In ancient Greek mythos, the mighty Hercules faced a seemingly insurmountable challenge when he encountered the Lernaean Hydra. This fearsome serpent had a terrifying ability: For every head that Hercules severed, two more would spring forth, creating a never-ending cycle of regrowth and renewal.

Much like the Hydra, modern ransomware gangs present society with a daunting task. When law enforcement manages to take one adversary or low-level member off the streets, the victory is often short-lived. In the hidden depths of these criminal organizations, the heads — or leaders — remain shrouded in shadow, orchestrating their operations often with impunity.

And so, as one member falls, two more may rise to take their place, perpetuating an enduring saga of illicit activity that are the challenges of our time: the ransomware ecosystem. A landscape where affiliates tend to move from ransomware group to ransomware group, following the money, bringing their skills and tools with them to conduct new attacks.

In this blog, we’ll explore the recent law enforcement takedown of LockBit, a group who previously held the title of the number one most deployed ransomware variant for two years running. Just seven days after the takedown, LockBit claimed to resume their operations.

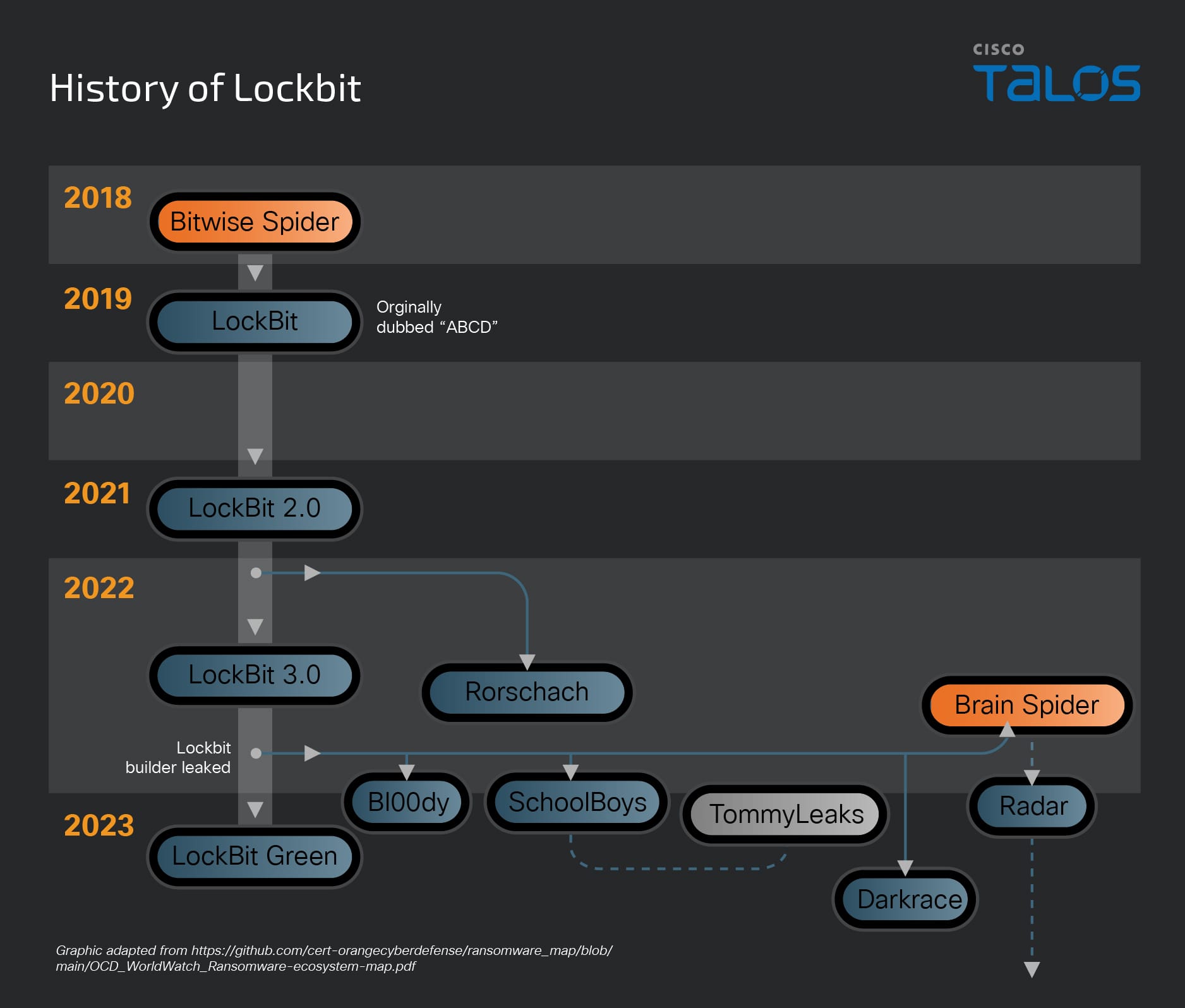

The History of LockBit

LockBit emerged around 2019. Since then, it has continually evolved and innovated to update their ransomware and build their RaaS program.

For the past two years, LockBit ransomware operations accounted for over 25 percent of the total number of posts made to data leak sites. CISA’s assessment is also that LockBit has been the most deployed ransomware variant in recent years.

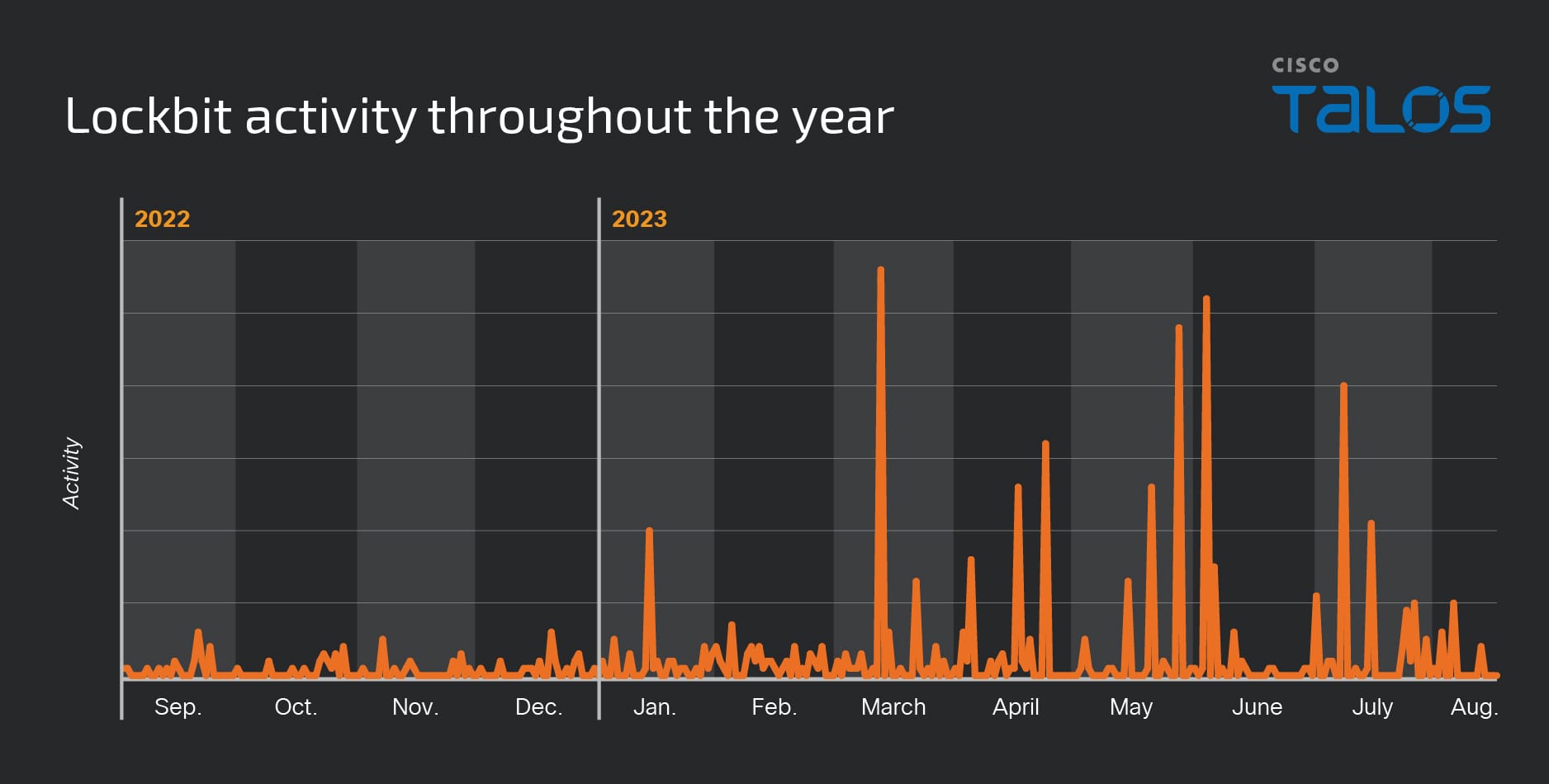

As we wrote in the 2023 Talos Year in Review report, posts made to the group’s data leak site ebbed and flowed from September 2022 to August 2023. Detections of LockBit activity appear to spike in March, partially coinciding with LockBit’s deployment against vulnerable instances of the printer management software PaperCut, where it has remained consistently high.

The Collaboration Trend

For the past two years, Talos researchers have written about a growing ransomware trend, wherein actors are increasingly collaborating with each other and sharing tools and infrastructure (aka the affiliate model).

For example, Talos recently reported on how the GhostSec and Stormous ransomware groups are jointly conducting double extortion ransomware attacks on various business verticals in multiple countries. The two groups have started a new ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) program STMX_GhostLocker, providing various options for their affiliates.

We are seeing more diversified groups employing multiple encryption programs, as well as less sophisticated actors “standing on the shoulders” of giants by using leaked ransomware code. Some players are exiting the game altogether, but not before selling their source code to the highest bidder. This is posing significant challenges to the security community, especially when it comes to attributing attacks.

In the case of LockBit, this was also a group that operated as a RaaS model. They recruited affiliates by offering them shares of profits and encouraging them to conduct ransomware attacks using LockBit’s tools and infrastructure. These affiliates were often unconnected, and as a result, there were many variations in the attacks that used LockBit ransomware.

Notably, the LockBit ransomware group posted on a Russian-speaking dark web forum in December 2023 offering to recruit ALPHV (BlackCat) and NoEscape ransomware affiliates and any of the ALPHV developers, after the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI)’s announcement of a disruption campaign against the ALPHV ransomware operation.

Operation Cronos

The NCA, working closely with the FBI and supported by international partners from nine other countries, covertly investigated LockBit as part of a dedicated taskforce called Operation Cronos.

On Feb. 20, 2024, after infiltrating the group’s network, the NCA took control of LockBit’s primary administration environment. This environment enabled affiliates to build and carry out ransomware attacks, as well as host the group’s public-facing leak site on the dark web, which was used to threaten the publication of data stolen from victims.

The technical infiltration and disruption were only the beginning of a series of actions against LockBit and their affiliates. In wider actions coordinated by Europol, at least three LockBit affiliates were arrested in Poland and Ukraine, and more than 200 cryptocurrency accounts linked to the group have been frozen.

The Return

Seven days after the operation, messages and leak information was published on a new LockBit page. Here are screenshots of their leak site taken daily from Feb. 27 – March 4, with a huge increase of cards on March 3.

The site lists both pre- and post-takedown victims, suggesting LockBit may not have lost access to their entire dataset or infrastructure.

Of particular interest is the fbi.gov card in the lower right corner that links to a lengthy writeup (in English and Russian), stating what LockBit thinks happened during the operation. They talk about lessons learned, speculations and discredit the law enforcement agencies. Talos believes the operation was carried out by the NCA, not the FBI, as LockBit stated.

A recurring theme

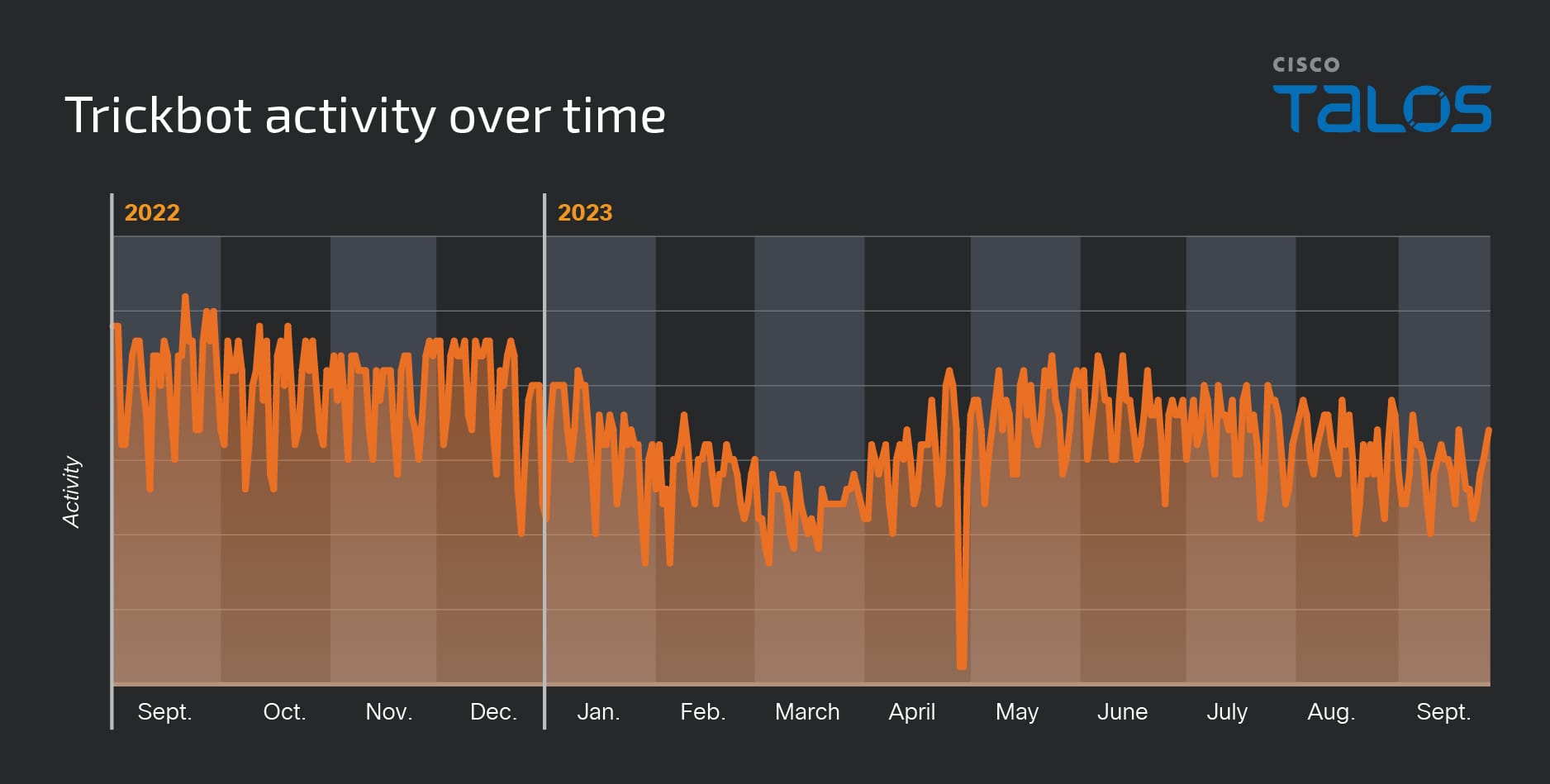

While LockBit is currently dominating the headlines, we’ve seen similar stories before following takedown attempts. For example, the commodity trojan Trickbot had its infrastructure dismantled in February 2022.

However, Talos telemetry picked up Trickbot activity throughout 2023, as covered in our Year in Review.

Still open for business

Talos has intelligence that Lockbit is still accepting affiliates into their program.

Does this mean that law enforcement operations are pointless? Far from it. Takedown attempts such as Operation Cronos severely disrupt their operations, and forces ransomware operators to change their attacks. The operation against LockBit doesn’t appear to have inflicted the final blow against the ransomware group, but it has wounded them.

We also know that law enforcement was able to obtain troves of intelligence through their operation. That intelligence will only serve to be useful in further disruptions, undermining Lockbit's growth. Therefore, if you put Lockbit into a market perspective, they appear to be quite exposed.

Crucially, as with the case of LockBit, decryption tools can be released so that victims of ransomware can gain access to their systems again. In January Talos obtained executable code capable of decrypting files affected by the Babuk Tortilla ransomware variant, allowing Talos to extract and share the private decryption key used by the threat actor.

Therefore, it’s important not to view this operation as a “one and done” effort. Sustained, targeted approaches from law enforcement and the defender community can and do have a significant impact. For example, following the FBI’s actions against BlackCat/ALPHV, the group reportedly denied an affiliate a $22 million ransomware payment before subsequently going out of business in early March, as Brian Krebs wrote about on his website a few days ago.

Azim Khodjibaev from Talos’ threat interdiction and intelligence organization team discusses the ebs and flows of ransomware groups after a takedown in the episode of Talos Takes below. This episode was recorded in 2022 after a separate law enforcement operation to disrupt LockBit.

The lucrative affiliate model

One of the major issues when tackling ransomware crime is the nature of the affiliate program, with actors often working for multiple RaaS outfits at a time. In underground forums, we are seeing increased advertisements by RaaS groups showcasing their affiliate programs and offering profit shares. They can offer large profits, as threat actors can conduct multiple campaigns using the encryption programs that are offered or distributed.

In the case of the GhostSec group, they have a business model that offers affilates three different options: a paid version, a free version and a version that allows actors who don’t want to become a member ransomware gang but would like to publish victim data on their leak site.

We are also seeing multiple groups working together, sharing their malicious tooling with each other, then falling out, and then building trust back up with each other, adding to the difficulty in attributing attacks. Here are Talos’ Nick Biasini and Matt Olney talking about the impact of leaked ransomware code, where Matt describes the situation as “The Real Housewives of Eastern Europe:”

Fundamentally, ransomware continues to be hugely profitable and widespread. In the last quarter, the Talos Incident Response team responded to ransomware incidents involving Play, Cactus, BlackSuit and NoEscape ransomware for the first time, and there was a 17% rise in ransomware incidents in this quarter.

In the end, Operation Cronos may have disrupted LockBit’s operations temporarily with valuable assets gained, a weaker market position for the group, and a few affiliates are now sitting in jail. However, the Hyrdra’s roots run deeper, and this is why we may continue to see LockBit activity throughout the course of the year.

Where to go from here

Like Hercules who outwitted the Hydra with a blend of strength and strategy, our law enforcement’s relentless efforts are essential and commendable. It’s going to take persistent, strategic efforts to significantly damage RaaS operations and weaken the regenerative power of these gangs. Arrests at the top will be a key part of this. In the case of LockBit, it appears as though the leaders of the group have evaded arrest on this occasion.

At the very same time the people of Lerna (or us, the private defenders), need to pay attention to the entire threat landscape. We can’t rely on just Hercules to take them down. Just like we can’t be sure there is just a single Hydra.

Read more about the recent ransomware operations Talos Incident Responders engaged in.