This blog post was authored by Jonas Zaddach and Mariano Graziano.

Executive Summary

Given the rapid pace of change in the threat landscape with new threats emerging and existing ones evolving, there are bound to be challenges defenders face. These challenges can manifest in multiple ways, such as processing and analyzing millions of new and unknown samples received each day. Other challenges include managing resource constraints for our tools used to automate malware analysis, developing antivirus signatures in an efficient manner that will identify malware families, and ensuring tools are able to scale as the number of samples needing to be analyzed increases. To help address these challenges, Talos is releasing a new open source framework called BASS.

BASS (pronounced "bæs") is a framework designed to automatically generate antivirus signatures from samples belonging to previously generated malware clusters. It is meant to reduce resource usage of ClamAV by producing more pattern-based signatures as opposed to hash-based signatures, and to alleviate the workload of analysts who write pattern-based signatures. The framework is easily scalable thanks to Docker.

Please note that this framework is still considered in the Alpha stage and as a result, it will have some rough edges. As this tool is open source and actively maintained by us, we gladly welcome any feedback from the community on improving the functionality of BASS. You can find source code for BASS here:

https://github.com/Cisco-Talos/bass

BASS was announced at REcon 2017 in Montreal, Canada.

Motivation

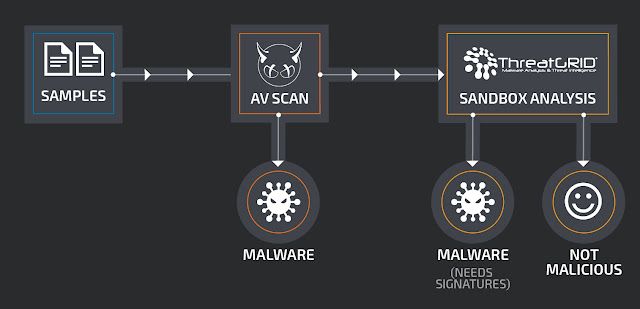

Talos receives about 1.5 million unique samples per day. While most of these samples are known threats that can be filtered out with a malware scan (with ClamAV) right away, a good portion of files remain where further analysis is necessary. At this point, we perform dynamic analysis on this subset where those files will be run in our sandbox, and then be classified as malicious or not malicious. The remaining portion of malicious files need to be processed further to generate ClamAV signatures which will filter this threat in the earlier stage malware scan in the future.

ClamAV's database increased by about 560,000 signatures in a three-month period (February to April) in 2017, which amounts to 9,500 signatures daily. A large part of these signatures are generated automatically as hash-based signatures. Compared to pattern-based or bytecode-based signatures (the other two main signature types which ClamAV supports), hash-based signatures have the disadvantage of only matching a single file per signature. Additionally, a high number of signatures translates to an increased footprint of ClamAV's signature database in memory. For this reason, we would prefer to have have more pattern-based signatures, which are comparably faster and easier to maintain than bytecode signatures, but are able to identify a whole cluster of files instead of just a single file.

BASS

BASS is meant to fill this gap. This framework is designed to generate ClamAV pattern signatures from chunks of binary executable code.

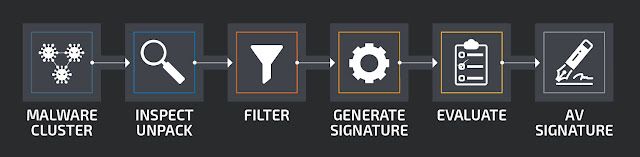

The framework ingests malware clusters. To keep the framework as simple and as flexible as possible, malware clustering is not part of BASS. The input interface is intentionally kept generic to be easily adaptable to new clustering sources. We currently use several cluster sources. A non-exhaustive list of our current sources is: Indicator of Compromise (IoC) clusters from our sandbox, structural hashing in case where we have a known malicious executable and find additional samples through structural similarity, and malware gathered from spam campaigns.

In a first step, the malware files are unpacked with ClamAV's unpackers. ClamAV can unpack and extract a wide range of archive formats, but also packed executables (like UPX) and nested documents (such as an EXE file inside a Word document). The resulting artifacts are inspected to gather information. Currently we use the file size and the magic string from the Unix file tool in the filtering step.

Next, the malware cluster is filtered. If files do not correspond to BASS' expected input (currently PE executables, though adding support for ELF and MACH-O binaries is trivial), they are removed from the cluster, or the cluster is outright rejected if not enough files remain.

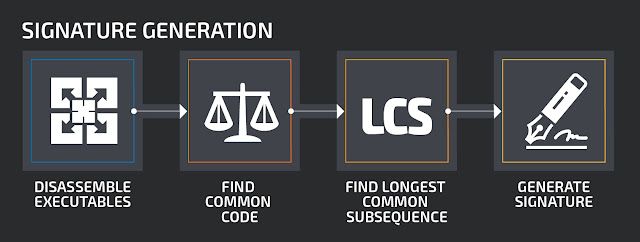

The filtered cluster then passes to the signature generation step. Here, the binaries are first disassembled. Currently we use IDA Pro as a disassembler, but other disassemblers like radare2 are able to produce the same information and could easily be swapped in as a replacement to IDA.

After disassembly, we need to find common code between the samples which can be used to generate signatures from. This step is necessary for two reasons.The first is because the signature generation algorithm is computationally very expensive and works well on short chunks. The second is because having a signature on code which is not only syntactically but also semantically similar is preferable. We use BinDiff as a code comparison tool. Again, the tool should be easily exchangeable, and we might integrate other comparison tools in the future.

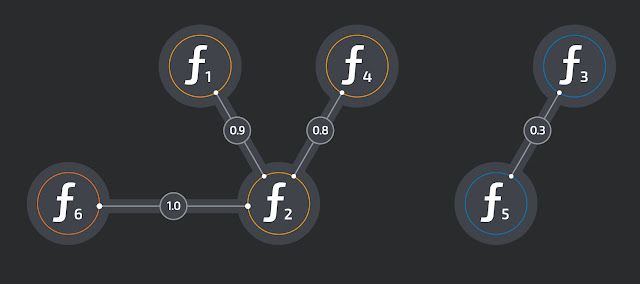

BinDiff compares each executable with every other in small clusters. In bigger clusters, comparisons are limited, as the number would explode. A graph is built from the function similarities where functions are the nodes and the similarity the edges. Finding a good common function amounts to finding a connected subgraph with high overall similarity.

In the above example, the subgraph of ƒ1, ƒ2, ƒ4, ƒ6 is a good candidate for a common function, as the overall similarity is high.

When a set of candidate functions in the binaries have been identified, the functions are checked against a function whitelist. This step helps to avoid generating signatures on benign library functions which have been statically linked into a sample. These functions are submitted to the Kam1n0 instance, whose database we previously pre-populated with functions of known clean samples. If a clone of a function is found, the subgraph selection from above is repeated for the next-best subgraph. Otherwise, the function set is retained for the next step: signature generation.

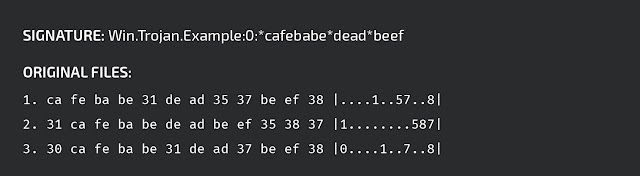

At this point, the actual signature generation can start. As ClamAV's pattern signatures are made to recognize subsequences in binary data, we apply an algorithm to all extracted functions to find the Longest Common Subsequence (LCS) between them (See the Appendix for the differences between a Longest Common Substring and a Longest Common Subsequence).

As the algorithm is already computationally expensive for two samples and even more so for several samples, we implemented a heuristic version described by C. Blichmann. An example output could look like that:

Finally, the signature needs to be tested before it is published. We automatically validate the signature against our false positive test set. For further scrutiny, we use Sigalyzer, a new functionality of our CASC IDA Pro ClamAV signature generation and analysis plugin (which will be updated later). Sigalyzer highlights the matched parts of a binary given a ClamAV signature triggering on that binary, and quickly gives the analyst a visual impression of the signature.

Architecture

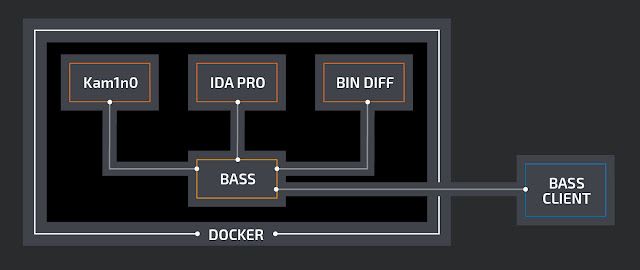

BASS is implemented as a cluster of docker containers. The framework is written in python, and interacts with the tools it uses through web services. The architecture is inspired from VxClass, which also used IDA Pro and BinDiff to generate ClamAV signatures, but was discontinued and, contrary to BASS, is not publicly available.

Limitations

BASS will only work on binary executables because the signature is generated from the code section of the sample. Additionally, BASS will only analyze x86 and x86_64 binaries. Support for other architectures may be added in the future.

We have observed that the framework does not work well on file infectors, which usually insert small and highly varying snippets of code in a host binary, and backdoors, which contain large amounts of (sometimes stolen) non-malicious binary code together with some malicious functions. We are working on improving the clustering step to deal with these issues.

Finally, be aware that BASS is currently in Alpha stage and has some rough edges. Still, we hope to contribute to the community by open sourcing the framework and would gladly welcome any feedback and improvement suggestions.

Appendix

Longest Common Substring versus Longest Common Subsequence

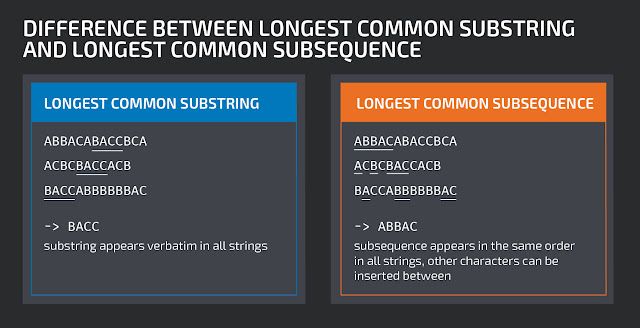

The following graphic illustrates the difference between a Longest Common Substring and a Longest Common Subsequence. In this blog post, we refer to the Longest Common Subsequence as LCS.