- QR codes are disproportionately effective at bypassing most anti-spam filters, as most filters are not designed to recognize that a QR code is present in an image and decode the QR code. According to Cisco Talos’ data, roughly 60% of all email containing a QR code is spam.

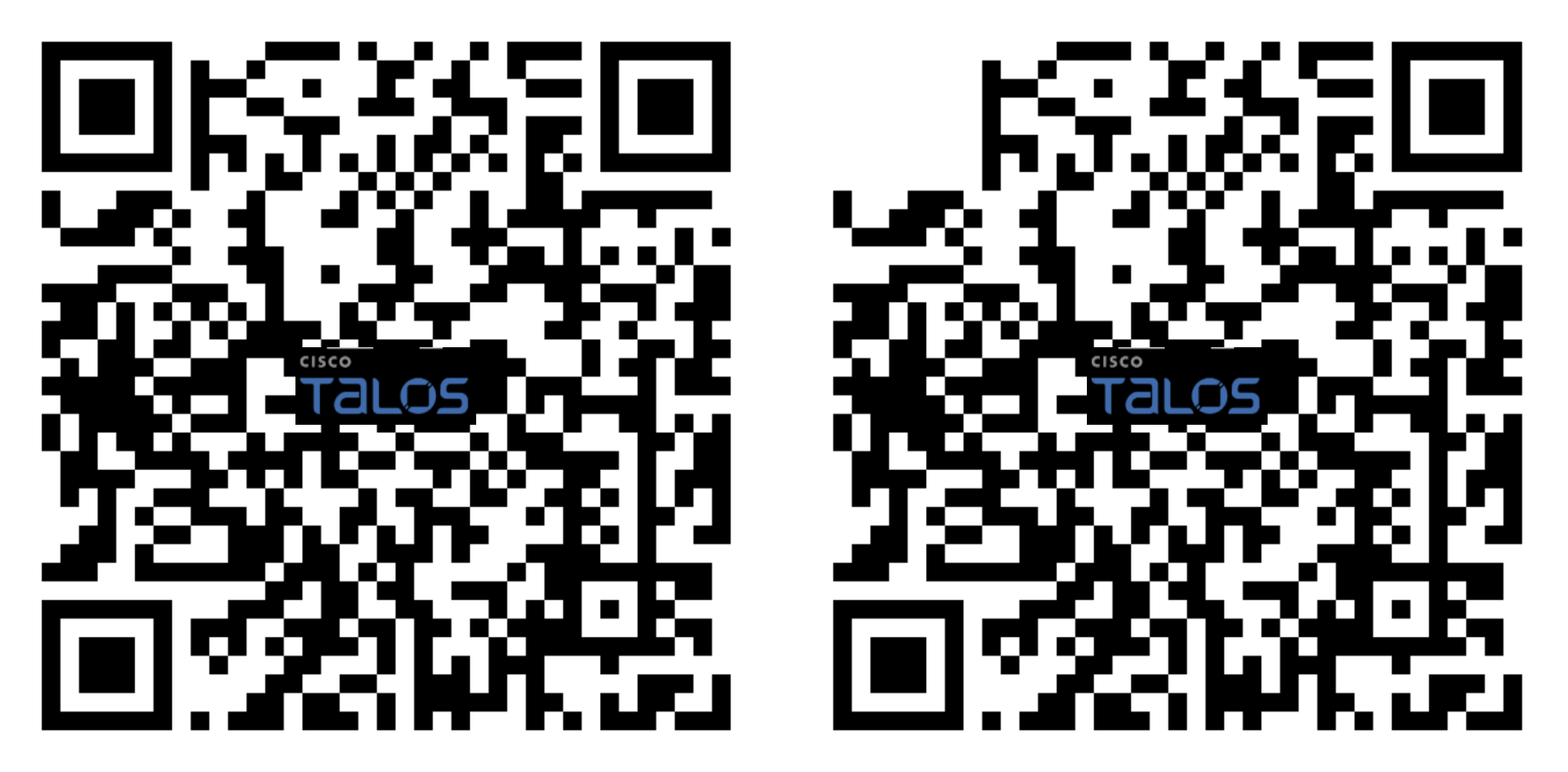

- Talos discovered two effective methods for defanging malicious QR codes, a necessary step to make them safe for consumption. Users could obscure the data modules, the black and white squares within the QR code that represent the encoded data. Alternatively, users could remove one or more of the position detection patterns — large square boxes located in corners of the QR code used to initially identify the code's orientation and position.

- Further complicating detection, both by users and anti-spam filters, Talos found QR code images that are “QR code art.” These images blend the data points of a QR code seamlessly into an artistic image so the result does not appear to be a QR code at all.

Prior to 1994, most code scanning technology utilized one-dimensional barcodes. These one-dimensional barcodes consist of a series of parallel black lines of varying width and spacing. We are all familiar with these codes, like the type you might find on the back of a cereal box from the grocery store. However, as the use of barcodes increased, their limitations became problematic, especially considering that a one-dimensional barcode can only hold up to 80 alphanumeric characters of information. To eliminate this limitation, a company named Denso Wave created the very first “Quick Response“ codes (QR codes).

QR codes are a two-dimensional matrix bar code that can encode just over 7,000 numeric characters, or up to approximately 4,300 alphanumeric characters. While they can represent almost any data, most frequently we encounter QR codes that are used to encode URLs.

Quantifying the QR code problem

Talos extracts QR codes from images inside email messages and attached PDF files for analysis. QR codes in email messages make up between .01% and .2% of all email worldwide. This equates to roughly one out of every 500 email messages. However, because QR codes are disproportionately effective at bypassing anti-spam filters, a significant number find their way into users’ email inboxes, skewing users’ perception of the overall problem.

Also, of course, not all email messages with a QR code inside are spam or malicious. Many email users send QR codes as part of their email signature, or you may also find legitimate emails containing QR codes used as signups for events, and so on. However, according to Talos’ data, roughly 60% of all email containing a QR code is spam.

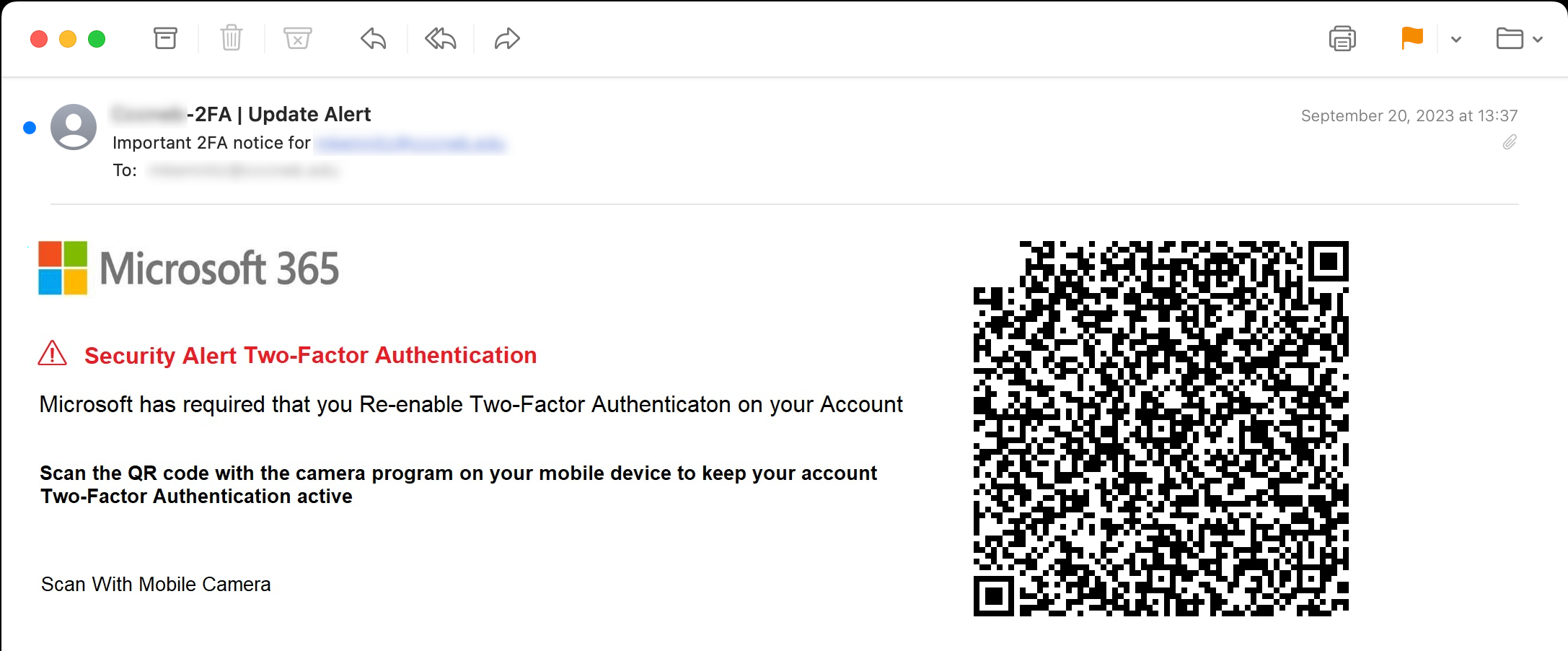

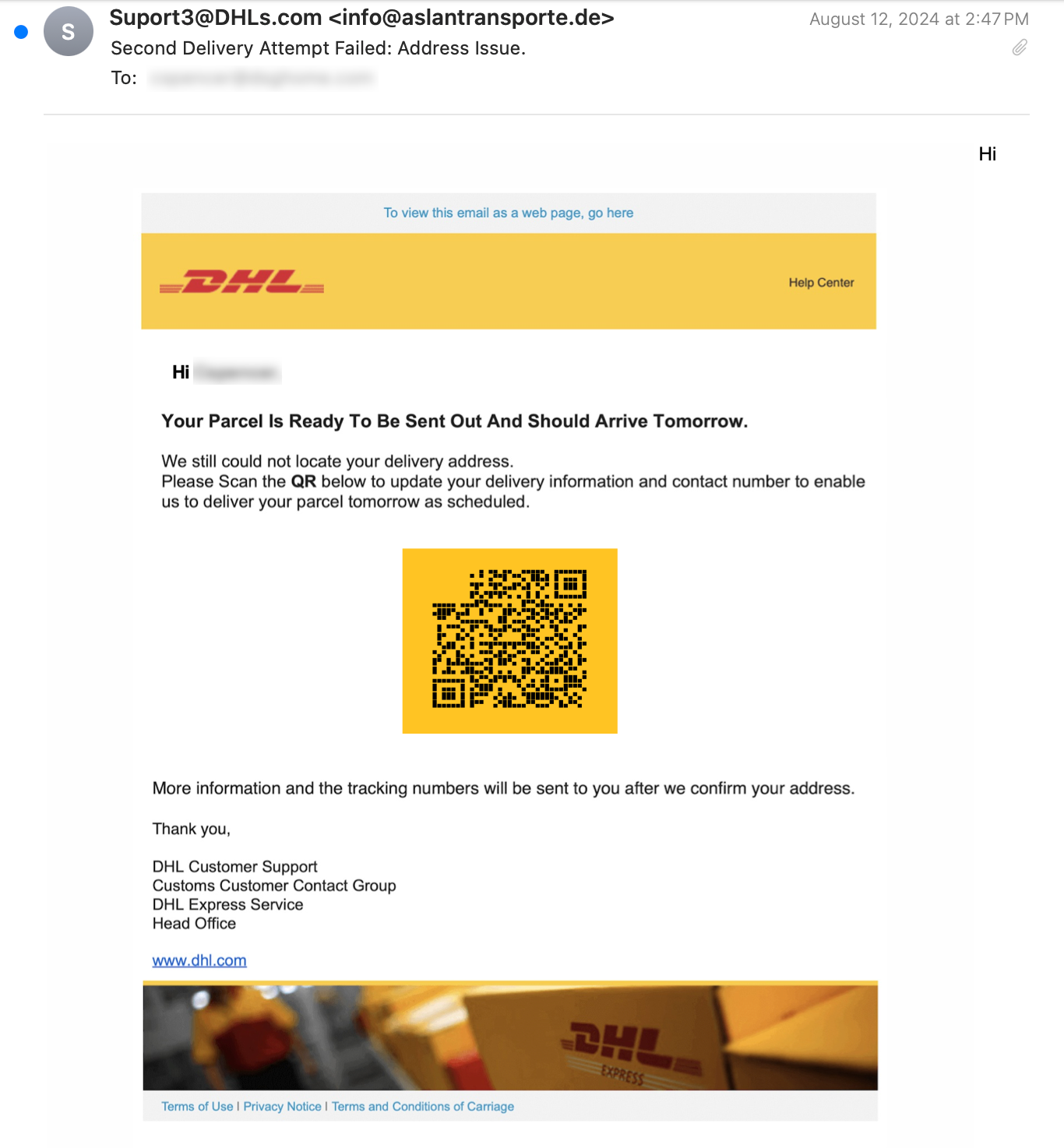

Truly malicious QR codes can be found in a much smaller number of messages. These emails contain links to phishing pages, etc. The most common malicious QR codes tend to be multifactor authentication (MFA) requests used for phishing user credentials.

One of the problems that defenders may encounter when dealing with users’ scanning of QR codes received via email, assuming the user’s device is not connected to the corporate wi-fi, is that subsequent traffic between the victim and the attacker will traverse the cellular network, largely outside the purview of corporate security devices. This can complicate defense, because few/no alerts from security devices will notify security teams that this has occurred.

Why are malicious QR codes hard to detect?

Because QR codes are displayed in images, it can be difficult for anti-spam systems to identify problematic codes. Identifying and filtering these messages requires the anti-spam system to recognize that a QR code is present in an image, decode the QR code, then analyze the link (or other data) present in the decoded data. As spammers are always looking for innovative ways to bypass spam filters, using QR codes has been a valuable technique for spammers to accomplish this.

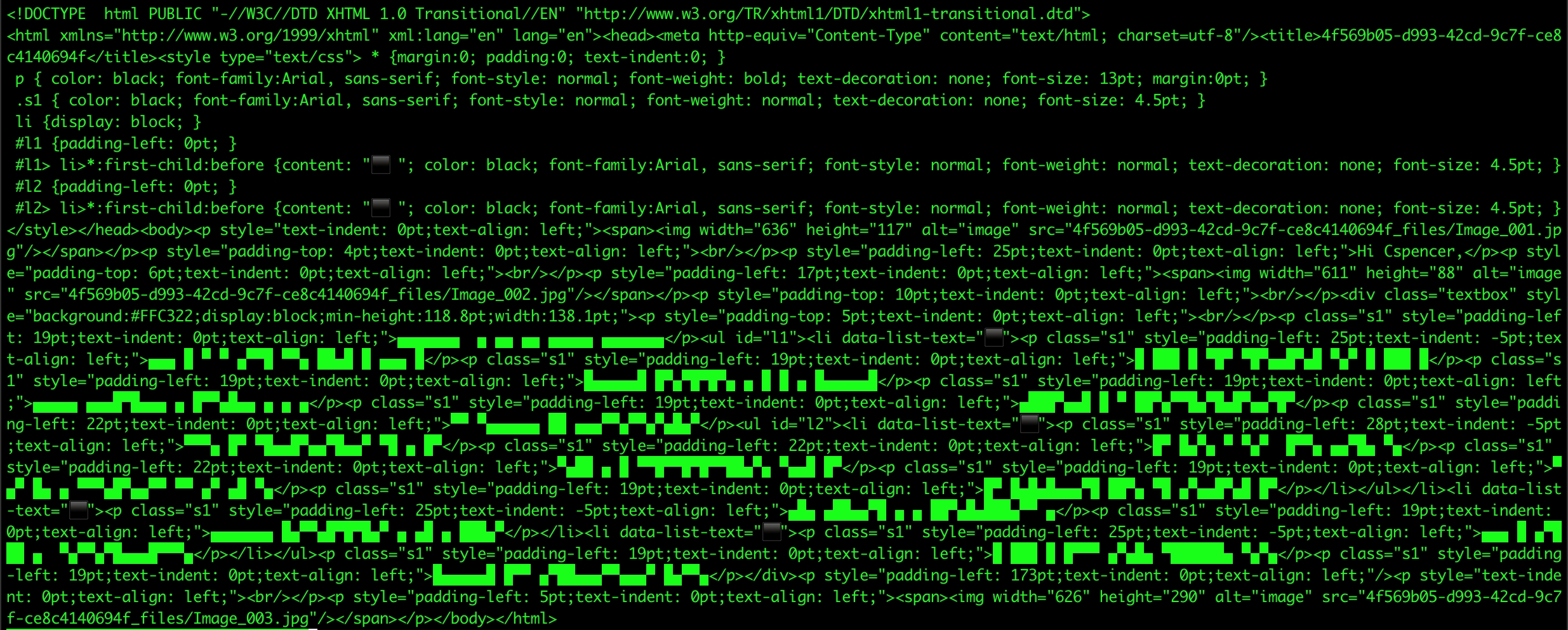

As anti-spam systems improve their capability to detect malicious QR codes in images, enterprising attackers have instead decided to craft their QR codes using Unicode characters.

The graphical parts of the image are contained within a PDF file. The PDF metadata indicates it was created from HTML using the tool wkhtmltopdf. Converting the PDF back into HTML shows the Unicode that is being used to construct the QR code.

Defanging QR codes

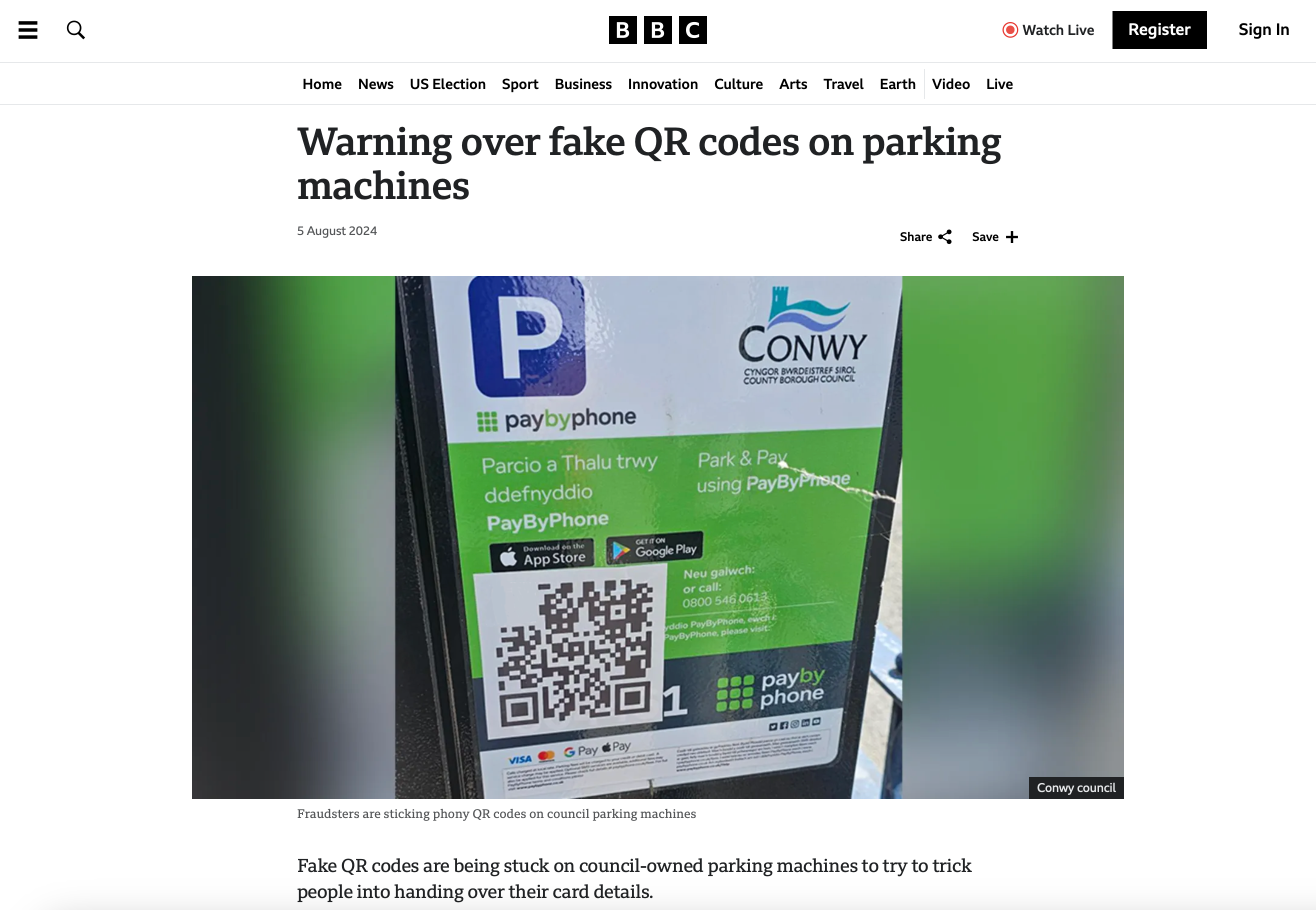

When sharing malicious URLs, it is common to change the protocol from “http” to “hxxp”, and/or to add brackets (“[]”) around one of the dots in the URL. This makes it so browsers and other applications do not render the link as an active URL, ensuring that users do not inadvertently click on the malicious URL. This is a process known as “defanging.” Unfortunately, while defanging URLs is commonplace, many people do not defang malicious QR codes. For example, below is a news article from BBC about criminals who put QR code stickers on parking meters in an attempt to harvest payment credentials from unsuspecting victims.

The problem is that these QR codes can still be scanned, taking visitors to whatever malicious link that the QR code encoded. To make malicious QR codes safe for consumption, they should be defanged.

There are a couple of different ways to do this. One way is to obscure the data modules, the black and white squares within the QR code that represent the encoded data. This is where the data that the QR code represents is located. However, based on Talos’ own research, a far easier way to defang a QR code is to remove one or more of the position detection patterns (a.k.a. finder patterns). These are the large square boxes located in three of the four corners of the QR code, which are used by the QR code scanner to initially identify the code's orientation and position. Removing the position detection patterns renders a QR code unscannable by virtually all scanners. Additional details on how this is achieved, will be covered later in the blog.

Be careful what you scan!

For years, security professionals have encouraged users not to click on unfamiliar or suspicious URLs. These URLs could potentially lead to phishing pages, malware or other harmful sites. However, many users do not exercise the same care when scanning an unknown QR code as they do when clicking on a suspicious link. To be clear, scanning an unknown/suspicious QR code is equivalent to clicking on a suspicious URL.

To complicate the situation even more, there are QR code images that are “QR code art.” These images blend the data points of a QR code seamlessly into an artistic image so the result does not appear to be a QR code at all. The potential danger with QR code art images is that a user could conceivably be tricked into scanning a QR code art image with their camera, and then inadvertently navigate to the linked content without realizing it.

How to protect yourself from malicious QR codes

QR codes have become ubiquitous, appearing in email, on restaurant menus, at public events, on retail packaging, in museums, and even public parks and trails. The perfect defense is to avoid scanning any QR codes; however, it can be difficult to avoid scanning these entirely, so users must exercise caution. Scanning a QR code is essentially the same as clicking on an unknown hyperlink, but without the ability to see the full URL beforehand.

There are several QR code decoders freely available online. Typically, if you can save a screenshot of the QR code, you can upload this image to one of these decoders, and the QR code decoder will tell you what data was encoded inside the QR code. This will allow you to more closely inspect the link. You can also choose to navigate to that URL using an application like Cisco Secure Malware Analytics (Threat Grid). This will allow you to view the content behind the URL from a safe place, without jeopardizing the security of your desktop or mobile device. Products such as Cisco Secure Email Threat Defense can prevent emails containing malicious QR codes from ever reaching your inbox. As always, never enter your username and password into an unknown site. It is better to navigate directly to anywhere you wish to login, rather than clicking on a URL presented to you from an unknown third party.