Emotet has been around for years, this reemergence comes as no surprise. The good news is, the same advice for staying protected from Emotet remains. To avoid Emotet taking advantage of your email account, be sure to use strong passwords and opt in to multi-factor authentication, if your email provider offers that as an option. Be wary of emails that seem to be unexpected replies to old threads, emails that seem suspiciously out of context, or those messages that come from familiar names but unfamiliar email addresses. As always, you can rely on Snort rules to keep your system and network protected, as well. Previous Snort rules Talos has released will still protect from this wave of Emotet, and there is always the opportunity for new coverage in the future.

This is also a good opportunity to recognize that security researchers and practitioners can never take their foot off the gas. When a threat group goes silent, it's unlikely they'll be gone forever. Rather, this opens up the opportunity for a threat group to return with new IOCs, tactics, techniques and procedures or new malware variants that can avoid existing detection. Just as we saw earlier this year with the alleged breakup of the threat actors behind Gandcrab, it's never safe to assume a threat is gone for good.

IoCs

Indicators of compromise related to Emotet's latest activity can be found here.

Coverage

Additional ways our customers can detect and block this threat are listed below.

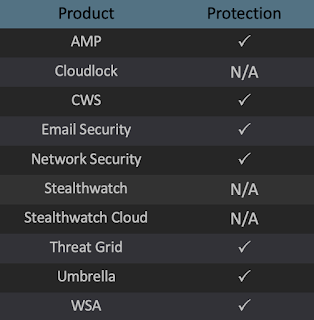

Advanced Malware Protection (AMP) is ideally suited to prevent the execution of the malware used by these threat actors.

Cisco Cloud Web Security (CWS) or Web Security Appliance (WSA) web scanning prevents access to malicious websites and detects malware used in these attacks.

Email Security can block malicious emails sent by threat actors as part of their campaign.

Network Security appliances such as Next-Generation Firewall (NGFW), Next-Generation Intrusion Prevention System (NGIPS), andMeraki MX can detect malicious activity associated with this threat.

AMP Threat Grid helps identify malicious binaries and build protection into all Cisco Security products.

Umbrella, our secure internet gateway (SIG), blocks users from connecting to malicious domains, IPs, and URLs, whether users are on or off the corporate network.

Open Source Snort Subscriber Rule Set customers can stay up to date by downloading the latest rule pack available for purchase on Snort.org.