The post was authored by Mariano Graziano.

Executive Summary Attacks have grown more and more complex over the years. The evolution of the threat landscape has demonstrated this where adversaries have had to modify their tactics to bypass mitigations and compromise systems in response to better mitigations. Code-reuse attacks, such as return-oriented programming (ROP), are part of this evolution and currently present a challenge to defenders as it is an area of research that has not been studied in depth. Today, Talos releases ROPMEMU, a framework to analyze complex code-reuse attacks. In this blog post, we will identify and discuss the challenges and importance of reverse engineering these code-reuse instances. We will also present the techniques and the components of the framework to dissect these attacks and simplify analysis.

Code-reuse attacks are not new or novel. They've been around since 1997 when the first ret2libc attack was demonstrated. Since then, adversaries have been moving towards code-reuse attacks as code injection scenarios have gotten much more difficult to successfully leverage due to the increasing number of software and hardware mitigations. Improved defenses have resulted in more complex attacks being developed to bypass them. In recent years, malware writers have also started to adopt return-oriented programming (ROP) paradigms to hide malicious functionality and hinder analysis. For readers who are not familiar with ROP and want to learn more, we invite you to please read Shacham's formulation.

Unfortunately, the analysis of code reuse attacks, such as ROP, has been completely overlooked. While there are a small number of publicly available examples that demonstrate how complex these attacks can be, the trend is clear that adversaries will continue to leverage these types of attacks in the future. For defenders, the general lack of tooling available to help dissect these threats was one of the primary motivations for developing ROPMEMU.

The proposed framework adopts a set of different techniques to analyze ROP chains and reconstruct their equivalent code in a form that can be analyzed by traditional reverse engineering tools. In particular, it is based on memory forensics (as its input is a physical memory dump), code emulation (to faithfully rebuild the original ROP chain), multi-path execution (to extract the ROP chain payload), control flow graph (CFG) recovery (to rebuild the original control flow), and a number of compiler transformations (to simplify the final instructions of the ROP chain). Throughout the post, we test ROPMEMU against Chuck, a persistent return oriented programming (ROP) rootkit.

ROPMEMU is the first step in enabling the automated analysis of code-reuse attacks. As this is an ongoing area of research and ROPMEMU is research prototype, it does lack some functionality to operate on generic inputs and to cope with all possible code-reuse instances. However, we believe it can be a valuable tool during investigations dealing with such threats as we continue to research and develop this framework further.

ROPMEMU has been published at the 11th Asia Conference on Computer and Communications Security (ASIACCS) and the paper can be downloaded here.

ROP 101 The main focus of memory forensics is to find evidence of intrusion in physical memory. Evidence commonly involves artifacts that have been created or injected into memory via malicious components. Volatility plugins like psxview and malfind are good examples of tools that help identify artifacts of compromise or intrusion in memory dumps .

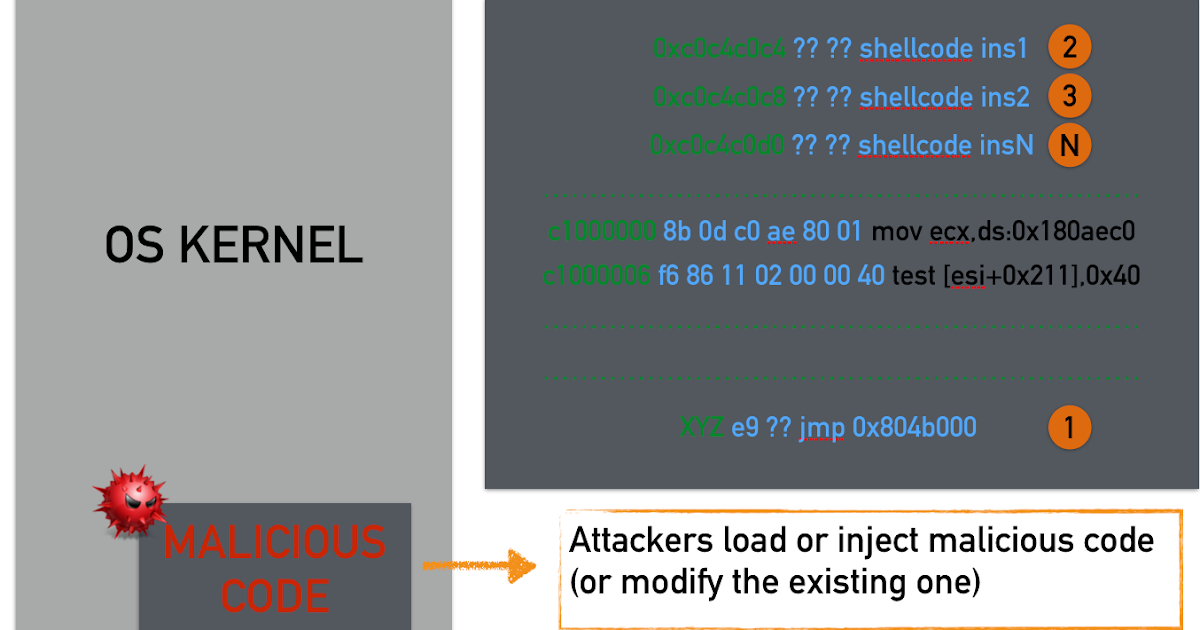

For years, attackers have injected code and hijacked the normal control flow of the targeted application or operating system.In response to these types of attacks, the community developed tools to identify when these types of attacks might have occurred. A typical code injection scenario is illustrated below.

In the illustration above, we see that our shellcode is arranged in memory as one contiguous block that we jump to using a trampoline (step 1). Modern operating systems typically deploy protections or mitigations that make shellcode execution in the data region impossible and in general, code injection attacks nowadays are infeasible. For this reason, offensive researchers have devised new techniques to bypass such countermeasures. Specifically, in a ROP attack the situation is quite different compared to the classic code injection attacks:

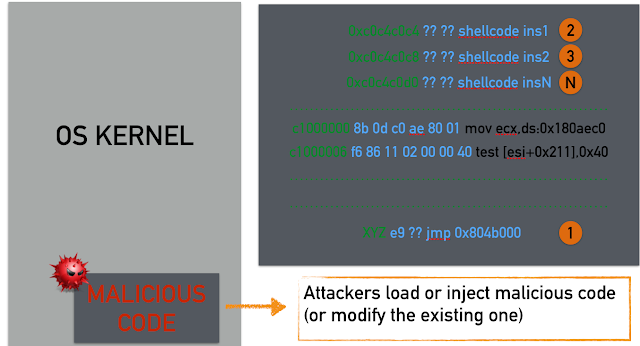

The main difference is that the instructions are not contiguous in memory. ROP is a technique to execute arbitrary code by reusing instructions already present in a program. Each sequence of instructions (a.k.a. gadget) is responsible for fetching the address of the next one (typically from the stack using the ret instruction) and gluing together many small gadgets to perform a predefined computation. In the example depicted above, the memory region under the attacker's control is on the left while the gadgets are the boxes on the right. The numbers close to the boxes represent the execution order of the gadgets, which are not contiguous in memory. Execution of these gadgets requires jumping into different locations of the address space containing executable code (illustrated by the orange arrows). In this way, the data region controlled by the attacker contains only pointers. The end result is that typical exploit mitigations are bypassed.

Given the nature of these attacks, general code-reuse attacks, such as ROP, pose new challenges for analysts.

ROP Analysis Over the years, researchers have completely underestimated the complexity of ROP code and few studies have focused on the discovery of ROP chains in memory. Although, this is a fascinating research area, it is still in its infancy. The fact that there is still more work to be done is illustrated by the main challenges that we identified during the development of ROPMEMU.

Challenge #1: Verbosity The majority of ROP gadgets contain spurious instructions. For example, a gadget intended to increment EAX may also pop a value from the stack before hitting the RET instruction that triggers the next gadget in the chain. Moreover, the code of a ROP chain contains a large percentage of return or other indirect control flow instructions, whose only goal is to connect the gadgets together. These are a few examples of why ROP code is very verbose and contains a large amounts of dead code that makes it harder for analysts to understand it. However, this is probably the simplest problem to solve as many transformations proposed in compiler literature already exist to simplify assembly code.

Challenge #2: Stack-Based Instruction Chaining The most obvious difference between a ROP chain and a normal program is that in a ROP chain, instructions are not consecutive in memory but are instead grouped in small gadgets connected together by indirect control flow instructions. For example, a typical program might contain a single block of 50 instructions that perform a predefined computation while in a ROP chain, these instructions can be split into more than 40 blocks chained together by RET instructions. At first glance, this problem may seem trivial to solve. Since the addresses of each gadget in the chain are saved in memory, one may erroneously think that it would be easy to automatically retrieve them, collect the corresponding pieces of code, and replace the entire chain with a single sequence of instructions. However, stack-based instruction chaining can introduce subtle side effects that are hard to identify through simple static analysis. For instance, since the sequence of gadgets is saved on the stack, but the code of each gadget also interacts with the stack (to retrieve parameters or just because of spurious instructions), in order to correctly identify the address of each gadget it is necessary to emulate every single instruction in the code.

Challenge #3: Lack of Immediate Values Another difference between normal code and ROP chains is the fact that chains are typically constructed with "generic" gadgets (such as "store an arbitrary value in the RAX register") that operate on parameters which are also stored on the stack. As a result, the vast majority of immediate values that are assigned to registers are interleaved on the stack with the gadget addresses. Again, code emulation is required to locate and restore them back to their original position in the code.

Challenge #4: Conditional Branches In a ROP chain, a branch condition implies a change in the stack pointer instead of a more traditional change in the instruction pointer. This means that a simple conditional jump may be encoded with dozens of different instructions spanning multiple gadgets (e.g., to set the flag register according to the required condition, test its value, and conditionally increment the esp register). To translate the chain into more readable code, it is therefore necessary to identify these patterns based on their semantics and replace them with single branch instructions.

Challenge #5: Return to Functions Function calls in ROP are typically implemented as simple returns to the function's entry point. However, since normal gadgets are also often extracted from code located inside libraries, it is hard to distinguish a function call from another gadget. As is the case for statically linked binaries, the lack of information on external library calls can make the reverse engineering process much more tedious and complicated.

Challenge #6: Dynamically Generated Chains The instructions of normal programs are typically located in a read-only section of the executable. In contrast, dynamically modified code is common in malware (e.g., as a result of packing) which severely limits the ability to perform static analysis on malicious code and slows down the reverse engineering process considerably. Since ROP chains are located on the stack instead of read-only memory, it is simple to use gadgets to prepare the execution of other gadgets. This dynamicity means that it is not necessary for the entire chain to reside in memory at the same time. It is instead common to build chains (or parts thereof) on the fly.

Challenge #7: Stop Condition In our research, we assume that the analyst is able to locate the beginning of a ROP chain in memory. However, since an emulator is needed to analyze its content, it is important to also have a termination condition to decide when all the gadgets have been extracted and the emulation process can stop. The fact that complex ROP chains can invoke functions (which in turn may invoke other functions) interleaved with normal gadgets, and the fact that a chain can dynamically generate another chain in a different part of the memory, make this problem very hard to solve in the general case. For example, when does a ROP rootkit (that reuses instructions from the existing code in the kernel) terminate and the normal kernel tasks resume?

The last four challenges have not been discussed publicly because ROP chains have become complex enough to raise these issues in the past two years.

ROPMEMU These challenges in analyzing ROP chains have lead Talos to research better analysis techniques and tools, resulting in the development of ROPMEMU. ROPMEMU is an open source tool available on GitHub that can help analyze code-reuse attacks. Documentation on how to install this tool and how to use all the different plugins and scripts can be found on the Wiki page. Please keep in mind that this is an ongoing research project and should be considered in the alpha stage. If you find any problems, please open an issue so that they can be resolved. If you would like to contribute, please feel free to send us your pull requests.

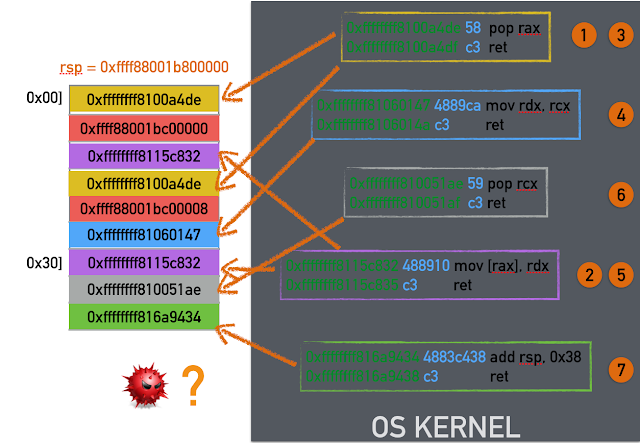

The framework comprises five main analysis phases as depicted in the figure below:

Multipath Emulation This step emulates the assembly instructions that compose the ROP chain. This is the only way to rebuild the exact instance of the running chain at the time of the dump. All possible branches are explored and an independent JSON trace (annotated with the values of registers) is generated for each execution path. By doing this, we can address two challenges: stack-based instruction chaining and dynamically generated chains. This trace contains the CPU context. The framework also keeps track of the memory and has its own shadow stack.

All write operations are intercepted and all the subsequent read operations fetch data from this area. The shadow stack is saved in another JSON file. The emulator is also designed to recognize a number of return-to-library functions, skip over their body, and simulate their execution (addressing the challenge of "return to functions"). It also implements heuristics to detect the chain boundary and stop emulation. Initially, we implemented a small custom emulator that supported the few required x86 and x86_64 instructions and updated the state of the CPU (registers and flags) and memory after each instruction. However, to support the entire instruction set, we adapted our platform to use the recently released Unicorn emulator. The Volatility plugin ropemu implements these concepts and is based on Unicorn and Capstone. It is a proof of concept and has not been extensively tested and suffers from some open Unicorn bugs.

Trace Splitting In this phase, the system analyzes all of the traces generated by the emulator, removes repeated portions, and extracts the unique blocks of code. This part is divided into two steps. In the first, every trace is cut at each branch point, and a new block is generated and saved in a separate JSON trace. During this operation, the framework also records metadata describing the relationships between the different blocks. In the second pass, the chain splitter compares the individual blocks to detect overlapping footer instructions (i.e., gadgets in common at the end of different blocks) and isolates them in separate files. The result of this phase is a set of JSON traces that are the real basic blocks of the chain. This part is implemented in the Python script blocks.

Unchaining In this phase, the system applies a number of assembly transformations to simplify each ROP trace by removing the connections between gadgets and merging the content of consecutive gadgets into a single basic block. This is possible by removing all of the RET, CALL, and unconditional JMP instructions. This step is also responsible for removing immediate values from the stack and assigning them to the corresponding registers (which address challenges in analyzing stack-based instruction chaining and knowing immediate values). This simplifies MOV instructions and transforms POP into MOV instructions. This is possible by fetching the values from the memory. The result of this phase is a binary blob in the target architecture. The Volatility plugin unchain implements this phase.

CFG RecoveryThis pass merges all of the binary blobs generated by the unchain phase into a single program, recovering the original control flow graph of the ROP chain. This phase comprises two steps.

- The traces are merged into a single graph-based representation. The information on how the blocks are connected is specified as an input of the script. This metadata information is generated in the splitting phase.

- The graph is translated into a real x86 program by identifying the instructions associated with the branch conditions and replacing them with more traditional EIP-based conditional jumps (the challenge of analyzing conditional branches). In our case study, a simple conditional jump is implemented by 19 gadgets and 41 instructions. Our framework is able to recognize this condition and generate an equivalent assembly code in the instruction pointer domain. The 19 gadgets are translated into two assembly instructions: a conditional jump (in our case represented by either JZ or JNZ) and an unconditional jump (JMP). These first two steps are implemented in the Python script glue. The CFG recovery component is also in charge of detecting and re-rolling loops. ROP chains can contain both return oriented loops and unrolled loops that are programmatically generated when the chain is constructed. The logic behind the loop rerolling is implemented in the loops script. At the end of this phase, the program is saved in an ELF file (through the dust script), to allow traditional reverse engineering tools (e.g., IDA Pro) to operate on it.

Binary Optimization In the final step, we apply known compiler transformations to further simplify the assembly code in the ELF file. For instance, this phase removes dead instructions in the gadgets and generates a clean and optimized version of the payload (addresses the problem of verbose code). These basic transformations are implemented in the different stages.

For a more detailed analysis, please refer to the original paper.

Evaluation We evaluated ROPMEMU on the most complex ROP-based threat publicly available. Our primary interest in testing ROPMEMU was in the extractions of the chains, the transformations, and the CFG.

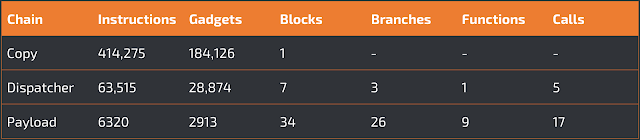

In our first experiment, we tested the ability of the multipath emulator of ROPMEMU to correctly extract the persistent chain (copy chain), and the two dynamically generated chains (dispatcher chain and payload chain). The ROPMEMU emulator was able to automatically retrieve the entire code of all three chains. The copy chain is the longest with 414,275 instructions, but is composed of only a single basic block. The lack of a control flow logic makes this chain similar to a classic ROP payload used in an exploit, with the only difference being that it is composed of over 180K gadgets. This is a consequence of its main task: the creation and copy of the first dynamic component (dispatcher chain) into memory. In contrast, the dispatcher chain and payload chain have a smaller number of gadgets but they have a more complex CFG. In particular, the dispatcher chain contains three branches and seven blocks of code. To recover the entire code, the emulator generated seven distinct JSON traces. Meanwhile, the payload chain was composed of 34 unique blocks and 26 branch points. This means that the CFG had a more complex logic flow. Moreover, this payload chain invokes nine unique kernel functions (find_get_pid, kstrtou16, kfree, __memcpy, printk, strncmp, strrchr, sys_getdents, and sys_read – the last two are hooked by the rootkit) for a total of 17 function calls over the various execution paths.

This experiment proves that ropemu can explore and dump complex ROP chains, which would be impossible to analyze manually. (Note that the current ropemu implementation may have some problems reaching the payload chain due to Unicorn issues.) We believe these chains show the limits of current malware analysis frameworks to cope with return oriented programming payloads.

The results are summarized in the table below:

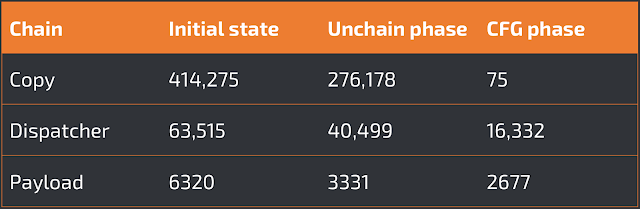

In the second experiment, we show the effect of the other phases of our analysis on the extracted ROP chains. In particular, since it is impossible to show the entire code, we present the effect of the transformations on the payload size. The results are summarized in the table below:

As shown in the third column, the unchain pass reduces the ROP chain size considerably, by 39% on average. The CFG recovery pass filters out the instructions implementing the conditional statements, translates the chain from the stack pointer domain to the instruction pointer domain, and finally applies the loop compression step. These transformations reduce the copy chain from around 414K instructions to only 75 instructions. The payload chain is less affected by these transformations because it contained ROP loops instead of unrolled loop.

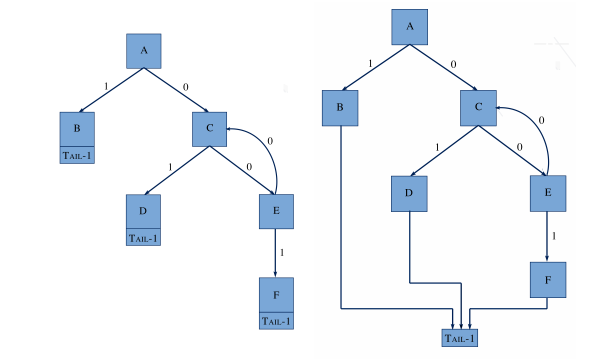

In the third experiment, we tested ROPMEMU's capability to retrieve and recover the control flow graph of a ROP chain. First we show the transformations applied to the control flow graph of the dispatcher chain by connecting all the traces. In this case, the framework adds the sink node.

|

| On the left, the graph illustrates the blocks without any transformation. On the right, the same graph is illustrated with the transformation. We identified and added the "tail" node. |

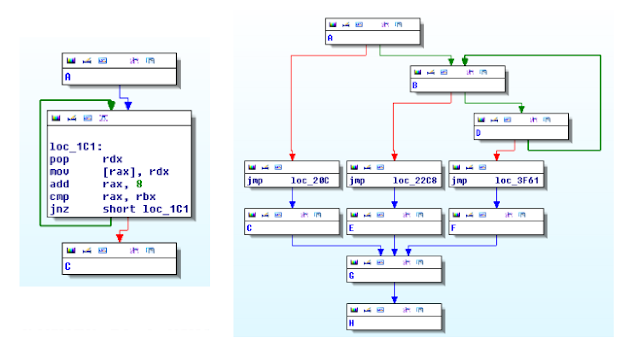

The second step of recovering the CFG works on the binaries blobs and the generated ELF file. This ELF file connects all the blocks by leveraging the metadata information. To test this functionality we opened the resulting file with IDA Pro. In the figure below on the left, we observe the ELF representing the copy chain completely converted into the classic "EIP-based" programming paradigm. The graph is simple, there are no branches and the core functionalities are represented by the main loop highlighted in the picture. In comparison, the figure on the right illustrates the dispatcher chain view in IDA Pro.For the sake of clarity every node is collapsed to generate a smaller picture.

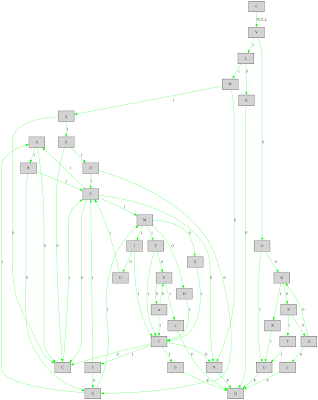

The payload chain has a more complex CFG because it contains the malicious payload logic. Its control flow graph has more than 30 blocks. As we can observe from the next picture, the graph has two main blocks: the sys_read block and the sys_getdents block. In addition, the graph shows also the exit points (Q and C) and the loops (easy to identify from the backward edges). Even if the control flow graph contains few additional edges (due to the spurious optimizations introduced by the loop simplification), the information depicted below provides a quick but detailed overview of the behavior of the payload.

Limitations As with any other binary analysis tool, ROPMEMU has a number of intrinsic limitations. In particular, the proposed solution combines two techniques: memory forensics and emulation. The first requires a physical memory dump acquired after the rootkit has been loaded into memory – and is therefore prone to anti-acquisition techniques. The ROP analysis relies instead on the emulator implementation. The main limitation of an emulation-based solutions is the accuracy of the emulator itself. In particular, this approach is prone to anti-emulation techniques specifically targeting instructions side effects.

The current implementation is in alpha stage and we are aware of the following limitations.

- The current version of the framework fully supports only x86_64 systems and it has not been extensively tested because, to the best of our knowledge, only the ROP rootkit is complex enough to demonstrate the features of ROPMEMU.

- The current version of ropemu, the emulator component on top of Volatility, is based on Unicorn and suffers from some open bugs. The paper has been written with the first and custom version of the emulator. Since then, we decided to rewrite ropemu to leverage the unique features of Unicorn.

Conclusion Code-reuse attacks, and in particular ROP, are widely used to bypass operating system protections and are growing in complexity. Malware authors have started using ROP as a means to hinder analysis and stay under the radar in the never-ending game of cat-and-mouse. ROPMEMU is the first attempt to automate the analysis of complex code implemented entirely using ROP. Thus far, we have tested the framework with the most complex case proposed: a persistent ROP rootkit.

The proposed framework is motivated by the lack of methodologies and tools to analyze in-depth ROP payloads of increasing complexity. While there is still much work to be done, ROPMEMU is a first step and a proof-of-concept from which we hope the entire community can build off of to help analyze these types of attacks. This research illustrates the challenges defenders will face in the future and the potential complexity introduced by these threats.

You can find this tool and associated documentation on TalosIntelligence.com:

http://www.talosintel.com/ropmemu/