What does your autonomy mean to you?

- After the recent Supreme Court ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women's Health Organization, the use of third-party apps to track health care has recently come under additional scrutiny for privacy implications.

- Many of these apps have privacy policies that state they are authorized to share data with law enforcement investigations, though the exact application of those policies is unclear.

- The use of health-tracking apps and wearable tech is rising, raising questions around the application of the 14th Amendment’s equal protection clause and HIPAA rules as to who can and cannot collect and share health care information.

It’s become second nature for many users to blindly click on the “Accept” button on an app or website’s privacy policy and terms of service. But in the wake of the U.S. Supreme Court’s ruling in Dobbs v. Jackson Women’s Health Organization that reversed previous interpretations of the 14th amendment on privacy from Roe v. Wade, users of sensitive health apps need to be mindful of the kinds of data these apps keep, sell and share. It is a privacy ruling at its core, with the decision raising concerns about the government’s ability to access our personal and private information. Today’s digital surveillance infrastructures, coupled with new and existing laws, digital health histories are nearly impossible to protect.

The use of health data tracking applications and wearable tech has rapidly increased in the past several years. These apps track a hodgepodge of data, from heart rate and blood oxygen level, to when and where a user works out, to what a user eats. Some of these fitness applications even track more sensitive data like sexual activity, body composition using progress photos, and sleep cycles. Blood glucose levels can be tracked continuously using a wearable sensor and app rather than routinely timed finger pricks.

Privacy policies are only so private

Although there are stringent laws regarding the use of personally identifiable information tied to health records, there are grey areas in the way this legislation applies to the data collected by healthcare apps. Additionally, if the servers of these apps are breached or otherwise compromised, there may be no liability to the app. This breached data is often sold on readily accessible marketplaces. But even if there’s no breach or illicit use of this information, apps and their creators can still learn a great deal about users.

When health data collected by these apps is combined with other datasets like location data and what is available on social media profiles, advertisers, law enforcement agencies and more can craft a shockingly comprehensive view into the user’s life. In some instances, this inferred profile can be used for nefarious purposes, even resulting in criminal charges. Even prior to recent rulings, police in Nebraska launched an investigation using Facebook messages, eventually leading to criminal charges. In July 2021, a Catholic publication used location data tied to Grindr activity, purchased from a data aggregator, to allege that a high-ranking bishop was potentially gay. This allegation ultimately led to the bishop’s resignation.

Some of the most sensitive data tracked by users of health apps is in period and pregnancy tracking apps. These apps track things like period timing and symptoms, user-provided notes and comments, ovulation periods for those who are trying to get pregnant, and fetal growth process throughout pregnancy. Many of these apps state that they do not sell or share user data in their privacy policies. However, there are often exceptions for law enforcement requests. In the aforementioned case in Nebraska, Meta, Facebook’s parent company, complied with the investigation by giving law enforcement data on two people involved in compliance with its privacy policy and regulations.

PII on especially sensitive apps

Since the ruling, there have been continuous calls for users to delete apps tracking this information. Although laws like HIPAA in the United States stringently regulate the use and sharing of health records by traditional providers, these laws do not apply in the same manner to third-party health apps. These apps function as what is called a “designee,” and in some cases, can share data provided by users without their direct consent. This is because health tracking apps are considered “non-covered entities.”

HIPAA only applies to covered entities, defined as health plans, healthcare clearinghouses, and specifically defined providers and associates. Apps typically do not fall within these definitions unless they are provided by a user’s insurance company or healthcare provider. Because HIPAA does not apply and there is limited legislation preventing it, these apps are free to sell and share your personal health data in a way that your doctor cannot.

Privacy watchdog organizations fear that, with this ruling, the laws around data sharing could be loosened. The right to privacy, interpreted to be provided by the 14th Amendment (along with others) has been used as precedence for a myriad of other laws outside of women’s reproductive rights, such as the legalization of same-sex marriage in the U.S. Privacy watchdogs are speculating that undermining these rights could allow for the sharing of personally identifiable health records to be used to determine insurance rates, with higher rates for individuals deemed to be high risk, or even for health records to be shared with current or prospective employers. In a world with no regulations against the sharing of health records on health apps, your medical diagnoses or level of risk inferred from your nutrition or workout trackers, could be used against you.

Without legislation preventing the sharing of your health data, app privacy policies are the only barrier to your data being shared or sold without your consent. These privacy policies tend to vary between individual apps, however.

What some popular apps’ policies say

What to Expect is one of the most popular pregnancy apps currently available on all platforms. This app is widely used by users who are either currently pregnant or trying to become pregnant, ranked No. 52 in Health and Fitness on the Apple app store, with nearly 300,000 positive reviews. In addition to data actively provided to the app, the app’s Privacy Policy states several other layers of personally identifiable information (PII) are collected, including the user’s expected due date, any photographs posted to the app, demographic information like gender and age, contact details, location information and “any views or opinions you provide to us.”

However, the app’s policies also state it will process that information when “conducting investigations where necessary” and in “compliance with applicable law.” The policy also states:

"We may disclose your User Information to legal and regulatory authorities; our external advisors; parties who Process User Information on our behalf (“Processors”); any party as necessary in connection with legal proceedings; any party as necessary for investigating, detecting or preventing criminal offenses; any purchaser of our business; and any third party providers of advertising, plugins or content used on the Services. Other apps and services have overhauled and strengthened their privacy and data-sharing policies in response to changing abortion laws."

Flo, a popular period tracking app, recently announced a new “anonymous” mode that will allow users to completely remove their personal and device information from the app and leave the company without any access to their data should a law enforcement agency request it.

"If Flo were to receive an official request to identify a user by name or email, Anonymous Mode would prevent us from being able to connect data to an individual, meaning we wouldn't be able to satisfy the request," the company’s CEO said in an email to users announcing the new features.

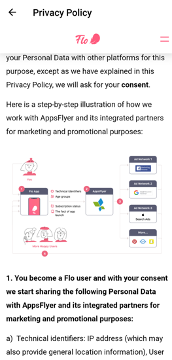

For any users not using Anonymous mode, Flo’s default privacy policy permits the app to share PII with a third-party advertising company, AppsFlyer, which then uses that information to generate curated ads on several other platforms, such as the social media app Snapchat and Google sites.

Astrology-focused menstrual tracking app Stardust also announced earlier this year that it changed its privacy policy to clarify that it would not provide user data if requested by law enforcement. And Clue, a European-based app that tracks menstrual cycles, and pregnancies and offers its own form of birth control, says it will not cooperate with any U.S.-based law enforcement investigations.

For other, less-recognized apps, policies vary greatly and leave the door open for data-sharing with law enforcement if users are not careful about investigating their privacy policies and information-sharing agreements.

On the Android app store, searching for “Period tracker” surfaces several non-mainstream apps as top results, such as “Period Calendar Period Tracker.” That app offers users predictions on when users’ next period will begin, peak ovulation times and any symptoms they’re experiencing on specific days and times.

The app’s privacy policy states that it will "share information with law enforcement agencies, public authorities, or other organizations if We’re [sic] required by law to do so or if such use is reasonably necessary. We will carefully review all such requests to ensure that they have a legitimate basis and are limited to data that law enforcement is authorized to access for specific investigative purposes only."

The app’s Android store page does advertise that it doesn't share any data with other companies or organizations, though some of the service providers they partner with might sell it.

The store page for the app also contains an image claiming that it is “Verified by Privacy International,” a U.K.-based privacy-focused non-profit organization. Period Calendar Period Tracker was mentioned in a 2019 study listing which period-tracking apps did or did not share data with Facebook — at the time, the app did not share information with Facebook. However, a representative from Privacy International told Talos the organization has no relationship with the app, nor does it verify or certify certain apps based on their privacy policies.

Things to consider when downloading health care-related apps

- As data privacy law changes rapidly, users should be more mindful of the types of information and data they share with these apps. Outside of switching to a traditional pen-and-paper calendar method, there are a few tips users can follow when considering using an app that tracks health data of any kind, particularly the kinds of sensitive data tracked by period or pregnancy tracking app:

- Carefully evaluate privacy policies before downloading and using an app, and don’t hesitate to reach out to listed contacts for additional information. Be aware that if an app’s privacy policy does not include a section titled “Notice of Privacy Practices for Protected Health Information," HIPAA does not apply, and there is limited legislation preventing the app from selling or sharing your health data.

- Be mindful about the types of information you share with these apps and evaluate your level of risk were this information to become public. Ensure you are only sharing information with these apps that you are comfortable with potentially becoming public without your consent.

- If allowed by the app, opt out of all data collection and information sharing. Many apps will offer this option because of GDPR rules in Europe or California’s recently passed California Consumer Privacy Act.

- Only download apps from trusted stores and trusted developers.

- Use anonymous modes if offered by the app.

Note: Representatives from Period Calendar Period Tracker and What to Expect did not respond to a request for comment via emails sent to their publicly listed contact information in the respective apps’ privacy policies.