Performing analysis on a Visual Basic (VB) script, or when Visual Basic is paired with the .NET Framework, becomes an exercise of source code analysis. Unfortunately when Visual Basic is compiled to a Windows Portable Executable (PE) file it can become a nightmare for many malware analysts and reverse engineers.

Why is it used by malware? Visual Basic binaries have a reputation for making an analysts job difficult due to the many aspects of its compilation that differ from standard C/C++ binaries. To analyze a VB PE binary it helps to be familiar with the VB scripting syntax and semantics since their constructs will appear throughout the binary's disassembly. VB binaries have their own API interpreted by Microsoft's VB virtual machine (VB 6.0 uses msvbvm60.dll). Many of the APIs are wrappers for more commonly used Win32 APIs leveraged from other system DLLs.

Reverse engineering VB binaries will often involve reverse engineering VB internals for various VB APIs, a task dreaded by many. The entry point of a VB program diverts from the typical C/C++ or even Borland Delphi binary. There is no mainCRTStartup or WinMainCRTStartup function that initializes the C runtime and calls the developer defined main or WinMain function. Instead the Entry Point (EP) looks like this:

004014A4 start:

004014A4 push offset dword_40159C

004014A9 call ThunRTMain

004014A9 ; -----------------------------------------------------------------

004014AE dw 0

004014B0 dd 0

004014B4 dd 30h, 40h, 0

004014C0 dd 0E8235672h, 403451C6h, 0AAF1D6B9h, 88BB31A6h, 0

...

The call to ThunRTMain is just wrapper to call VB API (msvbvm60!ThunRTMain). The only argument to ThunRTMain is the address of an object. This structure is documented in several places online and Reginald Wong developed an IDA Pro IDC script (https://www.hex-rays.com/products/ida/support/freefiles/vb.idc) to parse the structure and label its members within the IDB. This will aid in understanding the objects used within the binary and their corresponding methods.

At this point it becomes an exercise of understanding the VB program based on the VB APIs used (there are some caveats, e.g. calls to Zombie_AddRef). Generally, VB programmers will have access to all the functionality they need through msvbvm60.dll, however, it is is possible to dynamically load API not available within the VB API through the DllFunctionCall function. The name implies the function will call the supplied function within a DLL, but this is not true.

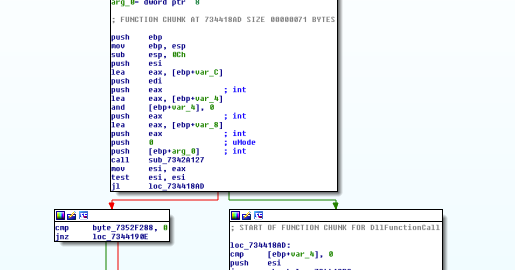

How does it work? DllFunctionCall takes in a structure that defines the wanted library and exported function, loads the library specified into memory, locates the address of the function provided, and returns the address. To know this we have to dive into the VB engine. Opening msvbvm60.dll in IDA Pro and navigating to the disassembly for DllFunctionCall we are met with a fairly small function (See figure DllFunctionCall graph). Within the first code block we see a call to sub_7342A127 with arg_0 as its first argument. At this point, all we know is DllFunctionCall has one argument that should provide (at a minimum) the library and export name. Based on what we currently know we can define our structure:

typedef struct _DllFunctionCallStruct {

void * lpLibraryOrExportName;

void * lpExportOrLibraryName;

} DllFunctionCallStruct;

|

| msvbvm60!DllFunctionCall |

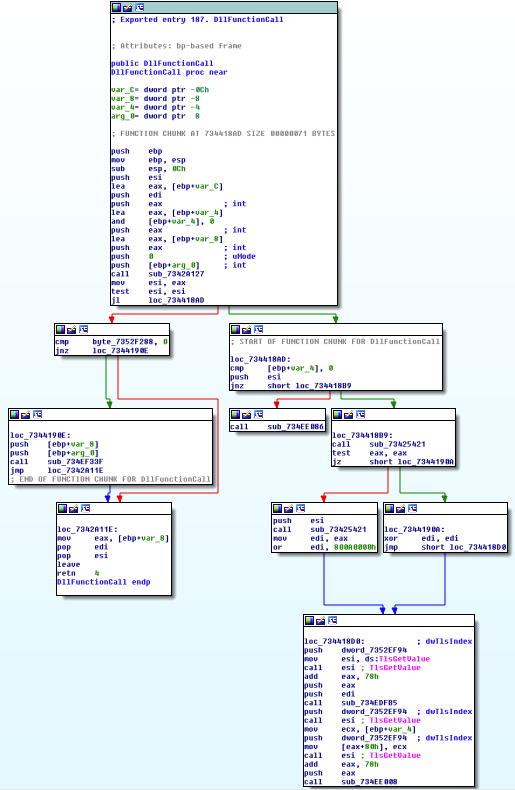

Going to the Structures window I created the structure, changed DllFunctionCall and sub_7342A127 function headers to reflect that arg_0 is typed as a DllFunctionCallStruct * and rename arg_0 in both functions to "struct". By examining sub_7342A127 we see this is where all the work happens (See sub_7342A127 function graph).

|

msvbvm60!sub_7342A127

|

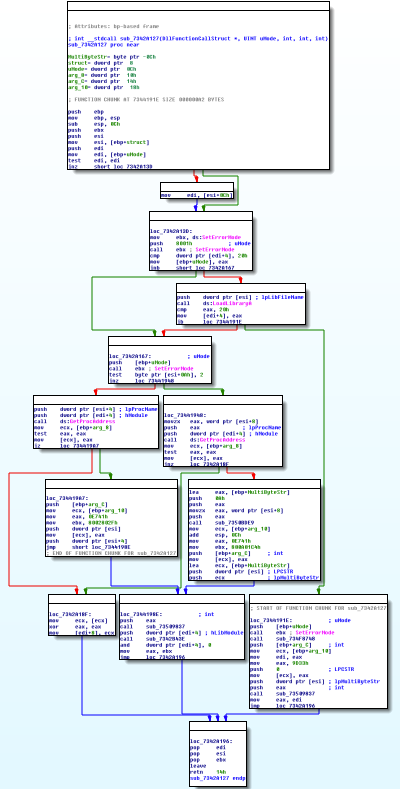

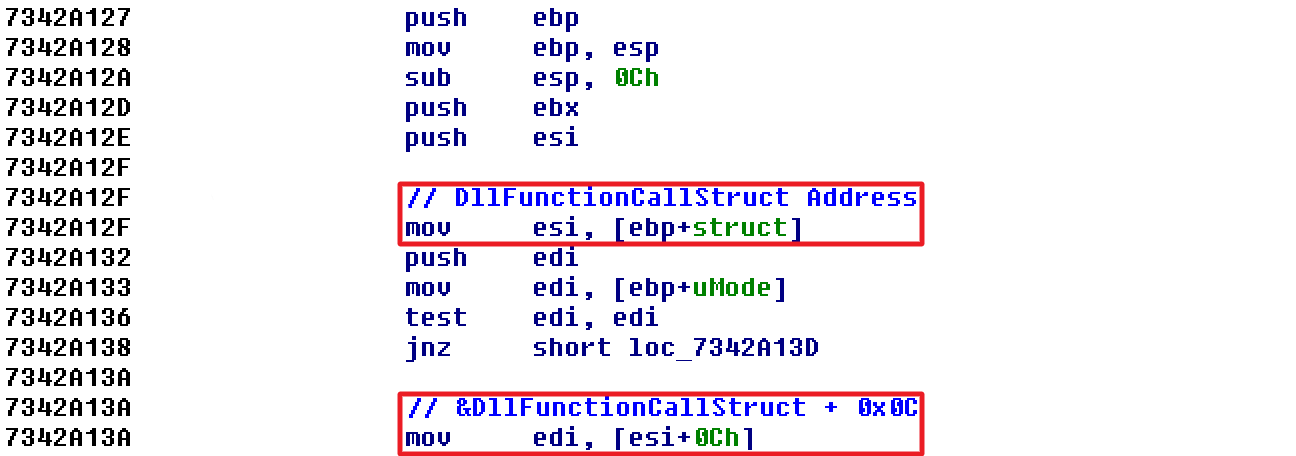

Analyzing the disassembly within sub_7342A127 we see our DllFunctionCallStruct structure assigned to ESI (first red box in figure sub_7342A127 part 1 below) and our assumptions of its composition is incorrect. The second red box highlights a new, unknown, member within our DllFunctionCallStruct structure. A new structure member is accessed at offset 0x0C (12) and saved into EDI (or &DllFunctionCallStruct + 0x0C).

|

msvbvm60!sub_7342A127 part 1

|

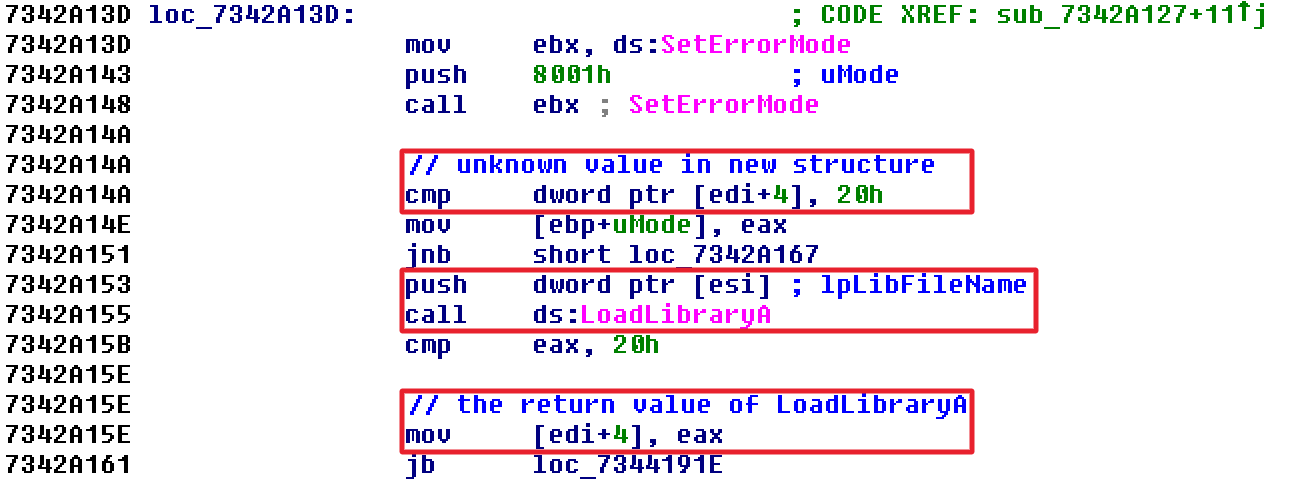

The new member is accessed at 0x7342A14A (first red box in figure sub_7342A127 part 2 below), however, it is accessed via an offset and a dereference. This tells us the new member at offset 0x0C is a pointer to a value, most likely a structure, with its own members (e.g. a member at offset 4). The call to LoadLibraryA (second red box in figure sub_7342A127 part 2 below) helps to fill in some of the assumptions we have made so far concerning DllFunctionCallStruct.

|

msvbvm60!sub_7342A127 part 2

|

The first member of DllFunctionCallStruct (&DllFunctionCallStruct + 0) must be a pointer to a character array containing the library name to be loaded (e.g. "kernel32.dll), thus the second member is a pointer to the string representing the exported function (e.g. “CreateFileA”). Finally, EDI is used to save the return value of LoadLibraryA (third red box in figure sub_7342A127 part 2 above), corroborating our suspicion that EDI is a structure. Below we create a new structure DynamicaHandles and rewrite DllFunctionCallStruct:

typedef struct _DynamicHandles {

0x00

0x04 HANDLE hModule;

0x08

} DynamicHandles;

typedef struct _DllFunctionCallStruct {

0x00 LPCSTR lpDllName;

0x04 LPTSTR lpExportName;

0x0C DynamicHandles sHandleData_unk;

0x10

} DllFunctionCallStruct;

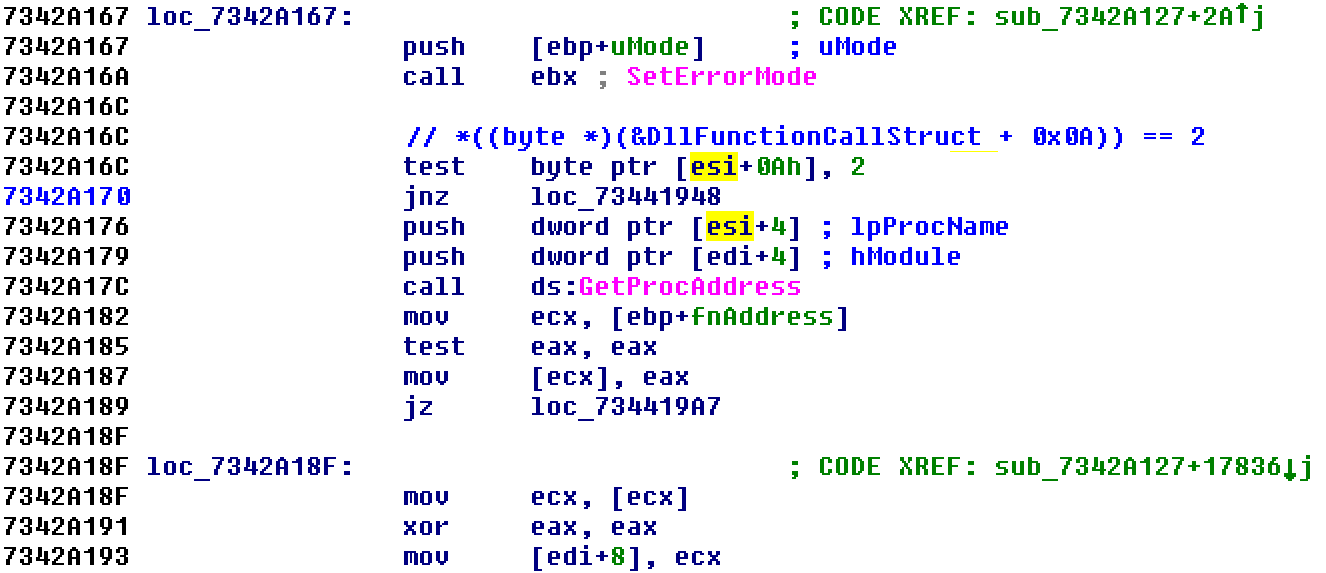

Continuing our analysis we confirm DllFunctionCallStruct + 4 is a pointer to the exported function name. However, we also see that DllFunctionCallStruct contains a byte at offset 0x0A (10) that is used for the comparison at 7342A16C. Examining both possible branches it becomes clear that this byte is significant for the function to determine if GetProcAddress is being called with the exported function's string representation or the export function's ordinal. After GetProcAddress is called arg_8 is used to save the value (arg_8 will be renamed to fnAddress) and its value is saved into the DynamicHandles structure at offset 8.

|

msvbvm60!sub_7342A127 part 3

|

Piecing this together DllFunctionCall argument is the structure defined below:

typedef struct _DynamicHandles {

0x00 DWORD dwUnknown;

0x04 HANDLE hModule;

0x08 VOID * fnAddress

0x0C

} DynamicHandles;

typedef struct _DllFunctionCallStruct {

0x00 LPCSTR lpDllName;

0x04 LPTSTR lpExportName;

0x08

0x09

// 4 bytes means it is a LPTSTR *

// 2 bytes means it is a WORD (the export's Ordinal)

0x0A char sizeOfExportName;

0x0B

0x0C DynamicHandles sHandleData;

0x10

} DllFunctionCallStruct;

Putting it all Together Great, we understand enough of the structure passed into DllFunctionCall, but how does this benefit us? It will aid us in locating dynamically loaded API functions in a VB binary. Most VB binaries making use of DllFunctionCall will have wrapper functions that follow this format:

mov eax, dword_ZZZZZZZZ

or eax, eax

jz short loc_XXXXXXXX

jmp eax

loc_XXXXXX:

push YYYYYYYYh

mov eax, offset DllFunctionCall

call eax ; DllFunctionCall

jmp eax

The memory address 0xYYYYYYYY represents the address of the DllFunctionCallStruct. This structure is usually saved as a global variable. The sHandleData field within the DllFunctionCallStruct points to another global variable in memory. The fnAddress field within the DynamicHandles structure is accessed directly via the offset dword_ZZZZZZZZ. If the exported function has not been loaded into memory yet then DllFunctionCall will be invoked, thereby populating the value stored at dword_ZZZZZZZZ, and any sequential calls will directly call the exported function.

In malware, dozens or even hundreds of these wrapper functions can be found. Going through each reference to DllFunctionCall, applying the DllFunctionCallStruct and DynamicHandles structures, labelling the structure and direct address to the fnAddress field, and defining/renaming the function is a lot of work. To get around this cumbersome task I've created a IDA Python script that will perform these monotonous tasks and print out a listing of all the dynamically loaded API used by the binary.

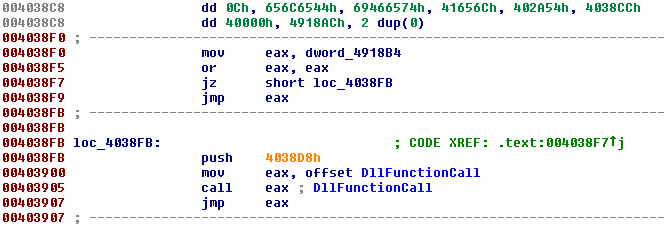

As an example, a VB compiled binary may contain the below undefined section of code (see figure Undefined Code below). Note that IDA Pro was unable to make a function out of this set of instructions, didn’t interpret “push 4038D8h” as an offset within the binary, and didn’t recognize the ASCII string or offset to it starting at virtual address 0x004038CC.

|

| Undefined Code |

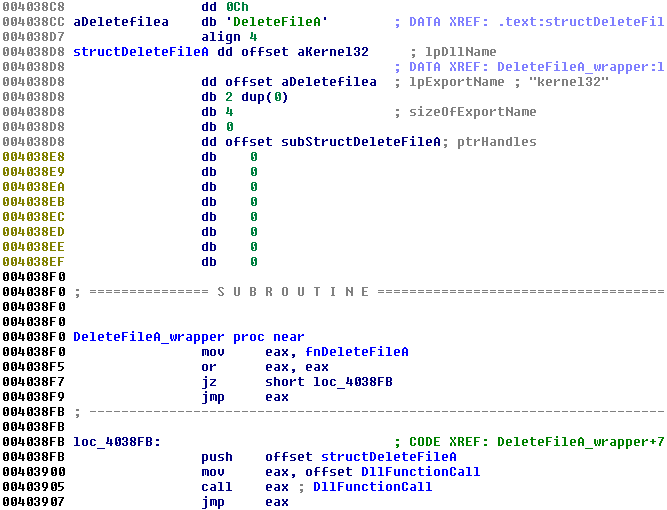

After the IDA Python script runs, the disassembly is cleaned up, a function is defined, the structures are applied, offsets are labeled, strings are defined, and appropriate names are given to the function and global variables. This will be applied to all DllFunctionCall wrapper functions generated by the compiler.

|

| Defined Code |

The script is freely available and comes "as is," depending on your situation it may need to be altered. For example if the VB binary you are analyzing obfuscates the strings associated with library name or export name then the strings will need to be de-obfuscated first.

The script can be downloaded on our Github.