By Jaeson Schultz.

Dumpster diving — searching through the trash looking for items of value — has long been a staple of hacking culture. In the 1995 movie "Hackers," Acid Burn and Crash Override are seen dumpster diving for information they can use to help them "hack the Gibson." Of course, not all trash is physical garbage located in a dumpster behind an office building. Some trash is virtual. Just like real physical clues that can be found inside a dumpster, some pieces of digital garbage are no less useful/valuable/interesting. But what sorts of digital artifacts do people discard and what are the implications of this information falling into the "wrong" hands?

I spend a lot of time proactively looking for sources of malicious email, and brainstorming new ways to find more of it. By finding more malicious emails, Cisco Talos can better tune our products to protect against the latest email attacks.

Typically, when it comes to finding new sources of malicious mail, it is often easiest to look for locations where illegitimate messages are already flowing and tap into those places. Some of the best sources of email garbage are inside domain names that once existed but have since expired. It is helpful if these domains formerly belonged to organizations having significant exposure on the internet (e.g. sending email, providing digital services, hosting content, etc.). While expired domain names can make excellent sources of email attack data, occasionally, these old domain names still receive legitimate traffic. And so, on our never-ending quest for the virtual "trash" of the internet, we sometimes find interesting "treasure." Or as the old adage goes, "one man's trash is another man's treasure."

Bank error in your favor

Expired domains once belonging to financial service providers are interesting because they can be a magnet for malicious traffic. While out domain dumpster diving, Talos ran across a domain name that once belonged to a bank in Massachusetts, "chartbank.net". According to our research, the bank had been sold, and afterward, the original bank domain name was left to expire.

This bank domain can be found among old lists of financial institutions, email addresses from the domain still exist in users' contact databases, and messages from users at the bank's domain can still be found in email archives. Since the domain is part of the financial industry, it's often targeted by attackers who are looking to compromise financial data and networks. However, these types of domains can also receive very interesting traffic from legitimate sources.

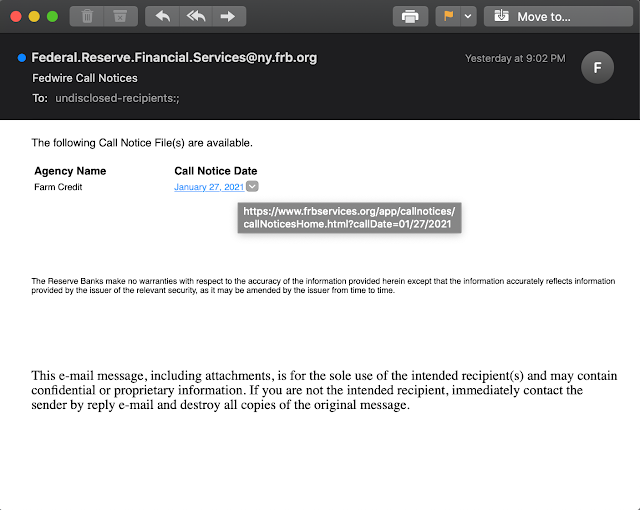

For example, here is an email from a Federal Reserve Bank mailing list.

An email from the Federal Reserve Bank intended for other banks.

The domain also still receives email from users and organizations that were contacts of employees at the bank.

A personal email intended for one of the employees of the bank.

An undead ad network

Some domains continue to receive a decent amount of internet traffic even though the registration on the domain has long expired. During one of our domain dumpster diving sessions, we ran across a domain name, "u-ad.info", that was formerly used to serve ads for an ad network named UAds. In fact, as recently as September 2020, the UAds webpage still displayed the following text:

"For you who have website(s) and want to monetize easily, you can register your websites to u-ad.info for FREE. Create your ads space in your own website, attach our scripts, and you are completely done. The ads will be randomatically [sic] shown in your websites according [to] your website profile, website audience, and website ranking. Whenever a visitor clicks or sees the ads, you will receive your U-Ad points that you can redeem [at] any time."

When we searched for traces of this domain, it became apparent that an entire ISP was rewriting its users' web traffic to inject ads from this ad network. Talos re-registered this domain, and we put up a web server to record the requests we received. In under two weeks, we received more than 1.1 million requests for ads from 236,776 unique IP addresses.

An HTTP access log showing examples of requests we received for ads.

Attackers typically work very hard to get malicious code into web pages in the first place, so if this domain had fallen into the wrong hands, someone with bad intentions could have carried out significant attacks.

Keyboard SMASH!

Some people will just make up any data to fill a form field online, and if you aren't feeling especially creative, the good ol' keyboard smash technique can yield a bunch of characters very quickly. Having many adjacent characters on a keyboard can be a giveaway that the user has chosen the "keyboard smash" technique. Occasionally, people will do this when testing out new features of a website, or when signing up for a site where the user does not want to reveal their true identity.

Talos registered an unregistered keysmash domain that we had seen having a decent volume of DNS traffic: adasdad.com. When we turned on the email for this domain, some of the contents amazed us.

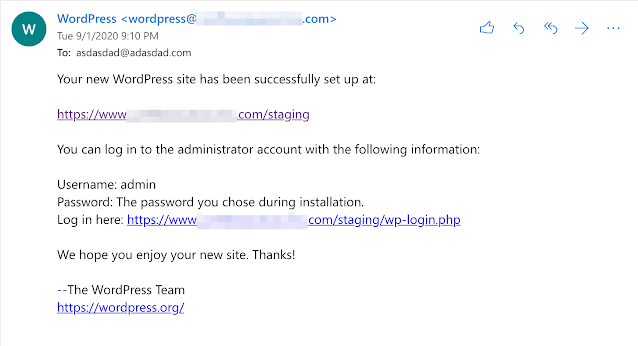

One email message we received was related to a new WordPress site that was set up for a restaurant. Whoever installed this WordPress site chose the email address "asdasdad@adasdad.com" as the administrator. Because of this, we could have reset the password and logged in. (We didn't.)

An email from WordPress informing us we are admins on someone's site.

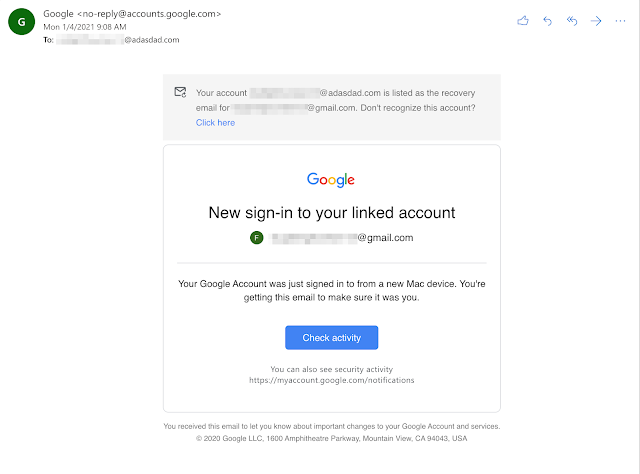

Next, we encountered a user that made up a "fake" address at the adasdad.com domain as their Google account recovery email. Every time they sign into their Google account, an email like the following is generated and sent to our keysmash domain.

This user designated an address at our domain as their account recovery email.

A user with a Facebook business page was apparently experimenting with some of Facebook's features, and sent an invitation to manage their business page to "adsadada@adasdad.com" — no doubt an address they believed would never exist.

An email informing us we have administrative access to someone's Facebook business page.

Users even used made up email addresses at the adasdad.com domain to sign up for services such as Netflix. The email below was from a live Netflix subscription which was registered using the email address "akdhahdasdad@adasdad.com".

An email sent to our domain for an active Netflix account.

Diving into the mining pool

Another interesting type of website that you sometimes run across when domain dumpster diving are domain names formerly used by cryptocurrency miners. Cryptocurrency mining can be performed solo, however, when cryptominers combine their resources, they can increase their productivity and receive more regular earnings. To combine mining resources, miners form mining "pools" which organize multiple mining clients into a single monolithic entity. Occasionally, domains used by these mining pools go away, but not everyone gets the memo, and some zombie mining clients will continue to inquire at the mining pool domain whether there is any mining work to be performed.

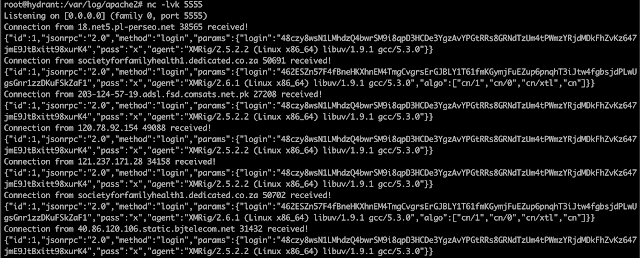

While out domain dumpster diving, Talos ran across a former Monero mining pool domain, "minexmr1.com". After re-registering this domain, we noticed we were receiving traffic on some of the most common cryptomining ports (e.g. 3333 and 5555). We listened to these ports and saw that the mining clients were running xmrig software and seeking Monero mining jobs.

Netcat shows connections from miners looking for Monero mining jobs.

It would be trivial to replace the mining pool server that would normally have organized this mining pool at this domain with a cryptomining proxy such as xmrig-proxy. Proxies such as "xmrig-proxy" are used by individual cryptominers to harness multiple mining resources so that they can focus these resources toward a single upstream mining pool or move the resources to a new mining pool in unison without needing to re-do the configuration across multiple devices. Using a mining proxy in this manner would allow the owner of this domain to take advantage of these zombie mining clients, connect them to an upstream mining pool, and thus earn a passive income without paying anything to downstream miners.

Victims up for grabs

After a computer attack is disrupted, we would like to imagine that the perpetrators are apprehended, victims are all notified, the crime scene is cleaned up, and the world is made safe once again until the next attack. The reality is, of course, much messier. Most malicious actors are never caught. Victims aren't always notified, and when they are, they can often be incredulous or indifferent about the attack. Security professionals sometimes help clean the "crime scene" by sinkholing command and control (C2) domains or DGA domains used by attackers to accomplish their misdeeds. However, many times everyone just walks away after an attack is disrupted, and the attackers' domain names are left fallow, ready to be scooped up by…anybody.

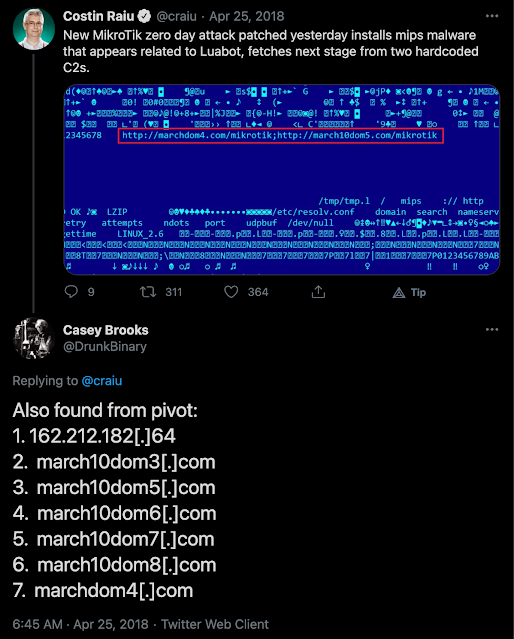

For example, back in 2018, there was a zero-day attack involving Mikrotik routers. The attack was disrupted after the vendor released a patch. Eventually, the attacker domains involved fell out of registration.

Tweet regarding a zero-day attack that occurred in 2018 involving several attacker-controlled domains.

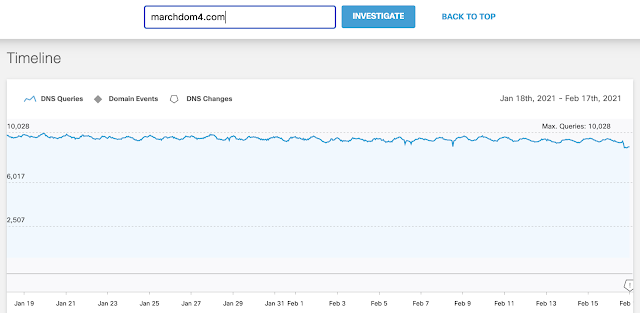

It turns out that several of the victims from this attack who had their Mikrotik routers compromised either didn't get the memo about the attack, or just didn't care to fix the problem. As a result, their routers continued reaching out into the void. For example, viewing the timeline for the attacker C2 domain "marchdom4.com" in Umbrella Investigate, we see there is a substantial amount of traffic indicating several machines that are still attempting to communicate with the attackers.

Umbrella query volume for the attacker C2 domain marchdom4.com.

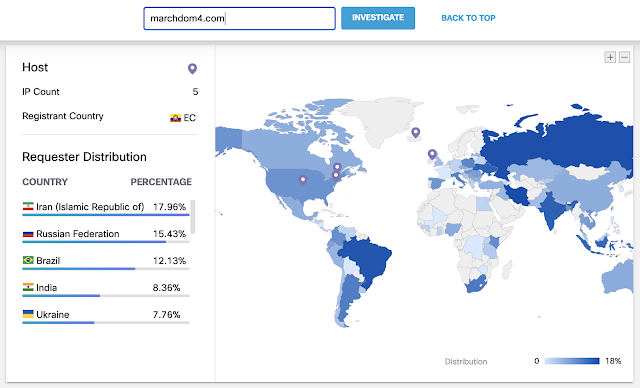

When we check the distribution of the requests received by Umbrella, the traffic is distributed pretty evenly worldwide.

Umbrella shows the distribution of DNS requests for the attacker C2 domain marchdom4.com.

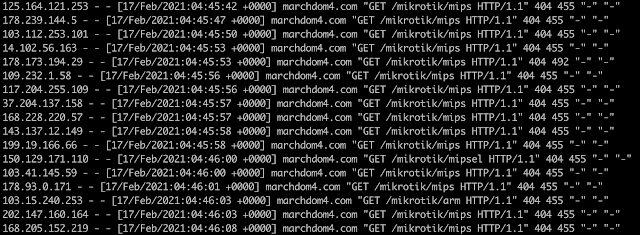

Talos re-registered this domain name and analyzed the traffic that we received. We found thousands of victims who were compromised in the original attack nearly three years ago that were still reaching out in vain searching for the next stage payload of the attack.

An HTTP access log showing requests from victims for the next stage of the malware payload.

If this domain fell into the hands of a threat actor, they could potentially claim these victims from the previous attack as their own, perhaps even "framing" the original attackers for new malicious activity in the process.

Conclusion

The domains we've discussed here really are just the tip of the iceberg. More domains are expiring daily, and the influx of new top-level domains has also enriched the landscape for expired-domain speculators. Having the proper tools to look for these domains, one can find domains that still receive, for whatever reason, a substantial amount of network traffic. When we look at these traffic streams we often see ghosts from the past.

Personally, after being online for over 30 years, I have lost track of the number of different sites I have "signed up" to receive some service or another. Think about the domain names where you have a presence. How do you use these various domain names? If they were to go away for some reason, would there be any sensitive data left over for others to recover or find? Imagine a worst-case scenario: An attacker re-registers these domain names and steals information, or uses the information they find to conduct additional attacks.

These attacks could be completely passive, just setting up a domain and collecting the information that flows in, panning for gold. Or they could take the form of simple social engineering attacks, such as impersonating a legitimate organization in phishing or other scams. Alternatively, domains from URLs embedded in web content that are meant to load something innocuous could potentially turn "bad" if the domain is left unregistered. How would your computer and network defenses fare against an attack like this? In any case, traffic from your network which is headed to internet "dead ends" should be investigated to avoid becoming a victim should those "dead ends" suddenly give way to shady internet neighborhoods.

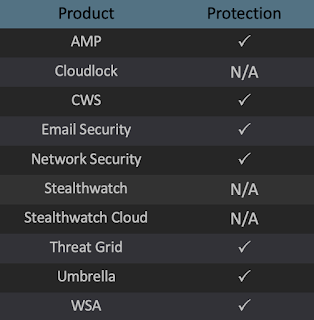

Coverage Additional ways our customers can detect and block threats such as these are listed below.

Advanced Malware Protection (AMP) is ideally suited to prevent the execution of malware used by threat actors at questionable domains.

Cisco Cloud Web Security (CWS) or Web Security Appliance (WSA) web scanning prevents access to malicious websites and domains, and detects malware.

Email Security can block malicious emails sent by threat actors as part of phishing or other social engineering campaigns.

Network Security appliances such as Next-Generation Firewall (NGFW), Next-Generation Intrusion Prevention System (NGIPS), andMeraki MX can detect malicious activity associated with questionable domains.

AMP Threat Grid helps identify malicious binaries and build protection into all Cisco Security products.

Umbrella, our secure internet gateway (SIG), blocks users from connecting to malicious domains, IPs, and URLs, whether users are on or off the corporate network.

Open Source Snort Subscriber Rule Set customers can stay up to date by downloading the latest rule pack available for purchase on Snort.org.