By Nick Biasini, Edmund Brumaghin, and Jaeson Schultz.

Emotet is one of the most heavily distributed malware families today. Cisco Talos observes large quantities of Emotet emails being sent to individuals and organizations around the world on an almost daily basis. These emails are typically sent automatically by previously infected systems attempting to infect new systems with Emotet to continue growing the size of the botnets associated with this threat. Emotet is often the initial malware that is delivered as part of a multi-stage infection process and is not targeted in nature. Emotet has impacted systems in virtually every country on the planet over the past several years and often leads to high impact security incidents as the network access it provides to adversaries enables further attacks, such as big-game hunting and double-extortion ransomware attacks.

Cisco Talos obtained ownership of several domains that Emotet uses to send SMTP communications. We leveraged these domains to sinkhole email communications originating from the Emotet botnets for the purposes of observing the characteristics of these email campaigns over time and to gain additional insight into the scope and profile of Emotet infections and the organizations being impacted by this threat. Emotet has been observed taking extended breaks over the past few years, and 2020 was no exception. Let's take a look at what Emotet has been up to in 2020 and the effect it's had on the internet as a whole.

Emotet background

Emotet began its life as a banking trojan, but over the years, it evolved into what can now be classified as a highly modular threat that adversaries leverage for a variety of purposes. In recent years, it has often been used as a "beachhead" in victim networks as it provides initial access and long-term persistence that malicious adversaries can use to conduct further intrusion activities from within infected networks. In many cases, it is used as the initial payload in a multi-stage infection process and can be operational in victim networks for extended periods of time before adversaries choose to leverage the access it provides to further attack organization. This is an important consideration for network defenders as system backups may be compromised as a result of long-term infections that reside in systems in the environment.

There are several other malware families that are also often delivered alongside Emotet such as Trickbot, Qakbot and others. Many network-based ransomware incidents, such as those conducted by the operators of Ryuk ransomware, can be traced back to initial network access gained via Emotet. Over the past few years, Emotet has periodically taken breaks from sending spam messages, with periods of inactivity ranging from weeks to months in several cases. It is important to note that while these periods of inactivity correspond to lack of spam distribution, the botnets are typically still operational during these periods and as such, previously infected systems can still be leveraged for intrusions.

Organizations and network defenders should be aware of the threat posed by Emotet and ensure that they have strategies in place to prevent compromise, detect infections within their environments, and ensure that their backup and recovery strategies compensate for situations in which the malware may have been resident for extended periods prior to discovery.

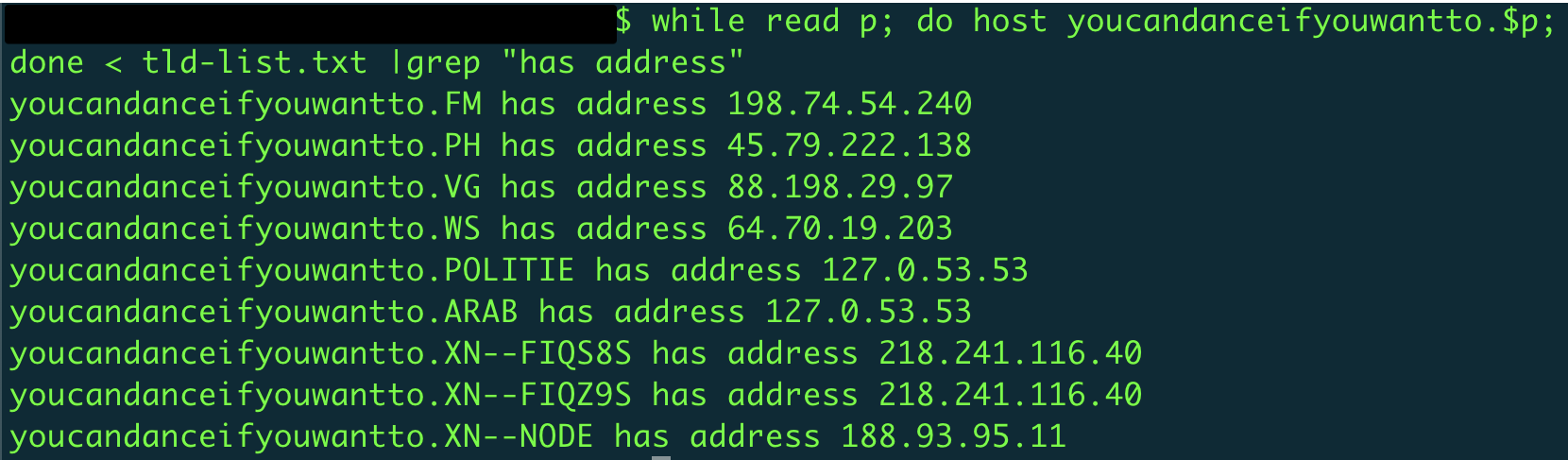

Sinkholing Emotet SMTP domains

Several top-level domains (TLDs) that are widely used across the internet exhibit interesting behavior when Domain Name System (DNS) resolution is attempted for domains that do not exist or are not actively registered. In many cases, the TLDs are configured to resolve non-existent domains to a specific IP address. Whenever the name servers associated with these TLDs receive resolution requests from clients on the internet for domains that are not actively configured to resolve to a specific IP address, they respond with a default IP address value, regardless of whether the domain being queried is invalid or has ever existed. Upon discovering this behavior, we leveraged the official list of TLDs available from ICANN to determine which TLDs operate in this manner. We built a list of TLDs that exhibit the aforementioned behavior by rotating through this list of TLDs and requesting name resolution for domains that do not exist.

The table below lists the affected TLDs that we discovered, as well as the IP address that the nameservers return when the requested domain is either non-existent or not otherwise configured for name resolution.

This DNS behavior allows researchers to leverage technologies like Passive DNS (pDNS) to identify domains that may have been valid at one point but are no longer actively registered and maintained. It also enables identification and tracking of the volume of name resolution requests for these invalid domains being performed by various clients across the internet. This is useful for identifying domains that were previously part of domain generation algorithms (DGAs) or otherwise used for various malware operations like command and control (C2).

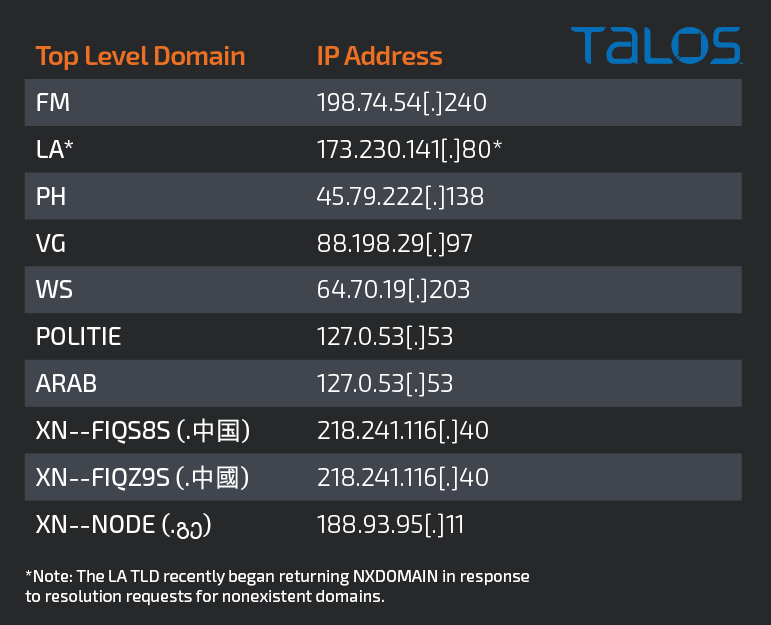

For example, the name resolution activity for a C2 domain previously associated with Phorpiex that has since been abandoned, is shown below. While the adversary no longer controls the domain, orphaned bots are still continuing to reach out to it, attempting to establish a C2 channel. Note that it currently resolves to the default IP address returned for nonexistent domains in the WS TLD as previously described earlier in this section.

During our analysis of various orphaned domains, we discovered many domains that were used previously for C2 by systems infected with a variety of threats like Dyre, Necurs, StealthWorker, and others. While many of the domains we investigated were part of time-based DGAs and not particularly useful, we identified several domains previously associated with SMTP servers that systems infected with Emotet use to relay malicious spam messages. We obtained ownership of these domains and began sinkholing SMTP communications originating from these infected systems.

Sinkholing is the process of redirecting this malicious botnet traffic away from its intended source and into a harmless destination. This has provided visibility into hundreds of thousands of Emotet emails each month. It has also allowed us to determine the scope of the systems sending malicious spam, profile the geographic and industry makeup of these systems, and identify organizations suffering from resident Emotet infections.

Emotet activity in 2020

Emotet spent the early part of 2020 churning out large quantities of malicious email in volumes consistent with what has been observed from this threat in recent years. As the COVID-19 pandemic began to spread across the globe, malware distributors took advantage of the public's focus on this emerging crisis — and Emotet was no exception. The use of current events in phishing and malspam lures is not a new technique and has been observed being used by various threat actors as described in detail here.

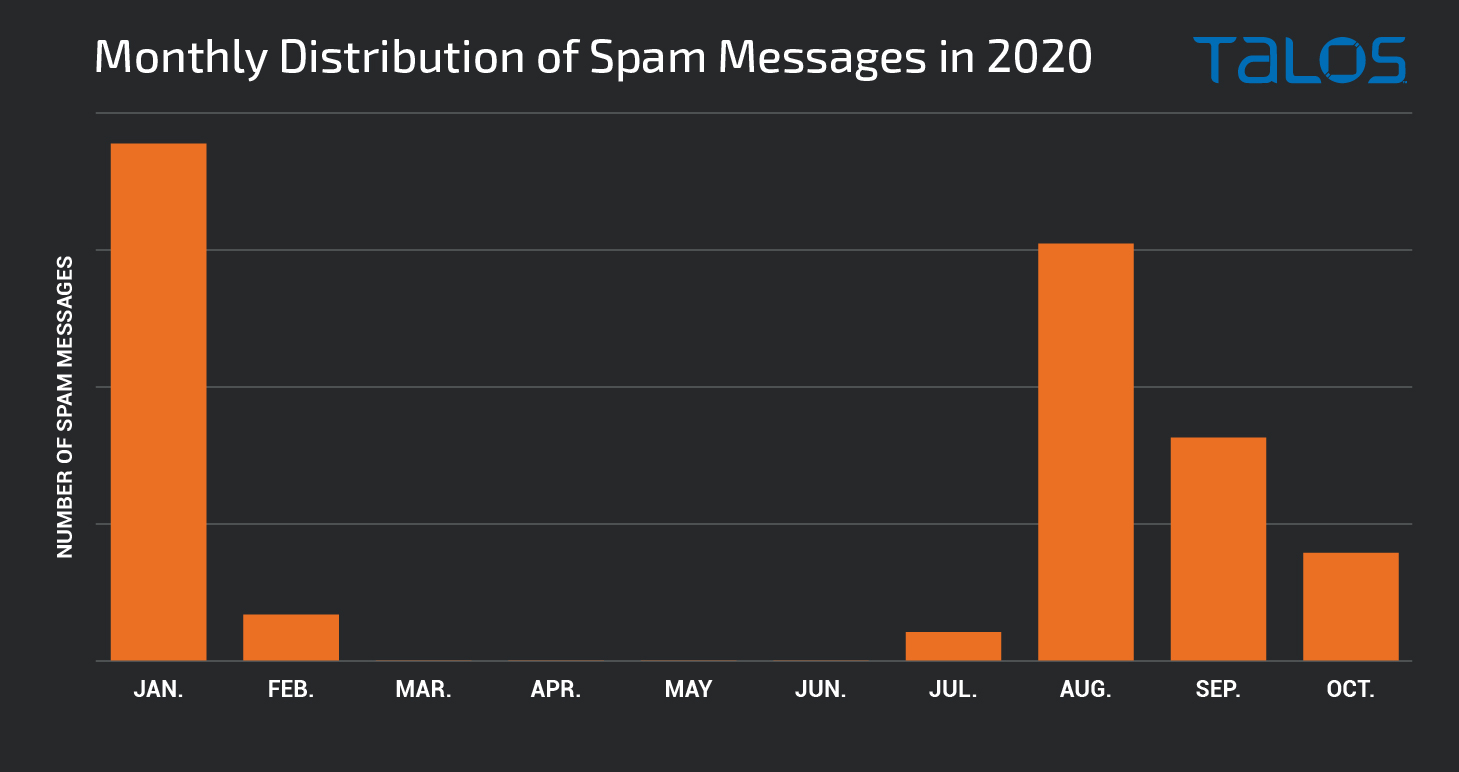

Emotet occasionally takes periodic breaks from sending malicious spam emails, as seen earlier this year. Starting in February 2020, Emotet took an extended break from spamming, with low volumes of Emotet spam emails being observed for a period of several months. It spun up again in June with massive amounts of spam being sent starting in July and continuing through to the present time, with intermittent pauses along the way. The following graph graph shows the relative volumes of spam for each month in 2020.

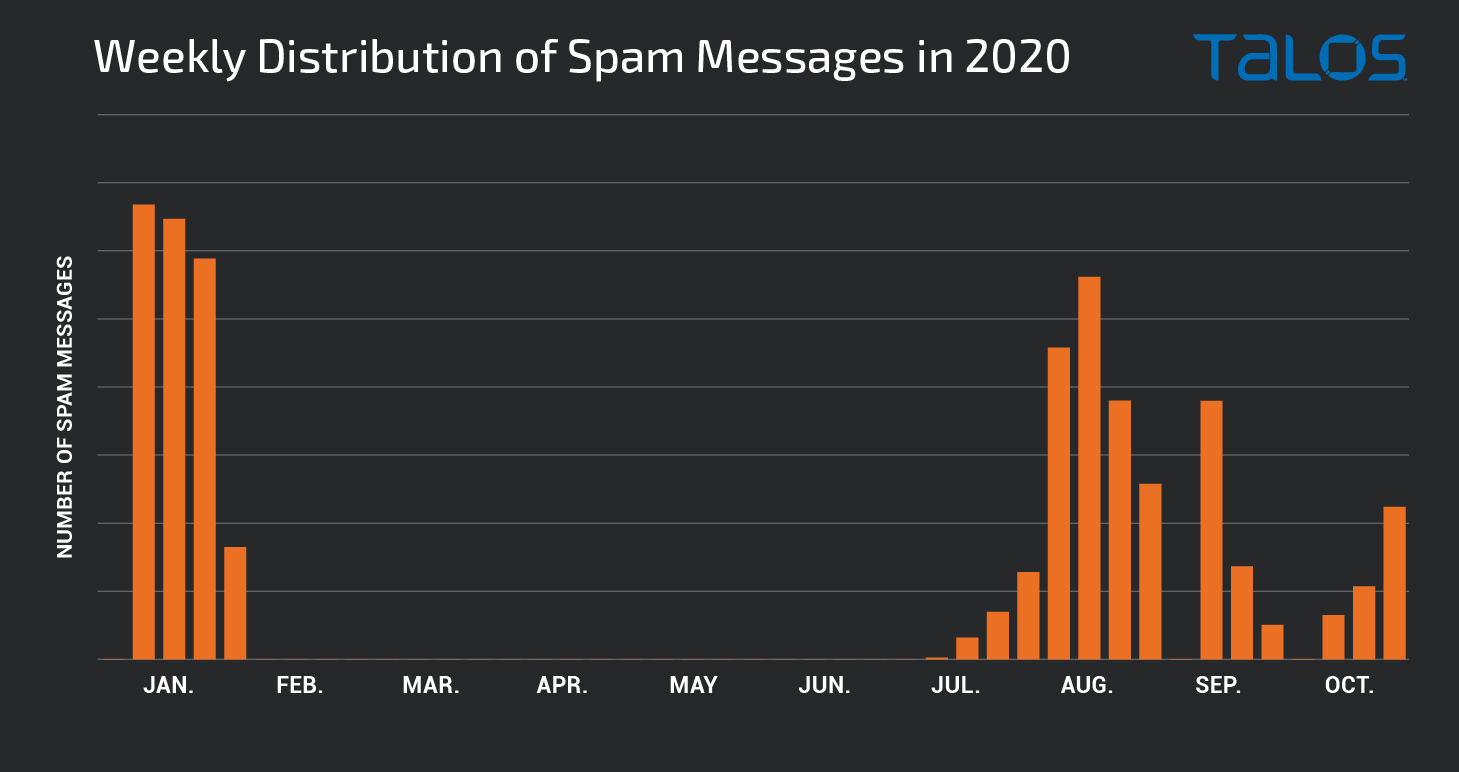

A further breakdown shows the volume of spam emails generated by the Emotet botnets on a weekly basis throughout the course of 2020.

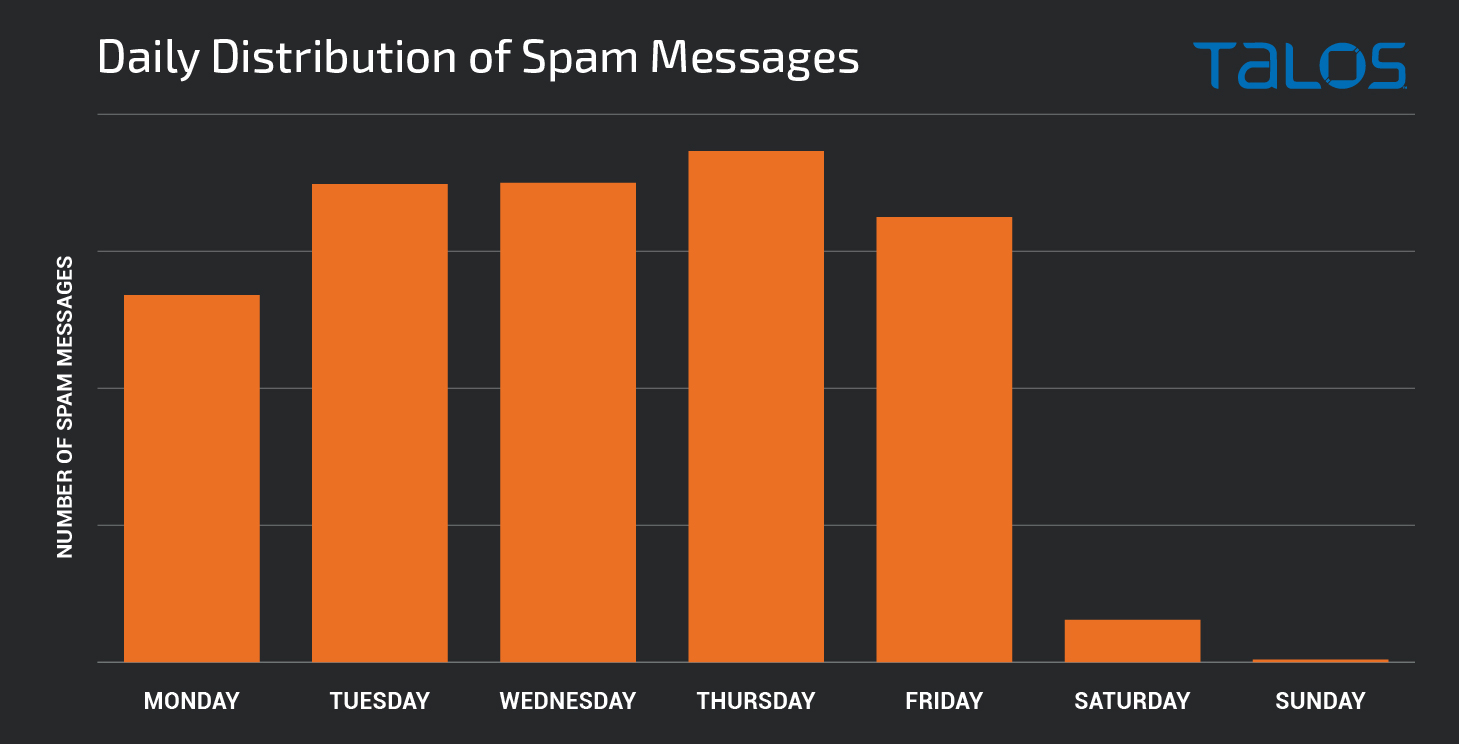

We also performed an analysis of the email data that was transmitted by systems infected with Emotet to get a better understanding of the characteristics of these spam runs and the emails themselves. One thing that is immediately noticeable is the fact that hardly any spam messages are sent on weekends.

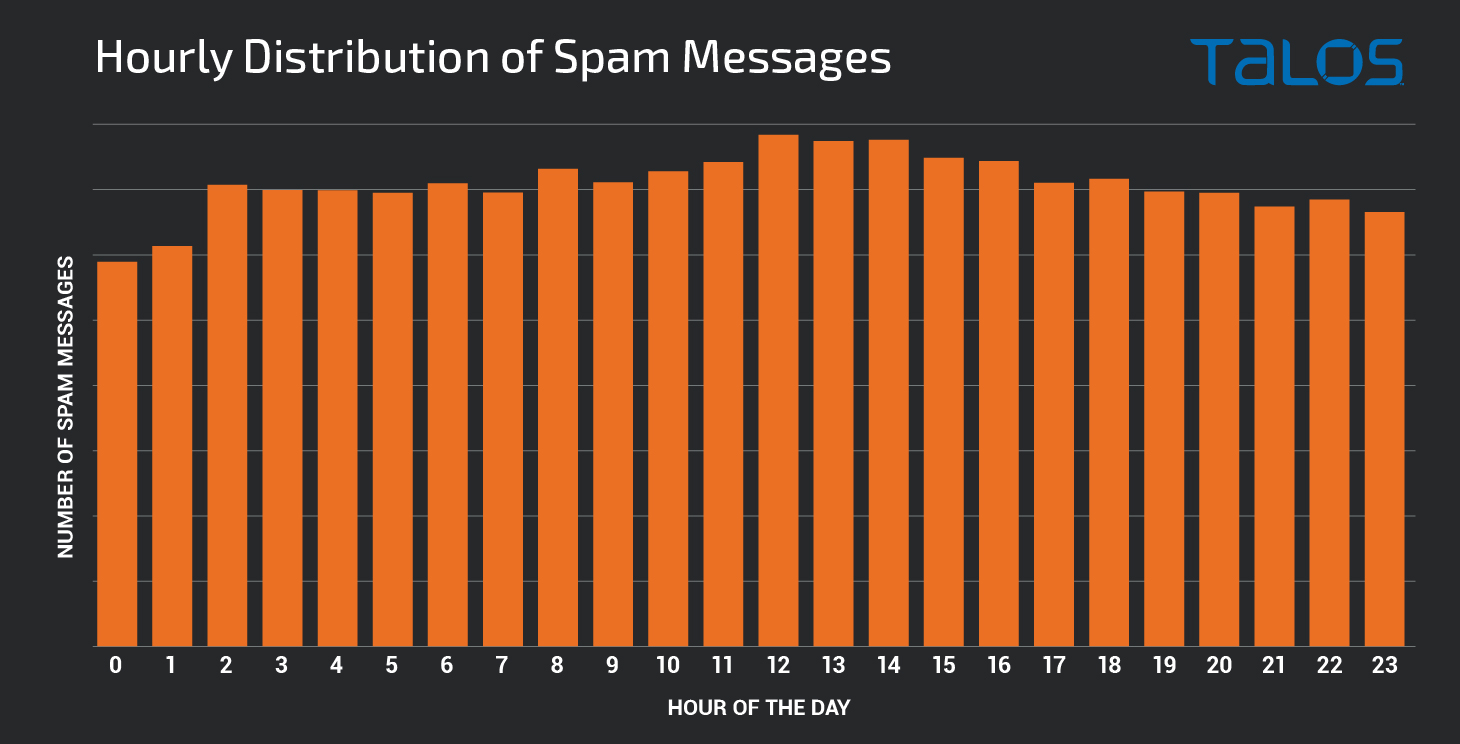

Interestingly enough, when the botnets are spamming, they are doing so consistently around the clock. The chart below shows the distribution of messages received broken down by the hour of the day in which the transmission occurred. This shows the consistency with which the messages are transmitted on an hourly basis.

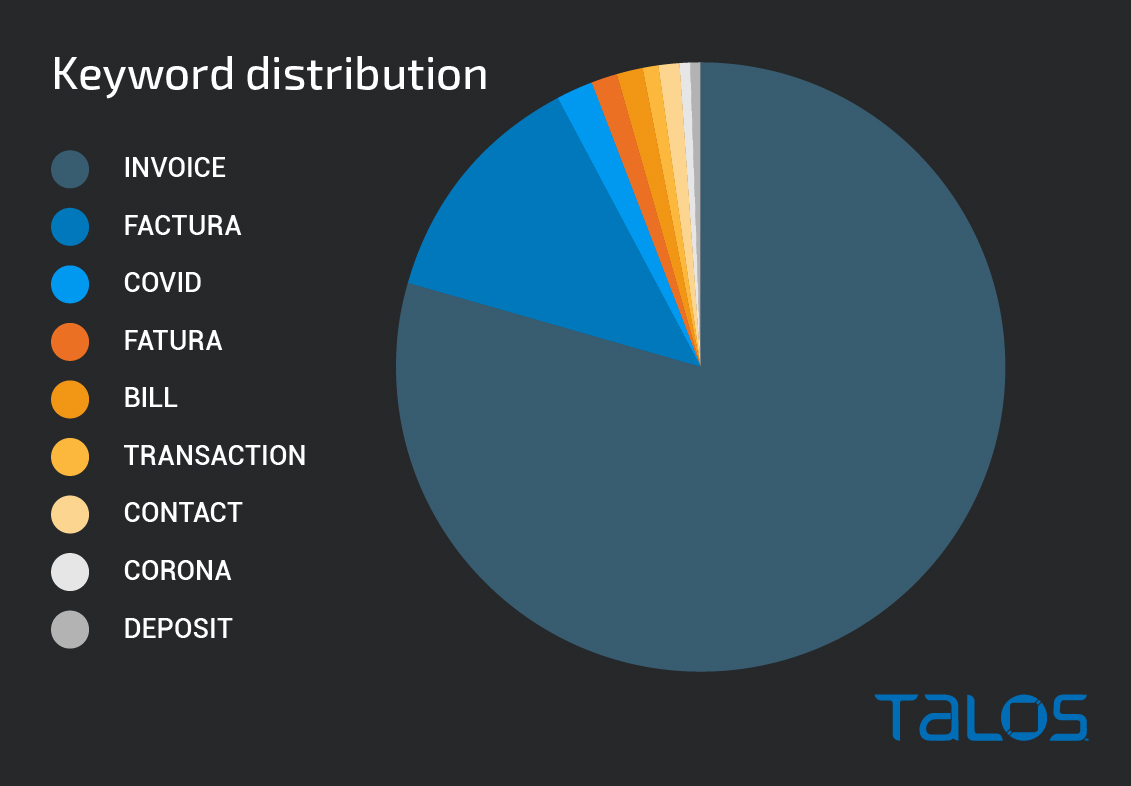

We identified several interesting characteristics associated with these campaigns. Analysis of the subject lines of messages sent by infected systems uncovered several keywords that are used extensively across the different distribution campaigns we observed. The use of "invoice" as a keyword across emails was the most common by an extremely high margin, consistent with what is a commonly observed theme to many malspam campaigns seen across the threat landscape.

When looking at the top five subjects by volume, a Japanese language subject was found: "会議開催通知," which translates to "Meeting Notification." Typically, we find that the most voluminous subjects use Western languages, finding a Japanese example that high on the list was unexpected. In general, Japanese and Korean, although a small percentage, were the most common non-Western languages we observed while analyzing this data.

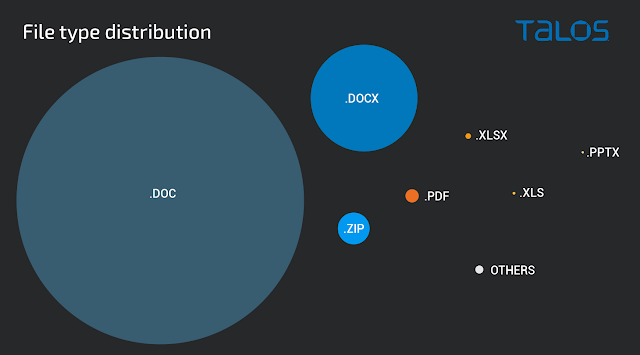

Most of the emails associated with Emotet feature the use of malicious attachments that function as malware downloaders. Opening the attached files and enabling the malicious contents causes them to reach out to the attacker's distribution infrastructure to download additional malicious content that is then executed on the victim's system, thus infecting it with malware. The overwhelming majority of attachments leverage malicious Microsoft Office documents (i.e. DOC, DOCX, XLS, XLSX) however Emotet malspam has also been observed featuring ZIP archives, PDFs, and more. Below is a chart showing the distribution of attachments by file type based on telemetry data collected over the past twelve months.

There is one other type of email attachment we have seen in campaigns, although not widespread, encrypted or password protected files. We found a small amount of these types of campaigns and they are typically used in conjunction with stolen email threads. One thing to note for these is instead of using basic or simple passwords they include relatively complex passwords, which is uncharacteristic for password protected malicious attachments.

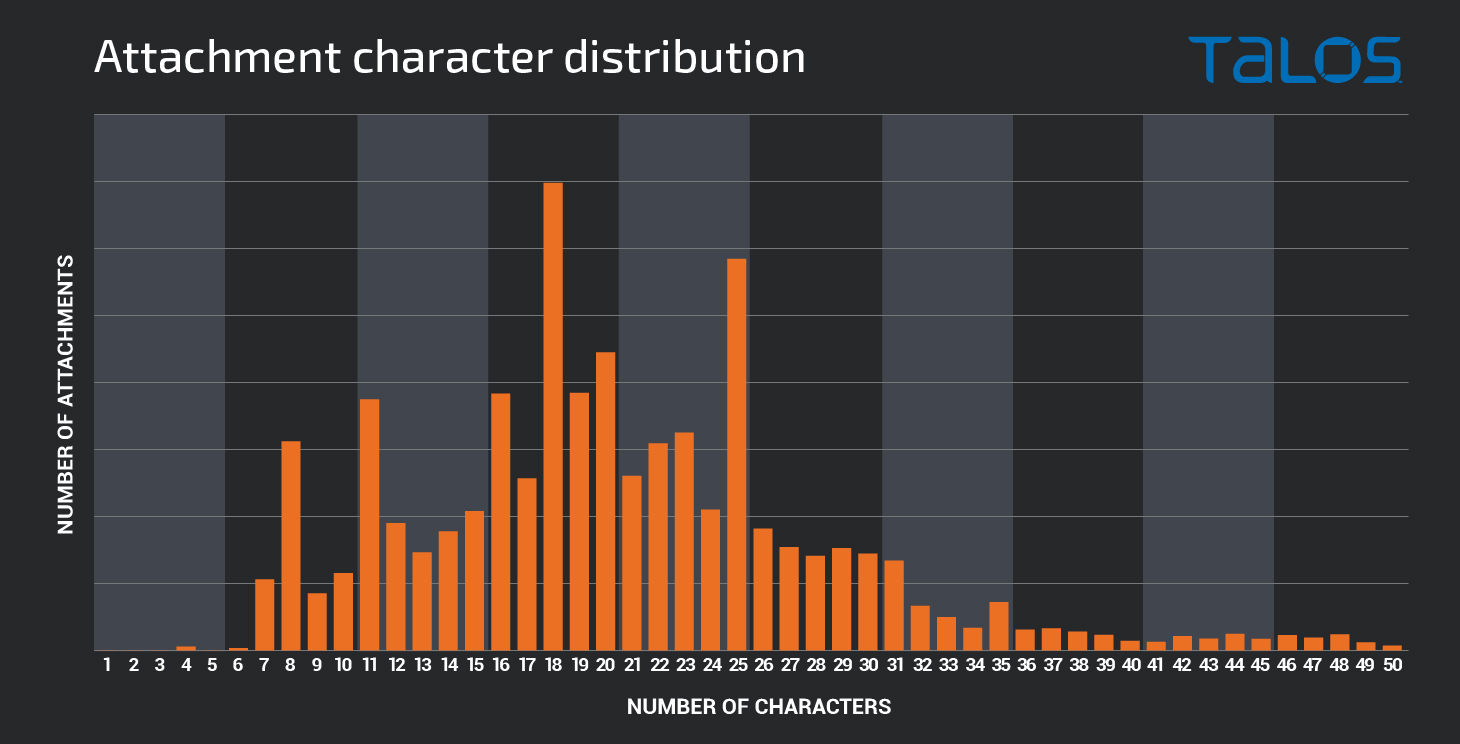

Investigating the character count distribution associated with malicious attachment filenames shows that there is a wide range in terms of the approximate length of filenames associated with Emotet malspam, with the most common file names used being 18 characters in length (including the file extension).

Emotet has also been observed distributing emails containing hyperlinks that, when clicked by potential victims, directs their system to reach out to the attacker's distribution servers to obtain malicious content to execute, resulting in malware infection. In most cases, these distribution servers are running WordPress, a content management system (CMS) that is frequently abused by attackers and used to host malicious components which are used in malware infections. In many cases, the servers used for distribution were running outdated plugins, themes, etc., making them attractive targets for compromise.

Profiling infected systems

While Emotet is often referred to as a singular threat, it is actually composed of multiple distinct botnets, which are referred to by the security research community as "epochs." At present, there are three epochs, each with distinct supporting infrastructure for various malware operations like C2. In analyzing the SMTP sinkhole data we collected, we identified infected systems from each of these three botnets attempting to transmit malicious spam using our newly acquired domains.

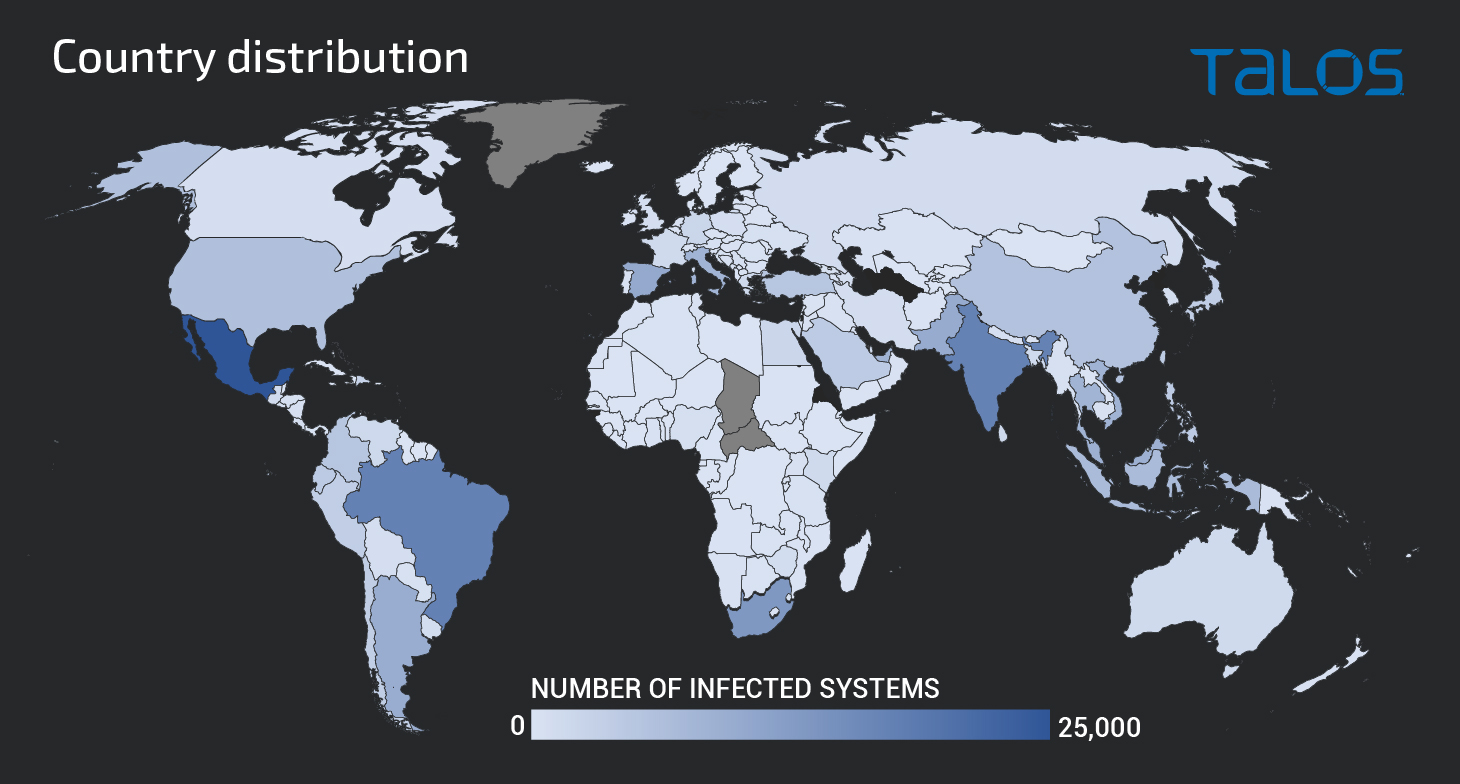

We identified infected systems located in more than 200 different countries. This highlights how widespread Emotet's reach is, affecting virtually every country in the world. Below is a map showing the geographic regions associated with the largest number of infected systems that we observed.

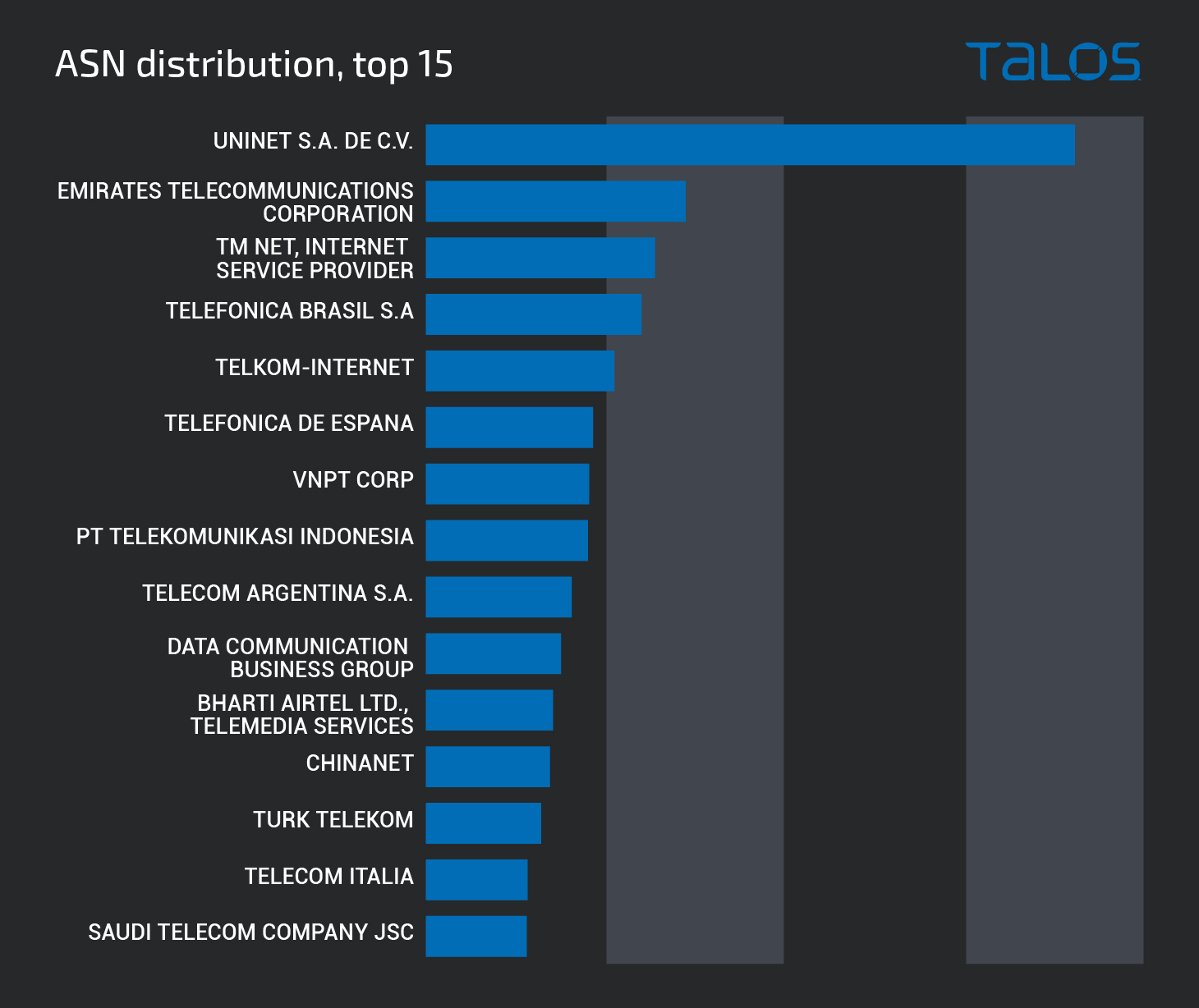

We also analyzed the network providers associated with these infected systems to determine what ISPs were most commonly affected. The graph below shows the top ASNs we observed sending malspam.

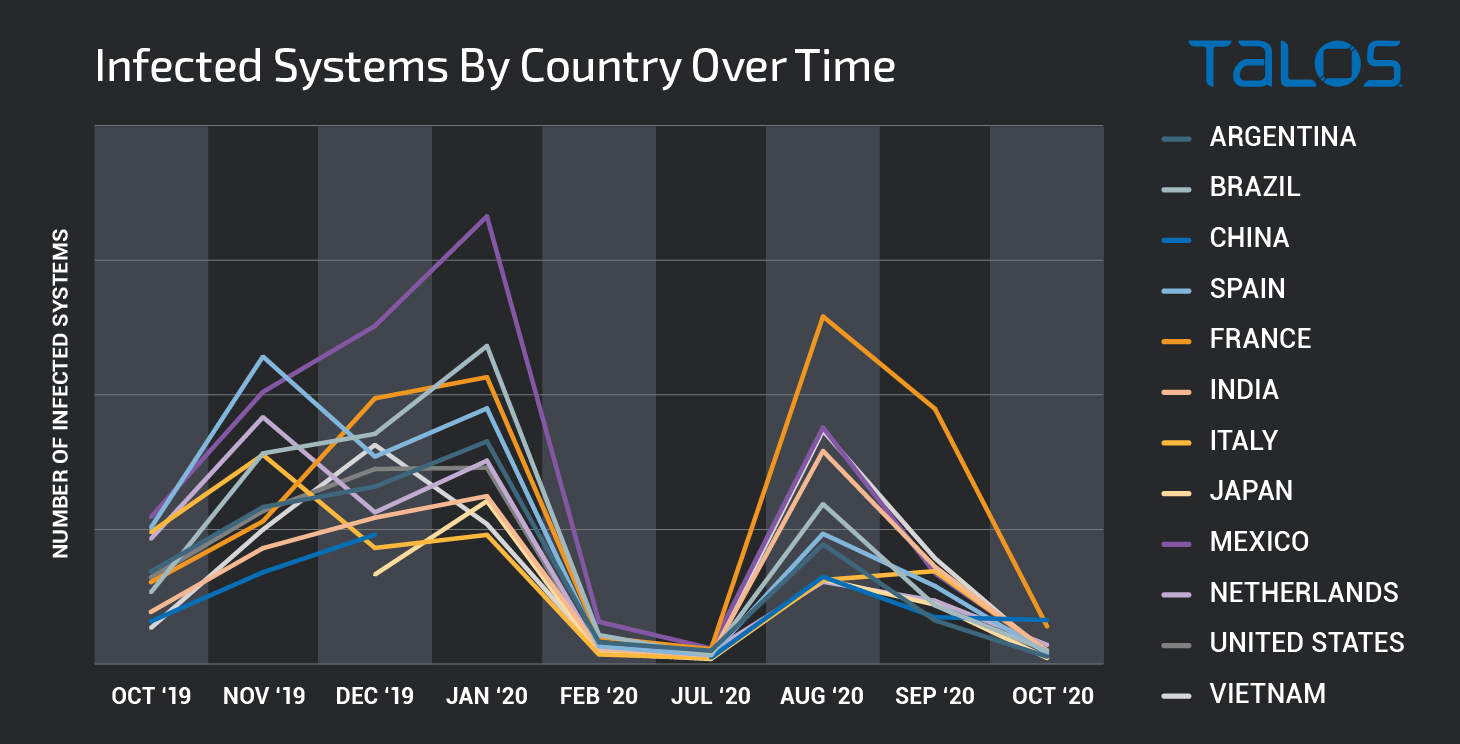

It is important to note that the distribution of systems infected by Emotet is constantly changing, as existing infections are removed and new ones are added. We analyzed the botnet distribution over the course of the past twelve months and tracked these changes over time. This long term geographic distribution over time can be seen in the graph below.

Emotet is a heavily distributed threat that has wide-ranging impacts on a variety of different industries and geographic regions. Malicious activity associated with this threat has continued throughout 2020 and will likely continue for the foreseeable future.

Conclusion

Emotet is a constantly evolving threat that poses risks to organizations all over the world. Large volumes of malicious spam emails generated by systems infected with Emotet are constantly being sent in an attempt to infect additional systems and provide persistent network access that can be used for a variety of nefarious purposes. Organizations should be aware of this threat as it continues to change over time and ensure that they have strategies in place to protect their environment from the impacts of successful infection. In many cases, Emotet is the initial stage of a multi-stage infection process that often features use of additional malware payloads. Since Emotet can be present in environments for extended periods of time prior to discovery by security teams, it is essential that organizations develop comprehensive backup and recovery strategies that can compensate for these situations prior to an incident occurring. This approach to cybercrime continues to be lucrative for cybercriminals and as such is likely not going away in the foreseeable future. Cisco Talos will continue to monitor this threat to ensure that customers remain protected as it continues to change and evolve over time.

Coverage

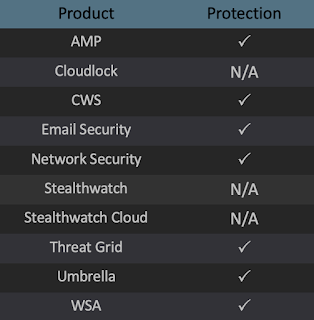

Ways our customers can detect and block this threat are listed below.

Advanced Malware Protection (AMP) is ideally suited to prevent the execution of the malware detailed in this post. Below is a screenshot showing how AMP can protect customers from this threat. Try AMP for free here.

Cisco Cloud Web Security (CWS) or Web Security Appliance (WSA) web scanning prevents access to malicious websites and detects malware used in these attacks.

Email Security can block malicious emails sent by threat actors as part of their campaign.

Network Security appliances such as Next-Generation Firewall (NGFW), Next-Generation Intrusion Prevention System (NGIPS), and Meraki MX can detect malicious activity associated with this threat.

Threat Grid helps identify malicious binaries and build protection into all Cisco Security products.

Umbrella, our secure internet gateway (SIG), blocks users from connecting to malicious domains, IPs and URLs, whether users are on or off the corporate network.

Additional protections with context to your specific environment and threat data are available from the Firepower Management Center.