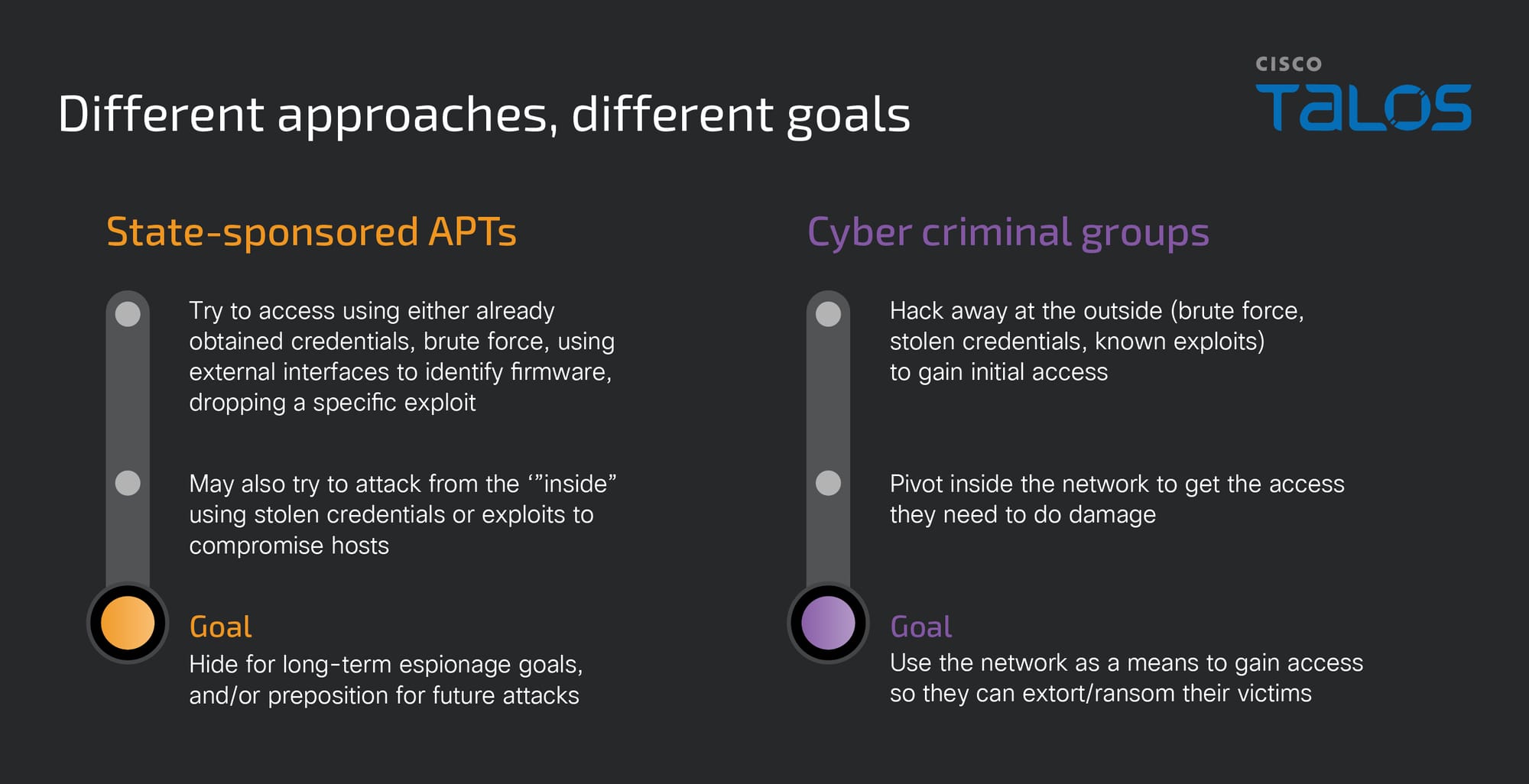

We’ve been discussing networking devices quite a lot recently and how Advanced Persistent Threat actors (APTs) are using highly sophisticated tactics to target aging infrastructure for espionage purposes. Some of these attacks are also likely prepositioning the APTs for future disruptive or destructive attacks.

Talos has also observed several ransomware groups gaining initial access to networking devices to extort their victims. We wrote about these attacks in our 2023 Year in Review report.

The mechanisms and methodology behind these two groups are drastically different, but no less concerning. This is partly because networking devices offer a great deal of access to an attacker. If you can compromise a router, you are highly likely to have a point of ingress into that network.

These attacks are largely being carried out on aging network infrastructure; devices that have long since gone end-of-life, and/or have critical unpatched vulnerabilities sitting on them. Many of these older devices weren’t designed with security in mind. Traditionally, network infrastructure has sat outside of security’s ecosystem, and this makes monitoring network access attempts increasingly difficult.

Adversaries, particularly APTs, are capitalizing on this scenario to conduct hidden post-compromise activities once they have gained initial access to the network. The goal here is to give themselves a greater foothold, conceal their activities, and hunt for data and intelligence that can assist them with their espionage and/or disruptive goals.

Think of it like a burglar breaking into a house via the water pipes. They’re not using “traditional” methods such as breaking down doors or windows (the noisy smash-and-grab approach) — they’re using an unusual route, because no one ever thinks their house will be broken into via the water pipes. Their goal is to remain stealthy on the inside while they take their time to find the most valuable artefacts (credit to my colleague Martin Lee for that analogy).

In this blog, we explore how we got here, and the different approaches of APTs vs ransomware actors. We also discuss three of the most common post-compromise tactics that Talos has observed in our threat telemetry and Cisco Talos Incident Response (Talos IR) engagements. These include modifying the device’s firmware, uploading customized/weaponized firmware, and bypassing security measures.

How we got here

There is a rich history of threat actors targeting network infrastructure — the most notorious example being VPNFilter in 2018. The attack was staged, but potential disaster was averted when the attacker’s command and control (C2) infrastructure was seized by the FBI, preventing the attacker from issuing the final command to take over the devices.

At the time, we spoke about how VPNFilter was the “wakeup call that alerted the cybersecurity community to a new kind of state-sponsored threat — a vast network of compromised devices across the globe that could stow away secrets, hide the origins of attacks and shut down networks.”

The techniques used in VPNFilter gives us plenty of clues as to possible current threat actor motivations. In the attack, the modular design of the malware allowed for many things to take place post compromise – one module even allowed the malware to create a giant Tor network of the 500,000 compromised devices.

A recent attack which may have been inspired by this was the KV Botnet (Lumen released a blog about this in December 2023). The botnet was used to compromise devices including small and home office (SOHO) routers and firewalls and then chain them together, “to form a covert data transfer network supporting various Chinese state-sponsored actors including Volt Typhoon.”

The Beers with Talos team recently spoke about the KV Botnet and Volt Typhoon, a group widely reported by the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA), Microsoft and other organizations to be a PRC-based state actor. They have been known to conduct long-term espionage activities and strategic operations that are potentially positioning them for future destructive/disruptive attacks. Listen to the episode below:

In 2019, we saw another type of modular malware that was designed to target network infrastructure: “Cyclops Blink.” This was dubbed the “Son of VPNFilter” because of the similarities to that campaign.

The Cyclops Blink malware was designed to run on Linux systems, specifically for 32-bit PowerPC architecture. It could be used in a variety of ways, including reconnaissance and espionage activity. It leveraged modules to facilitate various activities such as establishment of C2, file upload/download and data extraction capabilities.

In 2022, Talos wrote about how we had detected compromised MikroTik routers inside of Ukraine being leveraged to conduct brute force attacks on devices protected by multi-factor authentication. This continued the pattern we have seen since our investigation into VPNFilter involving actors using MikroTik routers.

For more insights into the status of attacks on network infrastructure, here is Talos’ Matt Olney and Nick Biasini talking about what Talos has observed over the past 18 months:

Post compromise tactics and techniques

Compromising the network for persistent access and intelligence capture is a multi-step process and requires a lot of work and expertise in targeted technologies which is why we typically only see the most sophisticated threat actors carry out these attacks.

Below are some techniques that Talos has observed post compromise on out-of-date networking equipment, in order to maintain persistent access. We initially discussed these in our threat advisory in April, as well as our 2023 Year in Review, but due to the sophisticated nature of these attacks and the continued exploitation, we wanted to dive deeper into some of these tactics:

1) Modifying the firmware

Talos has observed APTs modifying network device firmware on older devices to add certain pieces of functionality, which will allow them to gain a greater foothold on the network. This could be adding implants or modifying the way the device captures information.

An example of this is the recent exploitation of Cisco IOS XE Software Web Management User Interface. One attack included the deployment of an implant we called “BadCandy” which consisted of a configuration file (“cisco_service.conf”). The configuration file defined the new web server endpoint (URI path) used to interact with the implant. That endpoint receives certain parameters that allowed the actor to execute arbitrary commands at the system or IOS level.

Another example is from September 2023, when CISA wrote about how BlackTech was observed modifying firmware to allow the installation of a modified bootloader which helps it to bypass certain security features (while creating a backdoor to the device).

Detecting the modification of firmware is extremely difficult for defenders. Occasionally, there may be something in the logs to imply an upgrade and reboot, but turning off logging is usually one of the first steps attackers take once they are inside a network.

This again highlights the need for organizations to sunset aging network infrastructure that isn’t secure by design, or, at the very least, increasing cybersecurity due diligence on older equipment such as configuration management. Performing configuration comparisons on firmware may help to highlight when it has been altered by an adversary.

2) Uploading customized/weaponized firmware

If threat actors cannot modify the existing firmware, or they need additional levels of access that they don’t currently have, adversaries can upload customized or old firmware they know have working exploits against it (in effect, reverting to an older version of the firmware).

Once the weaponized firmware has been uploaded, they reboot the device, and then exploit the vulnerability that is now unpatched. This now provides the threat actor with a box that can be modified with additional functionality, to exfiltrate data, for example.

Again, as with the modification of firmware tactic, it’s important to check your network environment for unauthorized changes. These types of devices need to be watched very closely, as threat actors will want to try and prevent system administrators from seeing the activity by turning off logging. If you’re looking at your logs and it looks like someone has actually turned off logging, that is a huge red flag that your network has been infiltrated and potentially compromised.

3) Bypassing or removing security measures

Talos has also seen threat actors take measures to remove anything blocking their access to fulfil their goals. If for example they want to exfiltrate data, but there’s an access control list (ACL) that blocks the actor from being able to access the host, they may modify the ACL or remove it from the interface. Or they may install operating software that knows to not apply ACLs against certain actor IP addresses, regardless of the configuration.

Other security measures that APTs will attempt to subvert include disabling remote logging, adding user accounts with escalated privileges, and reconfiguring SNMP community strings. SNMP is often overlooked, so we recommend having good, complex community strings and upgrading to SNMPv3 where possible. Ensure that your management of SNMP is only permitted to be done from the inside and not from the outside.

The BadCandy campaign is a good example of how an actor can remove certain security measures. The adversary was able to create miniature servers (virtualized computers) inside of compromised systems which created a base of operations for them. This allowed the threat actors to intercept and redirect traffic, as well as add and disable user accounts. This meant that even if the organization were to reboot the device and erase the active memory, the adversary would still have persistent accounts – effectively a consistent back door.

Additional campaign objectives

In our original threat advisory, we also posted a non-exhaustive list of the type of activities Talos has observed threat actors take on network infrastructure devices. The point behind this is that threat actors are taking the type of steps that someone who wants to understand (and control) your environment.

Examples we have observed include threat actors performing a “show config,” “show interface,” “show route,” “show arp table” and a “show CDP neighbor.” All these actions give the attackers a picture of a router’s perspective of the network, and an understanding of what foothold they have. Other campaign objectives include:

- Creation of hub-and-spoke VPNs designed to allow the siphoning of targeted traffic from network segments of interest through the VPN.

- The capture of network traffic for future retrieval, frequently limited to specific IPs or protocols.

- The use of infrastructure devices to deliver attacks or maintain C2 in various campaigns.

Read more about campaign objectives

Recommendations

The first thing to say when it comes to recommendations is that if you are using network infrastructure that is end of life, out of support, and now has vulnerabilities that cannot be patched, now really is the time to replace those devices.

To combat the threat of aging network infrastructure as a target, Cisco became a founding member of the Network Resilience Coalition. Along with other vendors in this space and key governmental partners, the group is focussed on threat research and recommendations for defenders. The initial report from the Network Resilience Coalition was published at the end of January 2024 and contains a broad set of recommendations for both consumers of networking devices and product vendors.

Earlier this month, Cisco’s Head of Trust Office Matt Fussa wrote about how organizations should view these recommendations, and the overall threat that end-of-life network infrastructure poses on a national security level.

The report from the Network Resilience Coalition contains an in depth set of recommendations for network infrastructure defense. Here is a brief summary:

Key recommendations from the report for network product vendors include:

- Align software development practices with the NIST Secure Software Development Framework (SSDF).

- Provide clear and concise details on product “end-of-life,” including specific date ranges and details on what support levels to expect for each.

- Separate critical security fixes for customers and not bundle those patches with new product features or functionality changes.

- Get involved in the OpenEoX effort in OASIS, a cross-industry effort to standardize how end-of-life information is communicated and provide it in a machine-readable format.

Purchasers of network products should:

- Favor vendors that are aligned with the SSDF, provide you with clear end-of-life information, and provide you with separate critical security fixes.

- Increase cybersecurity diligence (vulnerability scanning, configuration management) on older products that are outside of their support period.

- Periodically ensure that product configuration is aligned with vendor recommendations, with increasing frequency as products age, and ensure implementation of timely updates and patches.

As the report says, “These recommendations, if broadly implemented, would lead to a more secure and resilient global network infrastructure and help better protect the critical infrastructure that people rely on for their livelihood and well-being.”

From a Talos perspective, we are keen to re-emphasize this point and help our customers transition from equipment that has become end-of-life. Using networking equipment that has been built with secure-by-design principles such as running secure boot, alongside having a robust configuration and patch management approach, is key to combatting these types of threats. Ensure that these devices are being watched very carefully for any configuration changes and patch them promptly whenever new vulnerabilities are discovered.

Proactive threat hunting is also one of the ways that organizations can root out visibility gaps and hints of incursion. Look for things like VPN tunnels, or persistent connections that you don't recognise. This is the type of thing that will be left in an attack of this nature.

And finally, the definition of post compromise means that the attacker had gained some form of credentials to get them to the place where they could then launch the exploit and get deeper access to the device.

Our recommendations are to select complex passwords and community strings, use SNMPv3 or subsequent versions, utilize MFA where possible, and require encryption when configuring and monitoring devices. Finally, we recommend locking down and aggressively monitoring credential systems like TACACS+ and any jump hosts.

Additional resources

State-sponsored campaigns target global network infrastructure (Talos blog)

Network Resilience: Accelerating Efforts to Protect Critical Infrastructure (Cisco blog)

Network Resilience Coalition: Full report

Securing Network Infrastructure Devices (CISA)