Editor’s note: This post is the first in a new series from Talos looking at high-level topics across the cybersecurity space. Our researchers rely on years of expertise, data, and tremendous visibility; applying what we can learn from history, research, and analysis to nascent security challenges. Please lookout for more “On the Radar” posts in the future.

The cyber world today is chaotic, as the continual escalation in malicious activities from state-sponsored actors and criminal organizations has made being a defender an increasingly difficult task. Complicating matters is the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic, now entering its third year, that is completely shifting the ways we work. But we're defenders, so we're used to impossible odds and long hours of fighting the good fight, it's time we leverage the work shift to even the playing field a bit.

The pandemic and associated hybrid work shift haven't just introduced new challenges they've exacerbated the problems we already face. For example, the stressed-out worker that falls for the COVID-19 themed lure that leads to a ransomware attack. The development teams that are tasked with remediating vulnerabilities that lose access to key tools and resources when working remotely. Even the employee at a software vendor that doesn't have adequate security protections when outside the office, facilitates a compromise that results in a supply chain attack. These are just a few of the countless scenarios that organizations are now facing. The shift to a permanent hybrid work environment is going to require new architectures to be built and existing architectures to be overhauled — providing an opportunity to secure it for the threats we face. The supply chain is being attacked by groups that are both state-backed and financially motivated, both known and unknown vulnerabilities continue to affect the industry, and state-sponsored actors continue to escalate while criminal cartels have taken over the multi-billion dollar crimeware industry. In short, it looks a little bleak.

Some of the enduring challenges and threats we face require government action, both domestically and multilaterally in cooperation with global partners. In the U.S., President Joe Biden's administration is pursuing a whole-of-government approach to countering the ransomware threat, which has included conducting law enforcement operations against major ransomware groups like REvil, NetWalker and DarkSide, and the adoption of new policies aimed at deterring companies from paying ransomware operators and holding government contractors responsible if they fail to report a data breach. On the international front, more than 30 countries held the first global ransomware summit in October, Russian authorities recently arrested numerous members of the REvil ransomware gang, and global partners disrupted the notorious Emotet botnet in 2021, temporarily stopping its operations.

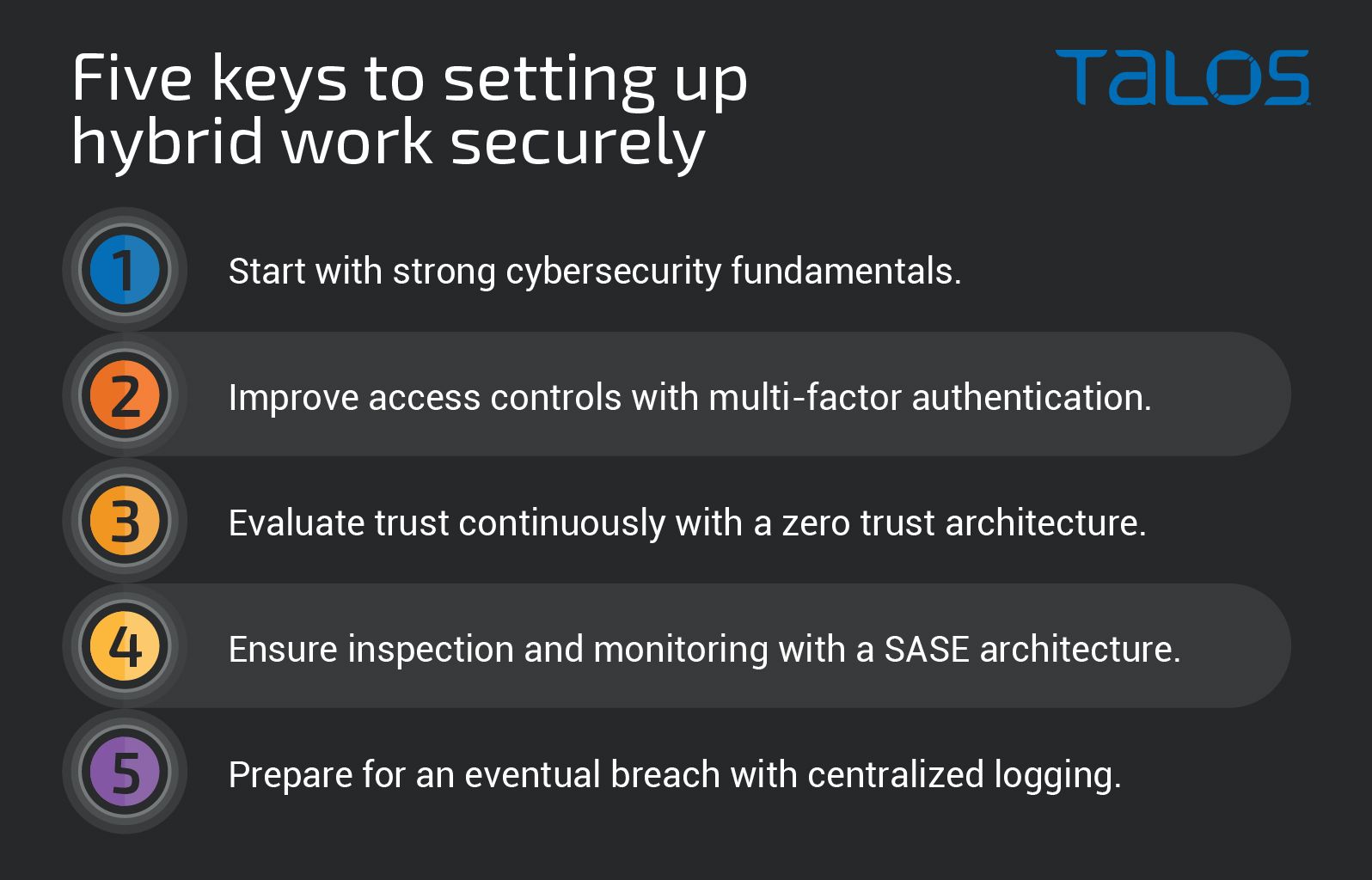

Despite these positive efforts, we recognize that such significant initiatives take time to execute and their benefits may be short-lived or quickly superseded by the next threat, as adversaries are always discovering new ways to stay ahead. To that end, there are things that organizations and network defenders can do from a policy and technology standpoint to increase security and accelerate change. Based on our observations from Cisco Talos Incident Response (CTIR) engagements and threat research, integrating multi-factor authentication (MFA), implementing a zero-trust framework, and building a Secure Access Secure Edge (SASE) architecture are essential policies for organizations to adopt in order to better secure hybrid work environments. These concepts alone are insufficient and need to be combined with strong security fundamentals.

Supply chain attacks are on the rise

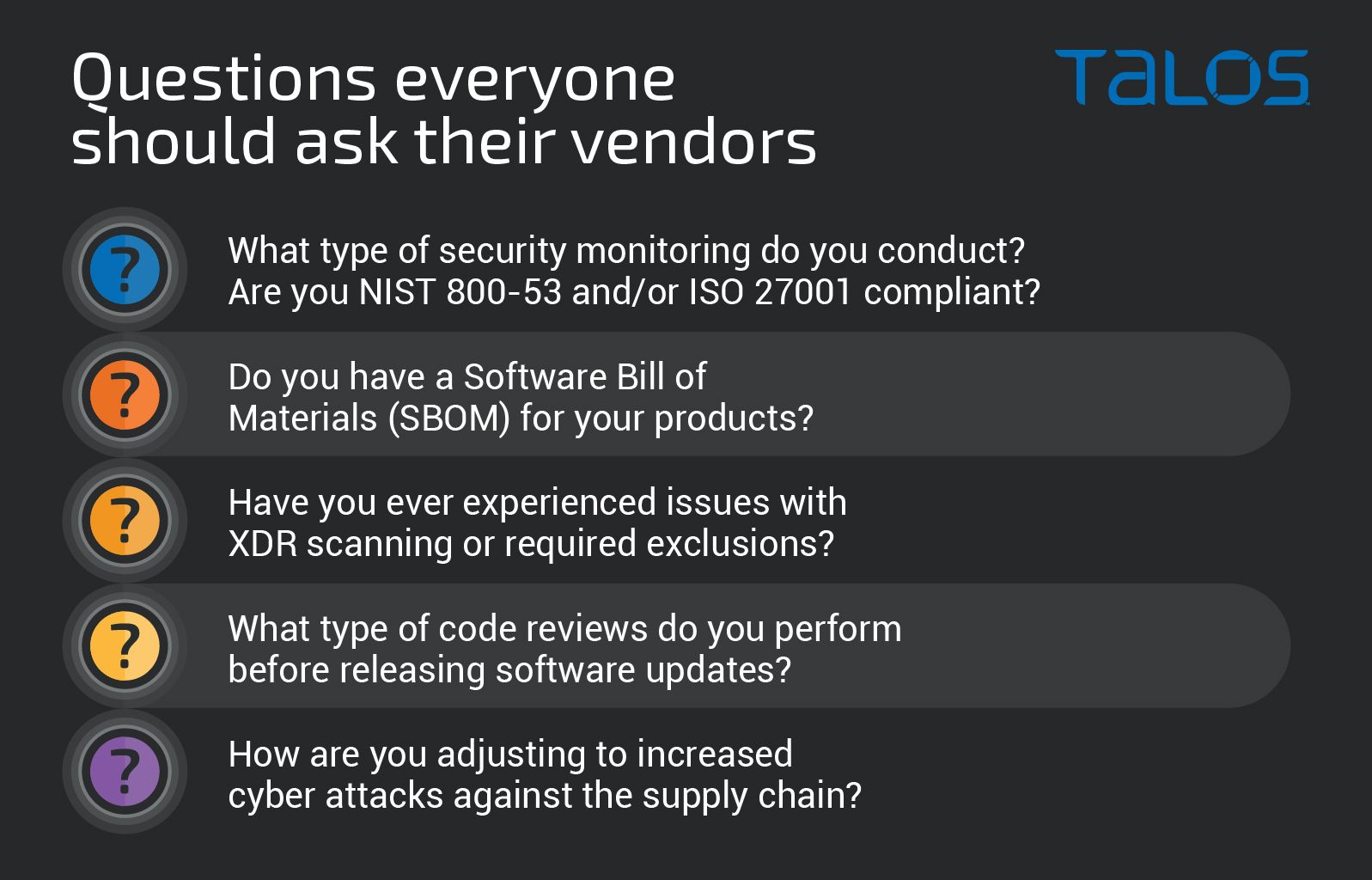

The increasing frequency of supply chain attacks highlights the need for organizations to re-evaluate access, hold vendors to higher standards, and look to implement zero-trust frameworks to mitigate this increasing attack surface.

The escalation has been evident over the past several years, beginning with NotPetya in 2017, which brought the software supply chain into focus. Since then, software has remained a common target of threat actors — including attacks that compromised administrative tools such as CCleaner and SolarWinds — due to the access they provide adversaries to such a high volume of unsuspecting victims. The users, level of access, and the potential for scanning exclusion make these types of software ideal targets. As prominent security organizations continue to improve their defenses, attacking through the supply chain is increasingly becoming the path of least resistance.

There are two common misconceptions we see in this space today: The first is that these types of attacks are only carried out by state-sponsored actors. Historically, this may have been true, but the Kaseya compromise, which was attributed to REvil ransomware operators, indicates cybercrime gangs are also attempting to exploit this threat space. There have also been a variety of software-focused supply chain attacks with criminal intent, especially in open-source package managers like NPM, GitHub and YARN, along with browser extensions. The software supply chain is far from the exclusive playground for nation states.

There's also the misconception that the supply chain threat only affects software and requires more sophisticated capabilities associated with interdiction. But we see plenty of services that are targeted, too. Our discovery of the Sea Turtle activity is a great example. This attack wasn't only a service-based supply chain attack, but was targeted against one for the fundamentals of the internet: DNS. While there are many other types of supply chain attacks, those affecting software and services are those we see most often in the wild.

These types of attacks require planning and development, as was evidenced through the techniques leveraged in the Solarwinds incident. The aggressors constructed packets to mimic SolarWinds' packet construction, making detection difficult. Before the service-based Kaseya attack, adversaries leveraged multiple zero-days to compromise the network, suggesting they likely had conducted ample reconnaissance prior to the operation to identify vulnerable entry points. This could include the development or purchase of zero-day vulnerabilities against the target.

As a response to this increased targeting and activity, organizations need to move away from the blind trust paradigm imposed by vendors and move into a more "trust but verify" model. It may not be possible to completely remove the risk of supply chain attacks, but organizations don't need to accept every requirement from a vendor without questioning it or monitoring it.

It is important to recognize that vendors may not have the same security posture and requirements as one's own organization, and as security leaders, it's our job to acknowledge this possibility and take the necessary measures to prevent security gaps. Monitoring, network-level segregation and user-level segregation can provide a solid base to defend against these threats. This should also be complemented by a zero-trust architecture, making it more difficult for attackers to move laterally.

One final point here is around setting up exclusions for extended detection and response (XDR). It is common in product documentation to request for the software to be put into an exclusion group to ensure it isn't accidentally detected by a security solution. This has been shown to be a huge liability if the excluded software is, in fact, compromised. Organizations need to be wary of solutions that require this type of exclusion, as it creates a blind spot on many networks, which could be devastating in the event of a supply chain attack. The SolarWinds incident is a stark reminder of what happens if a solution with high levels of access throughout the network is compromised — it's going to be exacerbated if XDR isn't scanning it.

Vulnerabilities, regardless of patch status, shake up the landscape

In response to the recent spate of severe vulnerabilities, including those affecting Log4j and Microsoft Exchange servers, and their cascading effects, organizations should look for a software bill of materials, or "SBOM," from vendors when considering software options. That should allow a quick determination of how vulnerabilities in specific libraries or open-source software could change daily operations and hopefully allow for a more thorough and thoughtful response. In 2020, we had the Hafnium vulnerabilities in Microsoft Exchange Server that were initially leveraged by state-sponsored actors and then turned loose on the larger internet, and Log4j, which may end up being one of the most widely distributed vulnerabilities we've ever seen.

Generally, this landscape can be broken into two broad categories. First, there are disclosed vulnerabilities in libraries and software that are heavily used by both organizations and vendors. Second, are the staggering amount of zero-days we saw exploited in targeted attacks in 2021. One notable aspect to the zero-day usage is how much of it has been associated with the compromise of dissidents and activists in countries around the world, with a focus on mobile platforms. Then there is Hafnium, which started as a targeted zero day and then was unleashed on the larger internet, causing significant disruptions and resulting in a spike in Cisco Talos IR engagements.

In 2021, we saw more than 50 instances of in-the-wild exploitation of zero-day vulnerabilities. We saw more zero-days exploited in the wild in 2021 than we did in all of 2020 and 2019 combined. Additionally, at the recent Tianfu Cup hacking contest in China, there were no less than 30 successful exploits demonstrated against the shortlist of targets, including a handful that affected the latest versions of Windows and iOS, all of which were likely reported to the Chinese government due to recent regulation changes. The most recent example of this is Alibaba being penalized by the Chinese government for not disclosing Log4j to them in advance.

This activity, albeit not new, has had a subtle impact on the threat landscape and is increasing the attention on behavioral-based detection. Behavioral-based detection has always been a trade-off between catching malicious activity and casting a wide enough net that may increase false positives. These types of rules will always generate false positives, as sometimes legitimate users conduct activities that appear malicious. On the flip-side, however, it may catch some red teaming activities or a ransomware cartel that is just starting to poke around the network. For instance, the mechanisms these cartels use led to our creation of internal playbooks outlining their tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) that help us identify and stop the behavior prior to ransomware deployment.

The extraordinarily high payouts the ransomware cartels have received will also allow them to increase sophistication. As we saw with Kaseya, these cartels have the ability to purchase or develop zero-days to be leveraged in attacks, a trend that should concern us all and another reason why behavioral protection will continue to be an important aspect of detection in 2022 and beyond.

How we can architect additional protections, starting with MFA

Organizations need to plan for the landscape they are going to have to protect. That means focusing on things like MFA, security fundamentals, and implementing zero-trust frameworks whenever possible. Not only has the landscape changed, but the way people work has also changed. Moving to a SASE architecture is going to prepare organizations as this shift continues.

This security approach has to be resilient against infrastructure attacks like Sea Turtle, and needs to detect and block the barrage of weaponized exploits and supply chain attacks coming from state-sponsored actors and criminals. It also must maintain the security of the network while well-funded criminal organizations are conducting unauthorized red team exercises around the globe. Needless to say, it's a daunting task.

One advantage we have is the wisdom that comes from those that have already been breached and their lessons learned. This includes our observations from the countless engagements our incident response teams have been involved in over the years. From those incidents, we commonly discover that the attack could have been mitigated simply if MFA had been enabled. MFA can significantly reduce the ability of actors to gain initial access or the impact of escalating privileges by requiring users to provide two or more verification factors to gain access to a resource. Cisco Talos Incident Response (CTIR) frequently observes ransomware incidents and other attacks that could have been prevented if MFA had been enabled on critical services.

Throughout 2020 and 2021 we saw nation-states concerned with bypassing things like MFA, targeting SAML tokens in high-profile incidents. These incidents show the value MFA has and how authentication plays a strong role in thwarting malicious behavior. Whether it's a nation-state launching an espionage attack or a ransomware cartel affiliate establishing a foothold for further compromise, the access required to inflict real damage can be limited with MFA.

It's impossible to implement MFA everywhere, but the goal is to increase the monitoring around those exceptions so any abuse can be identified quickly and stopped. A real-life use case is the SeaTurtle attack. MFA would have prevented the attackers from achieving their objectives even after directing the DNS and harvesting their victims' credentials. Additionally, it likely would have stopped them from making the changes to the DNS records themselves.

Security fundamentals can be the difference in an incident

Installing the latest piece of security technology can greatly improve the security of an organization, but there is no replacing the fundamentals required to successfully secure an enterprise. An accurate asset list, current documentation and policies — especially those related to patching — are fundamental when it comes to an incident. The last thing you want is to be in the middle of an active incident to find out you don't have an accurate inventory of assets or that you haven't patched anything in six months. Ensuring fundamentals like network segmentation and proper access controls are implemented will limit the effects of a breach.

Organizations should always plan based on the idea they will be breached at some point and need a cybersecurity incident response plan that includes all the stakeholders in the process. During an incident, it is crucial that the appropriate departments can make decisions and take actions so that the containment can happen as soon as possible, as every minute counts. Preparing and practicing your processes related to an incident can make the difference between mitigating a compromised system and suffering a total breach.

Another key finding is related to logging. Logging can be difficult and expensive, but it's crucial that you have logging enabled when you are engaged in an incident. Without it, you may never be able to determine things like patient zero or the initial infection vector. These failures can be catastrophic if multiple actors are able to abuse that same undiscovered weakness.

Part of this process also involves evaluating your own security posture and risk. This is achieved through a variety of means, but a good start would be to look at red teaming. This can be done by building and growing a red team internally or hiring an external group to provide the same services, but ideally, it should include both. There is value in having the institutional knowledge that comes from having an internal red team, but there is also value in having a different perspective which is something that external groups tend to provide. However, the most important part of the process is actually taking action on these findings. Progress can only be made if the findings are dealt with in a methodical and economic way, which will pay huge dividends down the road.

Organizations should begin moving toward zero-trust now

Nation-states have been focused on abusing trust to achieve their goals, whether it be espionage, destruction, or disruption. At some point, for businesses to succeed, they need to trust other businesses and partners. However, adversaries also seek to exploit this same trust, which often involves access. In some ways, that trust also plays into the recent supply chain attacks.

The concept of zero-trust acknowledges that trust is something earned, but needs to be re-evaluated. In 2022, that doesn't mean yearly, quarterly, or monthly, but continuously each time they connect. One compromise of a trusted partner could be devastating to an organization, even if that organization has market-leading security technologies and a solid security foundation. It's this trust we have repeatedly seen attackers exploit over the last several years, including with SolarWinds, Kaseya and NotPetya.

Organizations need to trust but verify. Just because a vendor states it is best to run the application as admin or exclude it from scanning does not mean that they should be granted without questioning. Securing the software supply chain is difficult enough and less monitoring and permissions controls won't help. For service supply chain attacks, where the whole service is provided on a complete external infrastructure, monitoring is more difficult but still possible and could have helped mitigate attacks like the Sea Turtle.

One of the big advantages of zero-trust is that it also treats internal and external assets with scrutiny. In a world where the attacker may or may not already have a foothold inside the environment or could be an actual employee, having a zero-trust architecture can help you detect and prevent it from becoming a much larger incident. Evaluating the user's posture to determine trust every time they connect can help prevent them from accessing with an infected laptop or one with out-of-date patching and security tools. This type of continuous evaluation of the trustworthiness of users can play a key role in preventing the next big breach.

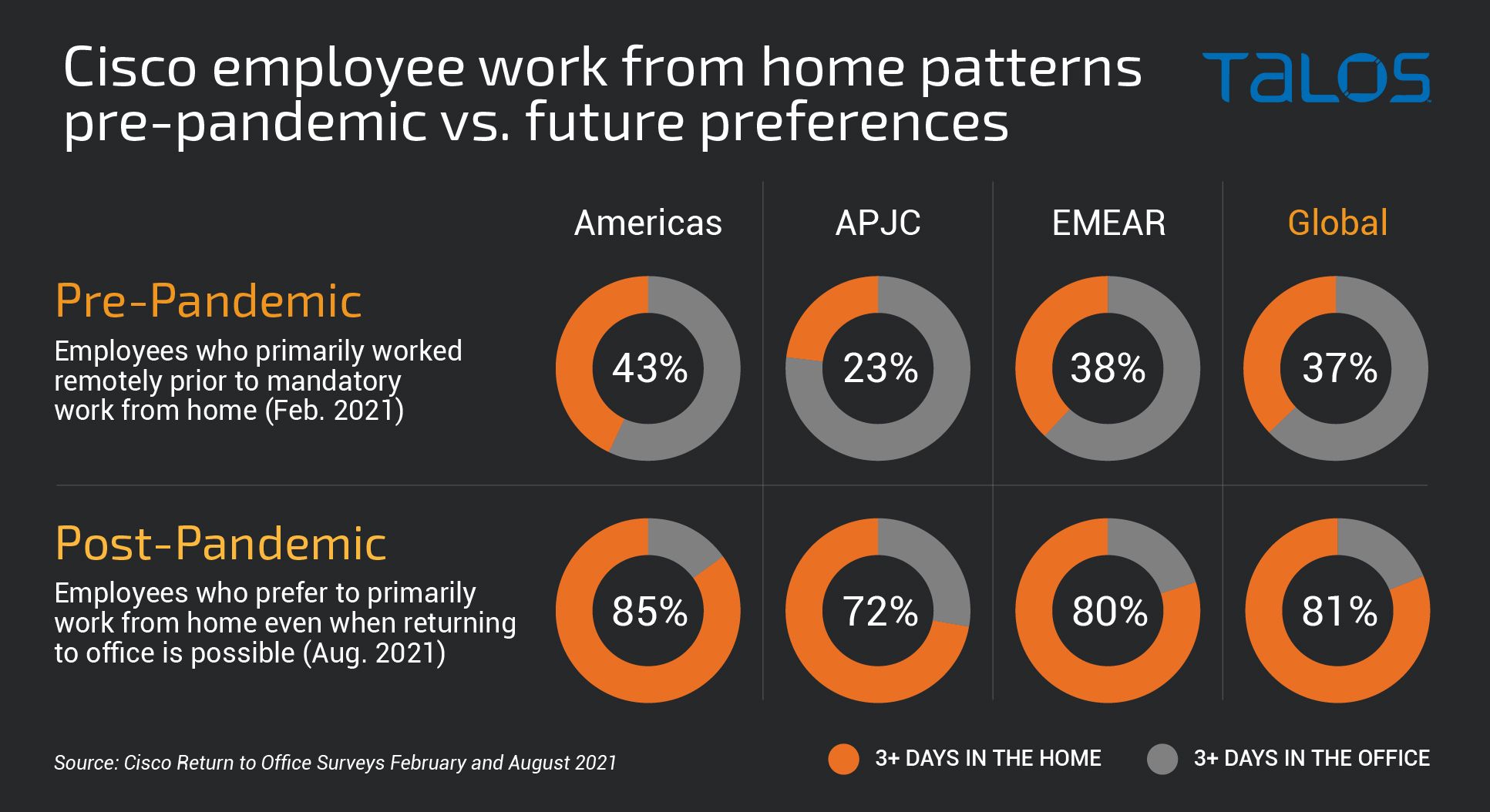

Hybrid work will bring unique challenges along with opportunity

We cannot lose sight as to why this is all happening — companies are switching to a permanent hybrid work model. This alone requires us to think differently as security leaders. In the past, we relied on the protections that physical offices provided, including on-premise security and technology that protects those operating from those friendly confines. However, the hybrid world largely eliminates the office and the employee works from wherever they are and the protections need to follow them. That's where SASE architecture comes into play.

SASE is another important security concept that can protect against attacks. This new framework, introduced by Gartner in 2019, helps secure the ongoing digital transformation of businesses moving to the cloud by consolidating networking and security functions into a single, integrated cloud service. As organizations increasingly adopt and normalize remote work policies, SASE allows organizations to apply secure access no matter where their users, applications or devices are located.

SASE also has the benefit of being far more resilient than relying on on-premise equipment, which was another one of the problems we outlined earlier. As state-sponsored actors take increasingly aggressive actions against targets and infrastructure, the odds of catastrophic failure continue to increase.

We've already covered some of the technologies that are paramount in successfully dealing with a breach, including logging. But organizations should also consider the following questions:

- How does your enterprise handle logging of assets that aren't physically located in an office or connected to a corporate VPN?

- Are you able to have visibility into your XDR solution when the asset isn't bound to your network?

- Should you implement zero trust and evaluate the security posture of a device every time it connects to the network?

Conclusion

If the last few years have taught us anything, it's that we're bad at predicting the future. We went through a decade of mobile threats being the next big thing before we really saw state-sponsored actors increase their activity. What we can see are the trends that have emerged, and there are some concerning indicators. Today, it's not just state-sponsored actors leveraging zero-days and compromising service providers. The APT space is filled with new combatants that haven't spent the last 10 to 20 years learning the hard lessons and building robust capabilities. This has led to more risky behavior than we've seen historically, without as much regard for collateral damage, as evidenced in Sea Turtle's targeting of DNS.

What was once a space reserved for espionage has now broadened its targeting to include dissidents and activists as much as the nations that threaten their borders or interests. These attacks have also included destructive and disruptive elements instead of pure espionage.

Combine that with a criminal enterprise making billions of dollars annually, leveraging a monetization capability that never existed in the past with cryptocurrencies. We've never faced more challenges as defenders, but there are potential solutions. Begin looking at the technologies that are going to make the most impact: implement MFA, start the move toward zero trust, and build the security fundamentals you need to succeed. The next several years are likely to be tough, with the legal and governmental actions necessary to thwart these activities lagging behind. However, the pandemic has forced an unprecedented shift in working behaviors and, with it, new opportunities to reconsider our approach to security.