By Vitor Ventura with contributions from Chris Neal.

Executive summary

The Gustuff banking trojan is back with new features, months after initially appearing targeting financial institutions in Australia. Cisco Talos first reported on Gustuff in April. Soon after, the actors behind Gustuff started by changing the distribution hosts and later disabled its command and control (C2) infrastructure. The actor retained control of their malware since there is a secondary admin channel based on SMS.

The latest version of Gustuff no longer contains hardcoded package names, which dramatically lowers the static footprint when compared to previous versions. On the capability side, the addition of a "poor man scripting engine" based on JavaScript provides the operator with the ability to execute scripts while using its own internal commands backed by the power of JavaScript language. This is something that is very innovative in the Android malware space.

The first version of Gustuff that we analyzed was clearly based on Marcher, another banking trojan that's been active for several years. Now, Gustuff has lost some similarities from Marcher, displaying changes in its methodology after infection..

Today, Gustuff still relies primarily on malicious SMS messages to infect users, mainly targeting users in Australia. Although Gustuff has evolved, the best defense remains token-based two-factor authentication, such as Cisco Duo, combined with security awareness and the use of only official app stores.

Campaigns

After Talos' initial report, the Gustuff operators changed their deployment redirections. When those were blocklisted, the actors eventually disabled the C2, but they never totally stopped operations. Several samples were still around, but the hardcoded C2 was not available. A new campaign was detected around June 2019, there were no significant changes the malware. The campaign was using Instagram, rather than Facebook, to lure users into downloading and installing malware.

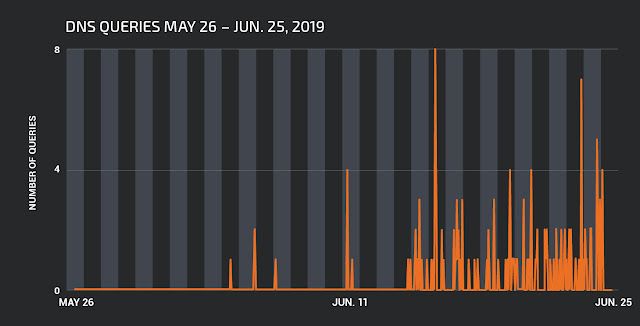

Domain hits in June

The Instagram-related domains are used for the initial infection, using the exact same method of operation as before.

But a new campaign spun up at the beginning of this month, this time with an updated version of the malware. Just like in the previous version, any target that would be of no use as a potential target is still used to send propagation SMS messages. Each target is requested to send SMSs at a rate of 300 per hour. Even though the rate will be limited to the mobile plan of each target, this is an aggressive ask.

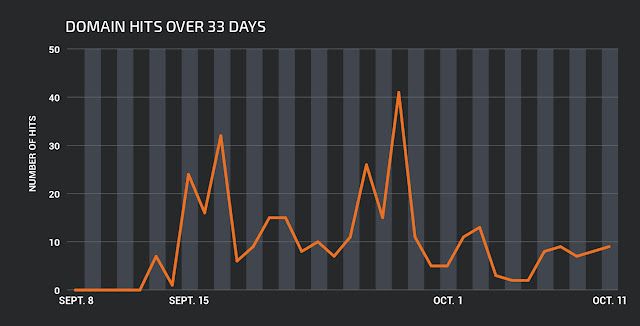

Domain hits in October

This method of propagation has a low footprint, since it uses SMS alone, but it doesn't seem to be particularly effective, given the low number of hits we've seen on the malware-hosting domains.

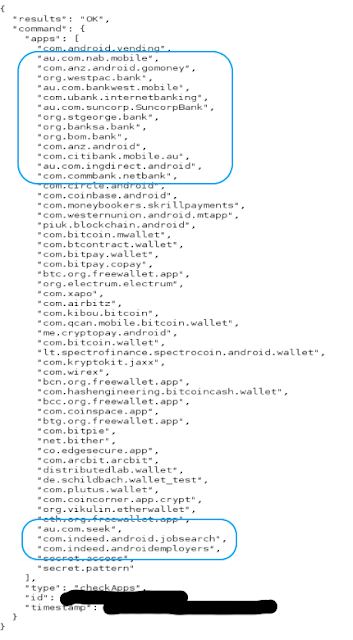

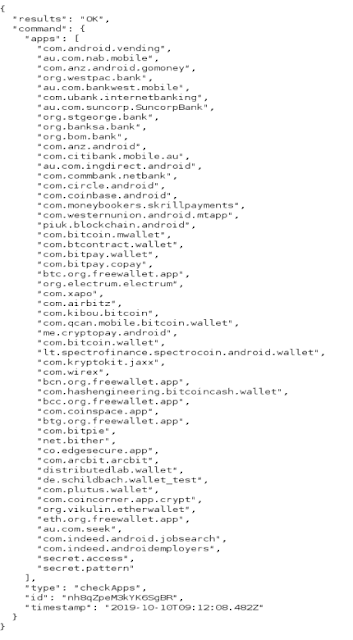

Targeted applications

Just as before, this campaign mainly targets Australian banks and digital currency wallets. This new version seems to target hiring sites' mobile apps.

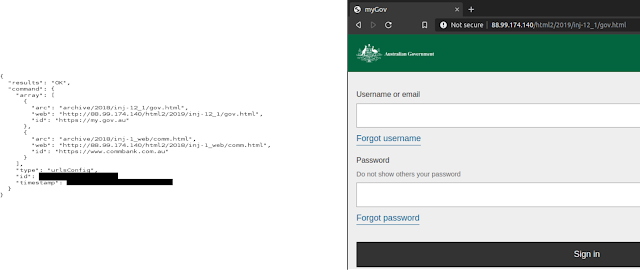

One of Gustuff's capabilities is the dynamic loading of webviews. It can receive a command to create a webview targeting specific domains, while fetching the necessary injections from a remote server.

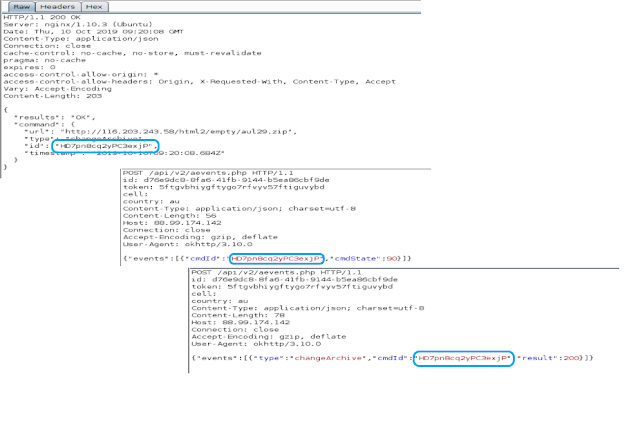

Request Result During our investigation, we received a command from the C2 to target the Australian Government Portal that hosts several public services, such as taxes and social security. The command was issued before the local injections were loaded (using the changearchive command). The injections were loaded from one of the C2 infrastructure servers. This command is not part of the standard activation cycle and was not part of the injections loaded by the version we analyzed in April.

This represents a change for the actor, who now appears to be targeting credentials used on the official Australian government's web portal.

Technical analysis

This new version of Gustuff seems to be another step in its planned evolution. This malware is still deployed using the same packer, but

there are several changes in the activity cycle, which take advantage of functionalities which either where already there or where being prepared. One of the changes in the behaviour is the state persistency across installations.

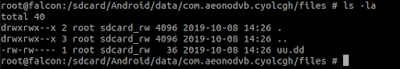

ID file

During the activation process, the malware attempts to create a file called "uu.dd" in the external storage. If the file exists, it will read the UUID value stored inside it that will be used as an ID for the C2. When this happens, the malware won't go through all the activation process. Instead, it will receive commands from the C2 immediately. This file already existed in previous versions. However, the behaviour described above was never observed.

The main API follows the same philosophy. Gustuff pings the C2 at a predetermined interval, which will either reply with an "ok" or it will issue the command to be executed.

The targeted applications are no longer hardcoded in the sample. They are now provided to the malware during the activation cycle using the command "checkApps." This command already existed on the previous version, but its usage during the activation cycle was not mandatory.

checkApps Command

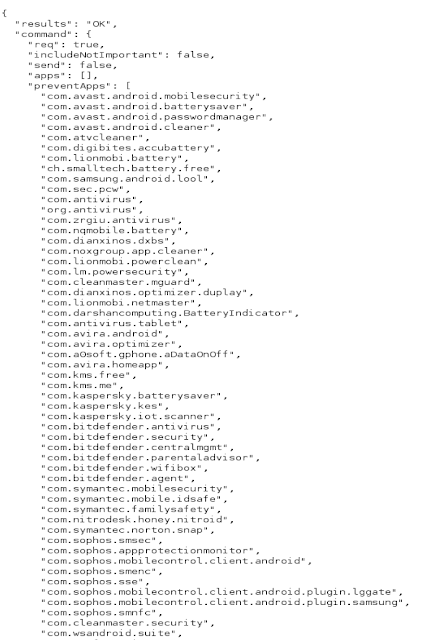

The list of anti-virus/anti-malware software that Gustuff blocks as a self-defense mechanism is now also loaded during the activation cycle.

Example of applications is blocks (not full list)

These changes in the Gustuff activation cycle indicate that the actor decided to lower the malware static analysis footprint by removing the hard-coded lists. Both commands already existed in the communication protocol and could have been used in runtime.

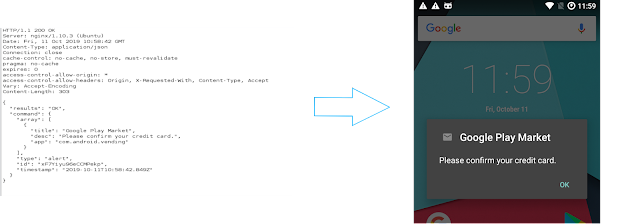

Command Result

During the activation cycle, the malware now asks the user to update their credit card information. The difference is that it does not immediately show a panel for the user to provide the information. Instead, it will wait for the user to do it and — leveraging the Android Accessibility API — will harvest it. This method of luring the victim to give up their credit card information is less obvious, increasing the chances of success, even if it takes longer.

The communication protocol now has a secondary command execution control. Each command is issued with a unique ID, which is then used by Gustuff to report on the command execution state.

Command execution control This allows the malicious actor to know exactly in which state the execution is, while before, it would only know if the command was received and its result. This new control mechanism also generated the asynchronous command capability. The malware operator can now issue asynchronous commands that will receive feedback on its execution while performing other tasks — "uploadAllPhotos" and "uploadFile" commands are two of such commands.

With these changes, the malicious actor is obtaining better control over the malware while reducing its footprint.

This version of Gustuff has substantial changes in the way it interacts with the device. The commands related to the socks server/proxy have been removed, as have all code related to its operation. This functionality allowed the malicious operator to access the device and perform actions on the device's UI. We believe this is how the malicious actor would perform its malicious activities. We believe that after collecting the credentials, using the webviews, the actor would use this connection to interactively perform actions on the banking applications.

This functionality is now performed using the command "interactive," which will use the accessibility API to interact with the UI of the banking applications. This method is less "noisy" on the network, since it takes advantage of the C2 connection, rather than creating new connections.

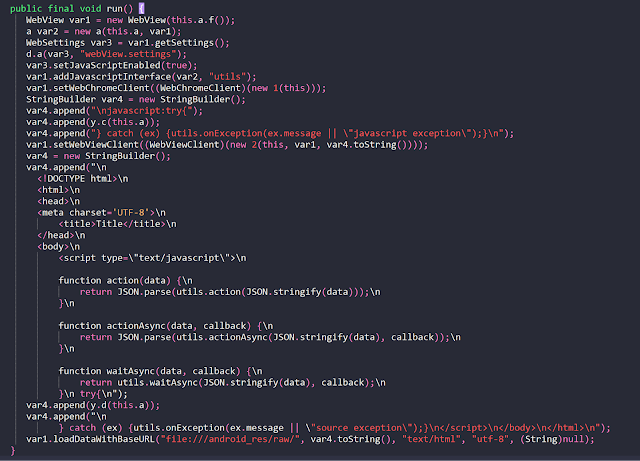

The command "script" is also new. This is a very simple command with huge potential. Gustuff starts a WebChromeClient with JavaScript enabled. Afterward, it adds a JavaScript interface to the webview, which will allow the execution of methods defined in the malware code.

JavaScript scripting

By default, the WebView object already has access to the filesystem, which is not an additional security risk in this context, allows the operator perform all kinds of scripts to automate its tasks, especially when the script also has access to commands from the application.

Conclusion

This is an evolving threat, and the actor behind it seems to want to press on, no matter the level of coverage this campaign gets. Instead, they changed the malware code to have a lower detection footprint on static analysis, especially after being unpacked. Although there are no changes in the way it conducts the campaign, Gustuff still changed the way it uses the malware to perform its fraudulent activities. The main target continues to be banking and cryptocurrency wallets. However, based on the apps list and code changes, it is safe to assume that the actor behind it is looking for other uses of the malware.

Coverage

Snort SID: 51908-51922

Additional ways our customers can detect and block this threat are listed below.

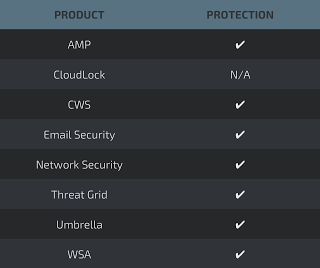

Advanced Malware Protection (AMP) is ideally suited to prevent the execution of the malware used by these threat actors. Exploit Prevention present within AMP is designed to protect customers from unknown attacks such as this automatically.

Cisco Cloud Web Security (CWS) or Web Security Appliance (WSA) web scanning prevents access to malicious websites and detects malware used in these attacks.

Email Security can block malicious emails sent by threat actors as part of their campaign.

Network Security appliances such as Next-Generation Firewall (NGFW), Next-Generation Intrusion Prevention System (NGIPS), and Meraki MX can detect malicious activity associated with this threat.

AMP Threat Grid helps identify malicious binaries and build protection into all Cisco Security products.

Umbrella, our secure internet gateway (SIG), blocks users from connecting to malicious domains, IPs, and URLs, whether users are on or off the corporate network.

Open Source Snort Subscriber Rule Set customers can stay up to date by downloading the latest rule pack available for purchase on Snort.org.