Executive summary

Cisco Talos recently became aware of a leaked playbook that has been attributed to the ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) group Conti. Talos has a team of dedicated, native-level speakers that translated these documents in their entirety into English. We also translated a Cobalt Strike manual that the authors referenced while creating their playbook.

These documents, written mostly in Cyrillic, were allegedly released by an affiliate upset with Conti. We believe that this translation is an extremely important contribution to the community, as machine-translated efforts have missed some interesting insights and led to some garbled passages.

Notably, the LockBit operator we interviewed warned us that something like this would take place. They stated that in a ransomware cartel, "Someone will sell them out from the inside," which is allegedly what took place in this case. The LockBit operator also told us that ransomware actors use various channels on the messaging app Telegram to stay on top of the latest exploits and attack trends. A look into a list of Telegram channels deemed interesting by the playbook authors shows numerous channels that were potentially leveraged for this exact use.

Talos' main takeaway from this playbook is that operators of all skill levels are involved with Conti. Some adversaries who are very new to the malware scene could follow this playbook to compromise a major, enterprise network with relatively little experience. At the end of this post, we've attached a full English translation of the documents.

Translation notes

While translating, our linguists discovered many grammatical mistakes, potentially indicating the writing process was rushed. But based on the language used, the authors likely possess at least a high school education. It is unclear whether the document was originally written entirely in Russian or they machine translated some English-language documents and included them in the playbook. The document contains some peculiar word choices that could be caused by auto-translation, or just poor writing. The playbook contains transliterated abbreviations, words and phrases, though this could be because there are no equivalents in Russian or the authors were unaware or preferred not to use them. However, even if it included machine translations, the playbook was likely later reviewed and edited to sound natural for a Russian-speaking audience. Regardless, it is clear that the authors pulled information from a variety of open-source materials in compiling the document. There are French passages present in various documents, as well, but only as examples of Cobalt Strike output, likely indicating that they were created during or copied from an attack targeting French companies.

Insights into the adversary

References to team leads, chats and conferences indicate that the group is at least somewhat well-organized. They also display a familiarity with corporate network environments, such as where prized assets are located and how to access them. This is particularly true for U.S. and European networks, which they note have enhanced documentation that provides for easier targeting. Of note, the only "geographical" mention by the adversaries was the mention of U.S./EU active directory (AD) structures. Their instructions, which are meticulous and easy to follow, also demonstrate that they are efficient and methodical.

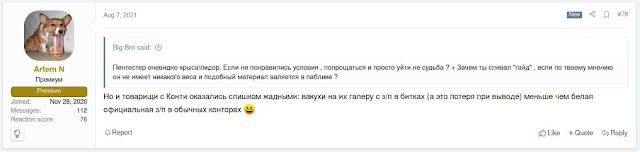

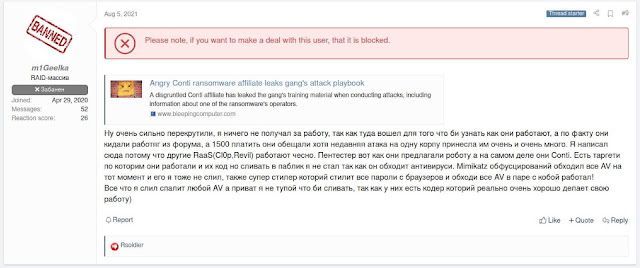

Through the leaker's posts, we learned that the alleged salary for a Conti pentester was around $1,500 USD. Several dark web posts noted that this was relatively low and others said it is more profitable to be legitimately employed than to work with Conti, based on their low payments as a whole.

|

| Actors discuss low payments for Conti. |

Insights into the leaker

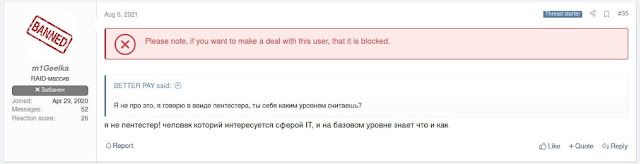

From information derived from the dark web, we learned the alleged identity of the leaker is "m1Geelka." This is apparently a young individual who was a lower-level member of Conti.

|

m1Geelka claims that they are not a pentester but are interested in IT. |

Based on information from their Telegram account, they appear to be based in Ukraine. M1Geelka claimed they were not paid by Conti for their services, prompting them to release this information to exact revenge on Conti.

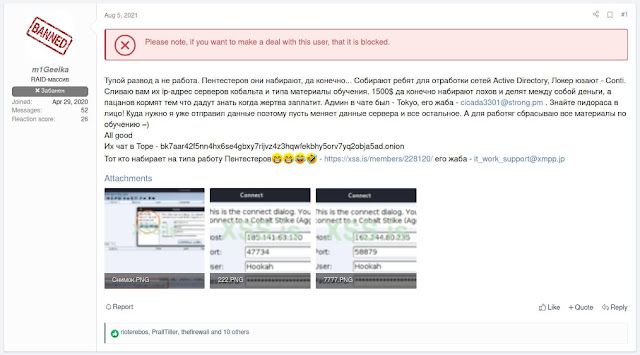

|

| Post containing the initial leaked documents. |

Later, they claimed they leaked the documents to better understand Conti and not for revenge, and they only leaked elements that could be detectable by anti-virus (AV) software, not more private elements, since the leaker respects the work of their coders.

|

| m1Geelka clarifies their reasons for leaking the documents. |

Barrier to entry

One of the biggest takeaways during the translation was the overall thoroughness and detail of these playbooks. The level of detail provided could allow even amateur adversaries to carry out destructive ransomware attacks, a much lower barrier to entry than other forms of attacks. This lower barrier to entry also may have led to the leak by a disgruntled member who was viewed as less technical (aka "a script kiddie") and less important.

Hunting for admin access

The adversaries list several ways to hunt for administrator access once on the victim network. They use commands such as Net to list users and tools like AdFind to enumerate users with access to Active Directory, and even OSINT, including the use of social media sites like LinkedIn to identify roles and users with privileged access. They note that this hunting process is particularly easy in U.S. and EU networks because of how they are structured and how roles and responsibilities are commonly detailed in comments.

Cobalt Strike

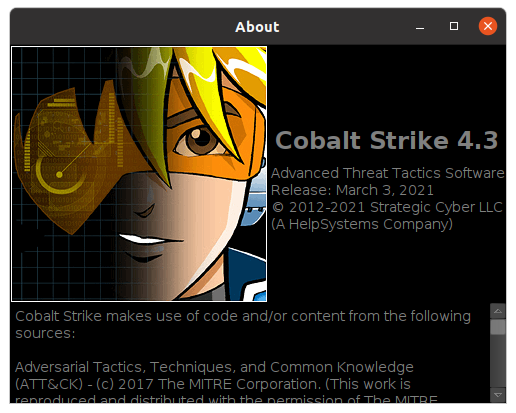

The primary tool described in this playbook is the red-teaming framework Cobalt Strike. The release included a version 4.3 of Cobalt Strike, and the JARM hash for the server matched what we would expect from a cracked Cobalt Strike server. The tool worked well. The playbook also pulled heavily from a Russian-language manual describing how to conduct attacks against Active Directory. We identified the Russian manual the authors were leveraging, and have translated and included it as well in this report.

|

| The Cobalt Strike version included in the playbook. |

Tools listed by the adversary

Besides Cobalt Strike, our linguists identified several other tools and native Windows utilities listed in the playbook. Of the tools and utilities mentioned, many have been commonly associated with previous ransomware operations, while others appear to be less familiar. Of the tools and command-line utilities the adversary mentioned, Talos identified those that have been commonly used by ransomware operators for reconnaissance and discovery, such as the use of ADFind to query for information on Active Directory (AD), and whoami to enumerate groups the user is a member of.

These actors also appear to be using two tools — Armitage and SharpView — that are not commonly seen in Cisco Talos Incident Response (CTIR) ransomware engagements. Armitage is a red-team toolkit built on the Metasploit framework that enables the user to launch exploits, scans, and more, while SharpView is a .NET port of PowerView, one of many tools contained within the PowerSploit offensive PowerShell toolkit.

SharpChrome and SeatBelt — two other tools we have not seen used in CTIR ransomware engagements — were also used for credential-dumping. SharpChrome is a Chrome-specific implementation of SharpDPAPI and attempts to decrypt logins and cookies. SeatBelt is a project written in C# that collects system data such as OS information (version, architecture), UAC system policies, user folders and more.

Comparisons to previous ransomware IR engagements involving Conti

Once our linguists translated the documents, we compared some of the techniques mentioned in the manuals and guides with activities and TTPs we have observed in CTIR engagements that involved the Conti ransomware. In many ransomware engagements, CTIR typically observes the adversary using PowerShell to disable Windows Defender real-time monitoring. This is in contrast to the adversary's instructions to manually disable real-time monitoring, which is much more interactive and time-consuming.

However, PowerShell wasn't the only tool mentioned by these adversaries to disable Windows Defender — the adversaries suggest using GMER as an alternative. GMER is a tool CTIR has observed across a few ransomware engagements, including at least one Conti engagement. GMER is marketed as an "anti-rootkit" tool and has been used by ransomware actors to identify protections and AV and to stop or remove them. Monitoring for the execution of GMER could help identify precursor activity to ransomware events. Since GMER hasn't been updated in several years, hash-based tracking is easy and effective.

CTIR assessed in at least one Conti engagement with a high degree of confidence that the adversary potentially had access to every account within the active directory (AD) environment. This is interesting given that the leaked Conti documents contain a number of techniques and advice on AD hunting in the victim environment. The accounts the adversary leveraged in at least one CTIR engagement also included Administrator and IT accounts, both of which were emphasized as valuable targets for AD hunting in the leaked playbook.

The adversaries also included instructions on CVE-2020-1472 Zerologon exploitation in Cobalt Strike. In a previous Ryuk ransomware engagement from Q2 2021, we observed the adversary access several additional resources within that environment and employ a privilege escalation exploit leveraging CVE-2020-1472 to impersonate a domain controller. Talos first started observing Ryuk adversaries using the Zerologon privilege-escalation vulnerability in September 2020 and continued updating their attacks on the health care and public health sectors in October. Some researchers have described Conti as the successor to Ryuk.

Conclusion Unfortunately, these ransomware cartels are not going anywhere, and in all likelihood, the problem will likely get worse before it gets better. These translated playbooks have given outsiders a glance into the techniques and behaviors of these groups once they are on a victim network, from the tools they leverage to their capabilities in using OSINT to find systems of interest on the network. One thing is certain: They clearly provide comprehensive documentation to their affiliates.

This documentation allows both seasoned criminals and those newer to the scene the ability to conduct large-scale, damaging campaigns. This shows that although some of the techniques used by these groups are sophisticated, the adversaries carrying out the actual attacks may not necessarily be advanced.

Additionally, this translation will provide defenders with a more complete view into the TTPs of these actors. This is an opportunity for defenders to make sure they have logic in place to detect these types of behaviors or compensating controls to help mitigate the risk. This translation should be viewed as an opportunity for defenders to get a better handle on how these groups operate and the tools they tend to leverage in these attacks.

Full translation

here in pdf.

the txt files via zip.