Internet technology evolves rapidly, and the World Wide Web (WWW or Web) is currently experiencing a transition into what many are calling "Web 3.0". Web 3.0 is a nebulous term. If you spend enough time Googling it, you'll find many interpretations regarding what Web 3.0 actually is. However, most people tend to agree that Web 3.0 is being driven by cryptocurrency, blockchain technology, decentralized applications and decentralized file storage.

Web 3.0 innovations include the immersive 3-D experience known as the "Metaverse," a virtual reality environment where people can explore, shop, play games, spend time with distant friends, attend a concert, or even hold a business meeting. The Metaverse is the next iteration of social media, and identity in the Metaverse is directly tied to the cryptocurrency wallet that used to connect. A user's cryptocurrency wallet holds all of their digital assets (collectables, cryptocurrency, etc.) and in-world progress. Since cryptocurrency already has over 300 million users globally, and a market capitalization well into the trillions, it's no wonder that cybercriminals are gravitating toward the Web 3.0 space.

Web 3.0 brings with it a host of unique challenges and security risks. Some Web 3.0 threats are simply fresh twists on old attacks — new ways of phishing, or social engineering designed to separate users from the contents of their cryptocurrency wallets. Other security problems are unique to the specific technology that powers Web 3.0, such as playing clever tricks with how data on the blockchain is stored and perceived.

How did we arrive at Web 3.0?

The web has become the largest and most valuable information resource in the world, but it didn't start out that way. For those of us lucky enough to connect to the original incarnation of the web (Web 1.0) during the 1990s, the landscape was replete with the sight of website hit counters, digging construction workers and orange construction cones. "This Website is under construction!" web pages were springing up everywhere.

By the early 2000s, the WWW was transitioning into "Web 2.0", which meant using the "Web as a platform." Inside Web 2.0, users interact with applications built on the web rather than applications residing inside their own desktop computer. This led to innovations such as social media apps, auction sites, blogs and other user-driven content-sharing websites. The technological advances that powered Web 2.0 have largely resulted in a landscape dominated by centralized applications, and built by large companies such as Facebook, Google and Amazon. The business models of many Web 2.0 companies are strikingly familiar: build a large audience of users, harvest information from or about those users, then sell that information for marketing and "other" purposes.

Of course, technology evolves, as does our personal relationship to it. Enter the new hotness: Web 3.0.

Web 3.0 is founded on the blockchain

One of the main technological advances driving the transition to Web 3.0 has been cryptocurrency and its underlying blockchain technology. A cryptocurrency blockchain functions as a distributed public ledger of all historical transactions. Armed with the hash of a transaction, or the address of a cryptocurrency wallet, anyone can examine any of the transactions that have previously occurred.

In addition to wallet addresses, you might find contract addresses belonging to "smart contracts." A smart contract is a computer program deployed on a blockchain. Once deployed, the program establishes an initial state. Users then interact with the program using transactions on the blockchain. For example, the Ethereum blockchain contains a built-in Turing-complete programming language, and that is where the majority of smart contracts are deployed today.

When smart contracts are deployed on the Ethereum blockchain, they are submitted as compiled code inside of a transaction. The compiled code can be referenced and decompiled back into readable source code, though many legitimate smart contracts go the extra mile and publish the source code for the smart contract publicly.

Any time anyone writes code, they are likely to make mistakes. This leads to bugs in the program. Sometimes a clever attacker can exploit these bugs to steal valuable information or carry out a cyber attack. In fact, some of the largest losses in the Web 3.0 space have come as a result of hackers who have exploited smart contract bugs.

Non-fungible tokens (NFTs) and permanence

Powered by smart contracts, NFTs (non-fungible tokens) are "tokens that we can use to represent ownership of unique items." For many metaverse projects, including Decentraland, and The Sandbox, NFTs represent items found in the metaverse or items that belong to a specific user. For example, a metaverse participant may have NFT clothing/accessories for their metaverse avatar, NFT event tickets, in-game assets for video games, and more. In fact, identity in the metaverse typically corresponds to the cryptocurrency wallet the user connects.

Fungibility refers to the ability to interchange an asset for another asset of the same type without losing any value. For example, a dollar bill is fungible – you can exchange any dollar in your wallet for any dollar in your friend's wallet, and you both still retain an asset that is worth exactly one dollar. By contrast, non-fungible assets are unique, and cannot be interchanged in the same way. An example of a non-fungible asset would be real estate. The value of a non fungible asset is based on the specifics and unique characteristics of that particular asset.

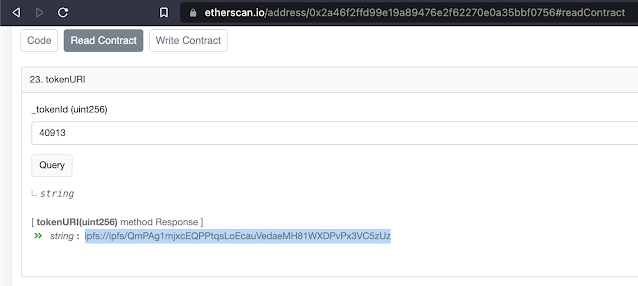

Because NFTs are recorded on the blockchain (which is itself a permanent record) there can be a certain feeling of permanence associated with NFTs. After all, it is impossible to go back into previously recorded blockchain transactions and alter the data of that transaction. Unfortunately the artwork for an NFT is typically not stored on the blockchain itself. Storing the actual content on the blockchain is prohibitively expensive in most cases, so most NFT creators do the next best thing and record metadata about the NFT on the blockchain. The metadata for a typical NFT includes things like information about the rarity/features of an NFT, a link to where the artwork from a project can be found.

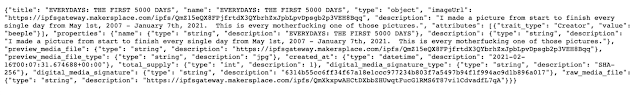

For example, Mike Winkelmann, the digital artist known as Beeple, recently sold an NFT of his work for $69 million at Christie's. When you look up the smart contract address for this NFT on Etherscan and plug in the specific NFT token ID, the result is an InterPlanetary Filesystem link for this NFT.

The InterPlanetary File System (IPFS) is a distributed file system protocol that utilizes a peer-to-peer network for storing and retrieving data. Files are referenced based on a hash of their contents. Nodes in the IPFS network can find and request a file corresponding to a specific content address from any node who has it, but to avoid being culled via garbage collection that file must be intentionally hosted (a.k.a. "pinned") by at least one IPFS node in the network.

Accessing that IPFS link will show us the contents of this NFT. Note that there are no graphics, only metadata.

The metadata includes a URL where anyone could find the image for this NFT. The URL for the NFT image is:

https://ipfsgateway.makersplace.com/ipfs/QmXkxpwAHCtDXbbZHUwqtFucG1RMS6T87vi1CdvadfL7qA

Rather than including a raw IPFS link, the URL for this NFT points to a standard web server, "makersplace.com". If anything happens to that domain — the web server goes down, the company goes out of business, etc. — it will negatively affect the hosting of this $69 million NFT.

In this specific case, the IPFS content hash, QmXkxpwAHCtDXbbZHUwqtFucG1RMS6T87vi1CdvadfL7qA, is contained in the path of the NFT URL. This hash could lead a motivated investigator to a different IPFS gateway, and eventually to the content that was intended to be linked. But there is nothing nothing in the ERC-721 NFT specification itself that provides for a hash or any other guarantees regarding what should rightfully appear at the link offered up in the NFT metadata. Additionally, many NFT smart contracts are set up so that the developers who created the contract can update NFT metadata at a later date. This includes the URL where the contents of the NFT can be found. For example, after people minted NFTs from the "Raccoon Secret Society" project, the project developers modified the URL for everyone's NFT to point to a pile of dead bones.

Fungible?

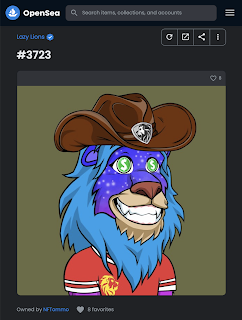

It turns out that NFTs aren't as "non-fungible" as people might want to believe. While it is true that once an NFT is minted, it's placed indelibly into the blockchain, nothing prevents copycats from taking the exact same artwork and minting it on a different blockchain or via a different smart contract on the exact same blockchain. Below, there's a real Lazy Lions project NFT, minted on the Ethereum blockchain and currently worth almost 2 ETH, along with a copycat, minted on the Polygon blockchain, and is essentially worthless.

Furthermore, it is not necessarily clear who owns the copyright to the underlying contents of an NFT. When you purchase an NFT, do you own just that narrow slice of metadata published on the blockchain, or do you own the rights to the NFT content itself? Already we have seen controversy over copyright claims to NFT projects. The problem is likely to get much worse, since once an NFT is placed on the blockchain, it can't be "taken down" and, oftentimes, the persons behind the NFT creation are only identifiable through mostly anonymous cryptocurrency wallet addresses.

Security concerns as we enter Web 3.0

All of this new Web 3.0 technology is fun and exciting, and mind-boggling amounts of money are being poured into the space. As a result, Web 3.0 has attracted the attention of developers, users, and cybercriminals alike. There are a few specific security issues that caught our attention with Web 3.0 outside of the inherent risks of getting involved with NFTs and cryptocurrency. If you're someone who is dabbling in Web 3.0 technology, what we discovered may serve as a warning that can help you safely and securely navigate the sometimes turbulent waters of the developing metaverse.

ENS domains: DNS for cryptocurrency wallets

One side effect of the transparency of public blockchains is the ability to inspect the contents of any wallet address. In Ethereum, wallet addresses are strings of 42 characters, such as: 0xce90a7949bb78892f159f428d0dc23a8e3584d75.

While anyone can look up the contents of a wallet address on the public ledger, it is rarely obvious who that wallet belongs to. Therefore, in a security-through-obscurity sort of way, most wallet addresses are somewhat anonymous. However, they are also nearly impossible to remember. Enter the Ethereum Name Service (ENS).

Like domain names such as cisco.com are a convenient shorthand for finding the IP address where Cisco lives on the internet, ENS domains attempt to provide a shorthand, easy to remember name which can be used to find the associated cryptocurrency wallet address.

For example, now you can register the ENS name yournamehere.eth and point it at a particular wallet address. Users of ENS-domain-aware apps can substitute the ENS name yournamehere.eth anywhere they would normally enter a wallet address. What has followed is reminiscent of the original domain name gold rush that occurred back in the late 1990s, when users scrambled to buy up valuable .com and .net domain names and then resell those names for a profit. Similarly, users are speculating on different .eth domain names in hopes of profiting from those ENS names. However, ENS domains are quite unlike Internet domain names in some interesting ways.

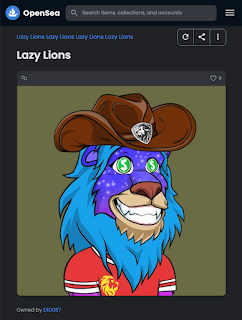

Internet domain names, such as cisco.com, are governed by a centralized non-profit organization named ICANN that has a Uniform Domain-Name Dispute-Resolution Policy in place to resolve "trademark-based domain-name disputes." However, no such framework exists in the ENS domain space. Once an ENS domain name has been registered it is placed on the blockchain, and cannot be taken away. ENS domains acknowledges this in their FAQ:

It may come as no surprise that ENS domains such as cisco.eth, wellsfargo.eth, foxnews.eth and so on are not actually owned by the respective companies who possess these trademarks. Rather, they're owned by third parties who registered these names early on with unknown intentions. The risk here is obvious: Nothing prevents the owner of the ENS domain wellsfargo.eth from using that name to trick unsuspecting users into believing that they are dealing with the real bank.

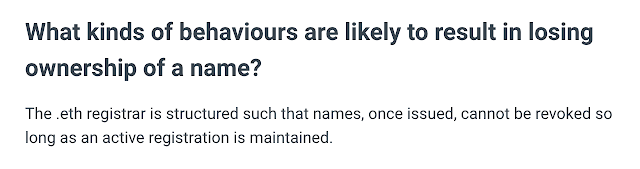

One of the other interesting phenomena surrounding ENS domains are the use of these names by individuals who trade cryptocurrency or buy NFTs to signal that they are part of the in-group. For example, searching on Twitter yields many users who proudly display their ENS domain name in either their Twitter name or bio. Because these ENS names point to wallet addresses, any person can inspect the contents of the wallet associated with the name at any time. Imagine walking around advertising how much money you had on you to anyone who wanted to know?

Depending on the ENS name chosen, this can also have the effect of de-anonymizing the wallet address owner. People are registering their names as ENS addresses, so it is fairly common to see ENS names like DebbieSmith.eth.

The use of ENS domain names also has the effect of advertising the cryptocurrency balance the owner carries in their wallet and their NFT holdings. A cybercriminal hoping to maximize their returns would naturally choose to target those users with the largest balances. The risk here is not limited to cyber crime. If the ENS domain holder is a known private individual, nothing would stop a criminal from buying a $5 wrench and conducting a physical attack (aka a rubber hose cryptanalysis attack) on that user, forcing them to give up the contents of their wallet. Physical attacks targeting cryptocurrency holders have already occurred.

Using a simple search in Twitter, Talos identified several hundred (~750) accounts advertising their .eth domain names in either their Twitter name or bio. We collected these ENS domain names into a list and then looked up the contents of the wallets to see how many "whales" could be easily identified and located. Almost 4 percent of the .eth addresses found by Talos contained more than $100,000 in Ethereum. Approximately 9 percent of the .eth addresses contained more than $30,000. For some of these users, their NFT collections are even more impressive.

Someone has even managed to create a database of nearly 50K Twitter users who display their ENS names called the Leaderboard. While the whole list doesn't appear available for download, spidering through the ~500 pages of .eth names would probably not be prohibitively difficult.

How hard is it to identify the person behind an ENS domain? Besides outright registering their full legal names, many ENS-domain-advertising Twitter users included their hometown in their public Twitter profile, and often included links to other social media accounts such as LinkedIn or Facebook. Sometimes, the tweets from the accounts revealed specific details about the user's physical location, such as events they were planning to attend. For many, identifying their real world identities and physical locations starting from the ENS domain and Twitter account was almost trivial.

Social engineering attacks dominate Web 3.0

When users are adapting to new technology for the first time, one of the biggest risks is the threat of social engineering. Unfamiliar technology can often lead users into making bad decisions. Web 3.0 is no exception. The vast majority of security incidents affecting Web 3.0 users stem from social engineering attacks.

Cloning wallets

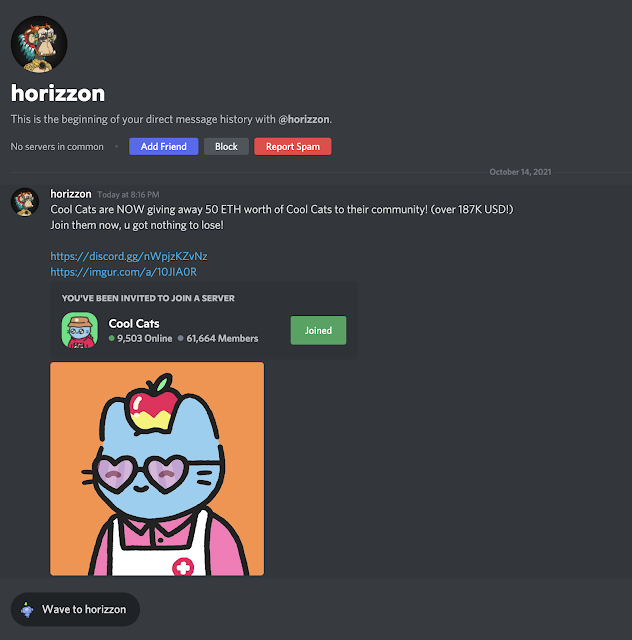

Many social engineering attacks can be avoided by following that old adage: if it sounds too good to be true it probably is. For example, below is a direct message I received letting me know that the Cool Cats NFT project is giving away 50 ETH worth of Cool Cats to their community. There is even a link to the (fake) Cool Cats Discord server.

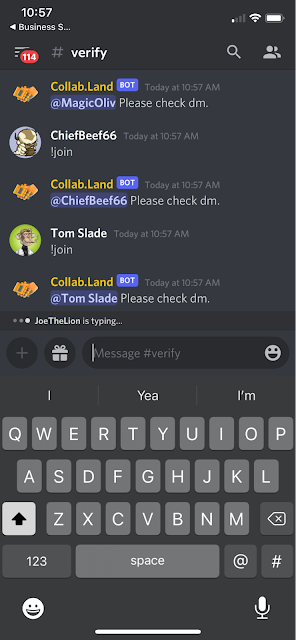

When you join the Discord community, you are presented with a #verify channel and what appears to be many users verifying their identity. Anything typed in besides the !join command will be erased from the chat log. (Mentioning the word "scam" will get you booted from the Discord altogether.)

If you type the !join command you will receive a direct message from the attackers. They will give you a URL to visit to verify your identity. The end goal is to trick the user into giving up their "seed phrase," and user's are losing significant amounts of money to scams such as this.

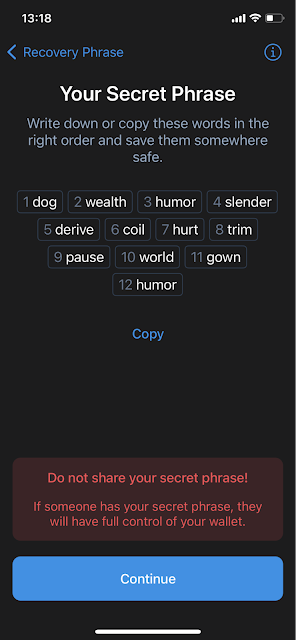

The security of a cryptocurrency wallet rests in public-private key cryptography. In the event that a cryptocurrency wallet is lost or destroyed, a user can recover their wallet, and all of its contents, using a 12- or 24-word "seed phrase" which is essentially, their private key. Anyone with knowledge of the seed phrase (private key) can clone a cryptocurrency wallet and use it as their own. Thus, many cybercriminals who are seeking to steal cryptocurrency or NFTs target a user's seed phrase.

NEVER, EVER TELL ANYONE YOUR SEED PHRASE!

"I'm from Metamask, and I'm here to help."

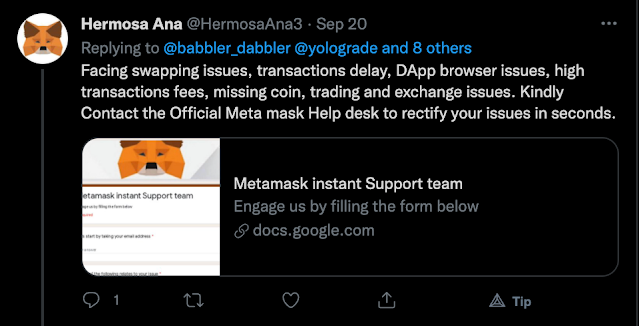

Another method attackers use to separate users from their seed phrase is to pose as a customer support agent offering help. If a user has a question or needs assistance, they may post on Twitter, or possibly in the "help" channel of a Discord server. Attackers monitor these channels, and will then contact the user offering helpful advice. In fact, if you tweet about having any kind of trouble and include the word "Metamask" in your tweet you will receive replies from scammy support bots.

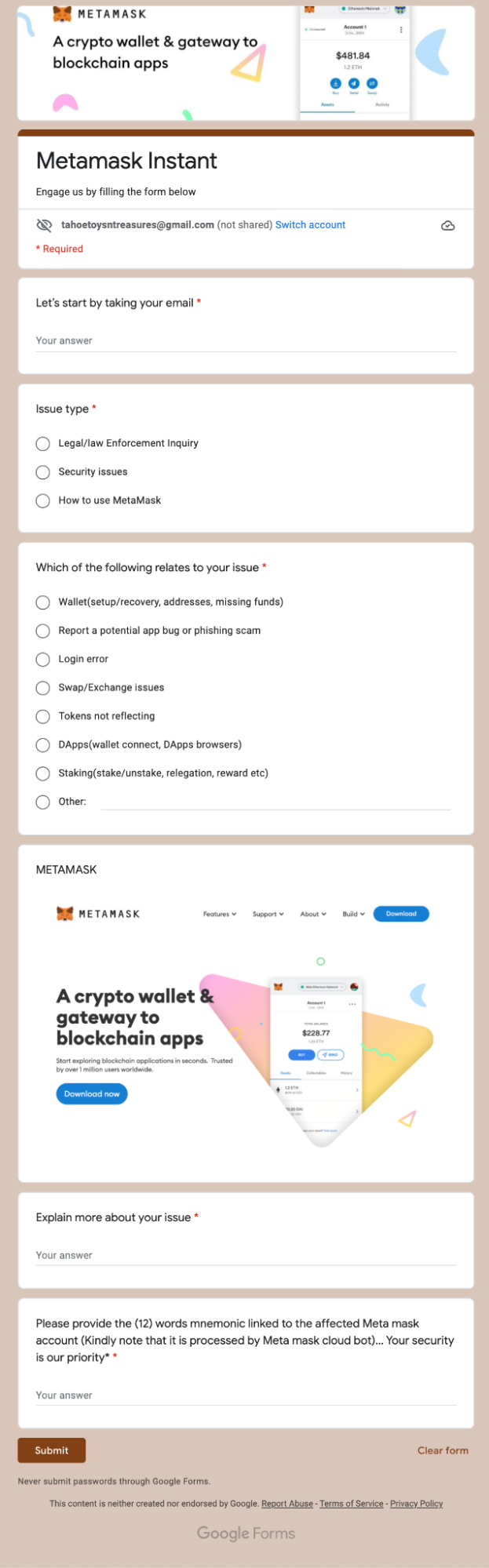

Of course, when the user follows this advice and navigates to the linked Metamask Support form, they are asked to provide their 12-word Metamask seed phrase:

How the tables have turned

Most users eventually learn that their seed phrase is never something to be shared with others, however, a few enterprising cybercriminals are doing just the opposite. Some Web 3.0 attackers are intentionally leaking their cryptocurrency wallet seed phrase to take advantage of unscrupulous users.

The idea is fairly simple: Attackers create a cryptocurrency wallet and load it with some cryptocurrency tokens, such as USDT (tether). The attackers then leak their 12-word cryptocurrency wallet seed phrase. Unethical third parties discover the leaked seed phrase, use it to clone the attacker's cryptocurrency wallet, and in the process discover that the wallet carries a balance of several hundred dollars worth of cryptocurrency tokens.

Ethereum-based cryptocurrency tokens such as USDT cannot be moved from one wallet address to another without paying a gas fee in Ethereum. A gas fee is paid to third parties to cover the costs of processing and validating the transaction on the Ethereum blockchain. To remove the USDT stored in the attacker's wallet, a user must first transfer a small amount of Ethereum into the wallet to cover these mandatory gas fees. The attackers, however, are vigilant and constantly monitoring the blockchain for activity involving their wallet address. The attackers instantly detect when someone transfers Ethereum into their wallet and before the USDT tokens can be transferred out, the attacker moves the small amount of Ethereum intended to pay for gas into a separate wallet. An example of such an attack can be seen here. Notice that a small amount of ETH comes into the address only to be transferred out to a separate wallet seconds later.

"Thar she blows!" — Scamming using whale wallets

In the world of cryptocurrency, there are high-profile accounts that hold a large amount of cryptocurrency or NFTs known as "whales." According to some estimates, only about 40,000 whales own about 80 percent of all NFT value. Clearly, much of the driving force behind the market for NFTs is driven by these whale accounts. There are smaller investors that monitor these whales' cryptocurrency wallets for activity and when a new NFT is purchased or minted, the investors mimic the whales' trades to make more money for themselves. Seems like a simple strategy for success — so what could possibly go wrong?

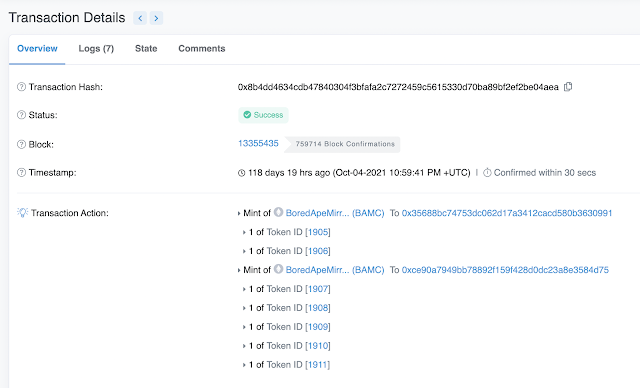

Clever scammers have caught on to the fact that there are many smaller investors watching these whales' wallets, and they use this fact to socially engineer these whale watchers into investing in their project. The scam is pretty simple: Create an NFT project such as Bored Ape Mirror Club, and attract some users to mint an NFT from your project. Every time someone mints a new NFT, the smart contract mints several additional NFTs from the project and deposits those NFTs into the accounts of the whales. Third parties who are watching the whales' wallets see the NFT minting activity and proceed to mint NFTs from the same project for themselves.

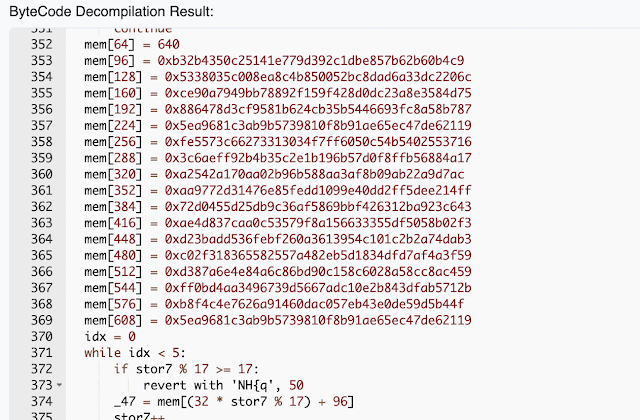

Looking up the smart contract address for the Bored Ape Mirror Club, we can see that the source code for this smart contract has not been published. Most legitimate NFT projects freely publish their source code for their smart contract. The fact that this project's code has not been published should be a red flag for potential investors. Luckily, there are tools that can be used to decompile the bytecode. From the recovered source code, we can see an array is set up with values pointing to whales' wallet addresses.

Looking at some of the minting transactions associated with this smart contract, we can see the contract first mints the NFTs that the buyer had purchased, but additionally, it also mints several more NFTs and deposits them into one of the whale wallets. In this example below, the buyer mints two NFTs, and after that the smart contract mints an additional five NFTs and deposits them into a wallet address, (0xce90a7949bb78892f159f428d0dc23a8e3584d75) belonging to "Cozomo de' Medici" (aka Snoop Dogg).

Malicious smart contracts

While some attackers focus on exploiting bugs in legitimate smart contracts, other attackers take a different approach and write their own malware which is placed onto the blockchain in the form of malicious smart contract code. Malicious smart contracts have all the standard smart contract functions and parameters that users expect, however they behave in unexpected ways.

Sleepminting: Faking NFT provenance

If you look at the ERC-721 NFT Specification you will notice that it contains prescriptions for function names and function parameters, but contains no information about the contents of the functions themselves. In fact, many NFTs actually use the same smart contract. The basic smart contract template is modified slightly to accommodate the needs of the specific NFT project. However, nothing prevents attackers from writing their own ERC-721 smart contract code – and many do.

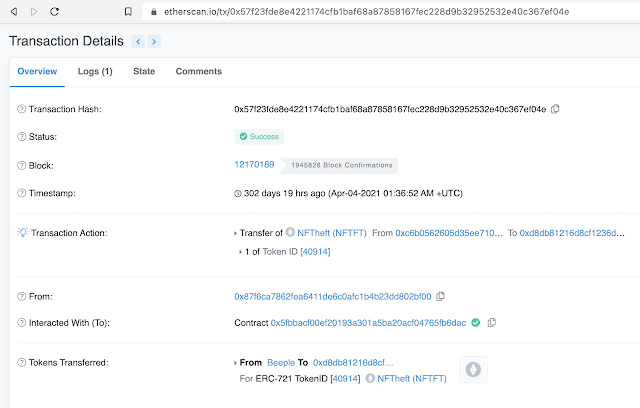

Back in April 2021, a hacker by the pseudonym of "Monsieur Personne" forged an NFT by artist Beeple using a malicious smart contract they designed. "Sleepminting" attacks, as they are called, involve creating an ERC-721 NFT smart contract that allows adversaries to mint NFTs to others' wallets, and transfer the minted NFTs from those other wallets so the NFT can be sold to an unsuspecting buyer. Below is a screenshot of a transaction which clearly shows an NFT token that was transferred out of the account belonging to "Beeple."

While the attacker cannot control the crypto address used to transmit the transaction to the Ethereum network (the "From" address above, 0x87f6ca7862fea6411de6c0afc1b4b23dd802bf00), they do control the contents of the data about the NFT minted via their own malicious smart contract. In this example, in the "Tokens Transferred" section, the attacker has set the "Tokens Transferred From" and "To" addresses themselves. This way, they can forge the provenance of an NFT on the Ethereum blockchain. An unsuspecting buyer might consult the blockchain to verify that this NFT really was minted by the artist Beeple, and according to the data on the blockchain, this would seem to be true.

Attackers trick users into giving access to wallets

Sometimes it is necessary to grant a third party permission to perform transactions involving tokens inside your cryptocurrency wallet. Applications such cryptocurrency swaps (ex., Uniswap) and NFT marketplaces (OpenSea, etc.) will ask their users for permission to access/modify the contents of the user's cryptocurrency wallet. Once the third-party access is approved, users of the application can swap tokens or list NFTs for sale without paying additional gas fees each time.

Attackers have figured out that if they can trick a victim into giving third-party approval over the contents of the victim's cryptocurrency wallet, that they can use that permission to drain the contents of the user's cryptocurrency wallet.

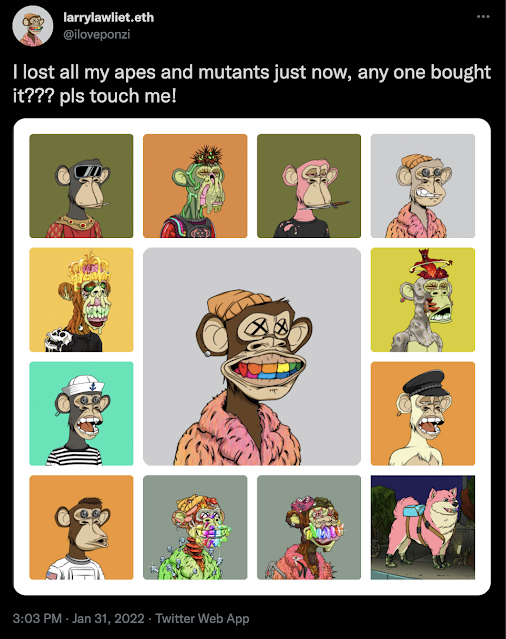

For example, on Jan. 31, 2022, a Twitter user by the handle @iloveponzi posted that they lost several very valuable NFTs.

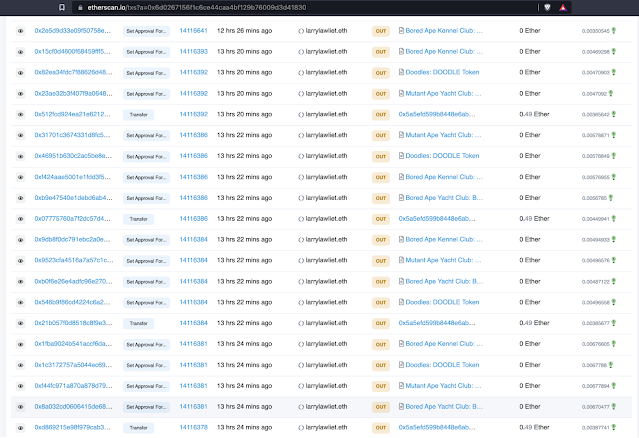

Looking up Larry's Twitter ENS domain name gives us a wallet address of "0x6d0267156f1c6ce44caa4bf129b76009d3d41830". When we review the transactions associated with this wallet address, we can see lots of "SetApprovalForAll" transactions and a few transfers.

If we take a deeper look at the transfers that occurred around the same time as the SetApproval transactions, we can see the likely explanation for how this person lost their NFTs. It turns out that the "Moshi Mochi" NFT Discord server was recently hacked and the attackers posted a link where 1000 additional Mochi NFTs could be minted. It appears Larry may have connected his wallet to the attackers' website and attempted to mint some more Mochi NFTs, but instead, by interacting with the malicious smart contract, he accidentally gave permission to the attackers to move his NFTs out of his wallet.

The ultimate lesson learned here is that losing your seed phrase isn't the only way that criminals might steal the contents of your crypto wallet. Always be careful when you are reviewing pending cryptocurrency transactions. Take extra care when approving transactions that involve granting third parties access to your wallet/tokens.

Tips for staying safe on Web 3.0

Although Web 3.0 technology hasn't yet evolved to deliver a fully-featured metaverse, there are many Web 3.0 technological advances already afoot. Here are some things to keep top-of-mind as you interact with this new technology.

- Practice good security fundamentals. Choose solid passwords, use multifactor authentication (MFA), such as Cisco Duo, wherever practical, use a password manager, segment your networks, log network activity and review those logs. Also be sure to examine internet, ENS domain and cryptocurrency wallet addresses for cleverly hidden typos, and never click on links that are presented to you unsolicited via social media or email.

- Protect your seed phrase. Never, EVER, give your seed phrase (sometimes it comes in the form of a QR code) to anyone. Increasingly, cryptocurrency wallets are being used for identification and personalization of metaverse content so if you lose your seed phrase you lose control over your identity and all your personal digital belongings.

- Think about using a hardware wallet. Any good defender will tell you that the most robust security systems utilize many different layers of security. Using a hardware wallet adds another layer of security to your cryptocurrency/NFT holdings since you must plug in the device, enter a pin, and approve/reject any transactions involving your wallet address.

- Research your purchases. Are you considering buying/minting NFTs? Look up the smart contract address and see if the source code is published. Unpublished source code is a red flag. Look up information regarding the developers of the project; anonymous developers can more easily pull the rug out from under you at any time. Make sure you are buying from the correct project on the correct blockchain. If you are connecting your cryptocurrency wallet to purchase or mint an NFT, consider using a freshly generated wallet address holding just enough funds to cover the cost of your purchase. This way, if anything bad happens, you won't lose the entire contents of your main cryptocurrency wallet.

For additional insights regarding Metaverse security, read our Cisco Newsroom Q&A with the blog author.