Update: 4/11 we have corrected the detection to Ursnif/Dreambot

This post was authored by Ross Gibb with research contributions from Daphne Galme, and Michael Gorelik of Morphisec, a Cisco Security Technical Alliance partner.

Cisco has noticed an increase in infections by the banking trojan IcedID through our Advanced Malware Protection (AMP) system. Security researchers first reported a new banking Trojan known as "IcedID" [1] in November 2017. At the time of discovery, IcedID was being distributed by Emotet, another well-known banking trojan malware. In late February and throughout March 2018, we noticed an increase in infections from IcedID being detected throughout the AMP ecosystem. Like in November 2017, some of the infections could be traced to Emotet, but this time, many detections could instead be traced to emails with attached malicious Microsoft Word documents containing macros. When the malicious documents are opened and the macros are enabled, Ursnif/Dreambot, another trojan, would be downloaded and executed, which subsequently downloads IcedID. In addition to Ursnif/Dreambot, many of the samples downloaded a second payload, a Bytecoin miner (Bytecoin is a crypto currency similar to bitcoin).

Ursnif/Dreambot is financially motivated malware that is known to download and install additional modules, or other malware families. This Ursnif/Dreambot/IcedID attack was interesting for two reasons:

- The targeted nature of the emails that use spear-phishing techniques to entice victims into opening the malicious Microsoft Word documents.

- The minimalist code injection technique used by IcedID that improves on existing code injection techniques, and is harder to detect.

Figure 1: Malicious document that installs Ursnif/Dreambot and IcedID banker attached to spear-phishing emails

Use of spear-phishing emails

At first, this attack appeared to be similar to the countless malicious Microsoft Word documents with macros that Cisco blocks every day. In this case, when the documents are opened, users are enticed to enable macros in order to view the content. If the user enables macros within the document, an auto-close macro is triggered when the user closes the document that executes mshta.exe (a built-in Windows component) to download and execute a remote script. The remote script launches two instances of PowerShell to download and execute the Ursnif/Dreambot/IcedID and Bytecoin miner payloads.

This attack became more interesting when the targeted nature of the emails and the file names of email attachments were investigated.

Widely distributed malware families that spread over email (like Ursnif/Dreambot) generally send out their malicious messages in high volume. Most end-user security training programs center around helping users identify these kinds of emails, and to be suspicious of any unexpected emails. An attacker sending emails in large volumes has typically chosen email content that applies to a wide range of different recipients, but will not immediately be viewed as suspicious. For example, attackers have recently been using email content such as job applications with attached resumes, shipment delivery notifications with attached tracking information, or notices for payment with attached invoices. In contrast, spear-phishing attacks use emails that are much more targeted at the recipient, and contain information familiar to the recipient. Previously, spear-phishing was primarily used by advanced persistent threat (APT) actors who had specific targets.

Ursnif/Dreambot/IcedID is a clear example of the evolution of spear-phishing from exclusive use by APT actors, to use by malware families with wide distribution. For example, one of the Ursnif/Dreambot distribution emails had the following features:

- The email was sent to an employee of a city in the state of Arkansas.

- The email's subject referenced a meeting relevant to city business.

- The email's body referenced and discussed the meeting, as well as containing names of employees that work at the city.

- The name of the document attached to the email included the name of a civil engineering company local to Arkansas.

A similar example to the one above was found in a malicious email received by an electrical company in Raleigh, North Carolina. The file name of the attached document included the name of an engineering company also local to North Carolina.

Not all examples were as highly targeted to a specific business, but rather targeted users in a similar industry. For example, users with email addresses related to the automotive industry received emails with an attachment file name that referenced the name of a car dealership in Dallas, Texas.

The use of spear-phishing techniques to create emails containing references to people or businesses that the recipient is familiar with makes it more likely that the user will open the attachment and enable the macros within. Since spear-phishing emails require the attacker to create emails for each target, there is a higher cost to the attacker to launch this kind of attack, but will pay off if the attacker invests the time necessary.

Minimalist code injection

Once launched, IcedID takes advantage of an interesting technique to inject malicious code into svchost.exe — it does not require starting the target process in a suspended state, and is achieved by only using the following functions:

- kernel32!CreateProcessA

- ntdll!ZwAllocateVirtualMemory

- ntdll!ZwProtectVirtualMemory

- ntdll!ZwWriteVirtualMemory

IcedID's code injection into svchost.exe works as follows:

- In the memory space of the IcedID process, the function ntdll!ZwCreateUserProcess is hooked.

- The function kernel32!CreateProcessA is called to launch svchost.exe and the CREATE_SUSPENDED flag is not set.

- The hook onntdll!ZwCreateUserProcess is hit as a result of calling kernel32!CreateProcessA. The hook is then removed, and the actual function call to ntdll!ZwCreateUserProcess is made.

- At this point, the malicious process is still in the hook, the svchost.exe process has been loaded into memory by the operating system, but the main thread of svchost.exe has not yet started.

- The call to ntdll!ZwCreateUserProcess returns the process handle for svchost.exe. Using the process handle, the functions ntdll!NtAllocateVirtualMemory and ntdll!ZwWriteVirtualMemory can be used to write malicious code to the svchost.exe memory space.

- In the svchost.exe memory space, the call to ntdll!RtlExitUserProcess is hooked to jump to the malicious code already written

- The malicious function returns, which continues the code initiated by the call tokernel32!CreateProcessA, and the main thread of svchost.exe will be scheduled to run by the operating system.

- The malicious process ends.

Since svchost.exe has been called with no arguments, it would normally immediately shut down because there is no service to launch. However, as part of its shutdown, it will call ntdll!RtlExitUserProcess, which hits the malicious hook, and the malicious code will take over at this point. https://alln-extcloud-storage.cisco.com/ciscoblogs/5ac52bebc03d1.mp4 Video: Identifying and analyzing IcedID’s minimalist injection technique (6:04)

Malware authors are constantly looking for more surreptitious ways to inject code into benign processes. Process doppelganging, a fileless code injection technique, [2] and atom bombing, a technique which uses atom tables for writing into memory of another process, [3] are examples of completely new classes of code injection techniques malware authors have recently found and leveraged. The minimalist process injection technique used by IcedID is an evolution of existing process injection techniques [4], rather than an entirely new class of technique.

Minimalist code injection does offer the following improvements over known techniques:

- Requires only four Windows API calls to achieve code injection.

- Does not require the created process to be created in a suspended state.

- Does not require new threads to be created in the target process.

Using fewer functions and less suspicious process-creation flags makes this minimalist code injection technique more difficult for security solutions to detect.

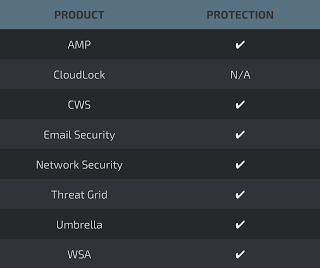

Detection

Cisco AMP for Endpoints' new exploit prevention engine offers protection against both Ursnif/Dreambot and IcedID. While neither Ursnif/Dreambot nor IcedID contain actual exploits, both are detected and blocked by the AMP exploit prevention engine because of suspicious access to memory that each performs. In the case of Ursnif/Dreambot, memory manipulation done by its unpacking routine is detected. In the case of IcedID, when it performs the minimalist memory injection technique, it is detected when it attempts to place the hook on the ntdll!ZwCreateUserProcess function.

Conclusion

The use of spear-phishing emails targeted at specific organizations and industries by Ursnif/Dreambot/IcedID show that widely distributed malware families are adapting to an environment of improved defenses. As detection methods improve, and users become more skilled at identifying suspicious emails, attackers who could once send the same malicious email to all their targets are having to improve their techniques. But the use of the minimalist code injection technique by IcedID shows that attackers are changing their techniques post-infection to better hide and remain on systems that older injection techniques would likely have been detected on.

Coverage

Additional ways our customers can detect and block this threat are listed below.

Advanced Malware Protection (AMP) is ideally suited to prevent the execution of the malware used by these threat actors.

CWS or WSA web scanning prevents access to malicious websites and detects malware used in these attacks.

Email Security can block malicious emails sent by threat actors as part of their campaign.

Network Security appliances such asNGFW,NGIPS, andMeraki MX can detect malicious activity associated with this threat.

AMP Threat Grid helps identify malicious binaries and build protection into all Cisco Security products.

Umbrella, our secure internet gateway (SIG), blocks users from connecting to malicious domains, IPs, and URLs, whether users are on or off the corporate network.

Open Source Snort Subscriber Rule Set customers can stay up to date by downloading the latest rule pack available for purchase on Snort.org.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

Malicious Document

b0457ecdcc1940850af6d858e2f2e91e555a71f250f53b7ba9d4434a81810032

Ursnif/Dreambot

5916b8c0c0668d106ebfcad97eb5c90687c873a732eb61f00e5d7033f8fd85ed

IcedID

Unpacked IcedID binary demonstrating injection

d5164e296c7e7a0c3b2a9e34f07bebcdd0ab7df9ab63ca7dffac6d65e60b0b25

(see hook on ntdll!ZwCreateUserProcess at 0x4016a6)

Additional IcedID binaries

0bd92149834e083320bc5a51f21ac768e26a115c0d589aae22d56ce4c5cf2330

0ca2971ffedf0704ac5a2b6584f462ce27bac60f17888557dc8cd414558b479e

0ea7f227bcbc0b7cd9d1d951a8dfde56f8d18989e4f4c2b0290246e282a14842

107f44919999afc3ddf9c8d1e552ca8463c71ac53fbeaf62ab7de80aba796e15

1f8b4e2ef4c318625447884156be50691555e409242252e504ab15ade5bba4d8

24bde557761930ec48a6573c2f7f538be784652e7c55224ba474e443bd1d8c55

4c851e40390df6021c8396c9141d50b52d2dc027586a2edb5f682707987adfad

64f3abc5b0b65cd4bca68b3200cf2d645d3557fbc6dfe36a127734c3ce436860

693599aa847dece5b5cfcca5d545fe5f3f87e5acd10ed807e731741ee306ab4c

70e2782079e95e312d7e2de69a6ac0f56874caaf021e1e3f45750f62b7d386ff

7700fe76b40bc4a0f1b93ae32b9f34c595ef0e2886632e26ebf5f43be1aea63c

7c89b72451f7361cc3f120d0c38287fe5acc9f6e8210279cfe09318d6fe92869

8408fd2fab0b7fce952d6338164040eeb5ae910cbf355ea41f798e04998507bc

84a664fd2ca39c0a7258bed6f8d3e707bcf6c597bb4f94401940b4e005578dae

84ecae42c9c88ae5c2bdf51d546421b02d06bcf57b48b2abafdbd38d81bacfa8

8ce7889ca54f6c480ee3534fbeb2383779583e258b1e4ac5b851b578a40bc31f

9426acf9edf6479374905b743ab0a550183c2b1869af1a8da2bb69a25e2cad1e

995de239c8160435f50675d42a20cf773e6a3e10c8812f4d680114170e07f914

9b5930266d5494553f3801d62d7ef20dc866fadda0ee654da85e01042aa91338

a5779442a31d66407cec78d1d58832a847d5929587cb22b8ad7459f4a28deeef

a88f9196456011043bd404377146f7443550a6f11a08fcfac29a55273bd75509

da1e9b6766b9a6445c77ac522a73cc763be2f2500fb1ed8af63e2c47e0f884fb

e899b27d0e241914cba36c43dfb686bf008237d10beff9114f9aad04b7c919de

ed578c318be8a671b4b3d23db9b3fc4bd031befe490543d60e6bcf0759fc51c5

ffc7479a186f1101a9e7800d8830d235ba6797dc293ade57864f2db26fa58c0f

Network

efoijowufjaowudawd[.]com

86.123.64.43

Scheduled task

The existence of a scheduled task at:

C:\Windows\System32\Tasks\Update

The "Exec" action within the scheduled task will take the command line argument "/i" and the path of the executable will be in the APPDATA directory. For example,

<Exec>

<Command>"C:\Users\Administrator\AppData\Local\Microsoft Help\\restewbes.exe"</Command>

<Arguments>/i</Arguments>

</Exec>

References

[1] https://securityintelligence.com/new-banking-trojan-icedid-discovered-by-ibm-x-force-research/

[2] https://www.blackhat.com/docs/eu-17/materials/eu-17-Liberman-Lost-In-Transaction-Process-Doppelganging.pdf

[3] https://blog.ensilo.com/atombombing-brand-new-code-injection-for-windows

[4] https://www.endgame.com/blog/technical-blog/ten-process-injection-techniques-technical-survey-common-and-trending-process