This post was authored by Dave Liebenberg

In the past few months, Talos has observed an uptick in the number of Chinese websites offering online DDoS services. Many of these websites have a nearly identical layout and design, offering a simple interface in which the user selects a target’s host, port, attack method, and duration of attack. In addition, the majority of these sites have been registered within the past six months. However, the websites operate under different group names and have different registrants. In addition, Talos has observed administrators of these websites launching attacks on one another. Talos sought to research the actors responsible for creating these platforms and analyze why they have become more prevalent lately.

In this blog post, we will begin by looking at the DDoS industry in China and charting the shift toward online DDoS platforms. Then we will examine the types of DDoS platforms created recently, noting their similarities and differences. Finally, we will look into the source code likely responsible for the recent increase in these nearly identical DDoS websites.

DDoS-as-a-Service in China

DDoS tools and services remain some of the most popular offerings in the Chinese underground market. A look at one of the most popular Chinese marketplaces, DuTe (独特), reveals a variety of DDoS-related tools, including actual attack tools as well as associated tools such as brute forcers for different vectors including SSH and RDP.

In addition, Chinese social media applications such as WeChat and QQ have hundreds of group chats devoted to DDoS groups, tools, malware, and the exchange of targets. The people interacting in these channels include members of hacking groups, customers, as well as agents and advertisers who can act as intermediaries.

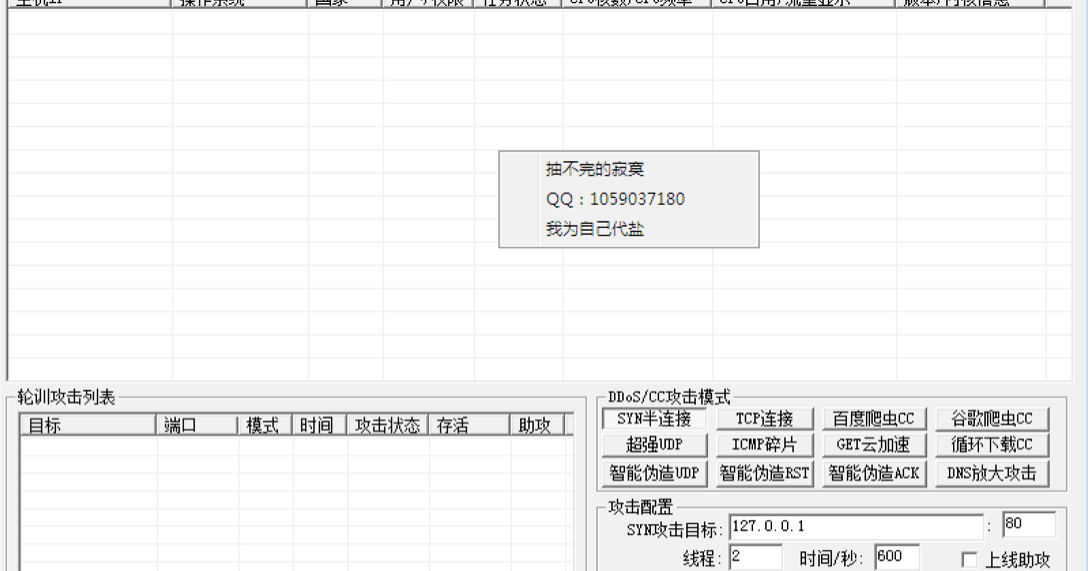

Previously, the predominant offering in these group chats were tools that users could purchase, download, and then operate from their own machine. A good example of this type of tool was the TianFa Pressure Testing System.

|

| TianFa DDoS tool |

These kinds of tools manage and provide information about a user’s botnet, and then allow the user to customize an attack event, selecting a target and choosing an attack method. Users can purchase the tool, download a copy, and use it with their own servers and botnets. Occasionally, hacker groups also bundle servers or a certain amount of bots with purchases, or include brute-forcing tools to help users grow their own botnet, but the end-user would be in charge of maintaining and deploying the tool.

The Rise of Online DDoS Platforms

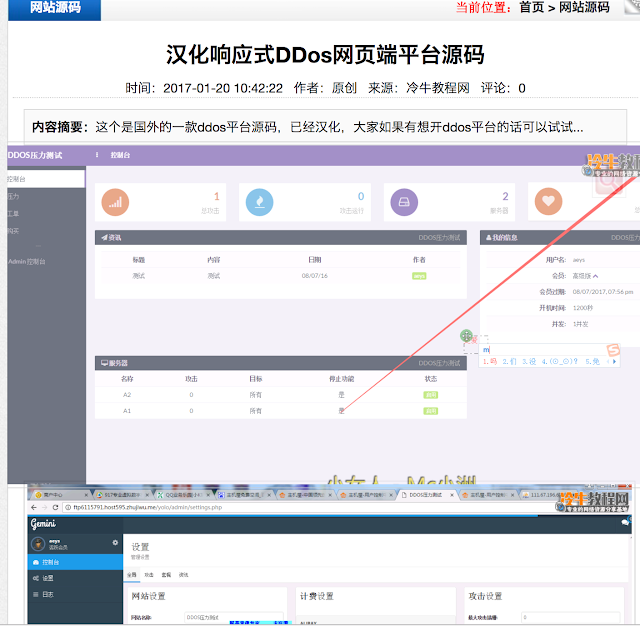

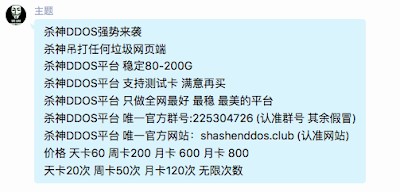

Recently, Talos has noticed a gradual paradigm shift underway in the group chats. Advertisements for online DDoS platforms have begun to appear more frequently.

|

| Advertiser promotes “ShaShen” Online DDoS Website |

After inspecting several of these websites, Talos noticed that many had identical login and registration pages, down to the same background image:

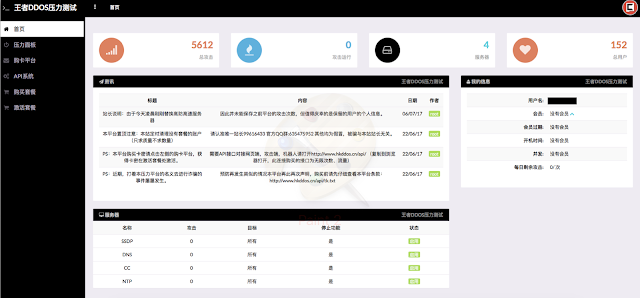

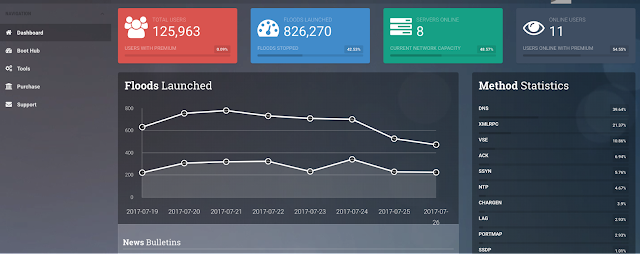

In addition, Talos observed that many of these websites have a nearly identical website design and layout, displaying the number of active users and servers online as well as the total number of attacks that have been carried out (although these numbers vary between groups). In addition, the sites contain announcements from group administrators on recent updates to the tool, its capabilities, or restrictions on its use. In the sidebar, users can register an account, purchase an activation code to begin launching an attack, and then attack a target, either through the graphical interface set up on the website or through identical command line calls with look like this:

http://website_name/api.php?username=&password=&host=&port=&time=&method=

|

| Nearly identical website layout for ShaShen DDoS group and Wang Zhe sec DDoS group. |

Besides the uncanny similarities in design and function, the majority of the websites had the word “ddos” in their domain names, i.e. “shashenddos.club” or “87ddos.cc.” Since these sites were all recently registered, beside relying on intelligence from Chinese social media, Talos was able to identify several new websites by using Cisco Umbrella’s investigate tool to conduct a regex search for recently-registered domains with the word “ddos” in them. Using these combined search methods, Talos was able to identify 32 nearly-identical Chinese online DDoS websites (presumably there are more out there, since not all of these websites had “ddos” in the their domain name).

Because of the similarities in the pages, and the fact that some individuals registered multiple sites for the same group, we initially suspected that one actor was potentially responsible for all the sites and was merely operating under different aliases. In order to test our theory we registered an account with each site and also used Cisco Umbrella’s investigate tool to examine each site’s registration info.

We soon revised our one-actor theory. After registering accounts at various sites we noticed that many employed different third-party Chinese payment websites where users could purchase activation codes (typical prices range from around 20RMB for a day-use code to around 400RMB for a month-use pass). In addition, the announcements on the pages displayed different tool capabilities (some advertised attack power of 30-80gbps, while others went as high as 300gbps), as well as different contact information, including various QQ accounts for customer service as well as group chat numbers for customers and administrators to interact. There were also vast differences in the numbers of attacks and users, with one page (www[.]dk[.]ps88[.]org) listing 168,423 attacks made by 44,238 users and another (www[.]pc4[.]tw) listing 24 attacks made by 13 users.

In addition, the websites’ registration information also revealed key differences. Most of the websites had different registrant names and emails, as well as different registrar’s listed. However, there were some similarities as well: almost all had used Chinese registrars, the majority were registered in the past 3 months, and nearly all were registered in the past year. In addition, over half were hosted on Cloudflare IPs.

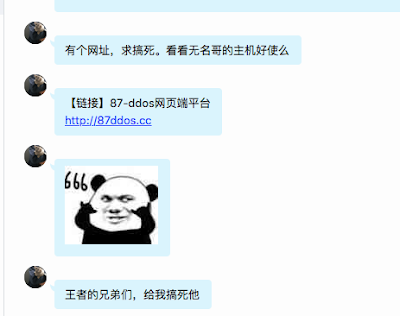

Our final confirmation that different actors were behind these websites came when Talos was monitoring a QQ group chat channel affiliated with one of these online DDoS platforms called Wang Zhe sec. We observed a group member requesting an attack on a rival online DDoS group, 87 DDoS, with which we had also already registered an account.

|

| A member of Wang Zhe sec chat group requests attack on rival online DDoS website |

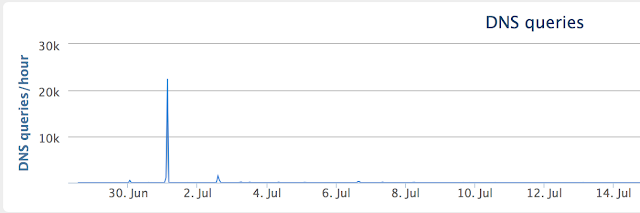

Talos joined a number of group chats associated with online DDoS platforms and observed multiple actors discussing launching DDoS attacks on rival groups. Indeed, a look at some of the traffic of these online DDoS websites indicates that they had possibly experienced DDoS attacks.

|

| Traffic for the website of 87 DDoS reveals dramatic spike around July 1, 2017 |

A Glimpse Behind the Curtain

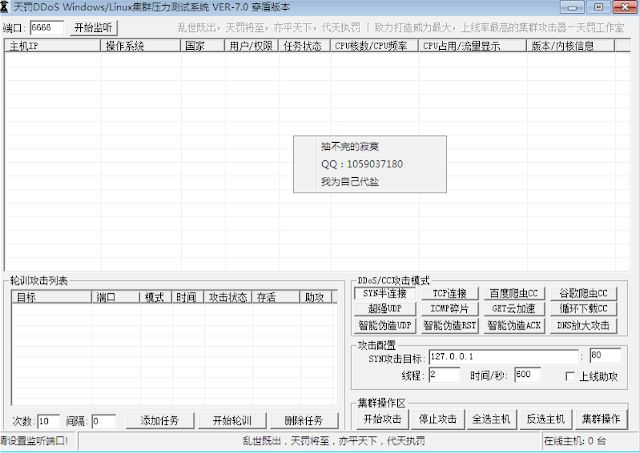

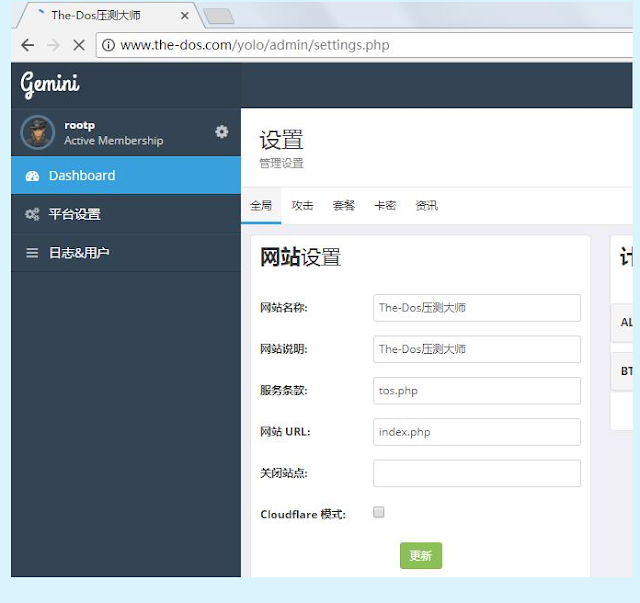

We had strong indications that multiple groups were building nearly identical online DDoS platforms, but still had no idea why they were using the same layout or why they had all begun to appear so recently. We began to gain insight into the story behind these questions after an actor in a group chat run by a Chinese hacker group posted a screenshot of the admin page for his online DDoS platform:

|

| An actor posts a screenshot of their admin panel for their online DDoS platform |

The screenshot showed a setup page where the actor could choose a name for the site, write a description, and provide links to the terms of service and URLs. Several items of interest jumped out at us, providing further avenues for research. First we noticed the word “Gemini” in the top right corner. Second, we noticed the unique URL of “/yolo/admin/settings.” Finally, we noticed a button at the bottom of the screen where an administrator could select “Cloudflare mode”, which reminded us how many of the websites had been hosted on Cloudflare IPs

Finding and Analyzing the Source Code

We now had a hunch that the rise of these nearly identical websites was due to some sort of shared source code, which was likely being offered on Chinese underground hacking forums and marketplaces. We went to several of the forums and searched for the “/yolo/admin/settings” URL present in the screenshot. We discovered that several forums had posts offering the sale of source code for an online DDoS platform, all identifying it as a foreign DDoS platform that had been translated into Chinese.

Many of the postings were made in early 2017 or late 2016, corresponding to the timeline of the rise in the DDoS platforms. And the pictures in the advertisements looked identical to websites we had been seeing:

Talos was able to obtain a copy of the source code and went about analyzing it. It was clear that the source code corresponded to the DDoS websites we observed. The PHP files contained icons that matched those found on the websites. In addition, the background that the majority of these sites employ was also found in the images folder:

The source code revealed that the platform relied on Bootstrap front-end design and ajax to load content. In the CSS files we found an author named as Pixelcave. Researching Pixelcave, we discovered that they offered Bootstrap-based website designs that looked similar to the online Chinese DDoS websites we had examined. We also noticed that Pixelcave’s logo was present in the top right hand corner of many of the DDoS websites we had found and was also included as an icon in the source code.

|

| Logo for Pixelcave, which was present on all the DDoS websites we identified. |

According to the source code, the platform has functions which pull information from mysql databases and assess a user’s standing (i.e. the amount of attacks, duration of attacks, and number of concurrent attacks a user is allowed based on payments they have made). It then allows a user to input a host, select an attack method, (i.e. NTP, L7) and duration. Provided that the method is supported by the actors and the target is not blocklisted, it calls servers to begin carrying out the attacks.

Interestingly, the source code provides a blocklist for sites that cannot be attacked, and includes “.gov” and “.edu” sites among them, although these can obviously be modified. In addition, it comes with a preloaded Terms of Service (in Mandarin) which absolves the administrators of the site from any responsibility for “illegal” acts and asserts that its services are only meant for testing purposes.

The code also allows administrators to monitor payments made, outstanding tickets, as well as an overview of the total amount of logins and attacks being contracted, and details about the attacks such as the host, duration of the attack, and which server is conducting the attack. The administrator can also set up an activation code system.

It is clear that the source code was originally written in English, but was modified so that the final platform would display Chinese language graphics (as advertised). The source code also provides options for administrators to set up payment systems through Paypal and Bitcoin. It is likely that Chinese actors would modify this by switching it to a Chinese payment system, like third-party payment sites or Chinese services like Alipay. In fact the icon for Paypal in one image folder is altered to resemble the Alipay icon.

It is unclear as of the time of this writing where the original source code derived from. However, there are several English language websites that offer online DDoS services, such as the tool DataBooter. These websites have some similarities to the Chinese DDoS platforms. For instance, they have a bootstrap-based design, are hosted on Cloudflare, and have similar graphics conveying the number of attacks, users, and servers online.

|

| Layout for databooter[.]com. The layout is somewhat similar to the Chinese online DDoS websites. |

Talos has observed actors selling source code for these types of English-language DDoS platforms on hacker forums in the past few years. It is possible that Chinese actors obtained this source code, or code based on it, and modified it to localize it more to Chinese consumers, though we have not found direct evidence of this.

Conclusion

The recent uptick in Chinese online DDoS platforms seems to be connected to source code for sale on Chinese hacker forums. This source code appears to be a localized version of code originally written for English language online booters.

Online DDoS platforms remain popular because of their easy-to-use interfaces and the fact that they already provide all necessary infrastructure to the user, so there is no need to build a botnet or purchase additional services. Instead, the user purchases an activation code through a trusted payment site and then simply enters in their target. This serves the function of enabling even the most novice of actors the capability to launch powerful attacks, depending on the strength of the DDoS group’s backend infrastructure.

Talos will continue to monitor Chinese hacker forums and group chats for newly-created online Chinese DDoS platforms as well as greater trends emerging in the Chinese DDoS industry.

IOCs:

Online DDoS Websites

www[.]794ddos[.]cn

www[.]dk.ps88[.]org

www[.]tmddos[.]top

www[.]wm-ddos[.]win

www[.]tc4[.]pw

www[.]hkddos[.]cn

www[.]ppddos[.]club

www[.]lnddos[.]cn

www[.]711ddos[.]cn

www[.]830ddos[.]top

www[.]bbddos[.]com

www[.]941ddos[.]club

www[.]123ddos[.]net

www[.]the-dos[.]com

www[.]etddos[.]cn

www[.]jtddos[.]me

www[.]ccddos[.]ml

www[.]87ddos[.]cc

www[.]ddos[.]cx

www[.]hackdd[.]cn

www[.]shashenddos[.]club

www[.]minddos[.]club

www[.]caihongtangddos[.]cn

www[.]zfxcb[.]top

www[.]91moyu[.]top

www[.]xcbzy[.]club

www[.]this-ddos[.]cn

www[.]aaajb[.]top

www[.]ddos[.]qv5[.]pw

www[.]tdddos[.]com

www[.]ddos[.]blue

IPs

104[.]18.54.93

104[.]18.40.150

115[.]159.30.202

104[.]27.161.160

104[.]27.174.49

104[.]27.128.111

144[.]217.162.94

104[.]27.130.205

103[.]255.237.138

45[.]76.202.77

104[.]27.177.67

104[.]31.86.177

103[.]42.212.68

142[.]4.210.15

104[.]18.33.110

104[.]27.154.16

104[.]27.137.58

23[.]230.235.62

104[.]18.42.18

162[.]251.93.27

104[.]18.62.202

104[.]24.117.44

104[.]28.4.180

104[.]31.76.30