Overview

Cisco Talos has been tracking a new version of Smoke Loader — a malicious application that can be used to load other malware — for the past several months following an alert from Cisco Advanced Malware Protection’s (AMP) Exploit Prevention engine. AMP successfully stopped the malware before it was able to infect the host, but further analysis showed some developments in the Smoke Loader sample resulting from this chain of malware that intrigued us. This includes one of the first uses of the PROPagate injection technique in real-world malware. Besides a report released at the end of last week describing a different RIG Exploit Kit-based campaign, we haven’t seen real-world malware using this.

Talos is very familiar with Smoke Loader. For example, it was used as a downloader for a cyberattack that was launched using the official website of Ukraine-based accounting software developer Crystal Finance Millennium (CFM) in January.

Similar to many other campaigns, the initial infection vector was an email with a malicious Microsoft Word document attached. The victims were tricked into opening the attachment and enabling the embedded macros. This started the malware-downloading chain, down to the final Smoke Loader infection and its plugins.

Smoke Loader is primarily used as a downloader to drop and execute additional malware like ransomware or cryptocurrency miners. Actors using Smoke Loader botnets have posted on malware forums attempting to sell third-party payload installs. This sample of Smoke Loader did not transfer any additional executables, suggesting that it may not be as popular as it once was, or it’s only being used for private purposes.

The plugins are all designed to steal sensitive information from the victim, specifically targeting stored credentials or sensitive information transferred over a browser — including Windows and Team Viewer credentials, email logins, and others.

Technical details

Infection Chain

As mentioned above, the infection chain started with an email and an attached malicious Word document (b98abdbdb85655c64617bb6515df23062ec184fe88d2d6a898b998276a906ebc). You can see the content of this email below.

| |||

| Fig. 1 - Phishing Email |

The attached Word document had an embedded macro that initiated the second stage and downloaded the Trickbot malware. (0be63a01e2510d161ba9d11e327a55e82dcb5ea07ca1488096dac3e9d4733d41).

|

| Fig. 2 - Email attachment: IO08784413.doc |

This document downloads and executes the Trickbot malware from hxxp://5[.]149[.]253[.]100/sg3.exe, or hxxp://185[.]117[.]88[.]96/sg3.exe as %TEMP%\[a-zA-Z]{6-9}.exe. These URLs have served up multiple malicious executables in the past, including samples of Trickbot.

In our Trickbot cases, the malware finally downloaded the Smoke Loader trojan (b65806521aa662bff2c655c8a7a3b6c8e598d709e35f3390df880a70c3fded40), which installed five additional Smoke Loader plugins. We are describing these plugins in detail later in the plugins section of this report.

Trickbot (0be63a01e2510d161ba9d11e327a55e82dcb5ea07ca1488096dac3e9d4733d41)

Smoke Loader has often dropped Trickbot as a payload. This sample flips the script, with our telemetry showing this Trickbot sample dropping Smoke Loader. This is likely an example of malware-as-a-service, with botnet operators charging money to install third-party malware on infected computers. We haven’t analysed the Trickbot sample further, but for your reference, we are providing the Trickbot configuration here (IP addresses redacted with bracketed dots for security reasons.):

<mcconf>

<ver>1000167</ver>

<gtag>wrm13</gtag>

<srv>185[.]174[.]173[.]34:443</srv>

<srv>162[.]247[.]155[.]114:443</srv>

<srv>185[.]174[.]173[.]116:443</srv>

<srv>185[.]174[.]173[.]241:443</srv>

<srv>62[.]109[.]26[.]121:443</srv>

<srv>185[.]68[.]93[.]27:443</srv>

<srv>137[.]74[.]151[.]148:443</srv>

<srv>185[.]223[.]95[.]66:443</srv>

<srv>85[.]143[.]221[.]60:443</srv>

<srv>195[.]123[.]216[.]115:443</srv>

<srv>94[.]103[.]82[.]216:443</srv>

<srv>185[.]20[.]187[.]13:443</srv>

<srv>185[.]242[.]179[.]118:443</srv>

<srv>62[.]109[.]26[.]208:443</srv>

<srv>213[.]183[.]51[.]54:443</srv>

<srv>62[.]109[.]24[.]176:443</srv>

<srv>62[.]109[.]27[.]196:443</srv>

<srv>185[.]174[.]174[.]156:443</srv>

<srv>37[.]230[.]112[.]146:443</srv>

<srv>185[.]174[.]174[.]72:443</srv>

</servs>

<autorun>

<module name="systeminfo" ctl="GetSystemInfo"/>

<module name="injectDll"/>

</autorun>

</mcconf>

Smoke Loader packer/injector details

Malware frequently iterates through process lists to find a process to inject. Security researchers know this process well and have created many tools to track the Windows APIs used in this technique, like CreateToolhelp32Snapshot. This Smoke Loader sample avoids iterating through process lists by calling the Windows API GetShellWindow to get a handle to the shell’s desktop window, then calling GetWindowThreadProcessId to get the process ID of Explorer.exe.

Smoke Loader then uses standard injection API to create and write two memory sections in Explorer, one for shellcode and another for a UxSubclassInfo structure to be used later for PROPagate injection.

GetShellWindow -> GetWindowThreadProcessId -> NtOpenProcess -> NtCreateSection -> NtMapViewOfSection x2 -> NtUnmapViewOfSection

The window handle retrieved from the previous call to GetShellWindow has a second purpose. Smoke Loader uses EnumChildWindows to iterate through each of the handle’s child windows to find one containing the property UxSubclassInfo, which indicates it is vulnerable to PROPagate injection.

PROPagate injection was first described by a security researcher in late 2017, though there were no public POCs available when Smoke Loader started using it. The Smoke Loader developers likely used publicly available notes on PROPagate to recreate the technique.

|

| Fig. 3 - PROPagate Injection |

For each child window, the injector calls EnumPropsA to iterate through window properties until it finds UxSubclassInfo. This function also showcases some of the anti-analysis techniques employed by this sample’s packer. There are several unnecessary jumps for control flow obfuscation, including simple opaque predicates leading to junk code.

“Deobf_next_chunk” takes arguments for size and offset for the next chunk of code to deobfuscate and execute, so the bulk of the malicious code is deobfuscated as needed, and can be obfuscated again once the next chunk is loaded. The obfuscation method is a simple one-byte XOR with the same hardcoded value for every piece.

These anti-analysis techniques are accompanied by anti-debugging and anti-VM checks, as well as threads dedicated to scanning for processes and windows belonging to analysis tools. These features complicate forensics, runtime AV scanners, tracing, and debugging.

|

| Fig. 4 - Trigger malicious event handler via WM_NOTIFY and WM_PAINT |

Once the shellcode and UxSubclassInfo data are written to the remote process, the injector calls SetPropA to update the property for the window, then sends WM_NOTIFY and WM_PAINT messages to the target window to force it to trigger the malicious event handler that executes the injected shellcode.

Injected shellcode: Smoke Loader

Smoke Loader received five interesting plugins instead of additional payloads. Each plugin was given its own Explorer.exe process to execute in, and the malware used older techniques to inject each plugin into these processes. Each Explorer.exe process is created with the option CREATE_SUSPENDED, the shellcode is injected, then executed using ResumeThread. This is noisy and leaves six Explorer.exe processes running on the infected machine.

Plugins

As mentioned above, the plugins are all designed to steal sensitive information from the victim, explicitly targeting stored credentials or sensitive information transferred over a browser. Each plugin uses the mutex "opera_shared_counter" to ensure multiple plugins don’t inject code into the same process at the same time.

Plugin 1:

This is the largest plugin with approximately 2,000 functions. It contains a statically linked SQLite library for reading local database files.

- It targets stored info for Firefox, Internet Explorer, Chrome, Opera, QQ Browser, Outlook, and Thunderbird.

- Recursively searches for files named logins.json which it parses for hostname, encryptedUsername, and encryptedPassword.

- vaultcli.dll - Windows Credential Manager

- POP3, SMTP, IMAP Credentials

Plugin 2:

This plugin recursively searches through directories looking for files to parse and exfiltrate.

Outlook

*.pst

*.ost

Thunderbird

*.mab

*.msf

inbox

sent

templates

drafts

archives

The Bat!

*.tbb

*.tbn

*.abd

Plugin 3:

This one injects into browsers to intercept credentials and cookies as they are transferred over HTTP and HTTPS.

- If "fgclearcookies" is set, kills browser processes and deletes cookies.

- iexplore.exe and microsoftedgecp.exe

- HttpSendRequestA

- HttpSendRequestW

- InternetWriteFile

- firefox.exe

- PR_Write in nspr4.dll or nss3.dll

- chrome.exe

- unknown function inside chrome.dll

- opera.exe

- unknown function inside opera_browser.dll or opera.dll

Plugin 4:

This hooks ws2_32!send and ws2_32!WSASend to attempt to steal credentials for ftp, smtp, pop3, and imap

Plugin 5:

This one injects code into TeamViewer.exe to steal credentials

IOC

B98abdbdb85655c64617bb6515df23062ec184fe88d2d6a898b998276a906ebc (IO08784413.doc)

0be63a01e2510d161ba9d11e327a55e82dcb5ea07ca1488096dac3e9d4733d41 (Trickbot)

b65806521aa662bff2c655c8a7a3b6c8e598d709e35f3390df880a70c3fded40 (Smoke Loader)

Mutex: opera_shared_counter

Trickbot IPs:

185[.]174[.]173[.]34

162[.]247[.]155[.]114

185[.]174[.]173[.]116

185[.]174[.]173[.]241

62[.]109[.]26[.]121

185[.]68[.]93[.]27

137[.]74[.]151[.]148

185[.]223[.]95[.]66

85[.]143[.]221[.]60

195[.]123[.]216[.]115

94[.]103[.]82[.]216

185[.]20[.]187[.]13

185[.]242[.]179[.]118

62[.]109[.]26[.]208

213[.]183[.]51[.]54

62[.]109[.]24[.]176

62[.]109[.]27[.]196

185[.]174[.]174[.]156

37[.]230[.]112[.]146

185[.]174[.]174[.]72

Smoke Loader domains:

ukcompany[.]me

ukcompany[.]pw

ukcompany[.]top

Dropped File: %appdata%\Microsoft\Windows\[a-z]{8}\[a-z]{8}.exe

Scheduled Task: Opera scheduled Autoupdate [0-9]{1-10}

Conclusion

We have seen that the trojan and botnet market is constantly undergoing changes. The players are continuously improving their quality and techniques. They modify these techniques on an ongoing basis to enhance their capabilities to bypass security tools. This clearly shows how important it is to make sure all our systems are up to date. Organizations can utilize a multi-layered defensive approach to detect and protect against these kinds of threats. Talos continues to monitor these campaigns as they evolve to ensure that defenses protect our customers. We strongly encourage users and organizations to follow recommended security practices, such as installing security patches as they become available, exercising caution when receiving messages from unknown third parties, and ensuring that a robust offline backup solution is in place. These practices will help reduce the threat of a compromise and should aid in the recovery of any such attack.

Coverage

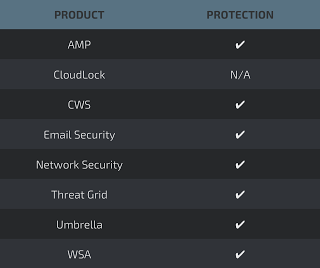

Additional ways our customers can detect and block this threat are listed below.

Advanced Malware Protection (AMP) is ideally suited to prevent the execution of the malware used by these threat actors.

CWS or WSA web scanning prevents access to malicious websites and detects malware used in these attacks.

Email Security can block malicious emails sent by threat actors as part of their campaign.

Network Security appliances such as NGFW, NGIPS, and Meraki MX can detect malicious activity associated with this threat.

AMP Threat Grid helps identify malicious binaries and build protection into all Cisco Security products.

Umbrella, our secure internet gateway (SIG), blocks users from connecting to malicious domains, IPs, and URLs, whether users are on or off the corporate network.

Open Source Snort Subscriber Rule Set customers can stay up to date by downloading the latest rule pack available for purchase on Snort.org.